Running up the Mountain of the Male Ego: Title IX and the Gender Hierarchy in Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Girl Who Ran: Bobbi Gibb Statue to Be Unveiled in April

Volume 5 | November 2019 The Girl Who Ran: Bobbi Gibb Statue to be Unveiled in April The Foundation’s goal to honor Bobbi Gibb, the first woman to run the Boston Marathon, has exceeded the second and final stage of its fundraising objectives, Foundation president Tim Kilduff announced recently, and a bronze statue of Bobbi will be installed in downtown Hopkinton just prior to the 2020 Boston Marathon in April. This second phase, whose goal was $26,200, brought in more than $32,000, thanks in part to Bobbi’s family and campaign guidance by Charity Team’s Susan Hurley. The statue, sculpted by Bobbi herself (shown), is being cast now by Buccacio Sculpture Services of Canton, Mass. More about Bobbi’s pioneering story can be found in The Girl Who Ran, whose publisher, Compendium, is donating signed copies of the book to those Crowdrise donors who contributed $100 (illustration from book, above). Find out more about Bobbi’s epic 1966 run and the sculpture project here and here. And, listen to a brand-new Boston Herald podcast here, in which the Foundation details the history of the project. Apply Now: ‘Team Inspire’ Bibs for Boston Going Fast As we write this, approximately 50 of the Foundation’s 65 invitational entries for the 2020 Boston Marathon have been spoken for, with runners from as far afield as the UK, Singapore, Hong Kong and Indonesia selected to represent ‘Team Inspire’. In return for the bibs, team runners have been asked to donate or fund-raise, with proceeds earmarked for the Foundation’s signature project, the development and construction of an International Marathon Center (IMC) in Hopkinton, MA. -

Tells Inspiring Story of First Woman to Run Boston Marathon New Children’S Illustrated Title Celebrates Bobbi Gibb and Her Historic Race

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Angeline Candido Compendium 206.812.1640 ext. 228 [email protected] “The Girl Who Ran” Tells Inspiring Story of First Woman to Run Boston Marathon New children’s illustrated title celebrates Bobbi Gibb and her historic race. SEATTLE (June 15, 2017) — In 1966, the world believed it was impossible for a woman to run the Boston Marathon and Bobbi Gibb proved them wrong. Compendium is honored to announce the release of “The Girl Who Ran”, an illustrated children’s book based on Gibb’s journey to become the first woman to run Boston Marathon. The book begins with Gibb as a young girl with a relentless desire to run “like the wind in the fire.” A visit to the Boston Marathon with her father ignited her dream to take part in the race. But her application was rejected by the Boston Athletic Association which informed her that women were incapable of running the marathon distance of 26.2 miles. People worried she would cause herself serious injury and thought that she was mentally ill. She proved them wrong and finished the race ahead of about half the men who were running, with a time of 3:21:40. Authors Frances Poletti and Kristina Yee worked to bring Gibb’s story to life. Illustrator Susanna Chapman visited the Boston Marathon and sketched runners, capturing the spirit and community of the race. A timeline on the back of the book gives a history on the Boston Marathon and the increasing number of women who joined each year. -

