Examining the Underlying Science and Impacts of Glider Truck Regulations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix E Descriptions of Glider Vehicles by Industry Participants

Comment on EPA Proposed Glider Vehicles Rule, Docket ID EPA-HQ-OAR-2014-0827, submitted January 5, 2018 Appendix E Descriptions of Glider Vehicles by Industry Participants Description of Glider Vehicles by Glider Manufacturer Fitzgerald Glider Kits, “What is a Glider Kit” https://www.fitzgeraldgliderkits.com/what-is-a-glider-kit (accessed Jan. 3, 2018) Description of Glider Vehicles by Glider Manufacturer Harrison Truck Centers, “Glider Kits” http://www.htctrucks.com/index.php/sales-1/harrison-truck-centers- glider-kits (accessed Jan. 3, 2018) Description of Glider Vehicles by Glider Manufacturer Freightliner, “Glider: The Truck You Always Wanted” Brochure www.dtnaglider.com THE TRUCK YOU ALWayS WaNTED WHICH ONE IS THE GLIDER? IT’S HARD TO TELL Rolling down the road, it’s difficult to spot any differences between a Freightliner Glider and a new Freightliner truck. A Glider kit comes to you as a brand-new, complete assembly that includes the frame, cab, steer axle and wheels, plus a long list of standard equipment. Every Glider also comes with a loose parts box containing up to 160 parts — everything you need to get rolling. YOU PROVIDE WE PROVIDE COMPLETE ASSEMBLY 1 THE NEXT BEST THING TO A NEW TRUCK Designed, engineered and assembled alongside new Freightliner trucks, a Glider gives you everything a new truck offers except for two of the three main driveline components (engine, transmission and rear axle). You can either recapitalize any of these from your existing unit, or spec a factory-installed remanufactured engine or rear axle. BACKED BY A NEW TRUCK WARRANTY Unlike a used truck, every factory-installed component on a Glider is covered by Freightliner’s Warranty. -

A Comprehensive Study of Key Electric Vehicle (EV) Components, Technologies, Challenges, Impacts, and Future Direction of Development

Review A Comprehensive Study of Key Electric Vehicle (EV) Components, Technologies, Challenges, Impacts, and Future Direction of Development Fuad Un-Noor 1, Sanjeevikumar Padmanaban 2,*, Lucian Mihet-Popa 3, Mohammad Nurunnabi Mollah 1 and Eklas Hossain 4,* 1 Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Khulna University of Engineering and Technology, Khulna 9203, Bangladesh; [email protected] (F.U.-N.); [email protected] (M.N.M.) 2 Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, University of Johannesburg, Auckland Park 2006, South Africa 3 Faculty of Engineering, Østfold University College, Kobberslagerstredet 5, 1671 Kråkeroy-Fredrikstad, Norway; [email protected] 4 Department of Electrical Engineering & Renewable Energy, Oregon Tech, Klamath Falls, OR 97601, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (E.H.); Tel.: +27-79-219-9845 (S.P.); +1-541-885-1516 (E.H.) Academic Editor: Sergio Saponara Received: 8 May 2017; Accepted: 21 July 2017; Published: 17 August 2017 Abstract: Electric vehicles (EV), including Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV), Hybrid Electric Vehicle (HEV), Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV), Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle (FCEV), are becoming more commonplace in the transportation sector in recent times. As the present trend suggests, this mode of transport is likely to replace internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles in the near future. Each of the main EV components has a number of technologies that are currently in use or can become prominent in the future. EVs can cause significant impacts on the environment, power system, and other related sectors. The present power system could face huge instabilities with enough EV penetration, but with proper management and coordination, EVs can be turned into a major contributor to the successful implementation of the smart grid concept. -

Mid-Atlantic and Northeast Plug-In Electric Vehicle Cost-Benefit Analysis Methodology & Assumptions

