@ in Partial Fulfillment Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GENERAL AGREEMENT on Ï^^We TARIFFS and TRADE Limited Distribution

RESTRICTED GENERAL AGREEMENT ON ï^^we TARIFFS AND TRADE Limited Distribution '--•••-•• ••-•- Originals English NOTIFICATIONS OF IMPORT RESTRICTIONS OF NEWLY INDEPENDENT COUNTRIES Addendum BARBADOS The Government of Barbados has submitted the following information concerning import restrictions in force in Barbados up to 30 September 1968. 1. The information attached shows the goods which are subject to import restrictions and details concerning the application of such restrictions. 2. The Government of Barbados permits entry on open general licence for all goods, other than those set out in the Second Schedule of the Exports and Imports (General Open Import Licence) Order 1962 as amended by the Exports and Imports (General Open Import Licence) (Amendment) (No.2) Order 1968, from all countries of the world except those listed in the First Schedule of the 1962 Order. 3. It should be noted that no discrimination exists in relation to trade with Japan. In view of the non-reciprocity of trade with that country, it has been decided that the quantity and value of imports should be kept under constant review in order not to widen an already adverse imbalance of trade with that country and to protect certain local infant industries. 4. Trade with socialist countries is not prohibited. In order, however, that control can be exercised on trade relations with these countries the Government considers it necessary to licence imports. 5. Because of South Africa's apartheid policy and the illegal régime which has been established in Southern Rhodesia,.trade with these two countries has been prohibited. 6. Detailed information concerning the applicable.import régime and.the reason for restriction concerning items mentioned in the export and import, order s following are__co.ntain.ed in .the. -

Observations with AGF Task Forces Frigid and Williwaw

MEDICAL DEPARTMENT FIELD RESEARCH LABORATORY Fort Knox, Kentucky PROJECT NO. 6-64-12-02 M.D.F.R.L. NO. 6-64-12-02-(2) Submitted 12 January 194S OBSERVATIONS WITH AGF TASK FORCES FRIGID AND WHUWAFf under Cold, Study of Physiological Effects of. Approved 25 September 1942. MDFRL Project No, 6-64-12-02-(2)• OBSERVATIONS .71TH A OF TASK FORCES FRIGID AND AILLIWAW by G. Molnar, Physiologist, R. B. Magee, Capt., M.C, and 3. L, Durrum, Capt., M.C. from Medical Department Field Research Laboratory Fort Knox, Kentucky 12 January 194S under Cold, Study of Physiological effects of. Approved 25 September 1942. IDFRL Project No. 6-64-12-02-(2). Project No, B-6-64-12-02 Sub-project IDFRL 02-2 MEDEA 12 January 1943 ABSTRACT OBSERVATIONS tfITH AGF TASK FORCES FRIGID AND WILLIWAH OBJECT During the winter of 1946-1947 three observers from this laboratory conducted physiological observations on troops in the field at Task Force Frigid and Task Force Williwaw, and also on Eskimos at Barrow, Alaska. To enhance the value of cursory visual' impressions, special tests under controlled conditions were performed. Information was obtained concerning problems of water balance and endurance, and also concerning the body tem- perature responses of Eskimos as compared with those of white men. RESULTS 1. Pure-breed Eskimos maintained warmer finger temperatures than white men during the first 1 to 3 hours of exposure to outdoor weather under identical conditions. These results suggest values to look for in the preselection of men for arctic duty and in the assessment of acclimati- zation changes. -

