Sex and Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terms of Office

Terms of Office The Right Honourable Sir John Alexander Macdonald, 1 July 1867 - 5 November 1873, 17 October 1878 - 6 June 1891 The Right Honourable The Honourable Sir John A. Macdonald Alexander Mackenzie (1815-1891) (1822-1892) The Honourable Alexander Mackenzie, 7 November 1873 - 8 October 1878 The Honourable Sir John Joseph Caldwell Abbott, 16 June 1891 - 24 November 1892 The Right Honourable The Honourable The Right Honourable Sir John Joseph Sir John Sparrow Sir John Sparrow David Thompson, Caldwell Abbott David Thompson 5 December 1892 - 12 December 1894 (1821-1893) (1845-1894) The Honourable Sir Mackenzie Bowell, 21 December 1894 - 27 April 1896 The Right Honourable Sir Charles Tupper, 1 May 1896 - 8 July 1896 The Honourable The Right Honourable Sir Mackenzie Bowell Sir Charles Tupper The Right Honourable (1823-1917) (1821-1915) Sir Wilfrid Laurier, 11 July 1896 - 6 October 1911 The Right Honourable Sir Robert Laird Borden, 10 October 1911 - 10 July 1920 The Right Honourable The Right Honourable The Right Honourable Arthur Meighen, Sir Wilfrid Laurier Sir Robert Laird Borden (1841-1919) (1854-1937) 10 July 1920 - 29 December 1921, 29 June 1926 - 25 September 1926 The Right Honourable William Lyon Mackenzie King, 29 December 1921 - 28 June 1926, 25 September 1926 - 7 August 1930, 23 October 1935 - 15 November 1948 The Right Honourable The Right Honourable The Right Honourable Arthur Meighen William Lyon Richard Bedford Bennett, (1874-1960) Mackenzie King (later Viscount), (1874-1950) 7 August 1930 - 23 October 1935 The Right Honourable Louis Stephen St. Laurent, 15 November 1948 - 21 June 1957 The Right Honourable John George Diefenbaker, The Right Honourable The Right Honourable 21 June 1957 - 22 April 1963 Richard Bedford Bennett Louis Stephen St. -

Children: the Silenced Citizens

Children: The Silenced Citizens EFFECTIVE IMPLEMENTATION OF CANADA’S INTERNATIONAL OBLIGATIONS WITH RESPECT TO THE RIGHTS OF CHILDREN Final Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights The Honourable Raynell Andreychuk Chair The Honourable Joan Fraser Deputy Chair April 2007 Ce document est disponible en français. This report and the Committee’s proceedings are available online at www.senate-senat.ca/rights-droits.asp Hard copies of this document are available by contacting the Senate Committees Directorate at (613) 990-0088 or by email at [email protected] Membership Membership The Honourable Raynell Andreychuk, Chair The Honourable Joan Fraser, Deputy Chair and The Honourable Senators: Romeo Dallaire *Céline Hervieux-Payette, P.C. (or Claudette Tardif) Mobina S.B. Jaffer Noël A. Kinsella *Marjory LeBreton, P.C. (or Gerald Comeau) Sandra M. Lovelace Nicholas Jim Munson Nancy Ruth Vivienne Poy *Ex-officio members In addition, the Honourable Senators Jack Austin, George Baker, P.C., Sharon Carstairs, P.C., Maria Chaput, Ione Christensen, Ethel M. Cochrane, Marisa Ferretti Barth, Elizabeth Hubley, Laurier LaPierre, Rose-Marie Losier-Cool, Terry Mercer, Pana Merchant, Grant Mitchell, Donald H. Oliver, Landon Pearson, Lucie Pépin, Robert W. Peterson, Marie-P. Poulin (Charette), William Rompkey, P.C., Terrance R. Stratton and Rod A. Zimmer were members of the Committee at various times during this study or participated in its work. Staff from the Parliamentary Information and Research Service of the Library of Parliament: -

