Big Shop of Horrors: Ownership in Theatrical Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

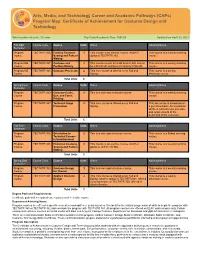

Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology

Arts, Media, and Technology Career and Academic Pathways (CAPs) Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology Total number of units: 23 units Top Code/Academic Plan: 1006.00 Updated on April 25, 2021 Fall Odd Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 366 Fantasy Costume 3 This course is an elective course. Another This course is a weekly morning Course Sewing and Pattern option is TECTHTR 365. course. Making Program/GE TECTHTR 367 Costume and 3 This course counts as a GE Area C Arts course This course is a weekly morning Course Fashion History for LACCD GE and Area C1 Arts for CSU GE. course. Program/GE TECTHTR 345 Costume Practicum 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This course is a weekly Course Spring. afternoon course. Total Units 8 Spring Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 363 Costume Crafts, 3 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a weekly morning Course Dye, and Fabric course. Printing Program TECTHTR 342 Technical Stage 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This lab course is scheduled on Course Production Spring. a per show basis. An orientation will be held to discuss schedule and requirements at the beginning of the semester. Total Units 5 Fall Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 305 Orientation to 2 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a Friday morning Course Technical Careers course. in Entertainment Program TECTHTR 365 Historical Costume 3 This course is an elective course. -

University of California Santa Cruz Dissecting

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ DISSECTING DRAMATURGICAL BODIES: Self, Sensibility, and Gaze in Contemporary Dramaturgy A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THEATER ARTS by Patrick Denney This thesis of Patrick Denney is Approved by: _____________________________________ Professor Michael Chemers, PHD, Chair _____________________________________ Professor Gerald Casel, MFA _____________________________________ Professor Philippa Kelly, PHD _____________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….iv Dedication………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………v “Killing” Theater: A Survey of Popular Depictions of Dramaturgy……………………………………………………………1 Brecht’s Electrons: Positioning the Dramaturg in The Messingkauf Dialogues and Beyond…………………….5 Doctor to Dramaturg, and Back Again: Defining the Dramaturgical Gaze………………………………………………10 Pharmaturg to Dramaturg: Pharmakos and Dionysian Dramaturgy………………………………………………………18 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….33 iii ABSTRACT: DISSECTING DRAMATURGICAL BODIES: Self, Sensibility, and Gaze in Contemporary Dramaturgy By Patrick Denney Dramaturgy is an art form that is still, after decades of existence in the American theater, misunderstood, and often feared, by many theater artists. From quasi-realistic portrayals of TV Shows such as SMASH, to the pulpy B-movie depiction of Law and Order: Criminal -

February March 2016

Tawas Bay Players Newsletter February/March 2016 TBP Tradition of Perchville Royalty Continues Congratulations Mike and Judy Merluzzi, the latest in a long line of Tawas Bay Players members to serve as Perchville King and Queen. This year was very special since last year’s king and queen TBP members Tim Haskin and Jolene Grusecki crowned Mike and Judy. Other TBP members to receive this honor were Carol Klenow, June Hudgins, Tara and Bill Western, Sharon Miller, Pat Ruster, Jo Ann Lutz, Brenda Chadwick, Deb DeBois, Judy Quarters, Lyle Groff and Keith Frank. Twelve Angry Jurors Our winter show, the fast paced courtroom drama, Twelve Angry Jurors opens this weekend. The show is directed by Deb DeBois assisted by Sharon Langley and is produced by June Hudgins. In addition to some of TBP’s finest actors this classic features many new faces. The cast includes Buck Weaver as the Judge, Terry Popielarz as the Guard and Sue Duncan, Beth Borowski, Chris Mundy, Eric Perrot, Wade Sydenstricker, Andre' De Wilde, Curtis Davenport, Michal Jacot, Le Roy Wenzel, Rodger McElveen, Waverley Monroe, and Sheilah Monroe as Jurors #1 through #12. We would like to welcome first time TBP performers Eric, Wade, Curtis, Waverley, and Sheliah to our stage and let Terry and Andre' know how happy we are to have them back. We finally get to see Sue Duncan on stage with a speaking part. Make sure you get a chance to see this thought provoking play. Performance dates are February 12, 13, 14, 18, 19, 20, & 21. Really Groovy Dinner Interrupted By Murder. -

