Draft Environmental Impact Statement Bog Creek Road Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download The

Visitors • Newcomers • Locals THE source for everything North Idaho... Lake Coeur d’Alene | Bookmark Lake Pend it Oreilletoday! | Beaches & Docks | Trails | Driving Tours | Shopping | Unique Experiences to North Idaho See Ya! Looking to prepare for a career or develop professionally? Visit us at 1 location in Coeur d’Alene Explore your options at NorthIdahoHigherEducation.org/take-action MAKE AN APPOINTMENT TODAY www.nic.edu www.lcsc.edu/cda www.uidaho.edu/cda sspa.boisestate.edu/ www.isu.edu 208.769.3456 208.666.6707 208.667.2588 socialwork 208.282.7818 208.426.1568 Welcome! Coeur d'Alene • Sandpoint • Post Falls Hayden Lake • Twin Lakes • Spirit Lake • Rathdrum • Bayview Kellogg • Hayden • Hope • Wallace • Harrison • St. Maries Priest Lake • Priest River • Bonners Ferry • Worley-Plummer and Surrounding Communities North Idaho and the Inland Northwest are the aboriginal 1 CABELA’S homelands to a number of Indian tribes. The names of 6 2 COEUR D'ALENE CASINO many cities and landmarks are derived from these tribal Looking to prepare for a career or develop professionally? 3 FARRAGUT STATE PARK languages. While not all local names are tribal, visitors 4 GREYHOUND PARK and newcomers can refer to this list of challenging-to- pronounce names to sound like you’ve been here for years! 5 HEYBURN STATE PARK 9 6 KOOTENAI WILDLIFE REFUGE Coeur d’Alene - core da LANE Q’emiln - ka MEE lin Kootenai - KOOT in ee Shoshone - sho SHONE Visit us at 1 location in Coeur d’Alene 7 LOOKOUT SKI AREA Moscow - MOSS co Seltice - sell TEECE DISCOVER 8 OLD MISSION STATE PARK Moyie - moy A St. -

Click for a PDF

T B.C. ISI HA V L The F International Border Crossing is Currently V CLOSED IS IT F U.S. HAL VISIT NORTH AMERICA’S ON LY MULTI-COUNTRY SCENIC LOOP Visit Idaho, Washington 1.888.823.2626 and Montana www.selkirkloop.org Go wild In the wild. Getting out and exploring the beautiful Pend Oreille Valley is an unforgettable experience. And so is playing the latest slots, enjoying some Northwest comfort food and relaxing in a neighborly lounge! Do it all at Kalispel Casino where you can dine in Wetlands restaurant, have a cold one at The Slough, and play your favorite games. You can even stay for days at the adjoining RV resort featuring hookups, tent sites and cottages. Or just fill up on freshf food, fountain drinks and Chevron fuel at Kalispel Market. Where serenity meets Amenities. on the 420 Qlispe River Way, Cusick, WA Kalispel2 Tribe Reservation www.selkirkloop.org Pend Oreille River at the foot of the Selkirks 1-833-881-7492 | kalispelcasino.com U.S. DESTINATIONS Athol, Idaho ..................................................... 24 Bayview, Idaho ................................................ 24 Blanchard, Idaho ............................................ 24 The international border is currently closed to non- Bonners Ferry, Idaho ..................................... 36 essential travel at this time. However, Canadian Chewelah, Washington ................................. 10 residents can visit the BC half of the Loop. Clark Fork, Idaho ............................................ 33 Colville, Washington ...................................... 10 riving the International Selkirk Loop is Cusick, Washington ....................................... 14 Dtruly a spectacular experience, as the 280- Hope, Idaho..................................................... 33 mile (450 km) international scenic byway winds Ione, Washington ..............................................8 around the Selkirk Mountains through Idaho and Metaline/Metaline Falls, Washington............6 Washington, USA, and British Columbia, Canada. -