Mid-Atlantic and Northeast Plug-in Electric Vehicle Cost-Benefit Analysis Methodology & Assumptions December 2016 Acknowledgements Authors: Dana Lowell, Brian Jones, and David Seamonds M.J. Bradley & Associates LLC Prepared by: M.J. Bradley & Associates LLC 47 Junction Square Drive Concord, MA 01742 Contact: Dana Lowell (978) 405-1275 [email protected] For Submission to: Natural Resources Defense Council 40 W 20th Street, New York, NY 10011 Contact: Luke Tonachel (212) 727-4607 [email protected] About M.J. Bradley & Associates LLC M.J. Bradley & Associates LLC (MJB&A) provides strategic and technical advisory services to address critical energy and environmental matters including: energy policy, regulatory compliance, emission markets, energy efficiency, renewable energy, and advanced technologies. Our multi-national client base includes electric and natural gas utilities, major transportation fleet operators, clean technology firms, environmental groups and government agencies. We bring insights to executives, operating managers, and advocates. We help you find opportunity in environmental markets, anticipate and respond smartly to changes in administrative law and policy at federal and state levels. We emphasize both vision and implementation, and offer timely access to information along with ideas for using it to the best advantage. © M.J. Bradley & Associates 2016 December 2016 Mid-Atlantic and Northeast Plug-in Electric Vehicle Cost-Benefit Analysis Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... -

1 Minimum Glider Truck Specifications for One (1

MINIMUM GLIDER TRUCK SPECIFICATIONS FOR ONE (1) 2016 TANDEM AXLE CONVENTIONAL CAB & CHASSIS 53,000 L.B. GVW MINIMUM 6 X 4 WHEEL BASE------- 212” Maximum – Set forward front axle OVERHANG---------- 65” from centerline of tandem axles to end of rear frame 24” front overhang BEFORE CAB TO AXLE (B.B.C.) ------------------ 110” Minimum ENGINE--------------- PrepKit C15-435-550 ELEC98 EPA CARB TRANSMISSION---- Automatic - PrepKit for Allison HD4560P RDS Generation 3 Controller AXLES------------------ Front 20,000 Lb. Rated capacity Rear 46,000 Lb. Rated capacity Pump Type Differential GEAR RATIO--------- Gear Ratio 4.88 DIFFERENTIAL------ Locking Power Divider, Divider Controlled Full Locking Mains Differential, Pump Type Lubrication REAR SUSPENSION- Neway AD246 Air Ride 54” TT or Equivalent Level valve with dash-mounted pressure gauge SPRINGS---------------- Axle capacity or more. State capacity. Capacity must be appropriate to meet GVW STEERING------------- Dual power. State make & model. Tilt wheel BRAKES---------------- Full Air S Cam with Auto Slack Adjusters – Gunite AIR COMPRESSOR- Tank inside frame, spin on air drier cartridge, mounted on outside of frame with guard, low pressure warning device and pressure gauge 1 RADIATOR------------ The radiator must have an opening for a front mounted hydraulic Pump with a minimum 4” clearance from center of crank shaft Hub. The fan must clear the drive shaft for a hydraulic pump ELECTRICAL--------- 12 Volt Electrical System with a battery box to hold four (4) Heavy Duty 12 volt batteries, mounted -