HOUSE BILL NO. 1268 of North Dakota

90183.0100 Sixty-first Legislative Assembly HOUSE BILL NO. 1268 of North Dakota Introduced by Representatives Belter, Boehning Senator Fischer 1 A BILL for an Act to create and enact a new section to chapter 57-39.2 of the North Dakota 2 Century Code, relating to a sales and use tax exemption for clothing; and to provide an effective 3 date. 4 BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF NORTH DAKOTA: 5 SECTION 1. A new section to chapter 57-39.2 of the North Dakota Century Code is 6 created and enacted as follows: 7 Sales tax exemption for clothing. Gross receipts from sales of clothing are exempt 8 from taxes imposed under this chapter. For purposes of this section, "clothing" means all 9 human wearing apparel suitable for general use. For purposes of this section: 10 1. "Clothing" includes: 11 a. Aprons, household and shop; 12 b. Athletic supporters; 13 c. Baby receiving blankets; 14 d. Bathing suits and caps; 15 e. Beach capes and coats; 16 f. Belts and suspenders; 17 g. Boots; 18 h. Coats and jackets; 19 i. Costumes; 20 j. Diapers, children and adult, including disposable diapers; 21 k. Ear muffs; 22 l. Footlets; 23 m. Formal wear; 24 n. Garters and garter belts; Page No. 1 90183.0100 Sixty-first Legislative Assembly 1 o. Girdles; 2 p. Gloves and mittens for general use; 3 q. Hats and caps; 4 r. Hosiery; 5 s. Insoles for shoes; 6 t. Laboratory coats; 7 u. Neckties; 8 v. Overshoes; 9 w. Panty hose; 10 x. -

Pattern Changing Clothing

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 4-17-2013 Pattern changing clothing Yong Kwon Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Kwon, Yong, "Pattern changing clothing" (2013). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. April 17 Pattern Changing Clothing 2013 Author – Yong hwan Kwon Degree – Master of Fine Arts Program – Industrial Design Rochester Institute of Technology College of Imaging Arts & Sciences Pattern Changing Clothing by yong hwan Kwon Approvals Stan Rickel, Chief Advisor & Committee Member Associate Professor, Graduate Program Chair, Industrial Design Signature: Date: Marla K Schweppe, Associate Advisor & Committee Member Professor, Computer Graphic Design Signature: Date: W. Michelle Harris, Associate Advisor & Committee Member Associate Professor, Interactive Game & Media Signature: Date: 1 Table of Contents Abstract 5 01 Introduction 6 02 Design Background 8 - The History of Textile Technology - The History of Modern fashion - Fashioning Technology - Fashioning Technology - Considerations - Futuristic Clothing 03 Design Motivation 18 - Individuality in Fashion - Expressive Ways of individuality - Mass Customization 04 Problems of Current Clothing 25 - Irrational Consumption of Clothing - Waste of Natural -

TB-ST-530:(3/14):Lists of Exempt and Taxable Clothing, Footwear, and Items Used to Make Or Repair Exempt Clothing:Tbst530

Tax Bulletin Sales and Use Tax TB-ST-530 March 10, 2014 Lists of Exempt and Taxable Clothing, Footwear, and Items Used to Make or Repair Exempt Clothing Clothing, footwear, and items used to make or repair exempt clothing sold for less than $110 per item or pair are exempt from the New York State 4% sales tax, the local tax in localities that provide the exemption, and the ⅜% Metropolitan Commuter Transportation District (MCTD) tax within exempt localities in the MCTD. See Publication 718-C, Sales and Use Tax Rates on Clothing and Footwear, for: • a listing of local jurisdictions that provide the exemption; and • a listing of local jurisdictions that do not provide the exemption, along with their applicable tax rates. The following charts list examples of exempt and taxable clothing, footwear, and items used to make or repair exempt clothing. Exempt items Aerobic clothing Formal clothing (unless rented) Shawls and wraps Antique clothing (for wear) Fur clothing Shirts Aprons Garters/garter belts Shoes (ballet, bicycle, bowling, Arm warmers Girdles cleated, football, golf, Athletic supporters Gloves (batting, bicycle, dress jazz/dance, soccer, track, Athletic or sport uniforms or [unless rented], garden, golf, etc.) clothing (but not equipment ski, tennis, work) Shoe inserts such as mitts, helmets and Graduation caps and gowns Shoe laces pads) (unless rented) Shoulder pads for dresses, Bandannas Gym suits jackets, etc. (but not athletic Bathing caps Hand muffs or sport protective pads) Bathing suits Handkerchiefs Shower caps Beach caps -