The Priest River Bioregional Atlas

[Type text] The Priest River Bioregional Atlas Authors Morgan Bessaw Nick Brown Jesse Buster Danielle Clelland Rebecca Couch Genny Gerke Melissa Hamilton Matthew Jensen Liz Lind Lisa Marshall Liza Pulsipher Monica Walker Project Advisor Dr. Tamara J. Laninga Editor Sue Traver Acknowledgements Special thanks go to the residents of Priest River and the surrounding environs; Sue Traver, University of Idaho Extension faculty; City of Priest River Mayor Jim Martin and the City Council; the Priest River Community Advisory Board, chaired by Wayne Benner; and all of the people interviewed for this atlas including: Bob Denner, Joe Summers, Jack Johnson, Jonny Wilson, Clare Marley, Dan Carlson, Susan Cabear, Dick Cramer, Karl Dye, Marilyn Cork, Marie Duncan, Mike McGuire, Ken Reed, Kerri Martin, Les Kokanos, Mike Bauer, and Danny Barney. We also thank Ted and Rita Runberg for all their support and a great BB and Katie Crill and the Priest River Library Branch for all their assistance and the use of their conference room. Finally, we thank the University of Idaho’s Building Sustainable Communities Initiative for supporting the Bioregional Planning and Community Design program. December 2009 [Type text] Preface [Type text] Table of Contents1 Introduction Section1: Biophysical Section 2: Protected Areas Section 3: Cultural Landscapes Section 4: History Section 5: Agriculture Section 6: Political and Nongovernmental Institutions Section 7: Land Use Section 8: Infrastructure Section 9: Transportation Section 10: Demographics Section 11: Economics Section 12: Housing Section 13: Education Section14: Health and Safety Section 15: Community Life Conclusion 1 The information provided in this atlas is subject to change – please verify all information prior to any decision making processes based on the contents of any section in the atlas. -

Fsm8 036264.Pdf

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Biological Opinion and Conference Opinion for the Modified Idaho Roadless Rule USDA Forest Service Regions 1 and 4 14420-2008-F-0586 September 2008 - Snake River Fish and Wildlife Office - Boise, Idaho TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 12 A. Background 12 B. Previous Consultations Involving Idaho Roadless Areas 12 C. Consultation History 14 D. Purpose and Organization of this Biological Opinion 21 CHAPTER II: DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSED ACTION 24 A. Action Area 24 B. Purpose and Need of the Proposed Action 25 C. Proposed Action 25 D. Time Frames, Scope and Applicability for the Proposed Action 37 E. Administrative Corrections 38 F. Modifications 38 G. Applicability of Previous Consultations to Proposed Action 39 H. Relationship of Existing Forest Plans to Proposed Action 39 I. Assumptions Pertaining to the Proposed Action 41 CHAPTER III. BULL TROUT 46 A. Status of the Species 46 1. Listing History 46 2. Description of the Species 47 3. Life History and Habitat Requirements 47 4. Population Dynamics 48 5. Distribution 50 6. Previously Consulted-on Effects 53 7. Conservation Needs 54 8. Critical Habitat 54 B. Environmental Baseline: 55 1. Status of the Species in the Action Area 55 2. Factors Affecting the Species in the Action Area 56 C. Effects of the Proposed Action 59 D. Cumulative Effects 68 E. Conclusion 69 F. Incidental Take Statement 70 1. Amount or Extent of the Take 70 2. Effect of the Take 70 3. Reasonable and Prudent Measures and Terms and Conditions 70 G. Conservation Recommendations 70 CHAPTER IV: SELKIRK MOUNTAINS WOODLAND CARIBOU 72 A. -

Climate of Priest River Experimental Forest, Northern Idaho

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. United States Department of Agriculture Climate of Forest Service Intermountain Forest and Range Priest River Experiment Station Ogden, UT 84401 General Technical Experimental Forest, Report INT-159 December 1983 Northern Idaho Arnold I. Finklin THE AUTHOR CONTENTS Page ARNOLD I. FINKLIN is a meteorologist at the Northern Introduction .................................................................. 1 Forest Fire Laboratory, Missoula, Mont. Specializing in Description of the Area................................................. 1 climatology, he is currently with the Fire Effects and Stations; Data; Methods ............................................... 3 Use Research and Development Program. Previous Fire-Weather Data .................................................... 4 assignments at this location were with Project Skyfire Averages; “Normals”................................................. 4 and the Fire in Multiple Use Research, Development, Condensed Climatic Summary..................................... 5 and Application Program. He received a master’s Details of the Climate ................................................... 6 degree in atmospheric science from Colorado State Precipitation .............................................................. 6 University before joining the laboratory in 1967. Annua| Precipitation .............................................. 6 Monthly Distribution -

