Mumblings from Munchkinland 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politics and Metaphysics in Three Novels of Philip K. Dick

EUGÊNIA BARTHELMESS Politics and Metaphysics in Three Novels of Philip K. Dick Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de Pós- Graduação em Letras, Área de Concentra- ção Literaturas de Língua Inglesa, do Setor de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes da Universidade Federai do Paraná, como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre. Orientadora: Prof.3 Dr.a BRUNILDA REICHMAN LEMOS CURITIBA 19 8 7 OF PHILIP K. DICK ERRATA FOR READ p -;2011 '6:€h|j'column iinesllll^^is'iiearly jfifties (e'jarly i fx|fties') fifties); Jl ' 1 p,.2Ò 6th' column line 16 space race space race (late fifties) p . 33 line 13 1889 1899 i -,;r „ i i ii 31 p .38 line 4 reel."31 reel • p.41 line 21 ninteenth nineteenth p .6 4 line 6 acien ce science p .6 9 line 6 tear tears p. 70 line 21 ' miliion million p .72 line 5 innocence experience p.93 line 24 ROBINSON Robinson p. 9 3 line 26 Robinson ROBINSON! :; 1 i ;.!'M l1 ! ! t i " i î : '1 I fi ' ! • 1 p .9 3 line 27 as deliberate as a deliberate jf ! •! : ji ' i' ! p .96 lin;e , 5! . 1 from form ! ! 1' ' p. 96 line 8 male dis tory maledictory I p .115 line 27 cookedly crookedly / f1 • ' ' p.151 line 32 why this is ' why is this I 1; - . p.151 line 33 Because it'll Because (....) it'll p.189 line 15 mourmtain mountain 1 | p .225 line 13 crete create p.232 line 27 Massachusetts, 1960. Massachusetts, M. I. T. -

Rd., Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock 37882; $1.50, Non-Member; $1.35, Member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; V15 N1 Entire Issue October 1972

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 091 691 CS 201 266 AUTHOR Donelson, Ken, Ed. TITLE Science Fiction in the English Class. INSTITUTION Arizona English Teachers Association, Tempe. PUB DATE Oct 72 NOTE 124p. AVAILABLE FROMKen Donelson, Ed., Arizona English Bulletin, English Dept., Ariz. State Univ., Tempe, Ariz. 85281 ($1.50); National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock 37882; $1.50, non-member; $1.35, member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; v15 n1 Entire Issue October 1972 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Booklists; Class Activities; *English Instruction; *Instructional Materials; Junior High Schools; Reading Materials; *Science Fiction; Secondary Education; Teaching Guides; *Teaching Techniques IDENTIFIERS Heinlein (Robert) ABSTRACT This volume contains suggestions, reading lists, and instructional materials designed for the classroom teacher planning a unit or course on science fiction. Topics covered include "The Study of Science Fiction: Is 'Future' Worth the Time?" "Yesterday and Tomorrow: A Study of the Utopian and Dystopian Vision," "Shaping Tomorrow, Today--A Rationale for the Teaching of Science Fiction," "Personalized Playmaking: A Contribution of Television to the Classroom," "Science Fiction Selection for Jr. High," "The Possible Gods: Religion in Science Fiction," "Science Fiction for Fun and Profit," "The Sexual Politics of Robert A. Heinlein," "Short Films and Science Fiction," "Of What Use: Science Fiction in the Junior High School," "Science Fiction and Films about the Future," "Three Monthly Escapes," "The Science Fiction Film," "Sociology in Adolescent Science Fiction," "Using Old Radio Programs to Teach Science Fiction," "'What's a Heaven for ?' or; Science Fiction in the Junior High School," "A Sampler of Science Fiction for Junior High," "Popular Literature: Matrix of Science Fiction," and "Out in Third Field with Robert A. -

