Gurgaon and Haryana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Wise Skill Gap Study for the State of Haryana.Pdf

District wise skill gap study for the State of Haryana Contents 1 Report Structure 4 2 Acknowledgement 5 3 Study Objectives 6 4 Approach and Methodology 7 5 Growth of Human Capital in Haryana 16 6 Labour Force Distribution in the State 45 7 Estimated labour force composition in 2017 & 2022 48 8 Migration Situation in the State 51 9 Incremental Manpower Requirements 53 10 Human Resource Development 61 11 Skill Training through Government Endowments 69 12 Estimated Training Capacity Gap in Haryana 71 13 Youth Aspirations in Haryana 74 14 Institutional Challenges in Skill Development 78 15 Workforce Related Issues faced by the industry 80 16 Institutional Recommendations for Skill Development in the State 81 17 District Wise Skill Gap Assessment 87 17.1. Skill Gap Assessment of Ambala District 87 17.2. Skill Gap Assessment of Bhiwani District 101 17.3. Skill Gap Assessment of Fatehabad District 115 17.4. Skill Gap Assessment of Faridabad District 129 2 17.5. Skill Gap Assessment of Gurgaon District 143 17.6. Skill Gap Assessment of Hisar District 158 17.7. Skill Gap Assessment of Jhajjar District 172 17.8. Skill Gap Assessment of Jind District 186 17.9. Skill Gap Assessment of Kaithal District 199 17.10. Skill Gap Assessment of Karnal District 213 17.11. Skill Gap Assessment of Kurukshetra District 227 17.12. Skill Gap Assessment of Mahendragarh District 242 17.13. Skill Gap Assessment of Mewat District 255 17.14. Skill Gap Assessment of Palwal District 268 17.15. Skill Gap Assessment of Panchkula District 280 17.16. -

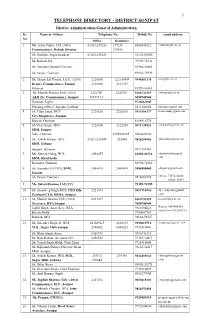

1 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY - DISTRICT SONIPAT District Administration/General Administration Sr

1 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY - DISTRICT SONIPAT District Administration/General Administration Sr. Name of Officer Telephone No. Mobile No. email address No. Office Residence 1. Ms. Anita Yadav, IAS (2004) 01262-255253 279233 8800540222 [email protected] Commissioner, Rohtak Division 274555 Sh. Gulshan, Superintendent 01262-255253 94163-80900 Sh. Rakesh, PA 99925-72241 Sh. Surender, Reader/Commnr. 98964-28485 Sh. Sanjay, Gunman 89010-19999 2. Sh. Shyam Lal Poonia, I.A.S., (2010) 2220500 2221500-F 9996801370 [email protected] Deputy Commissioner, Sonipat 2220006 2221255 Gunman 83959-00363 3. Sh. Munish Sharma, IAS, (2014) 2222700 2220701 8368733455 [email protected] Addl. Dy. Commissioner, Sonipat 2222701,2 9650746944 Gunman, Jagbir 9728661005 Planning Officer, Joginder Lathwal 9813303608 [email protected] 4. Sh. Uday Singh, HCS 2220638 2220538 9315304377 [email protected] City Magistrate, Sonipat Rakesh, Gunman 8168916374 5. Sh .Vijay Singh, HCS 2222100 2222300 9671738833 [email protected] SDM, Sonipat Inder, Gunman 8395900365 9466821680 6. Sh. Ashish Kumar, HCS, 01263-252049 252050 9416288843 [email protected] SDM, Gohana Sanjeev, Gunman 9813759163 7. Ms. Shweta Suhag, HCS, 2584055 82850-00716 sdmkharkhoda@gmail. SDM, Kharkhoda com Ravinder, Gunman 80594-76260 8. Sh . Surender Pal, HCS, SDM, 2460810 2460800 9888885445 [email protected] Ganaur Sh. Pawan, Gunman 9518662328 Driver- 73572-04014 81688-19475 9. Ms. Saloni Sharma, IAS (UT) 78389-90155 10. Sh. Amardeep Singh, HCS, CEO Zila 2221443 9811710744 dy.ceo.zp.snp@gmail. Parishad CEO, DRDA, Sonipat com 11. Sh. Munish Sharma, IAS, (2014) 2221937 8368733455 [email protected] Secretary, RTA Sonipat 9650746944 Jagbir Singh, Asstt. Secy. RTA 9463590022 Rakesh-9467446388 Satbir Dvr-9812850796 Rajesh Malik 7700007784 Ramesh, MVI 94668-58527 12. -

