Quantum Cryptography: a Survey∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(CST Part II) Lecture 14: Fault Tolerant Quantum Computing

Quantum Computing (CST Part II) Lecture 14: Fault Tolerant Quantum Computing The history of the universe is, in effect, a huge and ongoing quantum computation. The universe is a quantum computer. Seth Lloyd 1 / 21 Resources for this lecture Nielsen and Chuang p474-495 covers the material of this lecture. 2 / 21 Why we need fault tolerance Classical computers perform complicated operations where bits are repeatedly \combined" in computations, therefore if an error occurs, it could in principle propagate to a huge number of other bits. Fortunately, in modern digital computers errors are so phenomenally unlikely that we can forget about this possibility for all practical purposes. Errors do, however, occur in telecommunications systems, but as the purpose of these is the simple transmittal of some information, it suffices to perform error correction on the final received data. In a sense, quantum computing is the worst of both of these worlds: errors do occur with significant frequency, and if uncorrected they will propagate, rendering the computation useless. Thus the solution is that we must correct errors as we go along. 3 / 21 Fault tolerant quantum computing set-up For fault tolerant quantum computing: We use encoded qubits, rather than physical qubits. For example we may use the 7-qubit Steane code to represent each logical qubit in the computation. We use fault tolerant quantum gates, which are defined such thata single error in the fault tolerant gate propagates to at most one error in each encoded block of qubits. By a \block of qubits", we mean (for example) each block of 7 physical qubits that represents a logical qubit using the Steane code. -

Arxiv:Quant-Ph/9705031V3 26 Aug 1997 Eddt Rvn Unu Optrfo Crashing

CALT-68-2112 QUIC-97-030 quant-ph/9705031 Reliable Quantum Computers John Preskill1 California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA Abstract The new field of quantum error correction has developed spectacularly since its origin less than two years ago. Encoded quantum information can be protected from errors that arise due to uncontrolled interactions with the environment. Recovery from errors can work effectively even if occasional mistakes occur during the recovery procedure. Furthermore, encoded quantum information can be processed without serious propagation of errors. Hence, an arbitrarily long quantum computation can be performed reliably, provided that the average probability of error per quantum gate is less than a certain critical value, the accuracy threshold. A quantum computer storing about 106 qubits, with a probability of error per quantum gate of order 10−6, would be a formidable factoring engine. Even a smaller, less accurate quantum computer would be able to perform many useful tasks. This paper is based on a talk presented at the ITP Conference on Quantum Coherence and Decoherence, 15-18 December 1996. 1 The golden age of quantum error correction Many of us are hopeful that quantum computers will become practical and useful computing devices some time during the 21st century. It is probably fair to say, though, that none of us can now envision exactly what the hardware of that machine of the future will be like; surely, it will be much different than the sort of hardware that experimental physicists are investigating these days. But of one thing we can be quite confident—that a practical quantum computer will incorporate some type of error correction into its operation. -

LI-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf

FAULT-TOLERANCE ON NEAR-TERM QUANTUM COMPUTERS AND SUBSYSTEM QUANTUM ERROR CORRECTING CODES A Dissertation Presented to The Academic Faculty By Muyuan Li In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Computational Science and Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology May 2020 Copyright c Muyuan Li 2020 FAULT-TOLERANCE ON NEAR-TERM QUANTUM COMPUTERS AND SUBSYSTEM QUANTUM ERROR CORRECTING CODES Approved by: Dr. Kenneth R. Brown, Advisor Department of Electrical and Computer Dr. C. David Sherrill Engineering School of Chemistry and Biochemistry Duke University Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Edmond Chow Dr. Richard Vuduc School of Computational Science and School of Computational Science and Engineering Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. T.A. Brian Kennedy Date Approved: March 19, 2020 School of Physics Georgia Institute of Technology I think it is safe to say that no one understands quantum mechanics. R. P. Feynman To my family and my friends. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Ken Brown, who has guided me through my graduate studies with his patience, wisdom, and generosity. He has always been supportive and helpful, and always makes himself available when I needed. I have been constantly inspired by his depth of knowledge in research, as well as his immense passion for life. I would also like to thank my committee members, Professors Edmond Chow, T.A. Brian Kennedy, C. David Sherrill, and Richard Vuduc, for their time and helpful sugges- tions. One half of my graduate career was spent at Georgia Tech and the other half at Duke University. -

Assessing the Progress of Trapped-Ion Processors Towards Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computation

