Chapter 5 Geometry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Parallelepiped Based Approach

3D Modelling Using Geometric Constraints: A Parallelepiped Based Approach Marta Wilczkowiak, Edmond Boyer, and Peter Sturm MOVI–GRAVIR–INRIA Rhˆone-Alpes, 38330 Montbonnot, France, [email protected], http://www.inrialpes.fr/movi/people/Surname Abstract. In this paper, efficient and generic tools for calibration and 3D reconstruction are presented. These tools exploit geometric con- straints frequently present in man-made environments and allow cam- era calibration as well as scene structure to be estimated with a small amount of user interactions and little a priori knowledge. The proposed approach is based on primitives that naturally characterize rigidity con- straints: parallelepipeds. It has been shown previously that the intrinsic metric characteristics of a parallelepiped are dual to the intrinsic charac- teristics of a perspective camera. Here, we generalize this idea by taking into account additional redundancies between multiple images of multiple parallelepipeds. We propose a method for the estimation of camera and scene parameters that bears strongsimilarities with some self-calibration approaches. Takinginto account prior knowledgeon scene primitives or cameras, leads to simpler equations than for standard self-calibration, and is expected to improve results, as well as to allow structure and mo- tion recovery in situations that are otherwise under-constrained. These principles are illustrated by experimental calibration results and several reconstructions from uncalibrated images. 1 Introduction This paper is about using partial information on camera parameters and scene structure, to simplify and enhance structure from motion and (self-) calibration. We are especially interested in reconstructing man-made environments for which constraints on the scene structure are usually easy to provide. -

Area, Volume and Surface Area

The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project MEASUREMENT AND GEOMETRY Module 11 AREA, VOLUME AND SURFACE AREA A guide for teachers - Years 8–10 June 2011 YEARS 810 Area, Volume and Surface Area (Measurement and Geometry: Module 11) For teachers of Primary and Secondary Mathematics 510 Cover design, Layout design and Typesetting by Claire Ho The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project 2009‑2011 was funded by the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. © The University of Melbourne on behalf of the international Centre of Excellence for Education in Mathematics (ICE‑EM), the education division of the Australian Mathematical Sciences Institute (AMSI), 2010 (except where otherwise indicated). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution‑NonCommercial‑NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by‑nc‑nd/3.0/ The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project MEASUREMENT AND GEOMETRY Module 11 AREA, VOLUME AND SURFACE AREA A guide for teachers - Years 8–10 June 2011 Peter Brown Michael Evans David Hunt Janine McIntosh Bill Pender Jacqui Ramagge YEARS 810 {4} A guide for teachers AREA, VOLUME AND SURFACE AREA ASSUMED KNOWLEDGE • Knowledge of the areas of rectangles, triangles, circles and composite figures. • The definitions of a parallelogram and a rhombus. • Familiarity with the basic properties of parallel lines. • Familiarity with the volume of a rectangular prism. • Basic knowledge of congruence and similarity. • Since some formulas will be involved, the students will need some experience with substitution and also with the distributive law. -

Evaporationin Icparticles

The JapaneseAssociationJapanese Association for Crystal Growth (JACG){JACG) Small Metallic ParticlesProduced by Evaporation in lnert Gas at Low Pressure Size distributions, crystal morphologyand crystal structures KazuoKimoto physiosLaboratory, Department of General Educatien, Nago)ra University Various experimental results ef the studies on fine 1. Introduction particles produced by evaperation and subsequent conden$ation in inert gas at low pressure are reviewed. Small particles of metals and semi-metals can A brief historical survey is given and experimental be produced by evaporation and subsequent arrangements for the production of the particles are condensation in the free space of an inert gas at described. The structure of the stnoke, the qualitative low pressure, a very simple technique, recently particle size clistributions, small particle statistios and "gas often referred to as evaporation technique"i) the crystallographic aspccts ofthe particles are consid- ered in some detail. Emphasis is laid on the crystal (GET). When the pressure of an inert is in the inorphology and the related crystal structures ef the gas range from about one to several tens of Torr, the particles efsome 24 elements. size of the particles produced by GET is in thc range from several to several thousand nm, de- pending on the materials evaporated, the naturc of the inert gas and various other evaporation conditions. One of the most characteristic fea- tures of the particles thus produced is that the particles have, generally speaking, very well- defined crystal habits when the particle size is in the range from about ten to several hundred nm. The crystal morphology and the relevant crystal structures of these particles greatly interested sDme invcstigators in Japan, 4nd encouraged them to study these propenies by means of elec- tron microscopy and electron difliraction. -