SENATE ...No. 2197

SENATE DOCKET, NO. FILED ON: 3/24/2016 SENATE . No. 2197 Resolutions (filed by Messrs. Tarr and Brady, Ms. L’Italien, Messrs. McGee and Joyce, Ms. Lovely, Mr. Timilty, Ms. Gobi, Ms. Donoghue, Mr. Lesser, Ms. O’Connor Ives, Ms. Chandler and Messrs. Eldridge and Fattman) “commending Roberta "Bobbi" Gibb on the fiftieth anniversary of her achievement as the first woman to run the Boston Marathon.” The Commonwealth of Massachusetts _______________ In the One Hundred and Eighty-Ninth General Court (2015-2016) _______________ Resolutions commending Roberta "Bobbi" Gibb on the fiftieth anniversary of her achievement as the first woman to run the Boston Marathon. 1 WHEREAS, ROBERTA “BOBBI” GIBB HAS BEEN NAMED THE 2016 GRAND 2 MARSHAL OF THE BOSTON MARATHON AND IS BEING HONORED ON THE 3 FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF HER FIRST BOSTON MARATHON RUN AND FOR HER 4 ACHIEVEMENT AS THE FIRST WOMAN TO RUN THE BOSTON MARATHON; AND 5 WHEREAS, BOBBI GIBB MADE HISTORY IN 1966 BY BECOMING THE FIRST 6 WOMAN TO COMPLETE THE BOSTON MARATHON, CROSSING THE FINISH LINE IN 7 3 HOURS, 21 MINUTES AND 40 SECONDS; AND 8 WHEREAS, BOBBI GIBB TRAINED FOR 2 YEARS TO COMPETE IN THE 9 BOSTON MARATHON ONLY TO BE TOLD AFTER SUBMITTING AN APPLICATION TO 10 RUN IN 1966 THAT WOMEN WERE NOT PERMITTED IN THE RACE UNDER RULES 11 SET BY THE AMATEUR ATHLETIC UNION WHICH BARRED WOMEN FROM 12 PARTICIPATING IN COMPETITIVE RACES LONGER THAN 1 AND 1/2 MILES; AND 1 of 3 13 WHEREAS, BOBBI GIBB NEVERTHELESS TRAVELED TO THE 14 COMMONWEALTH FROM CALIFORNIA, CONCEALED HER FACE AND HID NEAR 15 THE STARTING -

Kathrine Switzer: How One Run Broke the Barrier of Discrimination in Women's Athletics

1 Kathrine Switzer: How One Run Broke the Barrier of Discrimination in Women’s Athletics Marlena Olson and Sam Newitt Junior Division Group Documentary Process Paper: 499 words 2 Kathrine Switzer challenged societal and legal barriers against women participating in distance running as the first woman to complete the Boston Marathon. Her landmark run increased women’s participation in sports and paved the way for the passage of Title IX. We are interested in running, and after initially researching Bobbi Gibb’s story, we discovered Kathrine Switzer. Switzer’s 1967 Boston Marathon run had a large amount of press coverage, which provided primary sources, and showed the cultural importance of her run. We began our research by reading secondary sources; we determined that a knowledge base was necessary to interpret primary sources. Next, we began locating primary sources, including photographs and newspapers from the 1960s. Additionally, a teacher suggested we interview Dr. Laura Raeder, who has run a marathon in every U.S. state. She provided insight on the integration of women in marathon running. Our school librarian assisted us in locating databases for both primary and secondary sources. We downloaded more than fifty historical newspaper articles from Newspapers.com, and we read Marathon Woman, Switzer’s autobiography. These primary sources helped demonstrate initial reactions from 1967. Although we located an abundance of sources, there was one source we sought but were not able to use: a direct interview with Kathrine Switzer. We emailed Switzer’s media director and requested a Skype interview. Switzer was not able to fulfill our request, however, the director sent us a press folder. -

Updated 2019 Completemedia

April 15, 2019 Dear Members of the Media, On behalf of the Boston Athletic Association, principal sponsor John Hancock, and all of our sponsors and supporters, we welcome you to the City of Boston and the 123rd running of the Boston Marathon. As the oldest annually contested marathon in the world, the Boston Marathon represents more than a 26.2-mile footrace. The roads from Hopkinton to Boston have served as a beacon for well over a century, bringing those from all backgrounds together to celebrate the pursuit of athletic excellence. From our early beginnings in 1897 through this year’s 123rd running, the Boston Marathon has been an annual tradition that is on full display every April near and far. We hope that all will be able to savor the spirit of the Boston Marathon, regardless whether you are an athlete or volunteer, spectator or member of the media. Race week will surely not disappoint. The race towards Boylston Street will continue to showcase some of the world’s best athletes. Fronting the charge on Marathon Monday will be a quartet of defending champions who persevered through some of the harshest weather conditions in race history twelve months ago. Desiree Linden, the determined and resilient American who snapped a 33-year USA winless streak in the women’s open division, returns with hopes of keeping her crown. Linden has said that last year’s race was the culmination of more than a decade of trying to tame the beast of Boston – a race course that rewards those who are both patient and daring. -