Circular No. 5^ ^

FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA BIOLOGICAL STATION, NANAIMO, B.C. Circular No. 5^ ^ LISTS OF TITLES OF PUBLICATIONS of the FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA 1955-1960 Prepared by R. L0 Maclntyre Office of the Chairman, Ottawa March, 1961 FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA BIOLOGICAL STATION, NANAIMO, B.C. If Circular No. 5# LISTS OF TITLES OF PUBLICATIONS of the FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA 1955-1960 Prepared by R. L, Maclntyre Office of the Chairman, Ottawa March, 1961 FOREWORD This list has been prepared to fill a need for an up-to-date listing of publications issued by the Fisheries Research Board since 1954. A comprehensive "Index and list of titles, publications of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 1901-1954" is available from the Queen's Printer, Ottawa, at 75 cents per copy. A new printed index and list of titles similar to the above Bulletin (No. 110) is planned for a few years hence. This will incorporate the publications listed herein, plus those issued up to the time the new Bulletin appears. All of the publications listed here may be pur chased from the Queen's Printer at the prices shown, with the exception of the Studies Series (yearly bindings of reprints of papers by Board staff which are published in outside journals). A separate of a paper shown listed under "Journal" or "Studies Series" may be obtained from the author or issuing establishment, if copies are still available. In addition to the publications listed, various *-,* Board establishments put out their own series of V Circulars. Enquiries concerning such processed material should be addressed to the Director of the Station con cerned. -

Recognition Report SEPTEMBER 1, 2018 THROUGH AUGUST 31, 2019

FY 2019 Recognition Report SEPTEMBER 1, 2018 THROUGH AUGUST 31, 2019 The University of Texas School of Law FY 2019 Recognition Report CONTENTS 2 Giving Societies Letter from the Dean 9 A Year in Numbers We’ve just completed another remarkable annual giving drive 11 Participation by Class Year at the law school. Here you will find our roster of devoted 34 Longhorn Loyal supporters who participated in the 2018-19 campaign. They are 47 Sustaining Scholars our heroes. 48 100% Giving Challenge The distinctive mission and historical hallmark of our law school is to provide a top-tier education to our students without 49 Planned Giving top-tier debt. Historically, we have done it better than anyone. 50 Women of Texas Law You all know it well; I’ll bet most of you would agree that 51 Texas Law Reunion 2020 coming to the School of Law was one of the best decisions you ever made. The value and importance of our mission is shown in the lives you lead. This Recognition Report honors the This great mission depends on support from all of our alumni. alumni and friends who gave generously I hope that if you’re not on the report for the year just ended, to The University of Texas School of Law you’ll consider this an invitation to be one of the first to get on from September 1, 2018 to August 31, next year’s list! 2019. We sincerely thank the individuals and organizations listed herein. They help Please help us to keep your school great. -

Canada January 2008

THE READING OF MACKENZIE KING by MARGARET ELIZABETH BEDORE A thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Canada January 2008 Copyright © Margaret Elizabeth Bedore, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-37063-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-37063-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