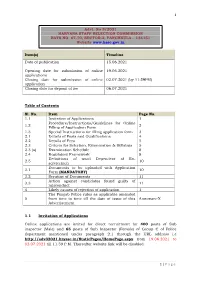

1 1 | Page Item(S) Timeline Date Of

1 Advt. No 3/2021 HARYANA STAFF SELECTION COMMISSION BAYS NO. 67-70, SECTOR-2, PANCHKULA – 134151 Website www.hssc.gov.in Item(s) Timeline Date of publication 15.06.2021 Opening date for submission of online 19.06.2021 applications Closing date for submission of online 02.07.2021 (by 11:59PM) application Closing date for deposit of fee 06.07.2021 Table of Contents Sl. No. Item Page No. 1.1 Invitation of Applications 1 Procedure/Instructions/Guidelines for Online 1.2 2 Filling of Application Form 1.3 Special Instructions for filling application form 3 2.1 Details of Posts and Qualifications 4 2.2 Details of Fees 5 2.3 Criteria for Selection, Examination & Syllabus 5 2.3 (a) Examination Schedule 8 2.4 Regulatory Framework 8 Definitions of word Dependent of Ex- 2.5 10 servicemen Documents to be uploaded with Application 3.1 10 Form (MANDATORY) 3.2 Scrutiny of Documents 11 Action against candidates found guilty of 3.3 11 misconduct 4 Likely causes of rejection of application 1 The Punjab Police rules as applicable amended 5 from time to time till the date of issue of this Annexure-X Advertisement 1.1 Invitation of Applications Online applications are invited for direct recruitment for 400 posts of Sub inspector (Male) and 65 posts of Sub Inspector (Female) of Group C of Police department mentioned under paragraph 2.1 through the URL address i.e http://adv32021.hryssc.in/StaticPages/HomePage.aspx from 19.06.2021 to 02.07.2021 till 11.59 P.M. -

Making Gurgaon the Next Silicon Valley Over the Last Two Decades, Gurgaon Has Emerged As One of Top Locations for IT-BPM Companies Not Only in India but Globally

Making Gurgaon The Next Silicon Valley Over the last two decades, Gurgaon has emerged as one of top locations for IT-BPM companies not only in India but globally. It is home to not only various MNC’s (including many Fortune 500 companies) and large Indian companies but also many SMEs. Growth of the IT/BPM industry has been one of the key drivers behind the development of Gurgaon and its emergence as the “Millennium City”. i) Gurgaon houses about 450 IT-BPM companies employing close to 3.0 lakh professionals directly and 9 lakh indirectly. ii) 76% of employees from Indian IT-BPM industry are < 30 years of age; women constitute 31% of the workforce of which 45% are fresh intakes from campus. Similar trends apply to Gurgaon. iii) Gurgaon contributes 7-8% of Haryana’s State GDP. iv) 10-12% of total Indian IT-BPM employees work out of Gurgaon. v) Gurgaon contributes to a total of about 7% of Indian IT-BPM exports. Clearly, Gurgaon and IT/BPM industry has been a great partnership. They have grown together and contributed to each other’s development. However, in the last few years we have noticed stagnation and even a dip in Gurgaon’s contribution to the Indian IT/BPM industry. While in absolute terms the revenues from the city may still be increasing, clearly in relative terms there is a downfall in the overall contribution. Data shows that not as many companies are setting up centres in Gurgaon as was the case 5 years back. Many state governments have recognized IT-BPM industry as an imperative source of mass employment and economic development empowering large sections of societies and are taking measures to attract the industry. -