PHYSICAL REVIEW X 7, 041061 (2017) Assessing the Progress of Trapped-Ion Processors Towards Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computation A. Bermudez,1,2 X. Xu,3 R. Nigmatullin,4,3 J. O’Gorman,3 V. Negnevitsky,5 P. Schindler,6 T. Monz,6 U. G. Poschinger,7 C. Hempel,8 J. Home,5 F. Schmidt-Kaler,7 M. Biercuk,8 R. Blatt,6,9 S. Benjamin,3 and M. Müller1 1Department of Physics, College of Science, Swansea University, Singleton Park, Swansea SA2 8PP, United Kingdom 2Instituto de Física Fundamental, IFF-CSIC, Madrid E-28006, Spain 3Department of Materials, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3PH, United Kingdom 4Complex Systems Research Group, Faculty of Engineering and IT, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia 5Institute for Quantum Electronics, ETH Zürich, Otto-Stern-Weg 1, 8093 Zürich, Switzerland 6Institute for Experimental Physics, University of Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria 7Institut für Physik, Universität Mainz, Staudingerweg 7, 55128 Mainz, Germany 8ARC Centre for Engineered Quantum Systems, School of Physics, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 9Institute for Quantum Optics and Quantum Information of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria (Received 24 May 2017; revised manuscript received 11 August 2017; published 13 December 2017) A quantitative assessment of the progress of small prototype quantum processors towards fault-tolerant quantum computation is a problem of current interest in experimental and theoretical quantum information science. We introduce a necessary and fair criterion for quantum error correction (QEC), which must be achieved in the development of these quantum processors before their sizes are sufficiently big to consider the well-known QEC threshold. -

Entangled Many-Body States As Resources of Quantum Information Processing

ENTANGLED MANY-BODY STATES AS RESOURCES OF QUANTUM INFORMATION PROCESSING LI YING A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy CENTRE FOR QUANTUM TECHNOLOGIES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2013 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. LI YING 23 July 2013 Acknowledgments I am very grateful to have spent about four years at CQT working with Leong Chuan Kwek. He always brings me new ideas in science and has helped me to establish good collaborative relationships with other scien- tists. Kwek helped me a lot in my life. I am also very grateful to Simon C. Benjamin. He showd me how to do high quality researches in physics. Simon also helped me to improve my writing and presentation. I hope to have fruitful collaborations in the near future with Kwek and Simon. For my project about the ground-code MBQC (Chapter2), I am thank- ful to Tzu-Chieh Wei, Daniel E. Browne and Robert Raussendorf. In one afternoon, Tzu-Chieh showed me the idea of his recent paper in this topic in the quantum cafe, which encouraged me to think about the ground- code MBQC. Dan and Robert have a high level of comprehension on the subject of the MBQC. And we had some very interesting discussions and communications. I am grateful to Sean D. -

Classical Zero-Knowledge Arguments for Quantum Computations

Classical zero-knowledge arguments for quantum computations Thomas Vidick∗ Tina Zhangy Abstract We show that every language in BQP admits a classical-verifier, quantum-prover zero-knowledge ar- gument system which is sound against quantum polynomial-time provers and zero-knowledge for classical (and quantum) polynomial-time verifiers. The protocol builds upon two recent results: a computational zero-knowledge proof system for languages in QMA, with a quantum verifier, introduced by Broadbent et al. (FOCS 2016), and an argument system for languages in BQP, with a classical verifier, introduced by Mahadev (FOCS 2018). 1 Introduction The paradigm of the interactive proof system is a versatile tool in complexity theory. Although traditional complexity classes are usually defined in terms of a single Turing machine|NP, for example, can be defined as the class of languages which a non-deterministic Turing machine is able to decide|many have reformulations in the language of interactive proofs, and such reformulations often inspire natural and fruitful variants on the traditional classes upon which they are based. (The class MA, for example, can be considered a natural extension of NP under the interactive-proof paradigm.) Intuitively speaking, an interactive proof system is a model of computation involving two entities, a verifier and a prover, the former of whom is computationally efficient, and the latter of whom is unbounded but untrusted. The verifier and the prover exchange messages, and the prover attempts to `convince' the verifier that a certain problem instance is a yes-instance. We can define some particular complexity class as the set of languages for which there exists an interactive proof system that 1) is complete, 2) is sound, and 3) has certain other properties which vary depending on the class in question. -