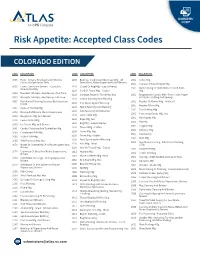

CO Class Code List (PDF)

WORKERS’ COMP Risk Appetite: Accepted Class Codes COLORADO EDITION CODE DESCRIPTION CODE DESCRIPTION CODE DESCRIPTION 0005 Farm--Nursery Employees And Drivers - 2157 Bottling--Carbonated Beverage Mfg.--All 2501 Collar Mfg. Cannabis Operations Only Operations, Route Supervisors, And Drivers 2501 Cushion, Pillow Or Quilt Mfg. 0035 Farm--Florist And Drivers - Cannabis 2220 Carpet Or Rug Mfg.--Jute Or Hemp Operations Only 2501 Doll Clothing Or Cloth Dolls Or Cloth Parts 2220 Cord Or Twine Mfg.--Cotton Mfg. 0908 Domestic Workers--Residences--Part-Time 2220 Cordage, Rope Or Twine Mfg. Noc 2501 Draperies Or Curtain Mfg.--From Cloth, Paper 0913 Domestic Workers--Residences-Full-Time Or Plastic--Cutting And Sewing 2220 Cotton Spinning And Weaving 0917 Residential Cleaning Services By Contractor-- 2501 Feather Or Flower Mfg.--Artificial Inside 2220 Flax Spinning And Weaving 2501 Feather Pillow Mfg. 2002 Pasta Or Noddle Mfg. 2220 Hemp Spinning And Weaving 2501 Fur Clothing Mfg. 2003 Bakery And Drivers, Route Supervisors 2220 Jute Spinning And Weaving 2501 Furnishing Goods Mfg. Noc 2003 Doughnut--Mfg. And Drivers 2220 Linen Cloth Mfg. 2501 Hair Goods Mfg. 2016 Cereal Or Bar Mfg. 2220 Rope Mfg. Noc 2501 Hat Mfg. 2039 Ice Cream Mfg. And Drivers 2220 Rug Mfg.--Jute Or Hemp 2501 Lingerie Mfg. 2041 Candy, Chocolate And Confection Mfg. 2220 Thread Mfg.--Cotton 2501 Millinery Mfg. 2065 Condensed Milk Mfg. 2220 Twine Mfg. Noc 2501 Sailmaking 2065 Malted Milk Mfg. 2220 Twine Mfg.--Cotton 2501 Shirt Mfg. 2065 Milk Products Mfg. Noc 2220 Wool Spinning And Weaving 2501 Sign Manufacturing--Silk-Screen Printing-- 2070 Butter Or Cheese Mfg. -

Hanging Standards 1 | Page

UPDATED JULY 20, 2021 SECTION 1 HANGER REQUIREMENTS .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Nordstrom & Rack Stores Hanger Requirements .......................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Ecommerce & Reserve Stock Hanger Requirements .................................................................................................................................................................... 4 NORDSTROM Hanging Standards 1 | Page SECTION 1 HANGER REQUIREMENTS Nordstrom requires specific product types to be shipped on hangers. Hangers must be inserted into these products and shipped in cartons. Expense Offset Fees will be incurred if product received with hangers has size indictors, supplier logo/stickers, full foam covers, foam mini covers, loose foam, or fabric swatches. Questions regarding hanger requirements can be directed to the Nordstrom Floor Ready Department by emailing [email protected]. Additional Specifications • Use a combination of top and bottom hangers for all 2-piece coordinates/sets • Rubberized grippers required (style PGRAB) on some items to prevent damage or slippage (i.e. scoop neck tops, fine gauge knits, etc.) • Bottoms must be hung at the waist Unacceptable Items • Size indicators and supplier logos/stickers on hangers • Full foam covers on top hangers or -

