The Nature of Lyα Emitting Galaxies in the Reionization Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photometric Redshift Estimation of Distant Quasars

Photometric Redshift Estimation of Distant Quasars Joris van Vugt1 Department of Articial Intelligence Radboud University Nijmegen Supervisor: Dr. F. Gieseke2 Internal Supervisor: Dr. L.G. Vuurpijl3 July 6, 2016 Bachelor Thesis 1Student number: s4279859, correspondence: [email protected] 2Institute for Computing and Information Sciences, Radboud University Nijmegen 3Department of Articial Intelligence, Radboud University Nijmegen Abstract Light emitted by celestial objects is shifted towards higher wavelengths when it reaches Earth. This is called redshift. Photometric redshift estimation is necessary to process the large amount of data produced by contemporary and future telescopes. However, the lter bands recorded by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey are not sucient for accurate estimation of the redshift of high- redshift quasars. Filter bands that cover higher wavelengths, such as those in the WISE and UKIDSS catalogues provide more information. Taking these lter bands into account causes the problem of missing data, since they might not be available for every object. This thesis explores three ways of dealing with missing data: (1) discarding all objects with missing data, (2) training multiple models and (3) naively imputing the missing data. Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Astroinformatics . .3 1.2 Photometric Redshift Estimation . .3 1.2.1 Classication Versus Regression . .4 1.2.2 Algorithms Used for the SDSS Catalogue . .5 1.3 Machine Learning . .5 1.4 Datasets . .5 1.4.1 SDSS . .5 1.4.2 Quasars from SDSS, WISE and UKIDSS . .6 2 Methods 8 2.1 Supervised learning . .8 2.1.1 k-Nearest Neighbours . .8 2.1.2 Random Forests . .9 2.2 Evaluation metrics . -

Introduction to Astronomy from Darkness to Blazing Glory

Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory Published by JAS Educational Publications Copyright Pending 2010 JAS Educational Publications All rights reserved. Including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Second Edition Author: Jeffrey Wright Scott Photographs and Diagrams: Credit NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USGS, NOAA, Aames Research Center JAS Educational Publications 2601 Oakdale Road, H2 P.O. Box 197 Modesto California 95355 1-888-586-6252 Website: http://.Introastro.com Printing by Minuteman Press, Berkley, California ISBN 978-0-9827200-0-4 1 Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory The moon Titan is in the forefront with the moon Tethys behind it. These are two of many of Saturn’s moons Credit: Cassini Imaging Team, ISS, JPL, ESA, NASA 2 Introduction to Astronomy Contents in Brief Chapter 1: Astronomy Basics: Pages 1 – 6 Workbook Pages 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Time: Pages 7 - 10 Workbook Pages 3 - 4 Chapter 3: Solar System Overview: Pages 11 - 14 Workbook Pages 5 - 8 Chapter 4: Our Sun: Pages 15 - 20 Workbook Pages 9 - 16 Chapter 5: The Terrestrial Planets: Page 21 - 39 Workbook Pages 17 - 36 Mercury: Pages 22 - 23 Venus: Pages 24 - 25 Earth: Pages 25 - 34 Mars: Pages 34 - 39 Chapter 6: Outer, Dwarf and Exoplanets Pages: 41-54 Workbook Pages 37 - 48 Jupiter: Pages 41 - 42 Saturn: Pages 42 - 44 Uranus: Pages 44 - 45 Neptune: Pages 45 - 46 Dwarf Planets, Plutoids and Exoplanets: Pages 47 -54 3 Chapter 7: The Moons: Pages: 55 - 66 Workbook Pages 49 - 56 Chapter 8: Rocks and Ice: -

A Spectroscopic Redshift Measurement for a Luminous Lyman Break Galaxy at Z = 7.730 Using Keck/Mosfire

