Designing Civic Stages for Democratic Participation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top Five Reasons to Shop Crystal Lake During the Holidays…

City of Crystal Lake, Illinois City of Crystal Lake, Illinois November 2016 C i t y L e t t e r Inside: New Three Oaks Interactive Map New E-City Letter Sign Up American Terra Cotta & Ceramic Co. The Saturday after Thanksgiving is Small Business Saturday. Make plans now to, “Shop Big at Small Shops” in Crystal Lake! Follow “I Shop Crystal Lake” on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram for information about special holiday activities, trivia and business offers. Top Five Reasons to Shop Crystal Lake During The Holidays…. 5 Crystal Lake retailers have everything you need this holiday season – Home goods, toys, books, tools, apparel, electronics and more! 4 Two-thirds of every dollar spent in Crystal Lake stays in the local economy. 3 Festival of Lights Parade on Black Friday in Downtown Crystal Lake – Shop & see Santa at his house downtown. 2 There are hundreds of wonderful and unique shops and restaurants throughout Crystal Lake - Come shop, stay and make a day of checking gifts for people off your list. 1 “Local supports Local” – Shopping Crystal Lake supports local businesses that provide important products and services to residents. *Photo Courtesy of Paul McPherson November 2016 | City Letter 1 www.CrystalLake.org Crystal Lake Police Department “Honoring All Who Served” Coffee with the Chief The Crystal Lake Police Department wishes all the “Distracted driving consistently ranks as one of the Veterans in our community who have served in the U.S. traffic safety issues at the forefront of many drivers’ Armed Forces a Happy Veterans Day. Thank you for thinking.” (www.aaafoundation.org) your sacrifice and dedication to our country. -

The Fringe Insurgency Connectivity, Convergence and Mainstreaming of the Extreme Right

The Fringe Insurgency Connectivity, Convergence and Mainstreaming of the Extreme Right Jacob Davey Julia Ebner About this paper About the authors This report maps the ecosystem of the burgeoning Jacob Davey is a Researcher and Project Coordinator at ‘new’ extreme right across Europe and the US, which is the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD), overseeing the characterised by its international outlook, technological development and delivery of a range of online counter- sophistication, and overtures to groups outside of the extremism initiatives. His research interests include the traditional recruitment pool for the extreme-right. This role of communications technologies in intercommunal movement is marked by its opportunistic pragmatism, conflict, the use of internet culture in information seeing movements which hold seemingly contradictory operations, and the extreme-right globally. He has ideologies share a bed for the sake of achieving provided commentary on the extreme right in a range common goals. It examines points of connectivity of media sources including The Guardian, The New York and collaboration between disparate groups and Times and the BBC. assesses the interplay between different extreme-right movements, key influencers and subcultures both Julia Ebner is a Research Fellow at the Institute for online and offline. Strategic Dialogue (ISD) and author of The Rage: The Vicious Circle of Islamist and Far-Right Extremism. Her research focuses on extreme right-wing mobilisation strategies, cumulative extremism and European terrorism prevention initiatives. She advises policy makers and tech industry leaders, regularly writes for The Guardian and The Independent and provides commentary on broadcast media, including the BBC and CNN. © ISD, 2017 London Washington DC Beirut Toronto This material is offered free of charge for personal and non-commercial use, provided the source is acknowledged. -

Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right

Maik Fielitz, Nick Thurston (eds.) Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right Political Science | Volume 71 Maik Fielitz, Nick Thurston (eds.) Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right Online Actions and Offline Consequences in Europe and the US With kind support of Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for com- mercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting [email protected] Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely with the party re-using the material. © 2019 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Typeset by Alexander Masch, Bielefeld Printed by Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-4670-2 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-4670-6 https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839446706 Contents Introduction | 7 Stephen Albrecht, Maik Fielitz and Nick Thurston ANALYZING Understanding the Alt-Right. -

Social Media and Democracy : the State of the Field, Prospects for Reform

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.19, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:20:02, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/E79E2BBF03C18C3A56A5CC393698F117 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.33.19, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:20:02, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/E79E2BBF03C18C3A56A5CC393698F117 Social Media and Democracy Over the last five years, widespread concern about the effects of social media on democracy has led to an explosion in research from different disciplines and corners of academia. This book is the first of its kind to take stock of this emerging multi-disciplinary field by synthesizing what we know, identifying what we do not know and obstacles to future research, and charting a course for the future inquiry. Chapters by leading scholars cover major topics – from disinformation to hate speech to political advertising – and situate recent developments in the context of key policy questions. In addition, the book canvasses existing reform proposals in order to address widely perceived threats that social media poses to democracy. This title is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core. Nathaniel Persily is the James B. McClatchy Professor of Law at Stanford Law School and the Co-Director of the Stanford Cyber Policy Center and Stanford Project on Democracy and the Internet. His scholarship focuses on the law and technology of democracy. -