SAB Testimony ICCT V2

1225 I Street NW Suite 900 Washington DC 20005 +1 202.534.1600 www.theicct.org Testimony of Rachel Muncrief and John German on behalf of the International Council on Clean Transportation Before the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Science Advisory Board May 31, 2018 Washington Plaza Hotel, 10 Thomas Cir NW, Washington, DC A. Oral Testimony My name is Rachel Muncrief, and I direct the heavy-duty vehicles program and compliance and enforcement program of the International Council on Clean Transportation. I have a PhD in Chemical Engineering and have been working on vehicle emissions and efficiency policy in the United States for 15 years — 5 years at the ICCT and 10 years at the University of Houston, concluding my time in Houston as a research faculty and director of the university's diesel vehicle testing and research lab. John German is a Senior Fellow at ICCT, with primary focus on vehicle policy and powertrain technology. He started working on these issues in 1976 in response to the original CAFE standards, addressing these issues for about a decade each for Chrysler, EPA, Honda, and ICCT. Thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I would like to briefly address a few key technical issues raised in the SAB workgroup memo from May 18, 2018 concerning the 2025 light-duty vehicles GHG standards and the emission requirements for glider vehicles. We would like to state up front that we fully support the workgroup’s recommendations to move forward with an SAB review of these proposed actions. On the 2025 GHG standards: The agencies’ 2016 Technical Assessment updated their analyses, but still failed to consider a number of technology advances that are already in production or close to production, overestimated the cost of other technologies, and ignored benefits from features associated with efficiency technology that are desired by consumers. -

Arizona Mayors' Letter of Support

July 13th, 2021 The Honorable Kyrsten Sinema The Honorable Mark Kelly United States Senate United States Senate The Honorable Tom O’Halleran The Honorable Ann Kirkpatrick United State Congress United States Congress The Honorable Raúl M. Grijalva The Honorable Paul Gosar United States Congress United States Congress The Honorable Andy Biggs The Honorable David Schweikert United States Congress United States Congress The Honorable Ruben Gallego The Honorable Debbie Lesko United States Congress United States Congress The Honorable Greg Stanton United States Congress Dear Members of the Arizona Congressional Delegation: As Mayors of cities and towns located along the potential Tucson-Phoenix-West Valley Amtrak route, we enthusiastically support Amtrak’s vision to bring passenger rail service to our communities. Frequent and reliable passenger rail service will expand economic opportunities and provide important regional connections between our cities and towns. We further support Amtrak’s reauthorization proposal to create a Corridor Development Program, which will help advance Amtrak’s planning, development and implementation of new corridor routes and improvements to existing routes. By funding this program through Amtrak’s National Network grant, Amtrak can make the initial capital investments necessary to get these new routes up and running. The grant will also cover the operating costs for the first several years, offering new services the ability to grow ridership and generate revenue. Amtrak has made clear its commitment to working in a collaborative manner with state and local partners to grow the national rail network, and we look forward to this partnership. In addition to Amtrak’s National Network grant, we also support increased funding for USDOT competitive grants, which can also support more passenger rail. -

Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicle Value Proposition Study

DOCUMENT AVAILABILITY Reports produced after January 1, 1996, are generally available free via the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Information Bridge: Web site: http://www.osti.gov/bridge Reports produced before January 1, 1996, may be purchased by members of the public from the following source: National Technical Information Service 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 Telephone: 703-605-6000 (1-800-553-6847) TDD: 703-487-4639 Fax: 703-605-6900 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.ntis.gov/support/ordernowabout.htm Reports are available to DOE employees, DOE contractors, Energy Technology Data Exchange (ETDE) representatives, and International Nuclear Information System (INIS) representatives from the following source: Office of Scientific and Technical Information P.O. Box 62 Oak Ridge, TN 37831 Telephone: 865-576-8401 Fax: 865-576-5728 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.osti.gov/contact.html This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. -

