Life on Mars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crime Drop and the Security Hypothesis

British Society of Criminology Newsletter, No. 64, Special Edition, Autumn 2009 Life on Mars Eugene McLaughlin City University, London Titles of annual academic conferences are intriguing matters. The title of the BSC Cardiff Conference was “A „Mirror‟ or a „Motor‟? What is Criminology for?”. Prospective delegates were asked to deliberate on how they viewed themselves and their work. Should they be providing a „mirror‟ that „seeks to reflect as accurately as possible the conditions that are encountered in the contemporary social order?‟. Or should they have an applied orientation with their research being „a „motor‟ of social change to advance key values of justice and security?‟. Now of course the „either/or‟ nature of the quotes are worthy of a paper in themselves and a plenary session addressing the „what is criminology for?‟ theme directly would have been fascinating. As with every conference, the initial session reflected the organisers‟ struggle to manage the array of interests that define British criminology. The opening of the conference runs to familiar formula of a brief welcome by the President and someone representing the place hosting the event. There would also be an opening plenary paper by an eminent criminologist tasked to, in some way, capture the theme of the conference. In this case it would be Lawrence Sherman seeking to evidence the enlightenment credentials of „Experimental Criminology‟. However, this year‟s opening would also include the BSC‟s new Outstanding Achievement Award. Eventual confirmation that Stan Cohen would be the recipient of the first award added an extra buzz to proceedings. After all, it was Cohen who has described his ambivalent but ongoing relationship with criminology as one of “repressive tolerance”. -

Ebook Download Ashes to Ashes Ebook Free Download

ASHES TO ASHES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tami Hoag | 593 pages | 01 Aug 2000 | Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc | 9780553579604 | English | New York, United States Ashes to Ashes PDF Book Greil Marcus. Save Word. This site uses cookies and other tracking technologies to assist with navigation and your ability to provide feedback, analyse your use of our products and services, assist with our promotional and marketing efforts, and provide content from third parties. Ashes to ashes , funk to funky. See how we rate. Hunt's grass 'Rock Salmon' Doyle is murdered after divulging an upcoming heist, which Alex Steve Silberman and David Shenk. Share reduce something to ashes Post the Definition of reduce something to ashes to Facebook Share the Definition of reduce something to ashes on Twitter. User Reviews. The exploits of Gene Hunt continue in the hit drama series. Gene distrusts two former colleagues claiming to have travelled from Manchester on the hunt for an aged stand-up comedian who has allegedly stolen cash from the Police Widows' Fund. I hope that we find out a lot more about this compelling character in the future. Muse, Odalisque, Handmaiden. While the hard science of memorial diamonds is fascinating—a billion years in a matter of weeks! Creators: Matthew Graham , Ashley Pharoah. Queen: The Complete Works. When a violent burglary occurs at Alex's in-laws' house, she encounters their year-old son Peter - the future father of Molly. Learn More about reduce something to ashes Share reduce something to ashes Post the Definition of reduce something to ashes to Facebook Share the Definition of reduce something to ashes on Twitter Dictionary Entries near reduce something to ashes reducer sleeve reduce someone to silence reduce someone to tears reduce something to ashes reducible polynomial reducing agent reducing coupling. -

Keeley Hawes, Philip Glenister, Dean Andrews, Marshall Lancaster, Montserrat Lombard

Ashes to Ashes (DVD) Talent: Keeley Hawes, Philip Glenister, Dean Andrews, Marshall Lancaster, Montserrat Lombard. Director: Johnny Campbell, Bille Eltringham Classification: M (Mature) Duration: 516 minutes (including 8 episodes) We rate it: Five stars. Date of review: 22nd October, 2009 Several years ago, audiences in both the UK and Australia were introduced to the wondrous BBC drama Life on Mars. Taking its name from a David Bowie song, Life on Mars followed the intriguing exploits of a 2006 Manchester cop, Sam Tyler, (played by the wonderful John Simm) who was hit by a car and seemingly sent back in time to 1973. The show functioned as a compelling psychological thriller, following Tyler’s efforts to discover what had sent him back in time (was he in a coma, dying, dreaming, or in some kind of limbo-land or Purgatory?) and his attempts to escape 1973 and get back to his life in 2006. At the same time, the show was a loving and at times hilarious re-creation of the 1970s British cop-show milieu (think of The Sweeney crossed with The Professionals, but shot with today’s filmmaking technology), and it featured the wonderful Philip Glenister as the now-iconic DCI Gene Hunt, a politically- incorrect, hilariously foul-mouthed and utterly lovable character who infuriated Tyler as often as he helped him in his various quests. Life on Mars was a critical and commercial hit, and it spawned a tremendously effective second series. The characters central to Life on Mars were both sympathetic and fascinating, the writing and direction of the episodes occasionally awe-inspiring, and the mystery at the heart of the entire show was brilliantly handled to the very end. -

