William Blake and Popular Religious Imagery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issues) and Begin (Cambridge UP, 1995), Has Recently Retired from Mcgill with the Summer Issue

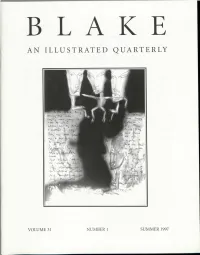

AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY VOLUME 31 NUMBER 1 SUMMER 1997 s-Sola/ce AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY VOLUME 31 NUMBER 1 SUMMER 1997 CONTENTS Articles Angela Esterhammer, Creating States: Studies in the Performative Language of John Milton Blake, Wollstonecraft, and the and William Blake Inconsistency of Oothoon Reviewed by David L. Clark 24 by Wes Chapman 4 Andrew Lincoln, Spiritual History: A Reading of Not from Troy, But Jerusalem: Blake's William Blake's Vala, or The Four Zoas Canon Revision Reviewed by John B. Pierce 29 by R. Paul Yoder \7 20/20 Blake, written and directed by George Coates Lorenz Becher: An Artist in Berne, Reviewed by James McKusick 35 Switzerland by Lorenz Becher 22 Correction Reviews Deborah McCollister 39 Frank Vaughan, Again to the Life of Eternity: William Blake's Illustrations to the Poems of Newsletter Thomas Gray Tyger and ()//;<•/ Tales, Blake Society Web Site, Reviewed by Christopher Heppner 24 Blake Society Program for 1997 39 CONTRIBUTORS Morton D. Paley, Department of English, University of Cali• fornia, Berkeley CA 94720-1030 Email: [email protected] LORENZ BECHER lives and works in Berne, Switzerland as artist, English teacher, and househusband. G. E. Bentley, Jr., 246 MacPherson Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M4V 1A2. The University of Toronto declines to forward mail. WES CHAPMAN teaches in the Department of English at Illi• nois Wesleyan University. He has published a study of gen• Nelson Hilton, Department of English, University of Geor• der anxiety in Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow and gia, Athens, GA 30602 has a hypertext fiction and a hypertext poem forthcoming Email: [email protected] from Eastgate Systems. -

Introduction

Introduction The notes which follow are intended for study and revision of a selection of Blake's poems. About the poet William Blake was born on 28 November 1757, and died on 12 August 1827. He spent his life largely in London, save for the years 1800 to 1803, when he lived in a cottage at Felpham, near the seaside town of Bognor, in Sussex. In 1767 he began to attend Henry Pars's drawing school in the Strand. At the age of fifteen, Blake was apprenticed to an engraver, making plates from which pictures for books were printed. He later went to the Royal Academy, and at 22, he was employed as an engraver to a bookseller and publisher. When he was nearly 25, Blake married Catherine Bouchier. They had no children but were happily married for almost 45 years. In 1784, a year after he published his first volume of poems, Blake set up his own engraving business. Many of Blake's best poems are found in two collections: Songs of Innocence (1789) to which was added, in 1794, the Songs of Experience (unlike the earlier work, never published on its own). The complete 1794 collection was called Songs of Innocence and Experience Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul. Broadly speaking the collections look at human nature and society in optimistic and pessimistic terms, respectively - and Blake thinks that you need both sides to see the whole truth. Blake had very firm ideas about how his poems should appear. Although spelling was not as standardised in print as it is today, Blake was writing some time after the publication of Dr. -

Eibeibunka 47

1 『英米文化』47, 1–12 (2017) ISSN: 0917–3536 The Unity of Contraries in William Blake’s World of Vegetation NAKAYAMA Fumi Abstract William Blake, English-romantic poet and copperplate engraving artist, often compares human to vegetable organism in his late prophetic books. This paper is an attempt to ana- lyze the unity of ‘contraries’ through the association between Blake’s world of vegetation and the Bible, especially, The Book of the Prophet Ezekiel. First, I trace the sources of inspi- ration for Blake in Celtic culture, Christianity and philosophy. And next, I discuss the unity of contraries into ‘the Poetic Genius’ as Blake’s dialectic in his world of vegetation. Around the time when Blake wrote “To the Muses” in his first work, Poetical Sketches, muses were the very existence of scholarship. But gradually his confidence in muses began to waver. Muses are the daughters of ‘Mnemosyne’ and so Blake regarded the works inspired by muses as not exactly a good art. For Blake, ‘the Poetic Genius’ is the most important existence. As for the common terms between Blake’s prophecy and The Book of Ezekiel, I deal with two specific examples, the analogy of human likened to vegetable and ‘four.’ Both also have the similar plot, the division and unity of the personified ‘Jerusalem,’ and the process in which Jerusalem went to ruin, and later it was rebuilt as a theocracy. 1. Introduction William Blake (1757–1827) is an English-romantic poet and copperplate engraving artist, and in his works, human is often compared to vegetable organism. This imagery is read par- ticularly in his late prophetic books, The Four Zoas (1795–1804), Milton (1804–08) and Jerusalem (1804–20). -