Draft version May 5, 2015 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 5/2/11 A SPECTROSCOPIC REDSHIFT MEASUREMENT FOR A LUMINOUS LYMAN BREAK GALAXY AT Z = 7:730 USING KECK/MOSFIRE P. A. Oesch1,2, P. G. van Dokkum2, G. D. Illingworth3, R. J. Bouwens4, I. Momcheva2, B. Holden3, G. W. Roberts-Borsani4,5, R. Smit6, M. Franx4, I. Labbe´4, V. Gonzalez´ 7, D. Magee3 Draft version May 5, 2015 ABSTRACT We present a spectroscopic redshift measurement of a very bright Lyman break galaxy at z = 7:7302 ± 0:0006 using Keck/MOSFIRE. The source was pre-selected photometrically in the EGS field as a robust z ∼ 8 candidate with H = 25:0 mag based on optical non-detections and a very red Spitzer/IRAC [3.6]−[4.5] broad-band color driven by high equivalent width [O III]+Hβ line emission. The Lyα line is reliably detected at 6:1σ and shows an asymmetric profile as expected for a galaxy embedded in a relatively neutral inter-galactic medium near the Planck peak of cosmic reionization. ˚ +90 The line has a rest-frame equivalent width of EW0 = 21 ± 4 A and is extended with VFWHM = 360−70 km s−1. The source is perhaps the brightest and most massive z ∼ 8 Lyman break galaxy in the 9:9±0:2 full CANDELS and BoRG/HIPPIES surveys, having assembled already 10 M of stars at only 650 Myr after the Big Bang. The spectroscopic redshift measurement sets a new redshift record for galaxies. This enables reliable constraints on the stellar mass, star-formation rate, formation epoch, as well as combined [O III]+Hβ line equivalent widths. -

Rev 06/2018 ASTRONOMY EXAM CONTENT OUTLINE the Following

ASTRONOMY EXAM INFORMATION CREDIT RECOMMENDATIONS This exam was developed to enable schools to award The American Council on Education’s College credit to students for knowledge equivalent to that learned Credit Recommendation Service (ACE CREDIT) by students taking the course. This examination includes has evaluated the DSST test development history of the Science of Astronomy, Astrophysics, process and content of this exam. It has made the Celestial Systems, the Science of Light, Planetary following recommendations: Systems, Nature and Evolution of the Sun and Stars, Galaxies and the Universe. Area or Course Equivalent: Astronomy Level: 3 Lower Level Baccalaureate The exam contains 100 questions to be answered in 2 Amount of Credit: 3 Semester Hours hours. Some of these are pretest questions that will not Minimum Score: 400 be scored. Source: www.acenet.edu Form Codes: SQ500, SR500 EXAM CONTENT OUTLINE The following is an outline of the content areas covered in the examination. The approximate percentage of the examination devoted to each content area is also noted. I. Introduction to the Science of Astronomy – 5% a. Nature and methods of science b. Applications of scientific thinking c. History of early astronomy II. Astrophysics - 15% a. Kepler’s laws and orbits b. Newtonian physics and gravity c. Relativity III. Celestial Systems – 10% a. Celestial motions b. Earth and the Moon c. Seasons, calendar and time keeping IV. The Science of Light – 15% a. The electromagnetic spectrum b. Telescopes and the measurement of light c. Spectroscopy d. Blackbody radiation V. Planetary Systems: Our Solar System and Others– 20% a. Contents of our solar system b. -

The Large Scale Universe As a Quasi Quantum White Hole

International Astronomy and Astrophysics Research Journal 3(1): 22-42, 2021; Article no.IAARJ.66092 The Large Scale Universe as a Quasi Quantum White Hole U. V. S. Seshavatharam1*, Eugene Terry Tatum2 and S. Lakshminarayana3 1Honorary Faculty, I-SERVE, Survey no-42, Hitech city, Hyderabad-84,Telangana, India. 2760 Campbell Ln. Ste 106 #161, Bowling Green, KY, USA. 3Department of Nuclear Physics, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam-03, AP, India. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Author UVSS designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors ETT and SL managed the analyses of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information Editor(s): (1) Dr. David Garrison, University of Houston-Clear Lake, USA. (2) Professor. Hadia Hassan Selim, National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics, Egypt. Reviewers: (1) Abhishek Kumar Singh, Magadh University, India. (2) Mohsen Lutephy, Azad Islamic university (IAU), Iran. (3) Sie Long Kek, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, Malaysia. (4) N.V.Krishna Prasad, GITAM University, India. (5) Maryam Roushan, University of Mazandaran, Iran. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/66092 Received 17 January 2021 Original Research Article Accepted 23 March 2021 Published 01 April 2021 ABSTRACT We emphasize the point that, standard model of cosmology is basically a model of classical general relativity and it seems inevitable to have a revision with reference to quantum model of cosmology. Utmost important point to be noted is that, ‘Spin’ is a basic property of quantum mechanics and ‘rotation’ is a very common experience. -