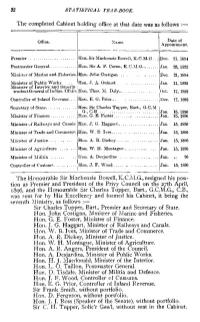

The Completed Cabinet Holding Office at That Date Was As Follows The

32 STATISTICAL YEARBOOK. The completed Cabinet holding office at that date was as follows Office. Date of Name. Appointment. Premier Hon. Sir Mackenzie Bowell, K.C.M.G. Dec. 21, 1894 Postmaster General Hon. Sir A. P. Caron, K.C.M.G Jan. 25, 1892 Minister of Marine and Fisheries. Hon. John Costigan Dec. 21, 1894 Minister of Public Works Hon. J. A. Ouimet Jan. 11, 1892 Minister of Interior and Superin tendent General of Indian Affairs Hon. Thos. M. Daly Oct. 17, 1892 Controller of Inland Revenue.... Hon. E. G. Prior Dec. 17, 1895 Secretary of State Hon. Sir Charles Tupper, Bart., G.C.M G., C.B Jan. 15, 1896 Minister of Finance Hon. G.E.Foster Jan. 15, 1896 Minister of Railways and Canals. Hon. J. G. Haggart Jan. 15, 1896 Minister of Trade and Commerce. Hon. W. B. Ives Jan. 15, 1896 Minister of Justice Hon. A. R.Dickey Jan. 15, 1896 Minister of Agriculture Hon. W. H. Montague . Jan. 15, 1896 Minister of Militia Hon. A. Desjardins .. Jan. .; 96 Controller of Custom0 Hon. J. F. Wood Jan. 15, 1896 The Honourable Sir Mackenzie Bowell, K.C.M.G., resigned his posi tion as Premier and President of the Privy Council on the 27th April, 1S96, and the Honourable Sir Charles Tupper, Bart., G.C.M.G., C.B., was sent for by His Excellency and formed his Cabinet, it being the seventh Ministry, as follows :— Sir Charles Tupper, Bart., Premier and Secretary of State. Hon. John Costigan, Minister of Marine and Fisheries. Hon. G. E. -

The Canadian Parliamentary Guide

NUNC COGNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J. BATA LI BRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY us*<•-« m*.•• ■Jt ,.v<4■■ L V ?' V t - ji: '^gj r ", •W* ~ %- A V- v v; _ •S I- - j*. v \jrfK'V' V ■' * ' ’ ' • ’ ,;i- % »v • > ». --■ : * *S~ ' iJM ' ' ~ : .*H V V* ,-l *» %■? BE ! Ji®». ' »- ■ •:?■, M •* ^ a* r • * «'•# ^ fc -: fs , I v ., V', ■ s> f ** - l' %% .- . **» f-•" . ^ t « , -v ' *$W ...*>v■; « '.3* , c - ■ : \, , ?>?>*)■#! ^ - ••• . ". y(.J, ■- : V.r 4i .» ^ -A*.5- m “ * a vv> w* W,3^. | -**■ , • * * v v'*- ■ ■ !\ . •* 4fr > ,S<P As 5 - _A 4M ,' € - ! „■:' V, ' ' ?**■- i.." ft 1 • X- \ A M .-V O' A ■v ; ■ P \k trf* > i iwr ^.. i - "M - . v •?*»-• -£-. , v 4’ >j- . *•. , V j,r i 'V - • v *? ■ •.,, ;<0 / ^ . ■'■ ■ ,;• v ,< */ ■" /1 ■* * *-+ ijf . ^--v- % 'v-a <&, A * , % -*£, - ^-S*.' J >* •> *' m' . -S' ?v * ... ‘ *•*. * V .■1 *-.«,»'• ■ 1**4. * r- * r J-' ; • * “ »- *' ;> • * arr ■ v * v- > A '* f ' & w, HSi.-V‘ - .'">4-., '4 -' */ ' -',4 - %;. '* JS- •-*. - -4, r ; •'ii - ■.> ¥?<* K V' V ;' v ••: # * r * \'. V-*, >. • s s •*•’ . “ i"*■% * % «. V-- v '*7. : '""•' V v *rs -*• * * 3«f ' <1k% ’fc. s' ^ * ' .W? ,>• ■ V- £ •- .' . $r. « • ,/ ••<*' . ; > -., r;- •■ •',S B. ' F *. ^ , »» v> ' ' •' ' a *' >, f'- \ r ■* * is #* ■ .. n 'K ^ XV 3TVX’ ■■i ■% t'' ■ T-. / .a- ■ '£■ a« .v * tB• f ; a' a :-w;' 1 M! : J • V ^ ’ •' ■ S ii 4 » 4^4•M v vnU :^3£'" ^ v .’'A It/-''-- V. - ;ii. : . - 4 '. ■ ti *%?'% fc ' i * ■ , fc ' THE CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY GUIDE AND WORK OF GENERAL REFERENCE I9OI FOR CANADA, THE PROVINCES, AND NORTHWEST TERRITORIES (Published with the Patronage of The Parliament of Canada) Containing Election Returns, Eists and Sketches of Members, Cabinets of the U.K., U.S., and Canada, Governments and Eegisla- TURES OF ALL THE PROVINCES, Census Returns, Etc. -