Fur Dress, Art, and Class Identity in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England and Holland by Elizabeth Mcfadden a Dissertatio

Fur Dress, Art, and Class Identity in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England and Holland By Elizabeth McFadden A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art and the Designated Emphasis in Dutch Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Elizabeth Honig, Chair Professor Todd Olson Professor Margaretta Lovell Professor Jeroen Dewulf Fall 2019 Abstract Fur Dress, Art, and Class Identity in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England and Holland by Elizabeth McFadden Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art Designated Emphasis in Dutch Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Elizabeth Honig, Chair My dissertation examines painted representations of fur clothing in early modern England and the Netherlands. Looking at portraits of elites and urban professionals from 1509 to 1670, I argue that fur dress played a fundamentally important role in actively remaking the image of middle- class and noble subjects. While demonstrating that fur was important to establishing male authority in court culture, my project shows that, by the late sixteenth century, the iconographic status and fashionability of fur garments were changing, rendering furs less central to elite displays of magnificence and more apt to bourgeois demonstrations of virtue and gravitas. This project explores the changing meanings of fur dress as it moved over the bodies of different social groups, male and female, European and non-European. My project deploys methods from several disciplines to discuss how fur’s shifting status was related to emerging technologies in art and fashion, new concepts of luxury, and contemporary knowledge in medicine and health. -

Fashion,Costume,And Culture

FCC_TP_V3_930 3/5/04 3:57 PM Page 1 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages FCC_TP_V3_930 3/5/04 3:57 PM Page 3 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Volume 3: European Culture from the Renaissance to the Modern3 Era SARA PENDERGAST AND TOM PENDERGAST SARAH HERMSEN, Project Editor Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast Project Editor Imaging and Multimedia Composition Sarah Hermsen Dean Dauphinais, Dave Oblender Evi Seoud Editorial Product Design Manufacturing Lawrence W. Baker Kate Scheible Rita Wimberley Permissions Shalice Shah-Caldwell, Ann Taylor ©2004 by U•X•L. U•X•L is an imprint of For permission to use material from Picture Archive/CORBIS, the Library of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of this product, submit your request via Congress, AP/Wide World Photos; large Thomson Learning, Inc. the Web at http://www.gale-edit.com/ photo, Public Domain. Volume 4, from permissions, or you may download our top to bottom, © Austrian Archives/ U•X•L® is a registered trademark used Permissions Request form and submit CORBIS, AP/Wide World Photos, © Kelly herein under license. Thomson your request by fax or mail to: A. Quin; large photo, AP/Wide World Learning™ is a trademark used herein Permissions Department Photos. Volume 5, from top to bottom, under license. The Gale Group, Inc. Susan D. Rock, AP/Wide World Photos, 27500 Drake Rd. © Ken Settle; large photo, AP/Wide For more information, contact: Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 World Photos. -