G53NSC and G54NSC Non Standard Computation Research Presentations

G53NSC and G54NSC Non Standard Computation Research Presentations March the 23rd and 30th, 2010 Tuesday the 23rd of March, 2010 11:00 - James Barratt • Quantum error correction 11:30 - Adam Christopher Dunkley and Domanic Nathan Curtis Smith- • Jones One-Way quantum computation and the Measurement calculus 12:00 - Jack Ewing and Dean Bowler • Physical realisations of quantum computers Tuesday the 30th of March, 2010 11:00 - Jiri Kremser and Ondrej Bozek Quantum cellular automaton • 11:30 - Andrew Paul Sharkey and Richard Stokes Entropy and Infor- • mation 12:00 - Daniel Nicholas Kiss Quantum cryptography • 1 QUANTUM ERROR CORRECTION JAMES BARRATT Abstract. Quantum error correction is currently considered to be an extremely impor- tant area of quantum computing as any physically realisable quantum computer will need to contend with the issues of decoherence and other quantum noise. A number of tech- niques have been developed that provide some protection against these problems, which will be discussed. 1. Introduction It has been realised that the quantum mechanical behaviour of matter at the atomic and subatomic scale may be used to speed up certain computations. This is mainly due to the fact that according to the laws of quantum mechanics particles can exist in a superposition of classical states. A single bit of information can be modelled in a number of ways by particles at this scale. This leads to the notion of a qubit (quantum bit), which is the quantum analogue of a classical bit, that can exist in the states 0, 1 or a superposition of the two. A number of quantum algorithms have been invented that provide considerable improvement on their best known classical counterparts, providing the impetus to build a quantum computer. -

![Arxiv:0905.2794V4 [Quant-Ph] 21 Jun 2013 Error Correction 7 B](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5772/arxiv-0905-2794v4-quant-ph-21-jun-2013-error-correction-7-b-1115772.webp)

Arxiv:0905.2794V4 [Quant-Ph] 21 Jun 2013 Error Correction 7 B

Quantum Error Correction for Beginners Simon J. Devitt,1, ∗ William J. Munro,2 and Kae Nemoto1 1National Institute of Informatics 2-1-2 Hitotsubashi Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 101-8340. Japan 2NTT Basic Research Laboratories NTT Corporation 3-1 Morinosato-Wakamiya, Atsugi Kanagawa 243-0198. Japan (Dated: June 24, 2013) Quantum error correction (QEC) and fault-tolerant quantum computation represent one of the most vital theoretical aspect of quantum information processing. It was well known from the early developments of this exciting field that the fragility of coherent quantum systems would be a catastrophic obstacle to the development of large scale quantum computers. The introduction of quantum error correction in 1995 showed that active techniques could be employed to mitigate this fatal problem. However, quantum error correction and fault-tolerant computation is now a much larger field and many new codes, techniques, and methodologies have been developed to implement error correction for large scale quantum algorithms. In response, we have attempted to summarize the basic aspects of quantum error correction and fault-tolerance, not as a detailed guide, but rather as a basic introduction. This development in this area has been so pronounced that many in the field of quantum information, specifically researchers who are new to quantum information or people focused on the many other important issues in quantum computation, have found it difficult to keep up with the general formalisms and methodologies employed in this area. Rather than introducing these concepts from a rigorous mathematical and computer science framework, we instead examine error correction and fault-tolerance largely through detailed examples, which are more relevant to experimentalists today and in the near future. -

Introduction to Quantum Error Correction

Schrödinger Cats, Maxwell’s Demon and Quantum Error Correction Experiment Theory Michel Devoret SMG Luigi Frunzio Liang Jiang Rob Schoelkopf Leonid Glazman M. Mirrahimi ** Andrei Petrenko Nissim Ofek Shruti Puri Reinier Heeres Yaxing Zhang Philip Reinhold Victor Albert** Yehan Liu Kjungjoo Noh** Zaki Leghtas Richard Brierley Brian Vlastakis Claudia De Grandi +….. Zaki Leghtas Juha Salmilehto Matti Silveri Uri Vool Huaixui Zheng Marios Michael +….. QuantumInstitute.yale.edu Quantum Error Correction ‘Logical’ qubit Cold bath Entropy ‘Physical’ qubits ‘Physical’ Maxwell N Demon N qubits have errors N times faster. Maxwell demon must overcome this factor of N – and not introduce errors of its own! (or at least not uncorrectable errors) 2 Full Steane Code – Arbitrary Errors Single round of error correction 6 ancillae 7 qubits All previous attempts to overcome the factor of N and reach the ‘break even’ point of QEC have failed. Current industrial approach (IBM, Google, Intel, Rigetti): Scale up, then error correct • Large, complex: o Non-universal (Clifford gates only) o Measurement via many wires o Difficult process tomography • Large part count • Fixed encoding ‘Surface Code’ (readout wires not shown) O’Brien et al. arXiv:1703.04136 predict ‘break-even’ will be difficult even at the 50 qubit scale. 4 All previous attempts to overcome the factor of N and reach the ‘break even’ point of QEC have failed. We need a simpler and better idea... ‘Error correct and then scale up!’ Don’t use material objects as qubits. Use microwave photon states stored -