THTR 433A/ '16 CD II/ Syllabus-9.Pages

USCSchool of Costume Design II: THTR 433A Thurs. 2:00-4:50 Dramatic Arts Fall 2016 Location: Light Lab/PDE Instructor: Terry Ann Gordon Office: [email protected]/ floating office Office Hours: Thurs. 1:00-2:00: by appt/24 hr notice Contact Info: [email protected], 818-636-2729 Course Description and Overview This course is designed to acquaint students with the requirements, process and expectations for Film/TV Costume Designers, supervisors and crew. Emphasis will be placed on all aspects of the Costume process; Design, Prep: script analysis,“scene breakdown”, continuity, research, and budgeting; Shooting schedules, and wrap. The supporting/ancillary Costume Arts and Crafts will also be discussed. Students will gain an historical overview, researching a variety of designers processes, aesthetics and philosophies. Viewing films and film clips will support critique and class discussion. Projects focused on specific design styles and varied media will further support an overview of techniques and concepts. Current production procedures, vocabulary and technology will be covered. We will highlight those Production departments interacting closely with the Costume Department. Time permitting, extra-curricular programs will include rendering/drawing instruction, select field trips, and visiting TV/Film professionals. Students will be required to design a variety of projects structured to enhance their understanding of Film/TV production, concept, style and technique . Learning Objectives The course goal is for students to become familiar with the fundamentals of costume design for TV/Film. They will gain insight into the protocol and expectations required to succeed in this fast paced industry. We will touch on the multiple variations of production formats: Music Video, Tv: 4 camera vs episodic, Film, Commercials, Styling vs Costume Design. -

Paul Taylor Dance Company’S Engagement at Jacob’S Pillow Is Supported, in Part, by a Leadership Contribution from Carole and Dan Burack

PILLOWNOTES JACOB’S PILLOW EXTENDS SPECIAL THANKS by Suzanne Carbonneau TO OUR VISIONARY LEADERS The PillowNotes comprises essays commissioned from our Scholars-in-Residence to provide audiences with a broader context for viewing dance. VISIONARY LEADERS form an important foundation of support and demonstrate their passion for and commitment to Jacob’s Pillow through It is said that the body doesn’t lie, but this is wishful thinking. All earthly creatures do it, only some more artfully than others. annual gifts of $10,000 and above. —Paul Taylor, Private Domain Their deep affiliation ensures the success and longevity of the It was Martha Graham, materfamilias of American modern dance, who coined that aphorism about the inevitability of truth Pillow’s annual offerings, including educational initiatives, free public emerging from movement. Considered oracular since its first utterance, over time the idea has only gained in currency as one of programs, The School, the Archives, and more. those things that must be accurate because it sounds so true. But in gently, decisively pronouncing Graham’s idea hokum, choreographer Paul Taylor drew on first-hand experience— $25,000+ observations about the world he had been making since early childhood. To wit: Everyone lies. And, characteristically, in his 1987 autobiography Private Domain, Taylor took delight in the whole business: “I eventually appreciated the artistry of a movement Carole* & Dan Burack Christopher Jones* & Deb McAlister PRESENTS lie,” he wrote, “the guilty tail wagging, the overly steady gaze, the phony humility of drooping shoulders and caved-in chest, the PAUL TAYLOR The Barrington Foundation Wendy McCain decorative-looking little shuffles of pretended pain, the heavy, monumental dances of mock happiness.” Frank & Monique Cordasco Fred Moses* DANCE COMPANY Hon. -

GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] +1(347)636.6681 AWARDS + HONORS SKILLS ASHLEY LAW EDUCATION WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL

ASHLEY LAW GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] http://ashleylaw.info +1(347)636.6681 linkedin.com/in/ashley-law instagram.com/_ashleylaw EDUCATION AWA RDS SKILLS SCHOOL OF VISUAL + GRAPHIS (GOLD) SOFTWARE ARTS (New York) NEW TALENT ANNUAL InDesign HONORS BFA Design Editorial Design “Zine”- Illustrator 2017–2019 2018 Photoshop PremierePro AfterEffects SCHOOL OF THE SVA HONOR’S LIST Sketch ART INSTITUTE OF 2017–2018 CHICAGO (Chicago) Fine Art + Visual CAPABILITIES & Critical Studies SAIC MERIT Branding 2013–2015 SCHOLARSHIP Content Production 2013–2015 Identity System Interactive/Digital Design Print + Editorial Design Typography WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL Junior Graphic Design for the GCL team focusing on CREATIVE LAB Designer creative direction of special projects, 06. 2019 - Present (New York) under the direction of Shu Hung and John Jay. Campaigns include collaborations (i.e. Lemaire, JW Anderson, Alexander Wang) and new store openings. MATTE PROJECTS Design Intern Designing client proposals, print, 01. 2019–04. 2019 (New York) digital & social collateral for marketing agency. Worked on projects for Cartier, The Chainsmokers, Moda Operandi & MATTE events (FNT, BLACK-NYC, Full Moon Festival, La Luna). PYT OPERANDI Creative Project Associate for artist management & creative 03–06. 2016 Associate project development company with emphasis (Hong Kong) in film, photography, exhibitions, project & business development consulting. CLOVER GROUP Intimates Design Designed for leading global manufacturer INTL LIMITED. Intern of intimate apparel, emphasis on the 08–10. 2015 (Hong Kong) Victoria’s Secret account. Visually detailed creative direction, identity & design of project pitches. Similar work for clients including Wacoal, Aerie, Lane Bryant. GIORGIO ARMANI Menswear R&D Shadowed Manager of R&D department OPERATIONS Intern for Menswear at HK Armani Corporate 06–09. -

Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association

For internal use only Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association. All rights reserved. Student(s): School: Selection: Troupe: 4 | Superior 3 | Excellent 2 | Good 1 | Fair SKILLS Above standard At standard Near standard Aspiring to standard SCORE Job Understanding Articulates a broad Articulates an Articulates a partial Articulates little and Interview understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the Articulation of the costume costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role designer’s role and specific and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; job responsibilities; thoroughly presents adequately presents and inconsistently presents does not explain an presentation and and explains the explains the executed and explains the executed executed design, creative explanation of the executed executed design, creative design, creative decisions, design, creative decisions decisions or collaborative design, creative decisions, decisions, and and collaborative process. and/or collaborative process. and collaborative process. collaborative process. process. Comment: Design, Research, A well-conceived set of Costume designs, Incomplete costume The costume designs, and Analysis costume designs, research, and script designs, research, and research, and analysis Design, research and detailed research, and analysis address the script analysis of the script do not analysis addresses the thorough script artistic and practical somewhat address the address the artistic and artistic and practical needs analysis clearly address needs of the production artistic and practical practical needs of the (given circumstances) of the artistic and practical and support the unifying needs of the production production or support the the script to support the needs of production and concept. -