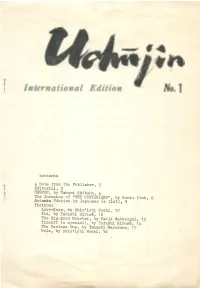

THE MYSTERIANS", by Norio Itoh, 6 Science Fiction in Japanese (A List

contents A Note from the Publisher, 2 Editorial, 3 MEGCON, by Takumi Shibano, 4 The Invasion of ’’THE MYSTERIANS", by Norio Itoh, 6 Science Fiction in Japanese (a list), 9 Fiction: ■ • Love-Keys, by Shin’ichi Hoshi, 10 Fit, by Tadashi Hirose, 12 The Big-Eyed Monster, by Taiji Matsuzaki, 13 TimemiT (a special), by Tadashi Hirose, 14 The Useless One, by Takashi Mayumura, 15 Hole, by Shin’ichi Hoshi, 16 A NOTE FROM THE PUBLISHER To senior SF fans all over the world, we have a. pleasure to present "UchÛjin": International Edition. This is the first English-edited fanzine in Japan. A Japanese word "Uchû” stands for Universe or Cosmos. "Uchû” consists of two words, "U" and "Chû". The former means Space and the latter Time. A v/ord Jin has. various meanings in Japanese, such as Man, Kidney, etc. In our case this word stands for Dust. So, the whole, meaning of "UchÛjin" is understood as Cosmic Dusts. We find innumerable particles of cosmic dusts floating in the nothingness, when we turn our eyes to the universe. Some of them may be attracted by gravity to planets or stars and burn up to meteors; others may keep floating indefinitely. And some "fortunate” ones among them may pull to each other and join together to be concentrated into a large heavenly body. Then it starts to shine brilliantly by itself in the darkness. This is the process that symbolizes "UchÛjin 1 and its fandom. Takumi Shibano EDITORIAL Uchûjin Club, alias Kagaku Sôsaku Club, alias Science Fiction Club, is the biggest fan club in Japan, but, to our disappointment, not the first one. -

Etherline 65

E T H w E I—t * z R L W B I N W O E c a S a n u £t/lQJlllTL e. t d b i o s e n C c d r i i o w t a p t o p e t d i b to B. o E •d e n t« n jl M w b cn s y f P o' 2 'A o o B t u I r o a w W >tx o to b n L - D l a A P i g M s r J h F CD d . FEATURING... > w e CO e a P d d -1 M C i A o .r* W s r , t b § o o y z 9 g i 6 0 e A s I 0 r p L , B M o“ i p r l A a y to r o m d Ol T ■S d a E e u l r e U c t IO •CJ o t G R o Oi rr. i n o f\/o^r/-/ r n o F r/j R v 2 IO A b o i: e N , y CD a CD d H to to CO T M , W) a A C <A> c w e CD S r a t Y to v u h y l o f n P i r e n U l R d E B . CO , a L oo B S CD s m’ I t . -

Exhibition List Jack Sharkey, the Secret Martians

MARCH-JUNE 2012 35c cabinet 14: ace double back sf cabinet 18 (large): non-fiction and omnibus sf Poul Anderson, Un-Man and Other Novellas. New York: Ace Life in the Twenty-First Century. Edited by M. Vassiliev and S. Books, 1962 Gouschev. London: Souvenir Press, 1960 Charles L. Fontenay, Rebels of the Red Planet. New York: Ace Murray Leinster, ‘First Contact’ in Stories for Tomorrow. Books, 1961 Selections and prefaces by William Sloane. London: Eyre & Gordon R. Dickson, Delusion World. New York: Ace Books, 1961 Spottiswoode, 1955 ___, Spacial Delivery. New York: Ace Books, 1961 I.M. Levitt, A Space Traveller’s Guide to Mars. London: Victor Margaret St. Clair, The Green Queen. New York: Ace Books, 1956 Gollancz, 1957 ____, The Games of Neith. New York: Ace Books, 1960 Men Against the Stars. Edited by Martin Greenberg. London: The Fred Fastier Science Fiction Collection Ray Cummings, Wandl the Invader. New York: Ace Books, 1961 Grayson & Grayson, 1951 Fritz Leiber, The Big Time. New York: Ace Books, 1961 Martin Caidin, Worlds in Space. London: Sidgwick and Poul Anderson, War of the Wing-Men. New York: Ace Books, 1958 Jackson, 1954 G. McDonald Wallis, The Light of Lilith. New York: Ace Patrick Moore, Science and Fiction. London: George G. Harrap Books, 1961 & Co., 1957 Exhibition List Jack Sharkey, The Secret Martians. New York: Ace Books, [1960] Aldous Huxley, Brave New World Revisited. London: Chatto & Eric Frank Russell, The Space Willies. New York: Ace Books, 1958 Windus, 1959 Robert A. W. Lowndes, The Puzzle Planet. New York: Ace J. B. Rhine, The Reach of the Mind. -

