Heidegger and Leonard Cohen: “You Want It Darker”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 JUNO Award Nominees Updated: February 7, 2017

2017 JUNO Award Nominees Updated: February 7, 2017 JUNO FAN CHOICE (PRESENTED BY TD) Alessia Cara Def Jam*Universal Belly Roc Nation*Universal Drake Cash Money*Universal Hedley Universal Justin Bieber Def Jam*Universal Ruth B Columbia*Sony Shawn Mendes Island*Universal The Strumbellas Six Shooter*Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Tory Lanez Interscope*Universal SINGLE OF THE YEAR Wild Things Alessia Cara Def Jam*Universal One Dance ft. Wizkid & Kyla Drake Cash Money*Universal Treat You Better Shawn Mendes Island*Universal Spirits The Strumbellas Six Shooter*Universal Starboy ft. Daft Punk The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal INTERNATIONAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY IDLA ASSOCIATED LABEL DISTRIBUTION) Dangerous Woman Ariana Grande Republic*Universal A Head Full of Dreams Coldplay Parlophone*Warner Made in the A.M. One Direction Sony ANTI Rihanna Westbury Road*Universal This is Acting Sia RCA*Sony ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY MUSIC CANADA) Encore un Soir Céline Dion Sony Views Drake Cash Money*Universal You Want It Darker Leonard Cohen Sony Illuminate Shawn Mendes Island*Universal Starboy The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal ARTIST OF THE YEAR Alessia Cara Def Jam*Universal Drake Cash Money*Universal Leonard Cohen Sony Shawn Mendes Island*Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal GROUP OF THE YEAR Arkells Arkells*Universal Billy Talent Warner Tegan and Sara Warner Bros. -

New Jerusalem Glowing: Songs and Poems of Leonard Cohen in A

New Jerusalem Glowing Songs and Poems of Leonard Cohen in a Kabbalistic Key Elliot R. Wolfson In Book of Mercy, published in 1984, the Montréal Jewish poet, Leonard Cohen addressed his master: Sit down, Master, on the rude chair of praises, and rule my nervous heart with your great decrees of freedom. Out of time you have taken me to do my daily task. Out of mist and dust you have fashioned me to know the numberless worlds between the crown and the kingdom. In utter defeat I came to you and you received me with a sweetness I had not dared to remember. Tonight I come to you again, soiled by strategies and trapped in the loneliness of my tiny domain. Establish your law in this walled place. Let nine men come to lift me into their prayer so that I may whisper with them: Blessed be the name of the glory of the kingdom forever and forever.1 In this prayer, the poet offers us a way to the heart of the matter that I will discuss in this study, however feebly, the songs and poems of Leonard Cohen in the key of the symbolism of kabbalah, the occult oral tradition of Judaism purported to be ancient, but historically detectable (largely through textual evidence) from the late Middle Ages. To those even somewhat familiar with 2 the background of the Canadian bard, the topic should not come as a surprise. 1 Leonard Cohen, Book of Mercy, New York 1984, p. 16. 2 The original version of this study was delivered as a lecture at McGill University, October 18, 2001. -

Nielsen Music Year-End Report Canada 2016

NIELSEN MUSIC YEAR-END REPORT CANADA 2016 NIELSEN MUSIC YEAR-END REPORT CANADA 2016 Copyright © 2017 The Nielsen Company 1 Welcome to the annual Nielsen Music Year End Report for Canada, providing the definitive 2016 figures and charts for the music industry. And what a year it was! The year had barely begun when we were already saying goodbye to musical heroes gone far too soon. David Bowie, Leonard Cohen, Glenn Frey, Leon Russell, Maurice White, Prince, George Michael ... the list goes on. And yet, despite the sadness of these losses, there is much for the industry to celebrate. Music consumption is at an all-time high. Overall consumption of album sales, song sales and audio on-demand streaming volume is up 5% over 2015, fueled by an incredible 203% increase in on-demand audio streams, enough to offset declines in sales and return a positive year for the business. 2016 also marked the highest vinyl sales total to date. It was an incredible year for Canadian artists, at home and abroad. Eight different Canadian artists had #1 albums in 2016, led by Drake whose album Views was the biggest album of the year in Canada as well as the U.S. The Tragically Hip had two albums reach the top of the chart as well, their latest release and their 2005 best of album, and their emotional farewell concert in August was something we’ll remember for a long time. Justin Bieber, Billy Talent, Céline Dion, Shawn Mendes, Leonard Cohen and The Weeknd also spent time at #1. Break out artist Alessia Cara as well as accomplished superstar Michael Buble also enjoyed successes this year. -