History of Priest River

History of the Priest United States River Experiment Station Department of Agriculture Forest Service Kathleen L. Graham Rocky Mountain Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-129 June 2004 Graham, Kathleen L. 2004. History of the Priest River Experiment Station. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS- GTR-129. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 71 p. Abstract In 1911, the U.S. Forest Service established the Priest River Experimental Forest near Priest River, Idaho. The Forest served as headquarters for the Priest River Forest Experiment Station and continues to be used for forest research critical to understanding forest development and the many processes, structures, and functions occurring in them. At the time the Forest was created, Idaho had been a State for only 11 years. The early Forest Service leaders, such as Gifford Pinchot, Raphael Zon, and Henry Graves, were creating a new department and making decisions that would impact the culture, economics, and history of not only the State of Idaho and the Northwest, but the nation. The location of the Forest, in a remote section of northern Idaho, was due partly to the need for research on tree species within the Pacific Coast forest region, but also because it contained large amounts of western white pine, the prized tree species for construction. Since the Forest’s establishment, numerous Forest Service researchers, educators from colleges and universities across the nation, and State and private forestry personnel have used the Forest to solve problems impacting forests and economics, not only locally and regionally but also worldwide. -

2018Calendar

2018 CALENDAR CONNECTING PEOPLE WHO CARE WITH CAUSES THAT MATTER Inland Northwest Community Foundation Who we are… fosters vibrant and sustainable communities As the community foundation for the Inland Northwest, we help people who care in the Inland Northwest. about our region accomplish their charitable goals. Community foundation staff and volunteers work with individuals, families, businesses and nonprofit organizations W Boundary ASHINGTON Pend to establish charitable funds. We professionally manage and invest those funds, Oreille Ferry Stevens which yield revenue to support a wide variety of grants that foster vibrant and Bonner sustainable communities. Since its inception in 1974, more than $65 million has been distributed for charitable purposes. Kootenai Lincoln Spokane THANKS TO OUR SPONSORS Benewah Shoshone Adams Whitman Latah Clearwater Garfield Nez Perce Columbia Lewis Asotin Idaho The counties Inland Northwest Community Foundation serves. IDAHO The Feuerstein Group, Inc. Cover photo: Rose Creek Nature Preserve courtesy of Pallouse-Clearwater Environmental Institute (PCEI) pcei.org Cover photo: Rose Creek Nature Preserve courtesy of Pallouse-Clearwater Environmental Institute (PCEI) pcei.org CONNECTING PEOPLE WHO CARE AT A GLANCE WITH CAUSES THAT MATTER (AS OF 6/30/2017) Dear Friends, TOTAL GIFTS RECEIVED $12.7 MILLION Inland Northwest Community Foundation’s fiscal year 2017, ending on June INCLUDING BEQUEST GIFTS OF $4.1 MILLION 30, was remarkable in many ways. Thanks to the generosity of those who believe in the promise of a better region through community philanthropy, GIFTS we received more than $16 million in gifts and bequests. With the addition 665 of 29 new funds, we now professionally manage and invest nearly 500 437 DONORS funds that comprise total assets of $114 million. -

A Social History of Wild Huckleberry Harvesting in the Pacific Northwest

United States Department of Agriculture A Social History of Wild Forest Service Huckleberry Harvesting Pacific Northwest Research Station General Technical in the Pacific Northwest Report PNW-GTR-657 Rebecca T. Richards and Susan J. Alexander February 2006 The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the prin- ciple of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the national forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Rebecca T. Richards is a professor, Department of Sociology, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812, and Susan J. -

Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail Mapset

CANADA Chief Mountain (Port of Entry) Kishenehn Eastern UNITED STATES Waterton Lake North Boundary Trail Terminus 24 mi Boulder Pass Trail Kintla Creek 17 Ketchikan Creek 35A Trail Kintla Trail Boulder N Fork Rd Pass North Fork Belly River A GLACIER 45 7 mi Brown Pass Goat Haunt Kintla Lake Pocket Lake Kintla Peak 8 mi Brown Pass Tr (Port of Entry) NATIONAL Parke Ridge EL 10,101 PARK 26 mi Belly River Tr Lake 52 Lake Trail Creek Rd Kintla Agassiz dribrednuhT Janet Glacier Frances 1 Trail Creek Glacier Glacier Mt Cleveland Kintla Porcupine Ridge 5 GLACIER Bowman 5 EL 10,466 Lake NATIONAL Lake Trail Porcupine Lookout ylleB reviR Tepee Creek N Fork Rd PARK Waterton Stoney Indian Reuter Peak Valentine Creek Glenns Tepee Creek Rd 45C EL 8,763 Lake Ford Creek 53 NF 9805 5 Pass Trail 19 mi Rainbow Valley Trail Old Sun Whale Creek Rd Stoney Inside N Fork Rd Glacier Glacier Helen Lake Trail Indian Pass 15 mi MokawanisRiver FLATHEAD Bowman Lake Kootenai NATIONAL Cerulean Ridge Ahern Kennedy Creek Two Oceans Creek Glacier FOREST Quartz Lake Continental Creek Loop Trail Glacier Waterton River Moose Flathead River Ptarmigan Tr North Fork Akokala Creek 5 Nahsukin Lake Moose Creek Rd Vulture 12 mi Glacier Flattop Mtn Trail Quartz Lake Flattop Mountain Many Glacier NF 486 Quartz Ridge Trapper Pk EL 7,702 5 Red Meadow Creek Logging Mtn EL 8,566 55C Grace Lake Red Meadow Rd 2 mi McDonald Creek 46 mi Hay Creek 54 Cummings Creek Swicurrent Pass Tr Hay Creek Rd 5 Piegan Pass Tr NF 376 Logging Lake Trail Longfellow Creek Grinnell Red Meadow Hay Creek Tr NF -