Thermodynamics of Spacetime: the Einstein Equation of State

gr-qc/9504004 UMDGR-95-114 Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State Ted Jacobson Department of Physics, University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-4111, USA [email protected] Abstract The Einstein equation is derived from the proportionality of entropy and horizon area together with the fundamental relation δQ = T dS connecting heat, entropy, and temperature. The key idea is to demand that this relation hold for all the local Rindler causal horizons through each spacetime point, with δQ and T interpreted as the energy flux and Unruh temperature seen by an accelerated observer just inside the horizon. This requires that gravitational lensing by matter energy distorts the causal structure of spacetime in just such a way that the Einstein equation holds. Viewed in this way, the Einstein equation is an equation of state. This perspective suggests that it may be no more appropriate to canonically quantize the Einstein equation than it would be to quantize the wave equation for sound in air. arXiv:gr-qc/9504004v2 6 Jun 1995 The four laws of black hole mechanics, which are analogous to those of thermodynamics, were originally derived from the classical Einstein equation[1]. With the discovery of the quantum Hawking radiation[2], it became clear that the analogy is in fact an identity. How did classical General Relativity know that horizon area would turn out to be a form of entropy, and that surface gravity is a temperature? In this letter I will answer that question by turning the logic around and deriving the Einstein equation from the propor- tionality of entropy and horizon area together with the fundamental relation δQ = T dS connecting heat Q, entropy S, and temperature T . -

Crystallography Ll Lattice N-Dimensional, Infinite, Periodic Array of Points, Each of Which Has Identical Surroundings

crystallography ll Lattice n-dimensional, infinite, periodic array of points, each of which has identical surroundings. use this as test for lattice points A2 ("bcc") structure lattice points Lattice n-dimensional, infinite, periodic array of points, each of which has identical surroundings. use this as test for lattice points CsCl structure lattice points Choosing unit cells in a lattice Want very small unit cell - least complicated, fewer atoms Prefer cell with 90° or 120°angles - visualization & geometrical calculations easier Choose cell which reflects symmetry of lattice & crystal structure Choosing unit cells in a lattice Sometimes, a good unit cell has more than one lattice point 2-D example: Primitive cell (one lattice pt./cell) has End-centered cell (two strange angle lattice pts./cell) has 90° angle Choosing unit cells in a lattice Sometimes, a good unit cell has more than one lattice point 3-D example: body-centered cubic (bcc, or I cubic) (two lattice pts./cell) The primitive unit cell is not a cube 14 Bravais lattices Allowed centering types: P I F C primitive body-centered face-centered C end-centered Primitive R - rhombohedral rhombohedral cell (trigonal) centering of trigonal cell 14 Bravais lattices Combine P, I, F, C (A, B), R centering with 7 crystal systems Some combinations don't work, some don't give new lattices - C tetragonal C-centering destroys cubic = P tetragonal symmetry 14 Bravais lattices Only 14 possible (Bravais, 1848) System Allowed centering Triclinic P (primitive) Monoclinic P, I (innerzentiert) Orthorhombic P, I, F (flächenzentiert), A (end centered) Tetragonal P, I Cubic P, I, F Hexagonal P Trigonal P, R (rhombohedral centered) Choosing unit cells in a lattice Unit cell shape must be: 2-D - parallelogram (4 sides) 3-D - parallelepiped (6 faces) Not a unit cell: Choosing unit cells in a lattice Unit cell shape must be: 2-D - parallelogram (4 sides) 3-D - parallelepiped (6 faces) Not a unit cell: correct cell Stereographic projections Show or represent 3-D object in 2-D Procedure: 1. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

Cross Product Review

12.4 Cross Product Review: The dot product of uuuu123, , and v vvv 123, , is u v uvuvuv 112233 uv u u u u v u v cos or cos uv u and v are orthogonal if and only if u v 0 u uv uv compvu projvuv v v vv projvu cross product u v uv23 uv 32 i uv 13 uv 31 j uv 12 uv 21 k u v is orthogonal to both u and v. u v u v sin Geometric description of the cross product of the vectors u and v The cross product of two vectors is a vector! • u x v is perpendicular to u and v • The length of u x v is u v u v sin • The direction is given by the right hand side rule Right hand rule Place your 4 fingers in the direction of the first vector, curl them in the direction of the second vector, Your thumb will point in the direction of the cross product Algebraic description of the cross product of the vectors u and v The cross product of uu1, u 2 , u 3 and v v 1, v 2 , v 3 is uv uv23 uvuv 3231,, uvuv 1312 uv 21 check (u v ) u 0 and ( u v ) v 0 (u v ) u uv23 uvuv 3231 , uvuv 1312 , uv 21 uuu 123 , , uvu231 uvu 321 uvu 312 uvu 132 uvu 123 uvu 213 0 similary: (u v ) v 0 length u v u v sin is a little messier : 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2uv 2 2 2 uvuv sin22 uv 1 cos uv 1 uvuv 22 uv now need to show that u v2 u 2 v 2 u v2 (try it..) An easier way to remember the formula for the cross products is in terms of determinants: ab 12 2x2 determinant: ad bc 4 6 2 cd 34 3x3 determinants: An example Copy 1st 2 columns 1 6 2 sum of sum of 1 6 2 1 6 forward backward 3 1 3 3 1 3 3 1 diagonal diagonal 4 5 2 4 5 2 4 5 products products determinant = 2 72 30 8 15 36 40 59 19 recall: uv uv23 uvuv 3231, uvuv 1312 , uv 21 i j k i j k i j u1 u 2 u 3 u 1 u 2 now we claim that uvu1 u 2 u 3 v1 v 2 v 3 v 1 v 2 v1 v 2 v 3 iuv23 j uv 31 k uv 12 k uv 21 i uv 32 j uv 13 u v uv23 uv 32 i uv 13 uv 31 j uv 12 uv 21 k uv uv23 uvuv 3231,, uvuv 1312 uv 21 Example: Let u1, 2,1 and v 3,1, 2 Find u v. -