Boletín Novas Adquisicions Audiovisuais Setembro-Outubro

BOLETÍN DE NOVAS ADQUISICIÓNS AUDIOVISUAIS ADULTOS Biblioteca Municipal de Ferrol ssetembroetembro – outubro 2017 CINE DE ADULTOS DVDDVDDVD 1898 los últimos de Filipinas / dirigida por Salvador Calvo ; música original, Roque Baños ; guión, Alejandro Hernández Ano de realización: 2016 Duración:Duración:Duración: 124 min. Localización: CINE 791-H MIL 100 metros / escrita y dirigida por Marcel Barrena ; música, Rodrigo Leào Ano de realización: 2016 Duración:Duración:Duración: 102 min. Localización: CINE 791-DM CIE La llegada = Arrival / directed by Denis Villeneuve ; screenplay by Eric Heisserer ; music by Johann Johannsson Ano de realización: 2016 Duración:Duración:Duración: 112 min. Localización: CINE 791-FT LLE Toni Erdmann / escrita y dirigida por Maren Ade AnoAno de realización: 2016 Duración:Duración:Duración: 156 min. Localización: CINE 791-C TON La tortuga roja / director, Michael Dudok de Wit ; guión, Michael Dudok de Wit, Pascale Ferran ; música, Laurent Perez del Mar Ano de realización: 2016 Duración:Duración:Duración: 77 min. Localización: CINE 791-DA TOR La muerte cansada : (las tres luces) = A morte cansada = Der müde tod / guión y dirección, Fritz Lang ; música compuesta por Cornelius Schwehr Ano de realización: 1921 Duración:Duración:Duración: 98 min. Localización: CINE 791-FT MUE Ladrón de bicicletas / director, Vittorio de Sica ; argumento y guión, Cesare Zavattini ... et al. ; música, Alessandro Cicognini Ano de realización: 1948 Duración:Duración:Duración: 86 min. Localización: CINE 791-DM LAD O segredo da Frouxeira = (El secreto de A Frouxeira) / [guión e dirección, Xosé Abad ; música, Marcelino Abad; voz solista, Estíbaliz Espinosa] Ano de realización: 2009 Duración:Duración:Duración: 60 min. Localización: CINE 791-D SEG La balada de Narayama = Narayama bushiko / [director, Shohei Imamura ; guión, Shohei Imamura ; música, Shinichiro Ikebe] Ano de realización: 1983 Duración:Duración:Duración: 133 min. -

Bios the Cast Timothy Leary Ram Dass Dr. Andrew Weil

BIOS THE CAST TIMOTHY LEARY In the early 1960s Harvard psychology professors Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert began probing the edges of consciousness through their experiments with psychedelics. Leary became the LSD guru, challenging convention, questioning authority and as a result spawned a global counter culture movement landing in prison after Nixon called him “the most dangerous man in America”. RAM DASS Ram Dass (born Richard Alpert, April 6, 1931) is an American contemporary spiritual teacher and the author of the seminal 1971 book ‘Be Here Now’. DR. ANDREW WEIL Dr. Andrew Weil is a physician, author, professor and one of the world’s preeminent media celebrities in the field of medicine and personal growth. He is a long-time advocate for both Western medicine and alternative therapies. Dr. Weil graduated from Harvard University where he was also an undergraduate reporter for the Harvard Crimson. His investigative journalism led to Leary & Alpert’s dismissal from Harvard and the unraveling of their University studies in the use of psychoactive drugs for medical research and treatments. HUSTON SMITH Smith’s book “The World’s Religions” has sold over two million copies and remains a popular introduction to comparative religion. Smith, through his friendship with Aldous Huxley, met Leary and Alpert and others at the Center for Personality Research at Harvard. There, Smith was one of the active participants in Leary and Alpert’s early experiments, particularly “the Good Friday Experiment.” He termed the experiments “empirical metaphysics. His book, “Cleansing the Doors of Perception,” describes his experiences. Smith has both studied and practiced Christianity, mysticism, Vedanta, Zen Buddhism and Sufi Islam. -