Covid-19 Testing Bulletin

COVID-19 TESTING BULLETIN (Govt/Govt-aided Medical Colleges and Hospitals) Status as on 17/04/2021 (09:00 AM) Distt Distt Command Distt Civil Molecular Distt BPS ESIC THSTI KCG ICAR Civil Civil SHKM Civil Molecular Civil PGIMS MAMC Hospital, Molecular Hospital Lab Molecular Samples Khanpur Faridab Farida MC NRCE Hospital Hospital, MC Hospital Lab, Hospital Total Rohtak Agroha Chandi Lab Guru Yamuna Lab, Sonepat ad bad Karnal Hisar Sirsa Panchkula Nuh Rewari Uchana Panipat Mandir Ambala gram nagar Bhiwani Jind Tests done during 2273 1970 1043 224 2056 905 1296 976 174 1935 1732 1980 1969 1295 497 703 1259 1068 23355 last 24 hrs Tests found 824 324 227 76 478 149 260 177 14 317 218 126 523 174 263 136 270 223 4779 Positive Total Tests 532017 478698 164981 100918 376091 179209 467234 199679 40892 204112 274142 349450 304665 106189 124369 127792 138305 94493 4263236 done till date Total Positive 27975 22467 14944 7456 18605 7411 19730 6216 3726 16187 20673 9350 18671 5208 4755 3839 5456 1484 214153 till date Test methodology: Real time PCR *Test methodology: CBNAAT at ESIC, Faridabad, District molecular lab, Ambala, SHKMMC, Nuh and MAMC, Agroha also. TruNat at CH, Sirsa For any details/clarification, please contact on following contact details: 1. PGIMS, Rohtak: Mr Tanuj Gupta: 9611008596 (email: [email protected]) 2. BPS Khanpur: Dr Sandeep: 7027705001 (email: [email protected]) 3. ESIC Faridabad: Dr Aparna Pandey: 9752541322 (email: [email protected]) 4. KCGMC, Karnal: Dr Bhawna Sharma: 9466883708 (email: [email protected]) 5. ICAR-NRCE, Hisar: Dr Baldev Gulati: 9416650040 (email: [email protected]) 6. -

Directory of Officers Office of Director of Income Tax (Inv.) Chandigarh Sr

Directory of Officers Office of Director of Income Tax (Inv.) Chandigarh Sr. No. Name of the Officer Designation Office Address Contact Details (Sh./Smt./Ms/) 1 P.S. Puniha DIT (Inv.) Room No. - 201, 0172-2582408, Mob - 9463999320 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2587535 Sector-2, Panchkula e-mail - [email protected] 2 Adarsh Kumar ADIT (Inv.) (HQ) Room No. - 208, 0172-2560168, Mob - 9530765400 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2582226 Sector-2, Panchkula 3 C. Chandrakanta Addl. DIT (Inv.) Room No. - 203, 0172-2582301, Mob. - 9530704451 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2357536 Sector-2, Panchkula e-mail - [email protected] 4 Sunil Kumar Yadav DDIT (Inv.)-II Room No. - 207, 0172-2583434, Mob - 9530706786 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2583434 Sector-2, Panchkula e-mail - [email protected] 5 SurendraMeena DDIT (Inv.)-I Room No. 209, 0172-2582855, Mob - 9530703198 Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2582855 Sector-2, Panchkula e-mail - [email protected] 6 Manveet Singh ADIT (Inv.)-III Room No. - 211, 0172-2585432 Sehgal Chandigarh Aayakar Bhawan, Fax-0172-2585432 Sector-2, Panchkula 7 Sunil Kumar Yadav DDIT (Inv.) Shimla Block No. 22, SDA 0177-2621567, Mob - 9530706786 Complex, Kusumpti, Fax-0177-2621567 Shimla-9 (H.P.) e-mail - [email protected] 8 Padi Tatung DDIT (Inv.) Ambala Aayakar Bhawan, 0171-2632839 AmbalaCantt Fax-0171-2632839 9 K.K. Mittal Addl. DIT (Inv.) New CGO Complex, B- 0129-24715981, Mob - 9818654402 Faridabad Block, NH-IV, NIT, 0129-2422252 Faridabad e-mail - [email protected] 10 Himanshu Roy ADIT (Inv.)-II New CGO Complex, B- 0129-2410530, Mob - 9468400458 Faridabad Block, NH-IV, NIT, Fax-0129-2422252 Faridabad e-mail - [email protected] 11 Dr.Vinod Sharma DDIT (Inv.)-I New CGO Complex, B- 0129-2413675, Mob - 9468300345 Faridabad Block, NH-IV, NIT, Faridabad e-mail - [email protected] 12 ShashiKajle DDIT (Inv.) Panipat SCO-44, Near Angel 0180-2631333, Mob - 9468300153 Mall, Sector-11, Fax-0180-2631333 Panipat e-mail - [email protected] 13 ShashiKajle (Addl. -