Elements of Astronomy and Cosmology Outline 1

ELEMENTS OF ASTRONOMY AND COSMOLOGY OUTLINE 1. The Solar System The Four Inner Planets The Asteroid Belt The Giant Planets The Kuiper Belt 2. The Milky Way Galaxy Neighborhood of the Solar System Exoplanets Star Terminology 3. The Early Universe Twentieth Century Progress Recent Progress 4. Observation Telescopes Ground-Based Telescopes Space-Based Telescopes Exploration of Space 1 – The Solar System The Solar System - 4.6 billion years old - Planet formation lasted 100s millions years - Four rocky planets (Mercury Venus, Earth and Mars) - Four gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune) Figure 2-2: Schematics of the Solar System The Solar System - Asteroid belt (meteorites) - Kuiper belt (comets) Figure 2-3: Circular orbits of the planets in the solar system The Sun - Contains mostly hydrogen and helium plasma - Sustained nuclear fusion - Temperatures ~ 15 million K - Elements up to Fe form - Is some 5 billion years old - Will last another 5 billion years Figure 2-4: Photo of the sun showing highly textured plasma, dark sunspots, bright active regions, coronal mass ejections at the surface and the sun’s atmosphere. The Sun - Dynamo effect - Magnetic storms - 11-year cycle - Solar wind (energetic protons) Figure 2-5: Close up of dark spots on the sun surface Probe Sent to Observe the Sun - Distance Sun-Earth = 1 AU - 1 AU = 150 million km - Light from the Sun takes 8 minutes to reach Earth - The solar wind takes 4 days to reach Earth Figure 5-11: Space probe used to monitor the sun Venus - Brightest planet at night - 0.7 AU from the -

12 Strong Gravitational Lenses

12 Strong Gravitational Lenses Phil Marshall, MaruˇsaBradaˇc,George Chartas, Gregory Dobler, Ard´ısEl´ıasd´ottir,´ Emilio Falco, Chris Fassnacht, James Jee, Charles Keeton, Masamune Oguri, Anthony Tyson LSST will contain more strong gravitational lensing events than any other survey preceding it, and will monitor them all at a cadence of a few days to a few weeks. Concurrent space-based optical or perhaps ground-based surveys may provide higher resolution imaging: the biggest advances in strong lensing science made with LSST will be in those areas that benefit most from the large volume and the high accuracy, multi-filter time series. In this chapter we propose an array of science projects that fit this bill. We first provide a brief introduction to the basic physics of gravitational lensing, focusing on the formation of multiple images: the strong lensing regime. Further description of lensing phenomena will be provided as they arise throughout the chapter. We then make some predictions for the properties of samples of lenses of various kinds we can expect to discover with LSST: their numbers and distributions in redshift, image separation, and so on. This is important, since the principal step forward provided by LSST will be one of lens sample size, and the extent to which new lensing science projects will be enabled depends very much on the samples generated. From § 12.3 onwards we introduce the proposed LSST science projects. This is by no means an exhaustive list, but should serve as a good starting point for investigators looking to exploit the strong lensing phenomenon with LSST. -

The Milky Way Almost Every Star We Can See in the Night Sky Belongs to Our Galaxy, the Milky Way

The Milky Way Almost every star we can see in the night sky belongs to our galaxy, the Milky Way. The Galaxy acquired this unusual name from the Romans who referred to the hazy band that stretches across the sky as the via lactia, or “milky road”. This name has stuck across many languages, such as French (voie lactee) and spanish (via lactea). Note that we use a capital G for Galaxy if we are talking about the Milky Way The Structure of the Milky Way The Milky Way appears as a light fuzzy band across the night sky, but we also see individual stars scattered in all directions. This gives us a clue to the shape of the galaxy. The Milky Way is a typical spiral or disk galaxy. It consists of a flattened disk, a central bulge and a diffuse halo. The disk consists of spiral arms in which most of the stars are located. Our sun is located in one of the spiral arms approximately two-thirds from the centre of the galaxy (8kpc). There are also globular clusters distributed around the Galaxy. In addition to the stars, the spiral arms contain dust, so that certain directions that we looked are blocked due to high interstellar extinction. This dust means we can only see about 1kpc in the visible. Components in the Milky Way The disk: contains most of the stars (in open clusters and associations) and is formed into spiral arms. The stars in the disk are mostly young. Whilst the majority of these stars are a few solar masses, the hot, young O and B type stars contribute most of the light. -

Mapping Weak Gravitational Lensing Signals from Low-Redshift Galaxy Clusters to Compare Dark Matter and X-Ray Gas Substructures

MAPPING WEAK GRAVITATIONAL LENSING SIGNALS FROM LOW-REDSHIFT GALAXY CLUSTERS TO COMPARE DARK MATTER AND X-RAY GAS SUBSTRUCTURES. CLAIRE HAWKINS BROWN UNIVERSITY MAY 2020 1 Contents Acknowledgements: ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract: ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction: .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Background: .................................................................................................................................................. 7 GR and Gravitational Lensing .................................................................................................................. 7 General Relativity ................................................................................................................................. 7 Gravitational Lensing ............................................................................................................................ 9 Galaxy Clusters ....................................................................................................................................... 11 Introduction to Galaxy Clusters ......................................................................................................... -