Money Just In.

i HE GLE V » VOL. IV. ALEXANDRIA, ONT., FRIDAY, JANUARY 17, 1896. NO. 51.^ M)TIC i:. visited .'rieiid.'? at Laggau last Friday even- MAXVILLE Endeavor principles, ladies and gentlemen Miss Ross, of McCormick, left 4L. L. McDOJS^ALD, M. D. ing. W. J. McCart, of Avonmorc, was in town taking part. } Creek on Saturday, where she pw dlcttgarn) ^tos. Mr. Archie Munro, of South Indian, llClI of those I. nUed jMr. A. Grant was in Alo.xaiulria. on on Thursday. spending some days with relatives. ALEXANDRIA, ONT. agent for potatoes was canvassing in town —la PCBLI8BEI>— DOORS, Crnii-t l[<ni'=c Covmvall, on Saturday. D. P. McDougall spent Friday in Mon- Office acd residence—Comer Of Main and Ttu'.-(lav.‘2Sth .Ii irv..\.l).,J::‘:i.Àat.-2p.m., pur- I)f. McDerniid, of k'ankleck lliil. was in on Tuesday. A Mr. Donald McPhec, son of Cou’ / EVERY FRIDAY MORNIK 0» Elgin Streets. sua'it to stiituti- town last Wednesday. ?.Iiss Maud McLaughlin, of Montreal, is Miss Aird, of Sandringham, is engaged D. D. McPhec, left on Monday- —AT THE— vrtl). ]b!iih as teacher in the school at the east end. Sash, Frames, WDKl.W I. M VCDONKLE. Our boys arc talking of getting up a the guest of Mrs. A. H. Edwards. resume bis studies at tho JesuiL . QLENOARRY “NEWS" PRINTING OFFICE Gouiif V Clerk, D. A ( lacrosse team next season, if such bo tlie Jas. G. Howdeu, of Montreal, was in A number from this vicinity attended MAIN STREET. ALEXANDRIA. ONT case, some of the older tcants around will town on Monday Rev. -

222 Furby Street, Young United Church

222 FURBY STREET YOUNG UNITED CHURCH HISTORICAL BUILDINGS COMMITTEE 31 October 1985 222 FURBY STREET YOUNG UNITED CHURCH Situated at the corner of Broadway and Furby Street, this large brick church is an important landmark in this west end neighbourhood. Originally Young Methodist, the present church consists of a 1906 building joined to a 1910 structure. The earlier section is on the west side, facing Broadway, while the 1910 section faces east onto Furby. At the present time the west portion contains the sanctuary while the east portion includes offices, classrooms and meeting space. While this Young Church structure belongs to the twentieth century, the church as a spiritual community had its origins in 1892 with the founding of the first young Methodist Church. Methodism was the largest of the Protestant churches in Canada at the time,1 having been established with British ties in the Maritimes in 1765 and infused with an American strain in Upper Canada with the arrival of the United Empire Loyalists. These two dominant strains were reinforced with subsequent immigrations and the national church united in 1874.2 This particular church recalls the name of Rev. George Young, an energetic missionary who first brought Methodism to the prairies in 1868.3 As the first of the Methodist circuit preachers, Rev. Young saw the mother church, Grace Methodist, established in Winnipeg as well as the founding of Wesley College, later United College and the University of Winnipeg.4 Certainly Young Church remains to honour the early Methodist missions in the prairie west, while the impact of the Methodist Church is substantial indeed. -

Prime Ministers and Government Spending: a Retrospective by Jason Clemens and Milagros Palacios