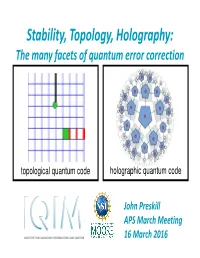

Stability, Topology, Holography: the Many Facets of Quantum Error Correction

Stability, Topology, Holography: The many facets of quantum error correction topological quantum code holographic quantum code John Preskill APS March Meeting 16 March 2016 Frontiers of Physics short distance long distance complexity Higgs boson Large scale structure “More is different” Neutrino masses Cosmic microwave Many-body entanglement background Supersymmetry Phases of quantum Dark matter matter Quantum gravity Dark energy Quantum computing String theory Gravitational waves Quantum spacetime ??? Quantum Supremacy! particle collision molecular chemistry entangled electrons A quantum computer can simulate efficiently any physical process that occurs in Nature. (Maybe. We don’t actually know for sure.) superconductor black hole early universe Decoherence 1 2 ( + ) Environment Decoherence 1 2 ( + ) Environment Decoherence explains why quantum phenomena, though observable in the microscopic systems studied in the physics lab, are not manifest in the macroscopic physical systems that we encounter in our ordinary experience. Quantum Computer Decoherence Environment To resist decoherence, we must prevent the environment from “learning” about the state ERROR! of the quantum computer during the computation. Quantum error correction …. This This This This This …. Page Page Page Page Page Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Environment The protected “logical” quantum information is encoded in a highly entangled state of many physical qubits. The environment can't access this information if it interacts locally with the protected system. Unruh, Physical -

Quantum Ciphertext Authentication and Key Recycling with the Trap Code

Quantum Ciphertext Authentication and Key Recycling with the Trap Code Yfke Dulek Qusoft, Centrum voor Wiskunde en Informatica, Amsterdam, the Netherlands [email protected] Florian Speelman1 QMATH, Department of Mathematical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Denmark [email protected] Abstract We investigate quantum authentication schemes constructed from quantum error-correcting codes. We show that if the code has a property called purity testing, then the resulting authentication scheme guarantees the integrity of ciphertexts, not just plaintexts. On top of that, if the code is strong purity testing, the authentication scheme also allows the encryption key to be recycled, partially even if the authentication rejects. Such a strong notion of authentication is useful in a setting where multiple ciphertexts can be present simultaneously, such as in interactive or delegated quantum computation. With these settings in mind, we give an explicit code (based on the trap code) that is strong purity testing but, contrary to other known strong-purity-testing codes, allows for natural computation on ciphertexts. 2012 ACM Subject Classification Theory of computation → Cryptographic protocols, Theory of computation → Error-correcting codes, Security and privacy → Information-theoretic techniques, Security and privacy → Symmetric cryptography and hash functions, Theory of computation → Quantum information theory Keywords and phrases quantum authentication, ciphertext authentication, trap code, purity- testing codes, quantum computing on encrypted data Digital Object Identifier 10.4230/LIPIcs.TQC.2018.1 Related Version https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.02237 (full version) Acknowledgements We thank Gorjan Alagic, Christian Majenz, and Christian Schaffner for valuable discussions and useful input at various stages of this research. Aditionally, we thank Christian Schaffner for his comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. -

Quantum Error Correction1

QUANtum error correction1 Quantum Error Correction James Sayre M.D. Department of Physics, University of Washington Author Note James Sayre Department of Physics University of Washington QUANtum error correction2 Abstract Quantum Computing holds enormous promise. Theoretically these computers should be able to scale exponentially in speed and storage. This spectacular capability comes at a price. Qubits are the basic storage unit. The information they store degrades over time due to decoherence and quantum noise. This degradation must be controlled if not eliminated. An entire field of inquiry is devoted to this is the function of quantum error correction. This paper starts with a discussion of the theoretical underpinnings of quantum error correction. Various methods are then described in detail. Keywords: Quantum Computing, Error Correction, Threshold Theorem, Shor’s Algorithm, Steane Code, Shor’s Code. QUANtum error correction3 Quantum Error Correction Quantum Computing holds enormous promise. A useful quantum computer will have the capability to perform searches, factorizations and quantum mechanical simulations far beyond the capability of classical computers [1] [2]. For instance, such a computer running Shor’s algorithm will be able to factorize a large number in polynomial time [3]. This is a tremendous speed advantage over a classical computer that requires exponential time to complete the same task. In theory a computation that requires millions of years on a classical computer could take hours on a quantum computer. The basic building block of a quantum computer is a qubit. Analogous to a classical bit, the qubit combines with other qubits to store numbers. Unlike classical computers, that storage grows exponentially with the number of qubits.