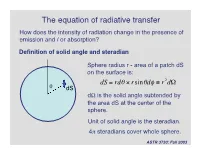

The Equation of Radiative Transfer How Does the Intensity of Radiation Change in the Presence of Emission and / Or Absorption?

The equation of radiative transfer How does the intensity of radiation change in the presence of emission and / or absorption? Definition of solid angle and steradian Sphere radius r - area of a patch dS on the surface is: dS = rdq ¥ rsinqdf ≡ r2dW q dS dW is the solid angle subtended by the area dS at the center of the † sphere. Unit of solid angle is the steradian. 4p steradians cover whole sphere. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Definition of the specific intensity Construct an area dA normal to a light ray, and consider all the rays that pass through dA whose directions lie within a small solid angle dW. Solid angle dW dA The amount of energy passing through dA and into dW in time dt in frequency range dn is: dE = In dAdtdndW Specific intensity of the radiation. † ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Compare with definition of the flux: specific intensity is very similar except it depends upon direction and frequency as well as location. Units of specific intensity are: erg s-1 cm-2 Hz-1 steradian-1 Same as Fn Another, more intuitive name for the specific intensity is brightness. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Simple relation between the flux and the specific intensity: Consider a small area dA, with light rays passing through it at all angles to the normal to the surface n: n o In If q = 90 , then light rays in that direction contribute zero net flux through area dA. q For rays at angle q, foreshortening reduces the effective area by a factor of cos(q). -

Area of Polygons and Complex Figures

Geometry AREA OF POLYGONS AND COMPLEX FIGURES Area is the number of non-overlapping square units needed to cover the interior region of a two- dimensional figure or the surface area of a three-dimensional figure. For example, area is the region that is covered by floor tile (two-dimensional) or paint on a box or a ball (three- dimensional). For additional information about specific shapes, see the boxes below. For additional general information, see the Math Notes box in Lesson 1.1.2 of the Core Connections, Course 2 text. For additional examples and practice, see the Core Connections, Course 2 Checkpoint 1 materials or the Core Connections, Course 3 Checkpoint 4 materials. AREA OF A RECTANGLE To find the area of a rectangle, follow the steps below. 1. Identify the base. 2. Identify the height. 3. Multiply the base times the height to find the area in square units: A = bh. A square is a rectangle in which the base and height are of equal length. Find the area of a square by multiplying the base times itself: A = b2. Example base = 8 units 4 32 square units height = 4 units 8 A = 8 · 4 = 32 square units Parent Guide with Extra Practice 135 Problems Find the areas of the rectangles (figures 1-8) and squares (figures 9-12) below. 1. 2. 3. 4. 2 mi 5 cm 8 m 4 mi 7 in. 6 cm 3 in. 2 m 5. 6. 7. 8. 3 units 6.8 cm 5.5 miles 2 miles 8.7 units 7.25 miles 3.5 cm 2.2 miles 9. -

Right Triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem Related?

Activity Assess 9-6 EXPLORE & REASON Right Triangles and Consider △ ABC with altitude CD‾ as shown. the Pythagorean B Theorem D PearsonRealize.com A 45 C 5√2 I CAN… prove the Pythagorean Theorem using A. What is the area of △ ABC? Of △ACD? Explain your answers. similarity and establish the relationships in special right B. Find the lengths of AD‾ and AB‾ . triangles. C. Look for Relationships Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ ABC VOCABULARY by the length of one of its sides. Divide the length of the hypotenuse of △ACD by the length of one of its sides. Make a conjecture that explains • Pythagorean triple the results. ESSENTIAL QUESTION How are similarity in right triangles and the Pythagorean Theorem related? Remember that the Pythagorean Theorem and its converse describe how the side lengths of right triangles are related. THEOREM 9-8 Pythagorean Theorem If a triangle is a right triangle, If... △ABC is a right triangle. then the sum of the squares of the B lengths of the legs is equal to the square of the length of the hypotenuse. c a A C b 2 2 2 PROOF: SEE EXAMPLE 1. Then... a + b = c THEOREM 9-9 Converse of the Pythagorean Theorem 2 2 2 If the sum of the squares of the If... a + b = c lengths of two sides of a triangle is B equal to the square of the length of the third side, then the triangle is a right triangle. c a A C b PROOF: SEE EXERCISE 17. Then... △ABC is a right triangle. -