FRASER RESEARCH BULLETIN May 2017 Prime Ministers and Government Spending: A Retrospective by Jason Clemens and Milagros Palacios Summary however, is largely explained by the rapid drop in expenditures following World War I. This essay measures the level of per-person Among post-World War II prime ministers, program spending undertaken annually by each Louis St. Laurent oversaw the largest annual prime minister, adjusting for inflation, since average increase in per-person spending (7.0%), 1870. 1867 to 1869 were excluded due to a lack though this spending was partly influenced by of inflation data. the Korean War. Per-person spending spiked during World Our current prime minister, Justin Trudeau, War I (under Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden) has the third-highest average annual per-per- but essentially returned to pre-war levels once son spending increases (5.2%). This is almost the war ended. The same is not true of World a full percentage point higher than his father, War II (William Lyon Mackenzie King). Per- Pierre E. Trudeau, who recorded average an- person spending stabilized at a permanently nual increases of 4.5%. higher level after the end of that war. Prime Minister Joe Clark holds the record The highest single year of per-person spend- for the largest average annual post-World ing ($8,375) between 1870 and 2017 was in the War II decline in per-person spending (4.8%), 2009 recession under Prime Minister Harper. though his tenure was less than a year. Prime Minister Arthur Meighen (1920 – 1921) Both Prime Ministers Brian Mulroney and recorded the largest average annual decline Jean Chretien recorded average annual per- in per-person spending (-23.1%). -

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Ln History

"To each according to his need, and from each according to his ability. Why cannot the world see this?": The politics of William lvens, 1916-1936 by Michael William Butt A thesis presented to the University of Winnipeg in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts ln History Winnipeg, Manitoba (c) Michael William Butt, 1993 tl,Sonatolrbrav Bibliothèque nationale ffiWffi du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et Bibliographic Services Branch des services bibliog raphiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa (Ontario) K1A ON4 K1A ON4 Your lìle Volrc rélétence Out l¡le Nolre èlérence The author has granted an L'auteur a accordé une licence irrevocable non-exclusive Iicence irrévocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant à la Bibliothèque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationale du Canada de distribute or sell copies of reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa thèse in any form or format, making de quelque manière et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce so¡t pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette thèse à la disposition des person nes intéressées. The author retains ownership of L'auteur conserve la propriété du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qu¡ protège sa Neither the thesis nor substantial thèse. Ni la thèse ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiels de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent être imprimés ou his/her permission. autrement reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Gender and the Abolition of the Death Penalty in Canada a Case Study of Steven Truscott, 1959-1976 Nicki Darbyson

Document généré le 24 sept. 2021 15:09 Ontario History ‘Sadists and Softies:’ Gender and the Abolition of the Death Penalty in Canada A Case Study of Steven Truscott, 1959-1976 Nicki Darbyson Volume 103, numéro 1, spring 2011 Résumé de l'article Le 30 septembre 1959, Steven Turcott fut condamné à mort par pendaison pour URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1065478ar le viol et le meurtre de Lynne Harper. Son cas, le fait qu’il était, dans toute DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1065478ar l’histoire du Canada, le plus jeune condamné à mort, remirent au premier plan la question de la peine de mort, une question sur laquelle les Canadiens Aller au sommaire du numéro restaient toujours divisés. Dans cet article, à partir de ce cas, nous étudions comment le genre a influencé la manière dont les abolitionnistes étaient dépeints dans le débat sur la peine de mort durant les années 1966-1967, en Éditeur(s) pleine guerre froide. Les partisans de la peine de mort accusaient en effet alors les abolitionnistes d’être « mous » sur la question des crimes, d’être trop The Ontario Historical Society émotionnels, sentimentaux, et même, dans le cas des hommes, efféminés : on ne pouvait à la fois être un abolitionniste et être un « vrai homme ». Le débat ISSN sur la peine de mort révélait en fait l’insécurité des Canadiens quant au système judiciaire, et leurs peurs se manifestaient dans le discours, par des 0030-2953 (imprimé) références relatives au genre de chacun. 2371-4654 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Darbyson, N.