The Disinformation Age

Steven Livingston W. LanceW. Bennett EDITED BY EDITED BY Downloaded from terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/1F4751119C7C4693E514C249E0F0F997THE DISINFORMATION AGE https://www.cambridge.org/core Politics, and Technology, Disruptive Communication in the United States the United in https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms . IP address: 170.106.202.126 . , on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:34:36 , subject to the Cambridge Core Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.126, on 27 Sep 2021 at 12:34:36, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/1F4751119C7C4693E514C249E0F0F997 The Disinformation Age The intentional spread of falsehoods – and attendant attacks on minorities, press freedoms, and the rule of law – challenge the basic norms and values upon which institutional legitimacy and political stability depend. How did we get here? The Disinformation Age assembles a remarkable group of historians, political scientists, and communication scholars to examine the historical and political origins of the post-fact information era, focusing on the United States but with lessons for other democracies. Bennett and Livingston frame the book by examining decades-long efforts by political and business interests to undermine authoritative institutions, including parties, elections, public agencies, science, independent journalism, and civil society groups. The other distinguished scholars explore the historical origins and workings of disinformation, along with policy challenges and the role of the legacy press in improving public communication. This title is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core. W. Lance Bennett is Professor of Political Science and Ruddick C. -

Community Based Tourism Handbook by Potjana Suansri

Community Based Tourism Handbook By Potjana Suansri (Responsible Ecological Social Tour-REST) Community Based Tourism Handbook Author : Potjana Suansri Translated by : Bongkot Sewatarmra Krisda Momtakhob Jamie LeJeune Peter Richards Illustrations by : Praparat Kiatreongwit Designed and Printed by : Mild Publishing Funded by : Canada Fund Published by : Responsible Ecological Social Tour-REST First published in Thailand 2003 by REST Project All right reserved ISBN : 974-91433-7-X 2 Contents Acknowledgement 7 Foreword "Please - Don't pass by" 8 Chapter 1 Community Based Tourism: Principles and Meaning 9 1. Underlying Ideas 2. Community Based Tourism (CBT) 3. Terms and Definitions for Types of Tourism Similar to CBT 4. CBT and Community Development 5. The Process of Facilitating the Development of CBT Chapter 2 Choosing a Destination 25 1. Community Potential 2. Market Potential of CBT 3. Government Policy and the Role of the Local Government in Supporting CBT 4. Facilitating Organization and Funding Chapter 3 Completing a Feasibility Study with the Community 39 1. Community Goals and Motivation for Developing CBT 2. Understanding CBT 3. The Positive and Negative Impacts of Tourism 4. The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Community 5. Participatory Analysis Chapter 4 Tourism Vision and Objectives 55 1. The Meaning and Importance of Determining Vision 2. Determining a Vision for CBT 3. Tourism Objectives 3 Chapter 5 Planning 59 1. Planning 2. Important Elements of Planning 3. Planning Strategies 4. Making a Plan 5. Elements of Building Community Capacity 6. Planning to Market CBT 7. Planning for Monitoring and Evaluation Chapter 6 Administrative Organization 67 1. Important Elements of a CBT Administrative Organization 2. -

The Tea Party Movement

The Tea Party Movement: Grassroots Advocacy at its Finest, or Highly-Disguised Astroturfing? by Kassandra Zukowski A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Approved November 2011 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Majia Holmer Nadesan Lindsey Mean Ramsey Eric Ramsey ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2011 ABSTRACT Using models identified by communications scholars Herbert W. Simons and Charles J. Stewart, a rhetorical analysis was conducted on contemporary Tea Party Movement (TPM) artifacts in an attempt to gauge the movement's authenticity as it relates to grassroots advocacy versus astroturfing. The models provided a theoretical framework in which the functions of social movement leaders were analyzed, as well as the rhetorical phases of a movement. Additionally, the notions of advocacy and astroturfing were defined and the concepts compared and contrasted. Used in conjunction with one another the models provided a framework in which TPM artifacts could be analyzed. Analysis was conducted on the websites for the Tea Party Patriots and Tea Party Express, a one-month sample of Sarah Palin FaceBook posts, two speeches delivered by Michelle Bachmann, and finally one speech given by Palin. Examples for each of the necessary rhetorical components identified were found within TPM sources, thus leading to the conclusion that the TPM operates primarily as a grassroots advocacy movement. i TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER Page 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... -