William Blake's Role As English Prophet Michelle Lynn Jackson Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Honors Theses University Honors Program 5-2004 The oiceV of One Crying in a Wilderness of Error: William Blake's Role as English Prophet Michelle Lynn Jackson Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/uhp_theses Recommended Citation Jackson, Michelle Lynn, "The oV ice of One Crying in a Wilderness of Error: William Blake's Role as English Prophet" (2004). Honors Theses. Paper 140. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I I The Voice of One Crying in a Wilderness of Brror: I William Blake's Role as Bnglish Prophet I I I I I Michelle L. Jackson I I I I I I I A thesis presented in fulfillment of the University Honors I Graduation Option at Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 7, 2004 I I I 1 I The Voice of One Crying in a Wilderness of Error: William Blake's Role as English Prophet I William Blake's radically revisionist perception of the I Bible led him to denounce orthodox religion. For Blake, the I ancient prophets were nothing less than masters of Poetic Genius and believed their unadulterated imaginative visions, not the I rigid rules of orthodoxy, to be the true source of religion. To I save the Poetic Genius conceptually from the abuse of established religion, Blake formulated his theory of Contraries, I which unites ftHeaven" and ftHell," human Reason and Energy. -

Night Thoughts

DISCUSSION A Re-View of Some Problems in Understanding Blake’s Night Thoughts John E. Grant Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 18, Issue 3, Winter 1984-85, pp. 155- 181 PAGE 155 WINTER 1984-85 BLAKE/AS ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY prehensive project which seeks to explain and restore an but does not, however, achieve it. historical methodology to literary studies" (ix). Much of The Romantic Ideology, in fact, reads like an introduction reliant on generalizations that one hopes the author will 1 substantiate and perhaps qualify. I say this not to dismiss All of these critics, like McGann, regard Natural Superna- turalism as a canonical text. In "Rationality and Imagination in the book, only to indicate its limits. I sympathize with Cultural History," Critical Inquiry, 2 (Spring, 1976), 447-64—a McGann's desire to restore historical self-consciousness discussion of Natural Supernaturalism that McGann should acknowl- to Romantic scholarship and, more generally, to aca- edge—Abrams answers some of these critics and defends his omis- demic criticism. The Romantic Ideology affirms this goal sion of Byron. the proper forum for detailed discussion of several points I shall raise. Furthermore, some of the issues I shall DISCUSSION address extend beyond the specific problems of the Clar- with intellectual spears SLIODQ winged arrows of thought endon edition of Night Thoughts to larger questions of how Blake's visual works can be presented and under- stood. This re-view of the Clarendon edition should make it easier for readers to use the edition in ways that A Re-View of Some Problems in will advance scholarship on Blake's most extensive proj- ect of pictorial criticism. -

William Blake ( 1757-1827)

William Blake ( 1757-1827) "And I made a rural pen, " "0 Earth. 0 Earth, returnl And I stained the water clear, "Arise from out the dewy grass. And J wrote my happy songs "Night is worn. Every child may joy to hear." "And the mom ("Introduction". Songs of Innocence) "Rises from the slumberous mass." ("Introduction''. Songs of Experience! 19 Chapter- 2 WILLIAM BLAKE "And I made a rural pen, And I stain'd the water clear, And I wrote my happy songs Every child may joy to hear. "1 "Then come home, my children, the sun is gone down, And the dews of night arise; Your spring and your day are wasted in play, · And your winter and night in disguise. "1 Recent researches have shown the special importance and significance of childhood in romantic poetry. Blake, being a harbinger of romanticism, had engraved childhood as a state of unalloyed joy in his Songs of Innocence. And among the romantics, be was perhaps the first to have discovered childhood. His inspiration was of course the Bible where he had seen the image of the innocent, its joy and all pure image of little, gentle Jesus. That image ignited the very ·imagination of Blake, the painter and engraver. And with his illuntined mind, he translated that image once more in his poetry, Songs of Innocence. Among the records of an early meeting of the Blake Society on 12th August, 1912 there occurs the following passage : 20 "A pleasing incident of the occasion was the presence of a very pretty robin, which hopped about unconcernedly on the terrace in front of the house and among the members while the papers were being read.. -