A Review of New Historical Drama from the BBC

Eras Edition 9, November 2007 – http://www.arts.monash.edu.au/eras ‘Time-warp Television’ – A review of new historical drama from the BBC: Life on Mars, created by Mathew Graham, Tony Jordan and Ashley Pharoah, BBC, 2006. Robin Hood, created by Foz Allan and Dominic Minghella, BBC, 2006. Torchwood, created by Russell T. Davies, BBC, 2006. Robin Hood in an anorak and touting an anti-war message? Costume drama in the gritty back streets of 1970s Manchester? Clearly this is not your father’s BBC. While there is still plenty of Austen and Dickens for the purist, the BBC, long the home of waistcoats, mutton chops and empire waists, has breathed some new life into the historical drama with two series that seem to engage as much with the way we respond to history as to the historical setting itself. A cult and critical hit, Life on Mars, follows Manchester Police Detective Sam Tyler (played by John Simm) who is ‘transported’ back to 1973 after being hit by a car. Used to being a Detective Chief Inspector with expensive digs, a well-cut suit, and police-work governed by political correctness and computers, Sam finds himself demoted, dressed in a leather jacket, living in a dingy room with a Murphy-bed, and working with DCI Gene Hunt. Hunt, played with joyful relish by Philip Glenister, is the very antithesis of modern policing. He is unabashedly racist, sexist, homophobic and not above bashing the uncooperative suspect mid-interview. All guts and reaction, he is the ying to Sam’s yang, as it becomes clear that DI Tyler has lost the ability to trust his instincts. -

Fantastika Journal

FANTASTIKAJOURNAL After Bowie: Apocalypse, Television and Worlds to Come Andrew Tate Volume 4 Issue 1 - After Fantastika Stable URL: https:/ /fantastikajournal.com/volume-4-issue-1 ISSN: 2514-8915 This issue is published by Fantastika Journal. Website registered in Edmonton, AB, Canada. All our articles are Open Access and free to access immediately from the date of publication. We do not charge our authors any fees for publication or processing, nor do we charge readers to download articles. Fantastika Journal operates under the Creative Commons Licence CC-BY-NC. This allows for the reproduction of articles for non-commercial uses, free of charge, only with the appropriate citation information. All rights belong to the author. Please direct any publication queries to [email protected] www.fantastikajournal.com Fantastika Journal • Volume 4 • Issue 1 • July 2020 AFTER BOWIE: APOCALYPSE, TELEVISION AND WORLDS TO COME Andrew Tate Let’s start with an image or, more accurately, an image of images from a 1976 film. A character called Thomas Jerome Newton is surrounded by the dazzle and blaze of a bank of television screens. He looks vulnerable, overwhelmed and enigmatic. The moment is an oddly perfect metonym of its age, one that speaks uncannily of commercial confusion, artistic innovation and political inertia. The film is Nic Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth – an adaptation of Walter Tevis’ 1963 novel – and the actor on screen is David Bowie, already celebrated for his multiple, mutable pop star identities in his first leading role in a motion picture. In an echo of what Nicholas Pegg has called “the ongoing sci-fi shtick that infuses his most celebrated characters” – including by this time, for example, Major Tom of “Space Oddity” (1969), rock star messiah Ziggy Stardust and the post-apocalyptic protagonists of “Drive-In Saturday” (1972) – he performs the role of an alien (Kindle edition, location 155). -

A2A 3 Ep 8 Shooting Script

1 EXT. PLAYING FIELDS - DAY 0 1 Municipal parkland. * STEWART HALL (V.O.) It was Will Shakespeare who wrote; “We must take the current when it serves or lose our ventures.” You join us here at Fenchurch East Recreation Grounds. The current serves. The venture can not be lost. And - IT’S - A - KNOCKOUT!! Iconic Theme Tune kicks in - A giant FOAM-HEADED ALEX DRAKE sets off across the obstacle course, weaving left and right. STEWART HALL commentates between bouts of laughter. A whistle blows. STEWART HALL (V.O.) (CONT’D) And Alex is off! Hither and yon! Camera WHIP PANS to the other end of the field where MOLLY waits in her school uniform, hollering her support. MOLLY Come on mum! You can do it! Back to FOAM-HEAD ALEX who reaches a huge mountain of paper. STEWART HALL (V.O.) Through the paperwork ... And she’s found something! It’s the numbers 6 - 6 - 20 ... A second whistle blows. STEWART HALL (V.O.) (CONT’D) And that’s the cue for DCI Gene Hunt to go after her! A FOAM-HEAD GENE sets off in wobbly pursuit, closing the gap fast. FOAM-HEAD ALEX stumbles. STEWART HALL (V.O.) (CONT’D) He’s gaining! Gene Hunt is gaining! FOAM-HEAD ALEX is reaching a fence with a weather-vane. Familiar to us - the old man with the knapsack. STEWART HALL (V.O.) (CONT’D) Now she has to get around the weather-vane ... FOAM-HEAD ALEX crashes through the fence. STEWART hoots. (CONTINUED) Ashes 3 - Episode 8 - SHOOTING SCRIPT - 18/12/09 2. -