RECEIVED 413 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NFS Foim 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10/90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service RECEIVED 413 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and distric . See instri :tions in How to Complete the National Rei of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by ma requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not ap i cable, ia|s' and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place ad ional entri ntmuation sheets Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. m historic name Priest River Commercial Core Historic District other names/site number iliiiiiiiliiiilii street & number: Roughly bounded by Wisconsin. Montgomery, and Cedar streets and Albeni Road________________ n/a not for publication city or town Priest River __________________________________ n/a vicinity_______ state Idaho code ID county Bonner code 017 zip code 83856 As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _X_nomination _request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_meets _does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant _nationally _statewide _Xlocally. (_ See continuation sheet f or/acfelj t i ona 11 ddjtAsnts., Signature Oflf^eTtffyvng official •—- -^ John R. -

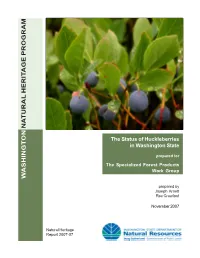

W Ashingt on Na Tural Herit Age Program

NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM HERITAGE NATURAL The Status of Huckleberries in Washington State prepared for The Specialized Forest Products Work Group WASHINGTON prepared by Joseph Arnett Rex Crawford November 2007 Natural Heritage Report 2007-07 The Status of Huckleberries in Washington State Joseph Arnett Rex Crawford Washington Natural Heritage Program November 30, 2007 Contents Executive Summary...................................................................................... 1 I. Introduction ............................................................................................... 3 II. Huckleberry Species in Washington...................................................... 5 III. Huckleberry Ecology ........................................................................... 27 IV. References ............................................................................................. 35 Tables Table 1. Huckleberry Species in Washington State Table 2. Comparative nomenclature of huckleberry species Table 3. Habitat and distribution of Washington huckleberries Table 4. Distribution of huckleberry species in forest associations in Washington Appendices Appendix 1. Huckleberries and humans Appendix 2. Potential contacts on huckleberry harvest Appendix 3. Scientific names of species included in the text Appendix 4. Notes from personal communications Executive Summary This report includes a summary of the biology and ecology of native huckleberries (the genus Vaccinium, exclusive of cranberries) in Washington State. Washington’s Specialized -

2019 PROJECT PLAN Priest River Coldwater Bypass Alternatives

Project Operations Package Appendix T As recommended by the WRTAC on 1/22/2019 for MC consideration 2019 PROJECT PLAN Priest River Coldwater Bypass Alternatives Assessment Project Contact Kiira Siitari, Idaho Department of Fish and Game, (208)769-1414, [email protected] Project History This is a continuing project, first approved for 2018. There are no changes to the budget. Reporting timelines have been updated for 2019. The first phase of the project, contracted by the Kalispel Tribe with Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) funding, and completed in 2014, resulted in a stream temperature and flow model developed by the Water Quality Research Group at Portland State University (Berger et al. 2014). This hydrodynamic model predicted that replacing a portion of the epilimnetic water released from the Priest Lake Outlet Dam with cold water from the hypolimion would result in up to a 10°C decrease in late summer stream temperatures. Temperature reductions would primarily benefit the most stenothermic native salmonids in the Priest and Pend Oreille systems, namely migratory bull trout and westslope cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkia lewisi) which inhabit Lake Pend Oreille. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game alternatives analysis is needed to better assess bypass feasibility, cost, and public interest, and ultimately inform whether or not they will further pursue this potential project. Background Lower Priest River begins at the outlet of Priest Lake in northern Idaho. The stream flows 45 miles south to its confluence with the Pend Oreille River, upstream from Albeni Falls Dam (Figure 1). Priest River is hydrologically connected to Lake Pend Oreille with no barriers to fish movement, and like a number of other Idaho tributaries to the system, provides spawning and early rearing habitat for Lake Pend Oreille bull trout.