The Influence of William Blake on the Poetry of Thomas Merton

109 Recovering Our Innocence: the Influence ofWilliam Blake on the Poetry of Thomas Merton SONIA PETISCO Y PAPER rs GOlNG to focus on the fruitful dialogue between MThomas Merton (1915-1968) and William Blake (1757-1827), a dialogue between two interesting modern poets and thinkers who did not meet in time but in whom we find a connection of sensibilities, concepts, ways of expression and feelings. Both authors built one of the most solid paths of Modernity and tried to give a new shape to experience based on an emergent solidarity which will only flourish if we leave our individualism behind and develop our awareness of the cosmic unity, of the fact that we are ONE in the Spirit of God. Religious transfiguration of reality The poetry of Blake and Merton cannot be separated from their mystical experience. 1 In both authors, poetry is identified with religion, understanding by religion the experience of the transcend ency. They consider the poet as the intermediary between the individual soul and that soul which Renaissance man called the soul of the world or anima mundi. Through their aesthetic look, they wanted to go beyond the surface, beyond "the epidermis" in order to experience the sacredness of nature. A good example of this religious transfiguration of reality can be found in Blake's book America, a Prophecy, where he wrote this beautiful and meaningful line which immediately reminds us of the sacred character of the whole Creation. It says: "For everything that lives is holy, life delights in life." ·2 Merton also thought that everything we see in reality is an allegory of the immensity and love of God as we can realize in his poem "Stranger": When no one listens To the quiet trees THOMAS MERTON, POET-SON IA PETJSCO I I J MERTON SOCIETY-OAKHAM PAPERS , 1998 I I 0 Both Blake and Merton had read St. -

Blake's Poetry and Designs

A NORTON CRITICAL EDITION BLAKE'S POETRY AND DESIGNS ILLUMINATED WORKS OTHER WRITINGS CRITICISM Second. Edition Selected and Edited by MARY LYNN JOHNSON UNIVERSITY OF IOWA JOHN E. GRANT UNIVERSITY OF IOWA W • W • NORTON & COMPANY • New York • London Contents Preface to the Second Edition xi Introduction xiii Abbreviations xvii Note on Illustrations xix Color xix Black and White XX Key Terms XXV Illuminated Works 1 ALL RELIGIONS ARE ONE/THERE IS NO NATURAL RELIGION (1788) 3 All Religions Are One 5 There Is No Natural Religion 6 SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE (1789—94) 8 Songs of Innocence (1789) 11 Introduction 11 The Shepherd 13 The Ecchoing Green 13 The Lamb 15 The Little Black Boy 16 The Blossom 17 The Chimney Sweeper 18 The Little Boy Lost 18 The Little Boy Found 19 Laughing Song 19 A Cradle Song 20 The Divine Image 21 Holy Thursday 22 Night 23 Spring 24 Nurse's Song 25 Infant Joy 25 A Dream 26 On Anothers Sorrow 26 Songs of Experience (1793) 28 Introduction 28 Earth's Answer 30 The Clod & the Pebble 31 Holy Thursday 31 The Little Girl Lost 32 The Little Girl Found 33 vi CONTENTS The Chimney Sweeper 35 Nurses Song 36 The Sick Rose 36 The Fly 37 The Angel 38 The Tyger 38 My Pretty Rose Tree 39 Ah! Sun-Flower 39 The Lilly 40 The Garden of Love 40 The Little Vagabond 40 London 41 The Human Abstract 42 Infant Sorrow 43 A Poison Tree 43 A Little Boy Lost 44 A Little Girl Lost 44 To Tirzah 45 The School Boy 46 The Voice of the Ancient Bard 47 THE BOOK OF THEL (1789) 48 VISIONS OF THE DAUGHTERS OF ALBION (1793) 55 THE MARRIAGE OF HEAVEN AND HELL (1790) 66 AMERICA A PROPHECY (1793) 83 EUROPE A PROPHECY(1794) 96 THE SONG OF Los (1795) 107 Africa 108 Asia 110 THE BOOK OF URIZEN (1794) 112 THE BOOK OF AHANIA (1794) 130 THE BOOK OF LOS (1795) 138 MILTON: A POEM (1804; c. -

William Blake's Visions for the Eighteenth Century and Beyond

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons All NMU Master's Theses Student Works 2012 WILLIAM BLAKE’S VISIONS FOR THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY AND BEYOND Lauren Vander Lind Northern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Vander Lind, Lauren, "WILLIAM BLAKE’S VISIONS FOR THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY AND BEYOND" (2012). All NMU Master's Theses. 520. https://commons.nmu.edu/theses/520 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All NMU Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. WILLIAM BLAKE’S VISIONS FOR THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY AND BEYOND By Lauren Vander Lind THESIS Submitted to Northern Michigan University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Masters of Arts Graduate Studies Office 2012 SIGNATURE APPROVAL FORM This thesis by Lauren Vander Lind is recommended for approval by the student’s Thesis Committee and Department Head in the Department of English and by the Associate Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies. ____________________________________________________________ Committee Chair: Dr. Russell Prather Date ____________________________________________________________ Reader: Dr. Gabriel Brahm Date ____________________________________________________________ Department Head: Dr. Raymond Ventre Date ____________________________________________________________ Assistant Provost for Graduate Education and Research: Date Dr. Brian Cherry OLSON LIBRARY NORTHERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY THESIS DATA FORM In order to catalog your thesis properly and enter a record in the OCLC international bibliographic data base, Olson Library must have the following requested information to distinguish you from others with the same or similar names and to provide appropriate subject access for other researchers. -