John Simm ~ 47 Screen Credits and More

John Simm ~ 47 Screen Credits and more The eldest of three children, actor and musician John Ronald Simm was born on 10 July 1970 in Leeds, West Yorkshire and grew up in Nelson, Lancashire. He attended Edge End High School, Nelson followed by Blackpool Drama College at 16 and The Drama Centre, London at 19. He lives in North London with his wife, actress Kate Magowan and their children Ryan, born on 13 August 2001 and Molly, born on 9 February 2007. Simm won the Best Actor award at the Valencia Film Festival for his film debut in Boston Kickout (1995) and has been twice BAFTA nominated (to date) for Life On Mars (2006) and Exile (2011). He supports Man U, is "a Beatles nut" and owns seven guitars. John Simm quotes I think I can be closed in. I can close this outer shell, cut myself off and be quite cold. I can cut other people off if I need to. I don't think I'm angry, though. Maybe my wife would disagree. I love Manchester. I always have, ever since I was a kid, and I go back as much as I can. Manchester's my spiritual home. I've been in London for 22 years now but Manchester's the only other place ... in the country that I could live. You never undertake a project because you think other people will like it - because that way lies madness - but rather because you believe in it. Twitter has restored my faith in humanity. I thought I'd hate it, but while there are lots of knobheads, there are even more lovely people. -

Introduction: Questions of Class in the Contemporary British Novel

Notes Introduction: Questions of Class in the Contemporary British Novel 1. Martin Amis, London Fields (New York: Harmony Books, 1989), 24. 2. The full text of Tony Blair’s 1999 speech can be found at http://news.bbc. co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/politics/460009.stm (accessed on December 9, 2008). 3. Terry Eagleton, After Theory (New York: Perseus Books, 2003), 16. 4. Ibid. 5. Peter Hitchcock, “ ‘They Must Be Represented’: Problems in Theories of Working-Class Representation,” PMLA Special Topic: Rereading Class 115 no. 1 January (2000): 20. Savage, Bagnall, and Longhurst have also pointed out that “Over the past twenty-five years, this sense that the working class ‘matters’ has ebbed. It is now difficult to detect sustained research interest in the nature of working class culture” (97). 6. Gary Day, Class (London and New York: Routledge, 2001), 202. This point is also echoed by Ebert and Zavarzadeh: “By advancing singularity, hetero- geneity, anti-totality, and supplementarity, for instance, deconstruction has, among other things, demolished ‘history’ itself as an articulation of class relations. In doing so, it has constructed a cognitive environment in which the economic interests of capital are seen as natural and not the effect of a particular historical situation. Deconstruction continues to produce some of the most effective discourses to normalize capitalism and contribute to the construction of a capitalist-friendly cultural common sense . .” (8). 7. Slavoj Žižek, In Defence of Lost Causes (London and New York: Verso, 2008), 404–405 (Hereafter, Lost Causes). 8. Andrew Milner, Class (London: Sage, 1999), 9. 9. Gavin Keulks, ed., Martin Amis: Postmodernism and Beyond (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 73. -

Lesley Sharp and the Alternative Geographies of Northern English Stardom

This is a repository copy of Lesley sharp and the alternative geographies of northern english stardom. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/95675/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Forrest, D. and Johnson, B. (2016) Lesley sharp and the alternative geographies of northern english stardom. Journal of Popular Television, 4 (2). pp. 199-212. ISSN 2046-9861 https://doi.org/10.1386/jptv.4.2.199_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Lesley Sharp and the alternative geographies of Northern English Stardom David Forrest, University of Sheffield Beth Johnson, University of Leeds Abstract Historically, ‘North’ (of England) is a byword for narratives of economic depression, post-industrialism and bleak and claustrophobic representations of space and landscape. -