Calculus Formulas and Theorems

Formulas and Theorems for Reference I. Tbigonometric Formulas l. sin2d+c,cis2d:1 sec2d l*cot20:<:sc:20 +.I sin(-d) : -sitt0 t,rs(-//) = t r1sl/ : -tallH 7. sin(A* B) :sitrAcosB*silBcosA 8. : siri A cos B - siu B <:os,;l 9. cos(A+ B) - cos,4cos B - siuA siriB 10. cos(A- B) : cosA cosB + silrA sirrB 11. 2 sirrd t:osd 12. <'os20- coS2(i - siu20 : 2<'os2o - I - 1 - 2sin20 I 13. tan d : <.rft0 (:ost/ I 14. <:ol0 : sirrd tattH 1 15. (:OS I/ 1 16. cscd - ri" 6i /F tl r(. cos[I ^ -el : sitt d \l 18. -01 : COSA 215 216 Formulas and Theorems II. Differentiation Formulas !(r") - trr:"-1 Q,:I' ]tra-fg'+gf' gJ'-,f g' - * (i) ,l' ,I - (tt(.r))9'(.,') ,i;.[tyt.rt) l'' d, \ (sttt rrJ .* ('oqI' .7, tJ, \ . ./ stll lr dr. l('os J { 1a,,,t,:r) - .,' o.t "11'2 1(<,ot.r') - (,.(,2.r' Q:T rl , (sc'c:.r'J: sPl'.r tall 11 ,7, d, - (<:s<t.r,; - (ls(].]'(rot;.r fr("'),t -.'' ,1 - fr(u") o,'ltrc ,l ,, 1 ' tlll ri - (l.t' .f d,^ --: I -iAl'CSllLl'l t!.r' J1 - rz 1(Arcsi' r) : oT Il12 Formulas and Theorems 2I7 III. Integration Formulas 1. ,f "or:artC 2. [\0,-trrlrl *(' .t "r 3. [,' ,t.,: r^x| (' ,I 4. In' a,,: lL , ,' .l 111Q 5. In., a.r: .rhr.r' .r r (' ,l f 6. sirr.r d.r' - ( os.r'-t C ./ 7. /.,,.r' dr : sitr.i'| (' .t 8. tl:r:hr sec,rl+ C or ln Jccrsrl+ C ,f'r^rr f 9. -

15 BASIC PROPERTIES of CONVEX POLYTOPES Martin Henk, J¨Urgenrichter-Gebert, and G¨Unterm

15 BASIC PROPERTIES OF CONVEX POLYTOPES Martin Henk, J¨urgenRichter-Gebert, and G¨unterM. Ziegler INTRODUCTION Convex polytopes are fundamental geometric objects that have been investigated since antiquity. The beauty of their theory is nowadays complemented by their im- portance for many other mathematical subjects, ranging from integration theory, algebraic topology, and algebraic geometry to linear and combinatorial optimiza- tion. In this chapter we try to give a short introduction, provide a sketch of \what polytopes look like" and \how they behave," with many explicit examples, and briefly state some main results (where further details are given in subsequent chap- ters of this Handbook). We concentrate on two main topics: • Combinatorial properties: faces (vertices, edges, . , facets) of polytopes and their relations, with special treatments of the classes of low-dimensional poly- topes and of polytopes \with few vertices;" • Geometric properties: volume and surface area, mixed volumes, and quer- massintegrals, including explicit formulas for the cases of the regular simplices, cubes, and cross-polytopes. We refer to Gr¨unbaum [Gr¨u67]for a comprehensive view of polytope theory, and to Ziegler [Zie95] respectively to Gruber [Gru07] and Schneider [Sch14] for detailed treatments of the combinatorial and of the convex geometric aspects of polytope theory. 15.1 COMBINATORIAL STRUCTURE GLOSSARY d V-polytope: The convex hull of a finite set X = fx1; : : : ; xng of points in R , n n X i X P = conv(X) := λix λ1; : : : ; λn ≥ 0; λi = 1 : i=1 i=1 H-polytope: The solution set of a finite system of linear inequalities, d T P = P (A; b) := x 2 R j ai x ≤ bi for 1 ≤ i ≤ m ; with the extra condition that the set of solutions is bounded, that is, such that m×d there is a constant N such that jjxjj ≤ N holds for all x 2 P .