4055 Capital Outlay on Police

100 9 STATEMENT NO. 13-DETAILED STATEMENT OF Expenditure Heads(Capital Account) Nature of Expenditure 1 A. Capital Account of General Services- 4055 Capital Outlay on Police- 207 State Police- Construction- Police Station Office Building Schemes each costing Rs.one crore and less Total - 207 211 Police Housing- Construction- (i) Construction of 234 Constables Barracks in Policelines at Faridabad. (ii) Construction of Police Barracks in Police Station at Faridabad. (iii) Construction of Police Houses for Government Employees in General Pool at Hisar. (iv) Construction of Houses of Various Categories for H.A.P. at Madhuban . (v) Investment--Investment in Police Housing Corporation. (vi) Construction of Police Houses at Kurukshetra,Sonepat, and Sirsa. (vii) Other Schemes each costing Rs.one crore and less Total - 211 Total - 4055 4058 Capital Outlay on Stationery and Printing- 103 Government Presses- (i) Machinery and Equipments (ii) Printing and Stationery (iii) Extension of Government Press at Panchkula Total - 103 Total - 4058 4059 Capital Outlay on Public Works- 01 Office Buildings- 051 Construction- (i) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Fatehabad (ii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Jhajjar (iii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Panchkula (iv) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Yamuna Nagar (v) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Kaithal (vi) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Rewari (vii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Faridabad (viii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Bhiwani (ix) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Narnaul (x) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Jind (xi) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Sirsa (xii) Construction of Mini Secretariat at Hisar 101 CAPITAL EXPENDITURE DURING AND TO END OF THE YEAR 2008-2009 Expenditure during 2008-2009 Non-Plan Plan Centrally Sponsered Total Expenditure to Schemes(including end of 2008-2009 Central Plan Schemes) 23 4 5 6 (In thousands of rupees) . -

Government of India Ground Water Year Book of Haryana State (2015

CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVINATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK OF HARYANA STATE (2015-2016) North Western Region Chandigarh) September 2016 1 CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVINATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK OF HARYANA STATE 2015-2016 Principal Contributors GROUND WATER DYNAMICS: M. L. Angurala, Scientist- ‘D’ GROUND WATER QUALITY Balinder. P. Singh, Scientist- ‘D’ North Western Region Chandigarh September 2016 2 FOREWORD Central Ground Water Board has been monitoring ground water levels and ground water quality of the country since 1968 to depict the spatial and temporal variation of ground water regime. The changes in water levels and quality are result of the development pattern of the ground water resources for irrigation and drinking water needs. Analyses of water level fluctuations are aimed at observing seasonal, annual and decadal variations. Therefore, the accurate monitoring of the ground water levels and its quality both in time and space are the main pre-requisites for assessment, scientific development and planning of this vital resource. Central Ground Water Board, North Western Region, Chandigarh has established Ground Water Observation Wells (GWOW) in Haryana State for monitoring the water levels. As on 31.03.2015, there were 964 Ground Water Observation Wells which included 481 dug wells and 488 piezometers for monitoring phreatic and deeper aquifers. In order to strengthen the ground water monitoring mechanism for better insight into ground water development scenario, additional ground water observation wells were established and integrated with ground water monitoring database. -