NOT JUST a GAME Featuring Dave Zirin

MEDIA EDUCATION FOUNDATION STUDY GUIDE NOT JUST A GAME Featuring Dave Zirin Study Guide Written by SCOTT MORRIS please visit www.mediaed.org/wp/notjustagame for updated materials & resources 2 CONTENTS Note to Educators ………………………………………………………………………………………3 Program Overview ……………………………………………………………………………………...4 Pre-viewing Questions …………………………………………………………………………………4 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Key Points …………………………………………………………………………………………5 Questions for Discussion & Writing …………………………………………………………….5 Assignments ………………………………………………………………………………………6 In the Arena ……………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Key Points …………………………………………………………………………………………7 Questions for Discussion & Writing …………………………………………………………….8 Assignments ………………………………………………………………………………………9 Like a Girl ………………………………………………………………………………………………10 Key Points ……………………………………………………………………………………….10 Questions for Discussion & Writing …………………………………………………………...12 Assignments …………………………………………………………………………………….13 Breaking the Color Barrier ……………………………………………………………………………15 Key Points ……………………………………………………………………………………….15 Questions for Discussion & Writing …………………………………………………………...15 Assignments …………………………………………………………………………………….16 The Courage of Athletes ……………………………………………………………………………..18 Key Points ……………………………………………………………………………………….18 Questions for Discussion & Writing …………………………………………………………...19 Assignments …………………………………………………………………………………….20 3 NOTE TO EDUCATORS This study guide is designed to help you and your students engage and manage the information presented in this video. -

Discussion & Activity Guide

1 DISCUSSION & ACTIVITY GUIDE CONTENTS Page 2 Background / About the Author & Illustrator Page 3 Suggested Learning Activities www.PenguinClassroom.com facebook.com/PenguinClassroom @PenguinClass 2 BACKGROUND ★ "A bright salutation of a story, with one determined woman at its center." –Kirkus Reviews, starred review The inspiring story of the first female to run the Boston Marathon comes to life in stunningly vivid collage illustrations. Because Bobbi Gibb is a girl, she's not allowed to run on her school's track team. But after school, no one can stop her--and she's free to run endless miles to her heart's content. She is told no yet again when she tries to enter the Boston Marathon in 1966, because the officials claim that it's a man's race and that women are just not capable of running such a long distance. So what does Bobbi do? She bravely sets out to prove the naysayers wrong and show the world just what a girl can do. Text by Annette Bay Pimentel is based on Gibb’s autobiography, an interview with her, and historical research. Collage art by Micha Archer includes map elements. The back matter includes information about Gibb’s legacy and source information. ABOUT THE AUTHOR & ILLUSTRATOR Annette Bay Pimentel loves true stories about real people. She also wrote the picture book Mountain Chef: How One Man Lost His Groceries, Changed His Plans, and Helped Cook Up the National Park Service. She spends her days reading nonfiction picture books and reviewing them on her website, researching in libraries, and writing about the people she discovers. -

Running with the Girls

Inspiration comes in all packages, large and small, regardless of speed, strength or ability. Relish in the tales of these women as they take you through a journey that battles disease, hardships and death. Then, experience along with them as they embrace health, life and finding themselves again through running. In addition, learn where the sport of women's running has been, where it is, and where we can expect it to be in the future.. Running With the Girls by Lacie Whyte & Dane Rauschenberg Order the complete book from the publisher Booklocker.com http://booklocker.com/books/7804.html or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. YOUR FREE EXCERPT APPEARS BELOW. ENJOY! Running with the Girls Running with the Girls Lacie Whyte and Dane Rauschenberg i Lacie Whyte and Dane Rauschenberg Copyright © 2014 Lacie Whyte and Dane Rauschenberg ISBN 978-1-63490-071-3 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., Bradenton, Florida. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2014 First Edition 121414 ii Running with the Girls Contents FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................... IX INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. -