State Delegations

STATE DELEGATIONS Number before names designates Congressional district. Senate Republicans in roman; Senate Democrats in italic; Senate Independents in SMALL CAPS; House Democrats in roman; House Republicans in italic; House Libertarians in SMALL CAPS; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface. ALABAMA SENATORS 3. Mike Rogers Richard C. Shelby 4. Robert B. Aderholt Doug Jones 5. Mo Brooks REPRESENTATIVES 6. Gary J. Palmer [Democrat 1, Republicans 6] 7. Terri A. Sewell 1. Bradley Byrne 2. Martha Roby ALASKA SENATORS REPRESENTATIVE Lisa Murkowski [Republican 1] Dan Sullivan At Large – Don Young ARIZONA SENATORS 3. Rau´l M. Grijalva Kyrsten Sinema 4. Paul A. Gosar Martha McSally 5. Andy Biggs REPRESENTATIVES 6. David Schweikert [Democrats 5, Republicans 4] 7. Ruben Gallego 1. Tom O’Halleran 8. Debbie Lesko 2. Ann Kirkpatrick 9. Greg Stanton ARKANSAS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES John Boozman [Republicans 4] Tom Cotton 1. Eric A. ‘‘Rick’’ Crawford 2. J. French Hill 3. Steve Womack 4. Bruce Westerman CALIFORNIA SENATORS 1. Doug LaMalfa Dianne Feinstein 2. Jared Huffman Kamala D. Harris 3. John Garamendi 4. Tom McClintock REPRESENTATIVES 5. Mike Thompson [Democrats 45, Republicans 7, 6. Doris O. Matsui Vacant 1] 7. Ami Bera 309 310 Congressional Directory 8. Paul Cook 31. Pete Aguilar 9. Jerry McNerney 32. Grace F. Napolitano 10. Josh Harder 33. Ted Lieu 11. Mark DeSaulnier 34. Jimmy Gomez 12. Nancy Pelosi 35. Norma J. Torres 13. Barbara Lee 36. Raul Ruiz 14. Jackie Speier 37. Karen Bass 15. Eric Swalwell 38. Linda T. Sa´nchez 16. Jim Costa 39. Gilbert Ray Cisneros, Jr. 17. Ro Khanna 40. Lucille Roybal-Allard 18. -

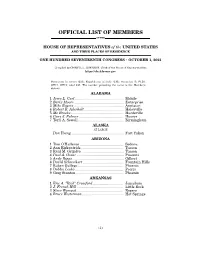

Official List of Members by State

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS • OCTOBER 1, 2021 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives https://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (220); Republicans in italic (212); vacancies (3) FL20, OH11, OH15; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Jerry L. Carl ................................................ Mobile 2 Barry Moore ................................................. Enterprise 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................. Phoenix 8 Debbie Lesko ............................................... -

Federal Register/Vol. 76, No. 104/Tuesday, May 31, 2011/Notices

31354 Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 104 / Tuesday, May 31, 2011 / Notices Estimated time per Response: 5 assembled in the United States from body, axles, and wheels. The TCE is then minutes. parts made in the United States, Turkey, assembled in the U.S. from both imported Estimated Total Annual Burden Switzerland, Hungary, Japan, Germany, and U.S.-origin components. Hours: 35,939. Canada, the United Kingdom, and A Bill of Materials was submitted with the request. Apart from the glider, parts for the Dated: May 24, 2011. various other countries is substantially TCE are also imported from Switzerland, Tracey Denning, transformed in the United States, such Hungary, Japan, Germany, Canada, the that the United States is the country of Agency Clearance Officer, U.S. Customs and United Kingdom, and various other Border Protection. origin of the finished article for countries. According to the submission, the purposes of U.S. Government TCE vehicle is composed of 31 components, [FR Doc. 2011–13302 Filed 5–27–11; 8:45 am] procurement. of which 14 are of U.S.-origin. For purposes BILLING CODE 9111–14–P Section 177.29, Customs Regulations of this decision, we assume that the (19 CFR 177.29), provides that notice of components of U.S. origin are produced in final determinations shall be published the U.S. or are substantially transformed in DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND the U.S. and considered products of the U.S. SECURITY in the Federal Register within 60 days The U.S. assembly occurs at various of the date the final determination is stations. -

ARIZONA FAH MEMBER FACILITIES Federation of American Hospitals Represents America’S Tax-Paying Community Hospitals and SENATE Health Systems