STEAM ENGINE TIME No

Steam Engine T ime Gregory Benford Paul Brazier Andrew M. Butler Darrell Schweitzer and many others Issue 4 January 2005 Steam Engine T ime 4 STEAM ENGINE TIME No. 4, January 2005 is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia ([email protected]) and Janine Stinson, PO Box 248, Eastlake, MI 49626-0248, USA ([email protected]). First edition is in .PDF file format from eFanzines.com or from either of our email addresses. Print edition available for The Usual (letters or substantial emails of comment, artistic contributions, articles, reviews, traded publications or review copies) or subscriptions (Australia: $40 for 5, cheques to ‘Gillespie & Cochrane Pty Ltd’; Overseas: $US30 or 12 pounds for 5, or equivalent, airmail; please send folding money, not cheques). Printed by Copy Place, 415 Bourke Street, Melbourne VIC 3000. The print edition is made possible by a generous financial donation from Our American Friend. Graphics Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) (front and back covers). Photographs Covers of various books and magazines discussed in this issue; plus photos of (p. 7) Darrell Schweitzer (unknown) and John Baxter (Dick Jenssen); (p. 8) Lee Harding, John Baxter and Mervyn Binns (Helena Binns); (p. 15) Andrew M. Butler (Paul Billinger). 3 Editorial 1: Unlikely resurrections 30 Letters of comment Bruce Gillespie and Janine Stinson E. D. Webber David J. Lake 3 Editorial 2: The journeys they took Sean McMullen Bruce Gillespie Tom Coverdale Rick Kennett Eric Lindsay 7 Tales of members of the Book Tribe Janine Stinson Darrell Schweitzer Joseph Nicholas Rob Gerrand 9 Epilogue: If the house caught fire . -

Science Fiction Review 31

SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW NUMBER 31 $1.75 Interview Andrew J. Offutt NOISE LEVEL John Brunner ON THE EDGE OF FUTURIA Ray Nelson THE ROGER AWARDS Orson Scott Card MOVIE NEWS AND REVIEWS Bill Warren THE VIVISECTOR Darrell Schweitzer SHORT FICTION REVIEWS Orson Scott Card PUBLISHING AND WRITING NEWS Elton T. Elliott BOOK REVIEWS - COfTENTARY - LEBERS O BOOK LISTS SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW ;,"8377i Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC P.O. BOX 11408 MAY, 1979 ---- VOL.8, NO.3 PORTLAND, OR 97211 WHOLE NUMBER 31 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & publisher PHOhE: (503) 282-0381 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN REVIEW-------- "AN76 is Astray" NEVER SAY DIE......................................... 14 SINGLE COPY ---- $1.75 STRANGE EONS............................................20 ALIEN THOUGHTS by the editor......... A ALDERAAN #4................................... 20 starship/algol ..............................a. TITAN........................................................... 22 INTERVIEW WITH ANDREW J. OFFUTT. .10 TRANSMANIACON......................................... 23 CONDUCTED BY DAVID A. TRUESDALE THE REDWARD EDWARD PAPERS.............. 26 LEITERS----------------- THE WONDERFUL VISIT............................27 CHARLES R. SAUNDERS 4 ODE TO GLEN A. LARSON THE BOOK OF CONQUESTS....................... 27 LUKE MCGUFF................ BY DEAN R. LAMBE.....................................14 SCIENCE FICTION: AN ILLUSTRATED GLEN T. WILSON......... HISTORY.......................................................28 HARRY ANDRUSCHAK... SCIENCE -

Exhibition Handlist

MARCH-JUNE 2012 35c : (): - Poul Anderson, Un-Man and Other Novellas. New York: Ace Life in the Twenty-First Century. Edited by M. Vassiliev and S. Books, 1962 Gouschev. London: Souvenir Press, 1960 Charles L. Fontenay, Rebels of the Red Planet. New York: Ace Murray Leinster, ‘First Contact’ in Stories for Tomorrow. Books, 1961 Selections and prefaces by William Sloane. London: Eyre & Gordon R. Dickson, Delusion World. New York: Ace Books, 1961 Spottiswoode, 1955 ___, Spacial Delivery. New York: Ace Books, 1961 I.M. Levitt, A Space Traveller’s Guide to Mars. London: Victor Margaret St. Clair, The Green Queen. New York: Ace Books, 1956 Gollancz, 1957 ____, The Games of Neith. New York: Ace Books, 1960 Men Against the Stars. Edited by Martin Greenberg. London: The Fred Fastier Science Fiction Collection Ray Cummings, Wandl the Invader. New York: Ace Books, 1961 Grayson & Grayson, 1951 Fritz Leiber, The Big Time. New York: Ace Books, 1961 Martin Caidin, Worlds in Space. London: Sidgwick and Poul Anderson, War of the Wing-Men. New York: Ace Books, 1958 Jackson, 1954 G. McDonald Wallis, The Light of Lilith. New York: Ace Patrick Moore, Science and Fiction. London: George G. Harrap Books, 1961 & Co., 1957 Exhibition List Jack Sharkey, The Secret Martians. New York: Ace Books, [1960] Aldous Huxley, Brave New World Revisited. London: Chatto & Eric Frank Russell, The Space Willies. New York: Ace Books, 1958 Windus, 1959 Robert A. W. Lowndes, The Puzzle Planet. New York: Ace J. B. Rhine, The Reach of the Mind. London: Faber and Faber, 1948 3 March to 15 June 2012 Books, 1961 P.