A Race with a Wide Reach

Volume 10 | July 2020 A Race with a Wide Reach The Boston Marathon is rather more than simply a 26.2-mile road race. Its inspiration and origins, in 1896, date back to the first modern Olympic Games. As the oldest continuous annual marathon in the world, it has become a renowned and highly recognized brand – arguably the frontrunner among the world’s marquee marathons. The race has no shortage of stakeholders, not least of all the Boston Athletic Association (B.A.A.). The impact of its cancellation this year reaches well beyond the hopes, dreams and training commitments of the tens of thousands who have met the B.A.A.’s qualifying standards. The thousands of runners who were extended the courtesy of invitational entries must feel it particularly acutely. In addition to their training, many of them spend months fundraising for local charities in return for their bib. It hits hard on the bottom line of the charities that depend on those donations, which last year totaled $38.7 million. It costs the city of Boston and surrounding region an estimated $211 million in lost revenues, particularly in the hospitality industry. It disappoints the 9,700 volunteers whose love of the race fuels their commitment and helps make the race work. And, of course, it silences the hundreds of thousands of spectators who line the route in what has become a rite of spring in New England. Each and every Marathon stakeholder faces an unprecedented situation for which there are few, if any, guidelines. But out of respect for all that the Boston Marathon is, and for all that it represents, it’s time to move beyond the shared disappointment. -

There's More to a Marathon Than Running 26.2 Miles

Volume 1 | February 2019 There's More to a Marathon than Running 26.2 Miles Friends, Welcome to the first edition of the 26.2 Foundation’s newsletter. You’re receiving this because you may be a marathoner, are involved in race management, supported someone who's run a marathon, or because you simply appreciate marathoning as an example of the power of the human spirit. We thank you sincerely for your interest and engagement. We like to say that there's more to a marathon than running 26.2 miles: inspiration, commitment, passion, preparation, courage, health, heritage, discipline and sportsmanship. We believe our dynamic programs, which are all designed to promote and support marathoning, reflect those qualities, and that they honor, celebrate and inspire those who run. Follow us and see what we mean. Thanks again for your support! Yours, Timothy Kilduff, President 26.2 Foundation's 'Team Inspire' Runs for a Cause Update: Advisory Considered one of the most Council to prestigious marathons in the Guide world, the BAA's Boston Marathon International has extremely challenging qualifying standards. Through the Marathon BAA's Charity & Community Center plans Partnerships program, which provides the 26.2 Foundation with Our sincere invitational (non-qualifying) thanks to the entries to the Boston Marathon, 40-plus runners who might not otherwise individuals who be able to participate in the convened recently for our inaugural Advisory Council Boston Marathon have an meeting. Influential legislators, businessmen and opportunity to do so while marathoners are providing their perspective on, and fundraising for our organization. guidance for, our biggest project yet, the Our fundraising team, "Team development of an International Marathon Center Inspire," comprises 15 runners (IMC), for which plans have been drawn and a site – who combine their passion for on the Boston Marathon route in Hopkinton, MA – running with a desire to support identified. -

2021 : RRCA Distance Running Hall of Fame : 1971 RRCA DISTANCE RUNNING HALL of FAME MEMBERS