Residential Plots for Advocates

POLICY FOR RESERVATION OF RESIDENTIAL PLOTS FOR ADVOCATES From The Chief Administrator, Haryana Urban Development Authority, Sector-6, Panchkula. To 1. All the Administrators of HUDA in the State. 2. All the Estate Officers of HUDA in the State. Memo No. UB-I-NK-2008/ 30928-48 Dated: 29.08.08 Subject : Regarding Reservation of Residential Plots for Advocates in HUDA Urban Estates- C.M.’s Announcement. 1. The issue of providing reservation of Residential Plots for Advocates in HUDA Urban Estates has been engaging the attention of the State Government for some time. In view of the Chief Minister’s announcement, it has now been decided that henceforth the reservation of residential plots for Advocates shall be made in HUDA sectors as follows- S. Zone %age of Plots No. to be reserved i) Hyper and High Potential Zones which include Nil a) Urban Estate of Gurgaon. (they can apply b) Controlled areas in Gurgaon District including for the plots as controlled area declared around Sohna town. general category c) Controlled areas of Panipat and Kundli– alongwith others) Sonepat Multi-Functional Urban Complex. d) Periphery Controlled areas of Panchkula. ii) Medium Potential Zone which includes 5% a) Controlled areas of Karnal, Kurukshetra, Ambala City, Ambala Cantt, Yamunanagar, Hisar, Rohtak, Rewari-Bawal-Dharuhera Complex, Gannaur, Oil Refinery Panipat (Beholi). (b) Controlled areas of Faridabad District including controlled areas around towns like Palwal and Hodel. iii) Low Potential Zone which includes all the 10% remaining controlled areas declared in the State. 2. The said allotment shall be governed by the following terms and conditions- a) The applicant must be a lawyer practicing in that Urban Estate, where he or she applies for a plot. -