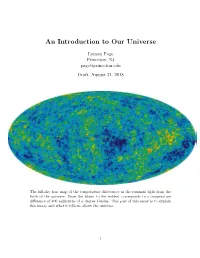

An Introduction to Our Universe

An Introduction to Our Universe Lyman Page Princeton, NJ [email protected] Draft, August 31, 2018 The full-sky heat map of the temperature differences in the remnant light from the birth of the universe. From the bluest to the reddest corresponds to a temperature difference of 400 millionths of a degree Celsius. The goal of this essay is to explain this image and what it tells us about the universe. 1 Contents 1 Preface 2 2 Introduction to Cosmology 3 3 How Big is the Universe? 4 4 The Universe is Expanding 10 5 The Age of the Universe is Finite 15 6 The Observable Universe 17 7 The Universe is Infinite ?! 17 8 Telescopes are Like Time Machines 18 9 The CMB 20 10 Dark Matter 23 11 The Accelerating Universe 25 12 Structure Formation and the Cosmic Timeline 26 13 The CMB Anisotropy 29 14 How Do We Measure the CMB? 36 15 The Geometry of the Universe 40 16 Quantum Mechanics and the Seeds of Cosmic Structure Formation. 43 17 Pulling it all Together with the Standard Model of Cosmology 45 18 Frontiers 48 19 Endnote 49 A Appendix A: The Electromagnetic Spectrum 51 B Appendix B: Expanding Space 52 C Appendix C: Significant Events in the Cosmic Timeline 53 D Appendix D: Size and Age of the Observable Universe 54 1 1 Preface These pages are a brief introduction to modern cosmology. They were written for family and friends who at various times have asked what I work on. The goal is to convey a geometrical picture of how to think about the universe on the grandest scales. -

Milky Way Haze

CURIOSITY AT HOME MILKY WAY HAZE A galaxy is a group of stars, gas and dust. Our solar system is part of the Milky Way Galaxy. This galaxy appears as a milky haze in the night sky. Have you ever wondered why the Milky Way resembles a hazy, cloud-like strip in the sky? MATERIALS • Paper hole punch • Glue • Black construction paper • White paper • Masking or painter’s tape • Pen • Paper or science notebook PROCEDURE • Use the hole punch to cut out 50 circles from the white paper. • Glue the circles very close together in the center of the black sheet of paper. • Tape the black construction paper to a pole, tree, wall or other outside object you will be able to see from a distance. • Stand so your nose is almost touching the black construction paper. • Draw or write about your observations on a piece of paper or in your science notebook. • Slowly back away until the separate circles can no longer be seen. • Estimate or measure how far away you were when you could no longer see the separate circles. • What do you notice about the circles seen from a distance as compared to close up? DID YOU KNOW Our eyes are unable to distinguish small points of light that are very close together. Rather, the separate points of light blend together. In our galaxy, the light from distant stars blends together to form the Milky Way haze. The Milky Way galaxy is home to all of the stars that are visible to the naked eye as well as billions of stars that are so far away our eyes are unable to distinguish each individual point of star light. -

Observational Searches for Star-Forming Galaxies at Z > 6

Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia (PASA), Vol. 33, e037, 35 pages (2016). C Astronomical Society of Australia 2016; published by Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/pasa.2016.26 Observational Searches for Star-Forming Galaxies at z > 6 Steven L. Finkelstein1,2 1Department of Astronomy, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 2Email: [email protected] (Received November 19, 2015; Accepted June 23, 2016) Abstract Although the universe at redshifts greater than six represents only the first one billion years (<10%) of cosmic time, the dense nature of the early universe led to vigorous galaxy formation and evolution activity which we are only now starting to piece together. Technological improvements have, over only the past decade, allowed large samples of galaxies at such high redshifts to be collected, providing a glimpse into the epoch of formation of the first stars and galaxies. A wide variety of observational techniques have led to the discovery of thousands of galaxy candidates at z > 6, with spectroscopically confirmed galaxies out to nearly z = 9. Using these large samples, we have begun to gain a physical insight into the processes inherent in galaxy evolution at early times. In this review, I will discuss (i) the selection techniques for finding distant galaxies, including a summary of previous and ongoing ground and space-based searches, and spectroscopic follow-up efforts, (ii) insights into galaxy evolution gleaned from measures such as the rest-frame ultraviolet luminosity function, the stellar mass function, and galaxy star-formation rates, and (iii) the effect of galaxies on their surrounding environment, including the chemical enrichment of the universe, and the reionisation of the intergalactic medium.