2021 : RRCA Distance Running Hall of Fame : 1971 RRCA DISTANCE RUNNING HALL OF FAME MEMBERS 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 Bob Cambell Ted Corbitt Tarzan Brown Pat Dengis Horace Ashenfleter Clarence DeMar Fred Faller Victor Drygall Leslie Pawson Don Lash Leonard Edelen Louis Gregory James Hinky Mel Porter Joseph McCluskey John J. Kelley John A. Kelley Henigan Charles Robbins H. Browning Ross Joseph Kleinerman Paul Jerry Nason Fred Wilt 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 R.E. Johnson Eino Pentti John Hayes Joe Henderson Ruth Anderson George Sheehan Greg Rice Bill Rodgers Ray Sears Nina Kuscsik Curtis Stone Frank Shorter Aldo Scandurra Gar Williams Thomas Osler William Steiner 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 Hal Higdon William Agee Ed Benham Clive Davies Henley Gabeau Steve Prefontaine William “Billy” Mills Paul de Bruyn Jacqueline Hansen Gordon McKenzie Ken Young Roberta Gibb- Gabe Mirkin Joan Benoit Alex Ratelle Welch Samuelson John “Jock” Kathrine Switzer Semple Bob Schul Louis White Craig Virgin 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 Nick Costes Bill Bowerman Garry Bjorklund Dick Beardsley Pat Porter Ron Daws Hugh Jascourt Cheryl Flanagan Herb Lorenz Max Truex Doris Brown Don Kardong Thomas Hicks Sy Mah Heritage Francie Larrieu Kenny Moore Smith 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 Barry Brown Jeff Darman Jack Bacheler Julie Brown Ann Trason Lynn Jennings Jeff Galloway Norm Green Amby Burfoot George Young Fred Lebow Ted Haydon Mary Decker Slaney Marion Irvine 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Ed Eyestone Kim Jones Benji Durden Gerry Lindgren Mark Curp Jerry Kokesh Jon Sinclair Doug Kurtis Tony Sandoval John Tuttle Pete Pfitzinger 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Miki Gorman Patti Lyons Dillon Bob Kempainen Helen Klein Keith Brantly Greg Meyer Herb Lindsay Cathy O’Brien Lisa Rainsberger Steve Spence 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Deena Kastor Jenny Spangler Beth Bonner Anne Marie Letko Libbie Hickman Meb Keflezighi Judi St. -

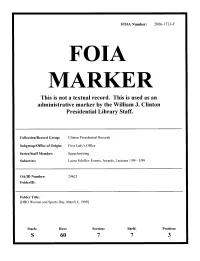

This Is Not a Textual Record. This Is Used As an Administrative Marker by the William J

FOIA Number: 2006-1733-F FOIA MARKER This is not a textual record. This is used as an administrative marker by the William J. Clinton Presidential Library Staff. Collection/Record Group: Clinton Presidential Records Subgroup/Office of Origin: First Lady's Office Series/Staff Member: Speechwriting Subseries: Laura Schiller: Events, Awards, Lectures 1/99 - 3/99 OA/ID Number: 24625 FolderlD: Folder Title: [HBO Women and Sports Day, March 4, 1999] Stack: Row: Section: Shelf: Position: S 60 7 7 3 FIRST LADY HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON REMARKS AT LAB SCHOOL NEW YORK, NEW YORK MARCH 4, 1999 Thank you all. I am delighted to be here at the Lab School. I want to thank Sophia Totti [Toe-Tee], for all she said today...and for all she's done over the years to bring leadership, style and victory to the Lady Gators. Now, I have to confess that earlier, a few people told me that you might appreciate it if I started my remarks with my own version of the song, "YMCA." What they didn't realize is that the only area where I have less talent than sports is in singing. But I do have a deep appreciation for other people's talent ~ and so I am delighted to have brought along some great athletes and role models. Not just great female athletes. But, some of the greatest athletes of all time: Billie Jean King, Nikki McCray, and Dominique Dawes. Thank you so much for coming. I am also very pleased that we are joined today by so many elected officials [the Manhattan Burough President Virginia Fields; State Senator Thomas Duane; Assemblymember Richard Gottfried; Councilmembers Kathryn Freed, Gifford Miller, Ronnie Eldridge, Bill Perkins, and Guillermo Linares.