Deoember, 1975 Shasberger, Linda M., Serpent Imagery in William

3ol7 SERPENT IMAGERY IN WILLIM BLAKE S PROPHETIC WORKS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Countil of the North Texas State University in cPartial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Linda jYi. Shasberger, B.S. in Ed. Denton, Texas Deoember, 1975 Shasberger, Linda M., Serpent Imagery in William Blake's Prophetic Works. Master of Arts (English), December, 1975, 65 pp., bibliography, 11 titles. William Blake's prophetic works are made up almost entirely of a unique combination of symbols and imagery. To understand his books it is necessary to be aware that he used his prophetic symbols because he found them apt to what he was saying, and that he changed their meanings as the reasons for their aptness changed. An awareness of this manipulation of symbols will lead to a more percep- tive understanding of Blake's work. This paper is concerned with three specific uses of serpent imagery by Blake. The first chapter deals with the serpent of selfhood. Blake uses the wingless Uraeon to depict man destroying himself through his own constrictive analytic reasonings unenlightened with divine vision. Man had once possessed this divine vision, but as formal religions and a priestly class began to be formed, he lost it and worshipped only reason and cruelty. Blake also uses the image of the ser- pent crown to characterize priests or anyone in a position of authority. He usually mocks both religious and temporal rulers and identifies them as oppressors rather than leaders of the people. In addition to the Uraeon and the serpent crown, Blake also uses the narrow constricted body of the -2- serpent and the encircled serpent to represent narrow- mindedness and selfish possessiveness. -

ABOUT the POET and HIS POETRY William Blake

ABOUT THE POET AND HIS POETRY William Blake William Blake was born in London on November 28, 1757, to James, a hosier, and Catherine Blake. Two of his six siblings died in infancy. From early childhood, Blake spoke of having visions—at four he saw God ―put his head to the window‖; around age nine, while walking dathrough the countryside, he saw a tree filled with angels. Although his parents tried to discourage him from ―lying," they did observe that he was different from his peers and did not force him to attend conventional school. He learned to read and write at home. At age ten, Blake expressed a wish to become a painter, so his parents sent him to drawing school. Two years later, Blake began writing poetry. When he turned fourteen, he apprenticed with an engraver because art school proved too costly. One of Blake‘s assignments as apprentice was to sketch the tombs at Westminster Abbey, exposing him to a variety of Gothic styles from which he would draw inspiration throughout his career. After his seven-year term ended, he studied briefly at the Royal Academy. In 1782, he married an illiterate woman named Catherine Boucher. Blake taught her to read and to write, and also instructed her in draftsmanship. Later, she helped him print the illuminated poetry for which he is remembered today; the couple had no children. In 1784 he set up a printshop with a friend and former fellow apprentice, James Parker, but this venture failed after several years. For the remainder of his life, Blake made a meager living as an engraver and illustrator for books and magazines. -

“Hold Infinity in the Palm of Your Hand and Eternity in an Hour”: William Blake’S Visions of Time and Space in the Light of Eastern Traditions

“Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand And Eternity in an hour”: William Blake’s Visions of Time and Space in the Light of Eastern Traditions by Maja Pašović A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in English - Literary Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Maja Pašović 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, in- cluding any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Abstract This thesis examines William Blake’s conceptions of time and space in the light of thephiloso- phies of Hinduism and Islam. In order to perform this analysis, source material, often from rare and neglected texts, is utilized to examine Blake’s possible unorthodox influences. The analysis of influences takes a three-pronged track: literary, symbolic, and linguistic; Blake’s possible knowledge of Orientalist translations; the symbols in his poetry, prose, and paint- ings are analyzed; and his potential knowledge of major Orientalist languages is also examined. Once this has been examined in sufficient depth, an excavation of Blake’s views on time and space is then undertaken. This analysis of Blake’s philosophical perspectives utilizes a compar- ative phenomenological approach in order to show their similarity to the perspectives of the Hindu Vedanta and Ismaili Islam. Throughout this analysis, I aim to demonstrate boththat Blake’s views on space are inherently mystical (space as limitless and unbound by the phys- ical universe), and that his view on time, having a similarity to that of the Platonists, views Eternity as the one true reality.