Fur Clothing Retail Gross Receipts Tax Instructions

Fur Clothing Retail Gross Receipts Tax and Use Tax Repealed Effective January 1, 2009 P.L. 2008, c.123, repealed the Fur Clothing Retail Gross Receipts Tax and Use Tax effective January 1, 2009. The final return for the quarter ending December 31, 2008, is due January 20, 2009. Beginning January 1, 2009, sales of fur clothing are subject to sales tax at the rate of 7%. For more information see the Notice to Fur Clothing Sellers Effective January 1, 2009. Continue to next page to view this document. Business Paperless Telefiling System Instructions New Jersey Fur Clothing Retail Gross Receipts Tax (Form FUR-100 Quarterly Return) Filing by Phone When to File Complete the FUR-100 Worksheet, call the Business Paper- Taxpayers subject to the tax must file a quarterly Fur Clothing less Telefiling System at 1-877-829-2866, and select “7” from Retail Gross Receipts Tax Return, Form FUR-100, and remit the menu for the Fur Clothing Retail Gross Receipts Tax Fil- any tax due, on or before the 20th day of month following the ing System. You will be prompted to enter the information end of the calendar quarter. from your worksheet on your Touch-tone telephone keypad. (NOTE: For best results, do not use a cordless or cellular Quarter Ending Due Date phone or one with a keypad in the handset.) The system pro- Jan.-Feb.-Mar. March 31 April 20 vides step-by-step instructions and repeats your entries to Apr.-May-June June 30 July 20 ensure accuracy. When your return is accepted, you will be July-Aug.-Sept. -

May 16, 2011 Federal Trade Commission Office of the Secretary

May 16, 2011 Federal Trade Commission Office of the Secretary, Room H–113 (Annex O) 600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20580 RE: Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking under the Fur Products Labeling Act; Matter No. P074201 On behalf of the more than 11 million members and supporters of The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), I submit the following comments to be considered regarding the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) advance notice of proposed rulemaking under the federal Fur Products Labeling Act (FPLA), 16 U.S.C. § 69, et seq. The rulemaking is being proposed in response to the Truth in Fur Labeling Act (TFLA), Public Law 111–113, enacted in December 2010, which eliminates the de minimis value exemption from the FPLA, 16 U.S.C. § 69(d), and directs the FTC to initiate a review of the Fur Products Name Guide, 16 C.F.R. 301.0. Thus, the FTC indicated in its notice that it is specifically seeking comment on the Name Guide, though the agency is also generally seeking comment on its fur rules in their entirety. As discussed below, the HSUS believes that there is a continuing need for the fur rules and for more active enforcement of these rules by the FTC. The purpose of the FPLA and the fur rules is to ensure that consumers receive truthful and accurate information about the fur content of the products they are purchasing. Unfortunately, sales of unlabeled and mislabeled fur garments, and inaccurate or misleading advertising of fur garments, remain all too common occurrences in today’s marketplace. -

Clothing 105

www.taxes.state.mn.us Clothing 105 Fact Sheet Sales Tax Fact Sheet 105 Clothing is exempt from Minnesota sales and use tax. Clothing means all human wearing apparel suitable for general use. The exemption for clothing does not apply to fur clothing, clothing accessories or equipment, sports or recreational equip- ment, and protective equipment, which are taxable. Examples of nontaxable clothing for general use aprons (household and coveralls, work uniforms, incontinent briefs and snowmobile suits and shop) work clothes, etc. inserts boots athletic supporters dancing costumes insoles for shoes slippers baby receiving blankets diaper inserts jackets and coats sneakers bandanas diapers (cloth and dis- karate uniforms sun visors bath robes posable, baby or adult) lab coats sweat bands and arm beach capes and coats disposable clothing for leotards and tights bands belts general use mittens sweat shirts and sweat suits bibs ear muffs name patches or em- socks and stockings blaze orange jackets and footlets blems sold attached to steel toe shoes and boots pants formal apparel clothing boots garters and garter belts neckties suspenders bowling shirts and shoes girdles overshoes swim suits and caps bridal apparel gloves for general use pantyhose tennis shoes camouflage jackets and (cloth, leather, canvas, rainwear (ponchos, jack- T-shirts and jerseys pants latex, vinyl, etc.) ets, shirts and pants) tuxedos caps and hats (ski, hunt- gym suits and shorts rubber pants undergarments ing, fishing, golf, hats sandals uniforms (athletic and baseball) hosiery scarves nonathletic) costumes hospital scrubs shoes and shoe laces wedding apparel hunting jackets and pants shower caps Examples of taxable clothing accessories or equipment Clothing accessories or equipment means incidental items worn on the person or in conjunction with clothing.