Life on Mars

Appendix 2 Life on Mars 722 Life on Mars Translation strategies Loan Official translation Calque Hypernym Hyponym Explicitation Substitution Lexical recreation Compensation Elimination Creative addition 723 LIFE ON MARS Season 1 Episode 1 (Pilot) 1/1 ORIGINAL FILM DIALOGUE 13.47-13.53 SAM: Who the hell are you? GENE: Gene Hunt, your DCI, and it's 1973. Almost dinner time. I'm 'avin' 'oops. ITALIAN ADAPTATION BACK-TRANSLATION SAM: Chi sei tu? SAM: Who are you? GENE: Gene Hunt, il tuo ispettore capo. E’ GENE: Gene Hunt, your chief inspector. il 1973, ora di cena. E muoio dalla fame. It’s 1973, dinner time. And I’m starving. 1/2 ORIGINAL FILM DIALOGUE 14.21-14.33 OPERATOR: Operator. SAM: No, I want a mobile number. OPERATOR: What? SAM: A mobile number. 0770 813- OPERATOR: Is that an international number? SAM: No, it… I....I need you to connect me to a Virgin... number. Virgin mobile. OPERATOR: Don't you start that sexy business with me, young man. I can trace this call. ITALIAN ADAPTATION BACK-TRANSLATION CENTRALINISTA: Centralino. OPERATOR: Operator. SAM: Senta. Vorrei il numero di un SAM: Listen. I would like to have the cellulare. number of a mobile. CENTRALINO: Cosa? OPERATOR: What? SAM: Il numero di un cellulare. 0770 813… SAM: The number of a mobile. 0770 813… CENTRALINO: E’ un numero OPERATOR: Is it an international number internazionale forse? perhaps? SAM: No. Io ho bisogno che lei mi metta in SAM: No. I need you to connect me to a contatto con un numero di… un cellulare, mobile… number, a mobile phone. -

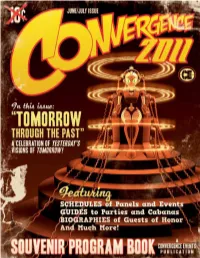

Souvenir & Program Book (PDF)

THAT STATEMENT CONNECTS the modern Steam Punk Movement, The Jetsons, Metropolis, Disney's Tomorrowland, and the other items that we are celebrating this weekend. Some of those past futures were unpleasant: the Days of Future Past of the X-Men are a shadow of a future that the adult Kate Pryde wanted to avoid when she went back to the present day of the early 1980s. Others set goals and dreams; the original Star Trek gave us the dreams and goals of a bright and shiny future t h a t h a v e i n s p i r e d generations of scientists and engineers. Robert Heinlein took us to the Past through Tomorrow in his Future History series, and Asimov's Foundation built planet-wide cities and we collect these elements of the past for the future. We love the fashion of the Steampunk movement; and every year someone is still asking for their long-promised jet pack. We take the ancient myths of the past and reinterpret them for the present and the future, both proving and making them still relevant today. Science Fiction and Fantasy fandom is both nostalgic and forward-looking, and the whole contradictory nature is in this year's theme. Many of the years that previous generations of writers looked forward to happened years ago; 1984, 1999, 2001, even 2010. The assumptions of those time periods are perhaps out-of-date; technology and society have passed those stories by, but there are elements that still speak to us today. It is said that the Golden Age of Science Fiction is when you are 13. -

Our Side of the Mirror: the (Re)

inolo rim gy C : d O n p a e n y King, Social Crimonol 2013, 1:1 g A o c l c o i e c s DOI: 10.4172/2375-4435.1000104 s o Sociology and Criminology-Open Access S ISSN: 2375-4435 ReviewResearch Article Article OpenOpen Access Access Our Side of the Mirror: The (Re)-Construction of 1970s’ Masculinity in David Peace’s Red Riding Martin King1* and Ian Cummins2 1Department of Social Work and Social Change, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK 2Department of Social Work-University of Salford, UK Abstract David Peace and the late Gordon Burn are two British novelists who have used a mixture of fact and fiction in their works to explore the nature of fame, celebrity and the media representations of individuals caught up in events, including investigations into notorious murders. Both Peace and Burn have analysed the case of Peter Sutcliffe, who was found guilty in 1981 of the brutal murders of thirteen women in the North of England. Peace’s novels filmed as the Red Riding Trilogy are an excoriating portrayal of the failings of misogynist and corrupt police officers, which allowed Sutcliffe to escape arrest. Burn’s somebody’s Husband Somebody’ Son is a detailed factual portrait of the community where Sutcliffe spent his life. Peace’s technique combines reportage, stream of consciousness and changing points of views including the police and the victims to produce an episodic non linear narrative. The result has been termed Yorkshire noir. The overall effect is to render the paranoia and fear these crimes created against a backdrop of the late 1970s and early 1980s.