To View Our Program

About Villanova University Since 1842, Villanova University’s Augustinian Catholic intellectual tradition has been the cornerstone of an academic community in which students learn to think critically, act compassionately and succeed while serving others. There are more than 10,000 undergraduate, graduate and law students in the Univer- sity’s six colleges – the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, the Villanova School of Business, the College of Engineering, the College of Nursing, the College of Professional Studies and the Villanova University School of Law. As students grow intellectually, Villanova prepares them to become ethical leaders who create positive change everywhere life takes them. In Gratitude The faculty, staff, and students of Villanova Theatre extend sincere gratitude to those generous benefactors who have established endowed funds in support of our efforts: Marianne M. and Charles P. Connolly, Jr. ’70 Dorothy Ann and Bernard A. Coyne, Ph.D. ̓55 Patricia M. ’78 and Joseph C. Franzetti ’78 Peter J. Lavezzoli ’60 Mary Anne C. Morgan ̓70 and Family & Friends of Brian G. Morgan ̓67, ̓70 Anthony T. Ponturo ’74 For information about how you can support the Theatre Department, please contact Heather Potts-Brown, Director of Annual Giving, at (610) 519-4583. Villanova Theatre gratefully acknowledges the generous support of its many patrons & subscribers We wish to offer special thanks to our 14-15 Benefactors: This list is updated as of November 1, 2014 A Running Friend Delia Mullaney Bill & Mimi Nolan John L. Abruzzo, M.D. Peggy & Bill Hill Beverly Nolan Donna Adams-Tomlinson Nancy & Joseph Hopko Dr. & Mrs. Bruce Northrup Loretta Adler Kerri L. -

Volume 2: Ptolemy II Software Architecture)

Heterogeneous Concurrent Modeling and Design in Java (Volume 2: Ptolemy II Software Architecture) Christopher Brooks Edward A. Lee Xiaojun Liu Stephen Neuendorffer Yang Zhao Haiyang Zheng Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences University of California at Berkeley Technical Report No. UCB/EECS-2007-8 http://www.eecs.berkeley.edu/Pubs/TechRpts/2007/EECS-2007-8.html January 11, 2007 Copyright © 2007, by the author(s). All rights reserved. Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise, to republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission. Acknowledgement This work was supported in part by the Center for Hybrid and Embedded Software Systems (CHESS) at UC Berkeley, which receives support from the National Science Foundation (NSF award #CCR-0225610), the State of California Micro Program, Rome AFRL, and the following companies: Agilent, DGIST, General Motors, Hewlett Packard, Infineon, Microsoft, National Instruments, and Toyota. PTOLEMY II HETEROGENEOUS CONCURRENT MODELING AND DESIGN IN JAVA Edited by: Christopher Brooks, Edward A. Lee, Xiaojun Liu, Steve Neuendorffer, Yang Zhao, Haiyang Zheng VOLUME 2: PTOLEMY II SOFTWARE ARCHITECTURE Authors: Shuvra S. Bhattacharyya Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences University of California at Berkeley Christopher Brooks I T Y • O F S • C R A http://ptolemy.eecs.berkeley.edu E A L V Elaine Cheong I I F N O U R • L John Davis, II N E E L T IG H T T I H H A E T R E BE • Mudit Goel Document Version 6.0 • •1 8 6 8• Bart Kienhuis for use with Ptolemy II 6.0 Edward A. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