Mapping Connective Actions in the Global Alt-Right and Antifa Counterpublics

International Journal of Communication 14(2020), 1070–1091 1932–8036/20200005 Mapping Connective Actions in the Global Alt-Right and Antifa Counterpublics WEIAI WAYNE XU University of Massachusetts, Amherst, USA The study examines how the Alt-Right and the Antifa counterpublics build counteridentities and influences through three connective actions: crowdsourced gatekeeping, hashtag- based framing, and political jamming. By studying social networks of Twitter-based information flows and semantic networks based on hashtag co-occurrence, coupled with bot-detection algorithms, the study presents how counterpublics build like-minded communities for information sharing and use Twitter mentions to seek rapport with fellow counterpublic members and challenge ideological opponents. Both counterpublics adopt counteractions to varying degrees in the form of oppositional framing, mockery, and trolls. Their hashtags suggest that the Alt-Right is a transnational alliance of populism and ethnonationalism capitalizing on U.S. President Donald Trump and his Make America Great Again movement, whereas Antifa’s identity is more decentralized and activist-oriented, defined by progressive causes, offline rallies, and cyber operations. The results of the study shed light on digitally mediated counterpublics and how connective actions support their goals. Keywords: counterpublic, connective action, collective action, Alt-Right, Antifa, social media Fringe political groups are on the rise globally. Representing two factions on opposing ends of the ideological spectrum are the Alt-Right and Antifa. The Alt-Right (alternative right) is a loosely connected group of people who are sympathetic to the cause of far-right populism and ethnonationalism (Lyons, 2017). Long eschewed by establishment conservatives, the Alt-Right has distinguished itself by its opposition to multiculturalism, globalization, and the elite (Lyons, 2017). -

Ku Klux Klan

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. KU \ , I, KLUX KLAN A REPORT TO THE ILLINOIS GENERAL ASSEMBLY t;J ~ . ~t ., E J : li,:( {.:.<~ ~,' i .,i i " ,.~ i 1 , .. ,p~~ ; £~C(, .:~.~} ... t <.) ~ '":~~:~ ,~ \ BYTHE ILLINOIS LEGISLATIVE INVESTIGATING COMMISSION 300 West Washington Street, Chicago, Illinois 60606 Telephone (312) 793-2606 ,= OCTOBER 1976 I. Printed bv the Authoritv of the State of Illinois Twenty-Five Hundred Copies TABLE OF CONTENTS HOUSE RESOLUTION 146.................................. iii LETTER TO HONORABLE MEMBERS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY... v INTRODUCTION. • . • . 1 Chapter 1 HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF THE KU KLUX KLAN A. Introduction.............................. 3 B. Origin of the Ku Klux Klan................ 3 C. Transformation and Growth of the Ku Klux Klan. ... 5 D. Decline of the Klan....................... 10 E. Romanticizing the Klan.................... 11 F. Resurrection of the Ku Klux Klan.......... 16 G. 1950's Klan Revival....................... 23 H. F.B.I. Investigation Breaks the Klan...... 27 I. Present Klan Organizations................ 29 Chapter 2 ORGANIZATION OF THE KU KLUX KLAN A. Introduction.............................. 31 B. Invi sible Empire ......................... It 32 C. Adminis'trative and Command Structure...... 32 D. Purposes of the KKK....................... 35 E. Functions of Local Klans .............. ,... 37 F. A Final Comment on Klan Organization...... 38 Chapter 3 BRIEF HIS~ORY OF THE KLAN IN ILLINOIS A. Introduction.............................. 39 B. The Klan in Illinois during the 1920s..... 39 C. Later Klan Activity....................... 41 Chapter 4 ILLINOIS KLAN'S INITIAL ORGANIZATIONAL ACTIVITY A. Background. 43 B. The Illinois Klan's Early Organizational Efforts.................................... 44 C. Initial Infiltration of the Illinois Klan ...................... ~ . .. .. 45 D. Split in the Illinois Klan Leadership.... -

Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (Edcs) 9

An Assessment Report on Issues of Concern: Chemicals and Waste Issues Posing Risks to Human Health and the Environment Annexes Table of Contents A. Supporting Information on Existing Instruments and Actions to Address the Issues of Concern under SAICM ����������������������������������������5 1. Chemicals in Products (CiP) 6 2. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) 9 3. Environmentally Persistent Pharmaceutical Pollutants (EPPPs) 14 4. Hazardous Substances in the Life Cycle of Electrical and Electronic Products (HSLEEP) 17 5. Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs) 24 6. Lead in Paint 29 7. Nanotechnology and Manufactured Nanomaterials 31 8. Per- and Polyfluoralkyl Substances (PFASs) 34 B. Supporting Information on Assessment of Issues Where Emerging Evidence Indicates Risks Identified by GCO-II ���������������������������39 1. Arsenic 40 2. Bisphenol A (BPA) 45 3. Cadmium 57 4. Glyphosate 63 5. Lead 71 6. Microplastics 79 7. Neonicotinoids 87 8. Organotins 97 9. Phthalates 102 10. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) 110 11. Triclosan 114 C. Annex References �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������129 A.1. CiP 131 A.2. EDCs 132 A.3. EPPPs 135 A.4. HSLEEP 136 A.5. HHPs 138 A.6. Lead in Paint 140 A.7. Nanotechnology and Manufactured Nanomaterials 140 A.8. PFASs 142 B.1. Arsenic 143 B.2. BPA 145 B.3. Cadmium 164 B.4. Glyphosate 167 B.5. Lead 168 B.6. Microplastics 172 B.7. Neonicotinoids 174 B.8. Organotins 177 B.9. Phthalates 179 B.10. PAHs 182 B.11. Triclosan 184 Image credits All images by © Thomas Kast A. Supporting Information on Existing Instruments and Actions to Address the Issues of Concern under SAICM 1. -

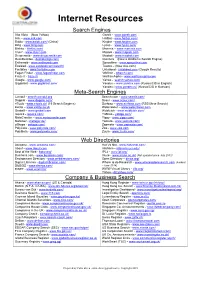

Internet Resources

Internet Resources Search Engines Alta Vista – (Now Yahoo) Gseek - www.gseek.com Ask – www.ask.com HotBot - www.hotbot.com/ Baidu - www.baidu.com/ (China) Kngine - www.kngine.com Bing - www.bing.com Lycos - www.lycos.com/ Blekko - blekko.com/ Mamma – www.mamma.com Cluuz - www.cluuz.com Mojeek - www.mojeek.com Deeperweb - www.deeperweb.com Mozbot - www.mozbot.com DuckDuckGo - duckduckgo.com/ Quintura – (Now a children’s Search Engine) Entireweb - www.entireweb.com Spacetime - www.spacetime.com Exalead - www.exalead.com/search/ Teoma – (Now Ask.com) Factbites - www.factbites.com Untabbed - untabbed.com (Google Results) Fagan Finder - www.faganfinder.com WbSrch - wbsrch.com/ Fraze It - fraze.it/ WolframAlpha - www.wolframalpha.com Google - www.google.com/ Yahoo - search.yahoo.com/ Gigablast - www.gigablast.com/ Yandex – www.yandex.com (Russia/CIS in English) Yandex - www.yandex.ru/ (Russia/CIS in Russian) Meta-Search Engines Carrot2 - search.carrot2.org Search.com - www.search.com/ Dogpile - www.dogpile.com/ Scour - www.scour.com/ eTools - www.etools.ch/ (15 Search Engines) Surfwax – www.surfwax.com (RSS Meta-Search) Excite – www.excite.co.uk Webcrawler – www.webcrawler.com Graball – www.graball.com Webfetch - www.webfetch.com/ Ixquick - ixquick.com/ YaBiGo - yabigo.com/ MetaCrawler – www.metacrawler.com Yippy - www.yippy.com/ MetaGer - metager.de/ Yometa - www.yometa.com/ oSkope - oskope.com/ Zapmeta - www.zapmeta.com/ PolyCola - www.polycola.com/ Zoo - www.zoo.com PolyMeta - www.polymeta.com/ Zuula - www.zuula.com/ Web Directories Accoona -

Effects of At-Work Break Activities on Recovery Experiences

ARE SOCIAL MEDIA BAD FOR YOUR EMPLOYEES? EFFECTS OF AT-WORK BREAK ACTIVITIES ON RECOVERY EXPERIENCES, JOB SATISFACTION, AND LIFE SATISFACTION A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by YI-SUNG CHENG Dr. Seonghee Cho, Dissertation Supervisor May 2019 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled ARE SOCIAL MEDIA BAD FOR YOUR EMPLOYEES? EFFECTS OF AT-WORK BREAK ACTIVITIES ON RECOVERY EXPERIENCES, JOB SATISFACTION, AND LIFE SATISFACTION presented by Yi-Sung Cheng, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Seonghee Cho, Ph.D., Department of Hospitality Management Dae-Young Kim, Ph.D., Department of Hospitality Management Pei Liu, Ph.D., Department of Hospitality Management KangJae Lee, Ph.D., Department of Parks, Recreation & Tourism Management ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to express the deepest appreciation to my committee chair Dr. Seonghee Cho, for the patient guidance, support and encouragement she has provided throughout my time as her doctoral student. I have been very lucky to have a supervisor who cared so much about my work and life. As my advisor and mentor, she has shaped who I am as a researcher and instructor. I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Dae-Young Kim, Dr. Pei Liu, and Dr. KangJae Lee, for the valuable comments and suggestions they made on my dissertation to help me get results of better quality.