Regionalism As Against Globalization: Survival of the Fittest

REGIONALISM AS AGAINST GLOBALIZATION: SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST - By HEMANT BATRA1 I. INTRODUCTION When the heads of state travel abroad, their entourage includes many chief business managers and executives. A couple of decades ago, military generals and admirals usually accompanied presidents or prime ministers on state visits. Military alliances or non-aggression treaties commonly occupied the agenda. Such peace policies have been replaced in recent years by commercial or trade policies, given the fact that the primary focus of all countries now a days is economic growth and development as this is what that determines the Global standing of a country in the present global scenario. Trade liberalization is widely recognized as a cornerstone of economic development and growth, and , ultimately poverty reduction. Global multilateral trading system offers the best prospect for reducing barriers to trade & achieving the greatest gains from trade liberalization and Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) are the next best means of trade liberalization. Thus FTA is a buzzword all over the world these days. Virtually every country wants to increase its exports. One way to make sure of it is to negotiate with its trading partners to lower trade barriers. 1 Hemant Batra is a Corporate, Business & Commercial Strategist Lawyer, whose practice is concentrated across the Globe in general, specifically in India. He is Director – Legal Services, Kaden Boriss Consulting Pvt. Ltd., a consulting company with multi-national promoters. Kaden Boriss is engaged in undertaking consulting assignments for clients, seeking to outsource their legal, para-legal and strategic advisory, regulatory and compliance work. In addition to the above he is also the Director of Thames Tobacco Company located in the United Kingdom. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -8 HARYANA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII-A&B VILLAGE, & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DIST.RICT BHIWANI Director of Census Operations Haryana Published by : The Government of Haryana, 1995 , . '. HARYANA C.D. BLOCKS DISTRICT BHIWANI A BAWAN I KHERA R Km 5 0 5 10 15 20 Km \ 5 A hAd k--------d \1 ~~ BH IWANI t-------------d Po B ." '0 ~3 C T :3 C DADRI-I R 0 DADRI - Il \ E BADHRA ... LOHARU ('l TOSHAM H 51WANI A_ RF"~"o ''''' • .)' Igorf) •• ,. RS Western Yamuna Cana L . WY. c. ·......,··L -<I C.D. BLOCK BOUNDARY EXCLUDES STATUtORY TOWN (S) BOUNDARIES ARE UPDATED UPTO 1 ,1. 1990 BOUNDARY , STAT E ... -,"p_-,,_.. _" Km 10 0 10 11m DI';,T RI CT .. L_..j__.J TAHSIL ... C. D . BLOCK ... .. ~ . _r" ~ V-..J" HEADQUARTERS : DISTRICT : TAHSIL: C D.BLOCK .. @:© : 0 \ t, TAH SIL ~ NHIO .Y'-"\ {~ .'?!';W A N I KHERA\ NATIONAL HIGHWAY .. (' ."C'........ 1 ...-'~ ....... SH20 STATE HIGHWAY ., t TAHSil '1 TAH SIL l ,~( l "1 S,WANI ~ T05HAM ·" TAH S~L j".... IMPORTANT METALLED ROAD .. '\ <' .i j BH IWAN I I '-. • r-...... ~ " (' .J' ( RAILWAY LINE WIT H STA110N, BROAD GAUGE . , \ (/ .-At"'..!' \.., METRE GAUGE · . · l )TAHSIL ".l.._../ ' . '1 1,,1"11,: '(LOHARU/ TAH SIL OAORI r "\;') CANAL .. · .. ....... .. '" . .. Pur '\ I...... .( VILLAGE HAVING 5000AND ABOVE POPULATION WITH NAME ..,." y., • " '- . ~ :"''_'';.q URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE- CLASS l.ltI.IV&V ._.; ~ , POST AND TELEGRAPH OFFICE ... .. .....PTO " [iii [I] DEGREE COLLE GE AND TECHNICAL INSTITUTION.. '" BOUNDARY . STATE REST HOuSE .TRAVELLERS BUNGALOW AND CANAL: BUNGALOW RH.TB .CB DISTRICT Other villages having PTO/RH/TB/CB elc. -

Licence Details Upto June 2012

Detailed List of Licences Granted by the Department in the State (Updated till June 2012) DISCLAIMER: All the contents of this table are only for general information only. They do not constitute advice and should not be relied upon in making (or refraining from making) any decision. The information provided is solely for user’s general information. While due care has been taken to make it accurate yet no guarantee of any kind is either expressed or implied. Either, Director General Town and Country Planning, Haryana or any of its employee shall not be liable under any condition for any legal action/damages direct or indirect arising from the use of this data.No representations, warranties or guarantees whatsoever are made as to the accuracy, adequacy, reliability, completeness, suitability or applicability of the information to a particular situation. The reader is requested to convey any discrepancy observed in the data to any/all of the following, along with supporting document, if any, to enable rectification of the information: 1. Sh T.C.Gupta, IAS, Director General, Town and Country Planning, Haryana <[email protected]>; 2. Sh J.S.Redhu, Chief Town Planner Haryana <[email protected]> 3. Sh P.P.Singh, DTP(HQ) <[email protected]> Sr. File ID Year Lic No Date Developer Name Purpose Area Dev Plan SECTOR Colony Name Valid Upto/ No. (acre) Renewed upto 1 LC-9A 1981 1 20/04/1981 DLF Universal Plotted 160.83 GURGAON 24,25,25A DLF PH-1 TO 3 GUR RPL 19/04/2001 Sr.