Beautiful Family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble

SARAH BOCKEL (Carole King) is thrilled to be back on the road with her Beautiful family! Broadway/ First National Tour: Beautiful; Betty/ Ensemble. Regional: Million Dollar Quartet (Chicago); u/s Dyanne. Rocky Mountain Repertory Theatre- Les Mis; Madame Thenardier. Shrek; Dragon. Select Chicago credits: Bohemian Theatre Ensemble; Parade, Lucille (Non-eq Jeff nomination) The Hypocrites; Into the Woods, Cinderella/ Rapunzel. Haven Theatre; The Wedding Singer, Holly. Paramount Theatre; Fiddler on the Roof, ensemble. Illinois Wesleyan University SoTA Alum. Proudly represented by Stewart Talent Chicago. Many thanks to the Beautiful creative team and her superhero agents Jim and Sam. As always, for Mom and Dad. ANDREW BREWER (Gerry Goffin) Broadway/Tour: Beautiful (Swing/Ensemble u/s Gerry/Don) Off-Broadway: Sex Tips for Straight Women from a Gay Man, Cougar the Musical, Nymph Errant. Love to my amazing family, The Mine, the entire Beautiful team! SARAH GOEKE (Cynthia Weil) is elated to be joining the touring cast of Beautiful - The Carole King Musical. Originally from Cape Girardeau, Missouri, she has a BM in vocal performance from the UMKC Conservatory and an MFA in Acting from Michigan State University. Favorite roles include, Sally in Cabaret, Judy/Ginger in Ruthless! the Musical, and Svetlana in Chess. Special thanks to her vital and inspiring family, friends, and soon-to-be husband who make her life Beautiful. www.sarahgoeke.com JACOB HEIMER (Barry Mann) Theater: Soul Doctor (Off Broadway), Milk and Honey (York/MUFTI), Twelfth Night (Elm Shakespeare), Seminar (W.H.A.T.), Paloma (Kitchen Theatre), Next to Normal (Music Theatre CT), and a reading of THE VISITOR (Daniel Sullivan/The Public). -

Edition 5 | 2019-2020

SHUBERT THEATRE 2019–2020 SEASON CATS | 5 CATS Title Page | 7 CATS Cast | 9 CATS Scenes & Musical Numbers | 13 CATS Who’s Who | 15 CATS Staff | 26 Shubert Supporters | 28 The Shubert Theatre is located at 247 College Street, New Haven BOX OFFICE HOURS: Mon–Fri 9:30am–5:30pm and during all performances Call 203-562-5666 or 888-736-2663 www.shubert.com ADVERTISING Onstage Publications Advertising Department 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 e-mail: [email protected] www.onstagepublications.com This program is published in association with Onstage Publications, 1612 Prosser Ave., Dayton, Ohio 45409. This program may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher. Onstage Publications is a division of Just Business!, Inc. Contents © 2020. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. Shubert Theatre | 2019–2020 3 THE SHUBERT ORGANIZATION JAMES L. NEDERLANDER THE REALLY USEFUL GROUP CAMERON MACKINTOSH ROY FURMAN JOHN GORE STELLA LA RUE GROVE ENTERTAINMENT BURNT UMBER PRODUCTIONS INDEPENDENT PRESENTERS NETWORK/AL NOCCIOLINO PETER MAY PRESENT MUSIC BY ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER BASED ON “OLD POSSUM’S BOOK OF PRACTICAL CATS” BY T. S. ELIOT THE “CATS” COMPANY: ZACHARY S. BERGER JORDAN BETSCHER CAITLIN BOND ELYSE COLLIER ERIN CHUPINSKY MAURICE DAWKINS GIOVANNI DiGABRIELE PJ DiGAETANO ALEX DORF CAMERON EDRIS DANI GOLDSTEIN TIMOTHY GULAN DEVIN HATCH BRETT MICHAEL LOCKLEY McGEE MADDOX MADISON MITCHELL NATHAN PATRICK MORGAN ADRIANA NEGRON BRAYDEN NEWBY CHARLOTTE O’DOWD ALEXA RACIOPPI AUSTIN JOSEPH REYNOLDS ADAM RICHARDSON NEVADA RILEY ANNEMARIE ROSANO MELODY ROSE BEN SEARS ZACHARY TALLMAN TRICIA TANGUY ADAM VANEK DONNA VIVINO AND LORETTA WILLIAMS MUSIC SUPERVISION BY KRISTEN BLODGETTE MUSIC DIRECTOR ERIC KANG MUSIC COORDINATOR TALITHA FEHR CASTING BY TARA RUBIN CASTING / LINDSAY LEVINE, CSA AND XAVIER RUBIANO, CSA TOUR BOOKING, MARKETING AND PUBLICITY DIRECTION BOND THEATRICAL GROUP TOUR MANAGEMENT TROIKA ENTERTAINMENT PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT GREGG DAMANTI GENERAL MANAGEMENT KAREN BERRY PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER J.