ARIZONA FAH MEMBER FACILITIES Federation of American Hospitals represents America’s tax-paying community hospitals and SENATE health systems. Sen. Mark Kelly (D) Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D) HOUSE (Click name to view the district) Rep. Tom O’Halleran (D) / Arizona 1st Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick (D) / Arizona 2nd Rep. Raúl Grijalva (D) / Arizona 3rd Rep. Paul Gosar (R) / Arizona 4th Rep. Andy Biggs (R) / Arizona 5th Rep. David Schweikert (R) / Arizona 6th TOTAL Rep. Ruben Gallego (D) / Arizona 7th FACILITIES Rep. Debbie Lesko (R) / Arizona 8th Rep. Greg Stanton (D) / Arizona 9th 25 TOTAL HOSPITAL BEDS 3,482 TOTAL EMPLOYEES 13,145 FEDERATION OF AMERICAN HOSPITALS® 750 9th Street, N.W. Suite 600, Washington, DC 20001 fah.org ARIZONA FAH MEMBER FACILITIES Beds Employees REP. TOM O'HALLERAN (D) / ARIZONA 1ST 1 HOSPITAL Oro Valley Hospital Oro Valley Community Health Systems 144 612 REP. ANN KIRKPATRICK (D) / ARIZONA 2ND 6 HOSPITALS Canyon Vista Medical Center Sierra Vista LifePoint Health 100 779 Carondelet St. Joseph’s Hospital Tucson Tenet Healthcare Corporation 486 1,451 Encompass Health Rehabilitation Hospital of Northwest Tucson Encompass Health 60 171 Tucson Encompass Health Rehabilitation Institute of Tucson Tucson Encompass Health 80 241 Northwest Medical Center Tucson Community Health Systems 300 1,696 Palo Verde Hospital Tucson Universal Health Services, Inc. 84 200 REP. RAÚL GRIJALVA (D) / ARIZONA 3RD 3 HOSPITALS Carondelet Holy Cross Hospital Nogales Tenet Healthcare Corporation 25 174 Carondelet St. Mary’s Hospital Tucson Tenet Healthcare Corporation 400 1,407 Yuma Rehabilitation Hospital, a Partnership of Encompass Yuma Encompass Health 51 163 Health & YRMC REP. -

Zero Emissions Trucks

Zero emissions trucks An overview of state-of-the-art technologies and their potential Report Delft, July 2013 Author(s): Eelco den Boer (CE Delft) Sanne Aarnink (CE Delft) Florian Kleiner (DLR) Johannes Pagenkopf (DLR) Publication Data Bibliographical data: Eelco den Boer (CE Delft), Sanne Aarnink (CE Delft), Florian Kleiner (DLR), Johannes Pagenkopf (DLR) Zero emissions trucks An overview of state-of-the-art technologies and their potential Delft, CE Delft, July 2013 Publication code: 13.4841.21 CE publications are available from www.cedelft.eu Commissioned by: The International Council for Clean Transportation (ICCT). Further information on this study can be obtained from the contact person, Eelco den Boer. © copyright, CE Delft, Delft CE Delft Committed to the Environment CE Delft is an independent research and consultancy organisation specialised in developing structural and innovative solutions to environmental problems. CE Delft’s solutions are characterised in being politically feasible, technologically sound, economically prudent and socially equitable. Subcontractor information German Aerospace Center Institute of Vehicle Concepts Prof. Dr. Ing. H.E. Friedrich Pfaffenwaldring 38-40 D-70569 Stuttgart, Germany http://www.dlr.de 2 July 2013 4.841.1 – Zero emissions trucks Preface This report has been developed to contribute to the discussion on future road freight transport and the role on non-conventional drivetrains. The primary objective of the report is to assess zero emission drivetrain technologies for on-road heavy-duty freight vehicles. More specifically, their CO2 reduction potential, the state of these technologies, their expected costs in case of a technology shift, the role of policies to promote these technologies, and greenhouse reduction scenarios for the European Union have been studied.