Full Results of Survey of Songs

Existential Songs Full results Supplementary material for Mick Cooper’s Existential psychotherapy and counselling: Contributions to a pluralistic practice (Sage, 2015), Appendix. One of the great strengths of existential philosophy is that it stretches far beyond psychotherapy and counselling; into art, literature and many other forms of popular culture. This means that there are many – including films, novels and songs that convey the key messages of existentialism. These may be useful for trainees of existential therapy, and also as recommendations for clients to deepen an understanding of this way of seeing the world. In order to identify the most helpful resources, an online survey was conducted in the summer of 2014 to identify the key existential films, books and novels. Invites were sent out via email to existential training institutes and societies, and through social media. Participants were invited to nominate up to three of each art media that ‘most strongly communicate the core messages of existentialism’. In total, 119 people took part in the survey (i.e., gave one or more response). Approximately half were female (n = 57) and half were male (n = 56), with one of other gender. The average age was 47 years old (range 26–89). The participants were primarily distributed across the UK (n = 37), continental Europe (n = 34), North America (n = 24), Australia (n = 15) and Asia (n = 6). Around 90% of the respondents were either qualified therapists (n = 78) or in training (n = 26). Of these, around two-thirds (n = 69) considered themselves existential therapists, and one third (n = 32) did not. There were 235 nominations for the key existential song, with enormous variation across the different respondents. -

Preliminary Syllabus MUS 20: the Poetry and Songs of Leonard Cohen Instructor, T

Preliminary Syllabus MUS 20: The Poetry and Songs of Leonard Cohen Instructor, T. Hampton Recommended book: Cohen, Stranger Music. First Meeting, Oct 11: “Remember me, I used to live for music.” The poet as songwriter. Montréal. The Canadian Scene. Irving Layton. Cohen in Greece: Let Us Compare Mythologies, Songs of Leonard Cohen, Songs from a Room. Key Songs: “Suzanne,” “Sisters of Mercy,” “Stranger Song,” “Bird on the Wire,” “Story of Isaac,” “Seems So Long Ago, Nancy,” “So Long, Marianne.” Themes: flesh and spirit, the identity of the singing voice, abjection and humiliation. Second Meeting, Oct 18: “It’s four in the morning, the end of December.” Cohen in the spotlight. The Chelsea Hotel. Isle of Wight. Cohen on the move. Songs of Love and Hate, New Skin for the Old Ceremony. Key Songs: “Famous Blue Raincoat,” “Joan of Arc,” “Who by Fire,” “A Singer Must Die,” “Take This Longing,” “Dress Rehearsal Rag.” Themes: limits of power, self-doubt, drugs, self-purification, betrayal. Third Meeting, Oct 25: “I will speak no more, till I am spoken for.” Cohen as “The Prince of Bummers.” Death of a Lady’s Man. Death of a Ladies Man. Recent Songs. Various Positions. Key Songs: “If It Be Your Will,” “Hallelujah,” “Coming Back to You.” “The Guests.” “The Smoky Life,” “Dance Me to the End of Love.” Jennifer Warnes, Famous Blue Raincoat. Themes: Humility, divinity, Impotence. Fourth Meeting, Nov. 1: “I was born like this, I had no choice.” Cohen Returns. The importance of the keyboard. New production values. Book of Mercy. Book of Longing. I’m Your Man. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Nietzsche: Looking Right, Reading Left

Educational Philosophy and Theory ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rept20 Nietzsche: Looking right, reading left Babette Babich To cite this article: Babette Babich (2020): Nietzsche: Looking right, reading left, Educational Philosophy and Theory, DOI: 10.1080/00131857.2020.1840974 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1840974 Published online: 16 Nov 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 394 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rept20 EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHY AND THEORY https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1840974 EDITORIAL Nietzsche: Looking right, reading left The far right appropriates a Nietzsche invented out of its own fantasies, likewise the left in its critique of these appropriations, battles a projection cobbled in response to that of the far right. If centrist visions likewise exist, many, for want of likely suspects, relegate these to the left. Indeed, in their lead contribution to their collection on The Far Right, Education, and Violence, Michael Peters and Tina Besley point out that the cottage industry of Nietzsche mis- appropriations, especially those kipped to the right, has been booming for more than a cen- tury (Peters & Besley, 2020, p. 5; cf. Alloa, 2017; Illing, 2018; Kellner, 2019). Beyond the pell-mell of misreadings and prototypically ‘Nazi’ bowdlerization under Hitler, Peters and Besley rightly point out that what they name the “‘pedagogical problem’” (Peters & Besley, 2020, p. 10) can be located at the heart of such a political free for all, on the right as on the left. -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

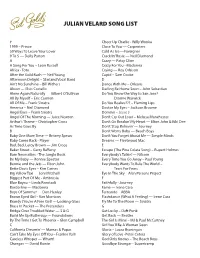

Julian Velard Song List

JULIAN VELARD SONG LIST # Cheer Up Charlie - Willy Wonka 1999 – Prince Close To You — Carpenters 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Cold As Ice —Foreigner 9 To 5 — Dolly Parton Cracklin’ Rosie — Neil Diamond A Crazy — Patsy Cline A Song For You – Leon Russell Crazy For You - Madonna Africa - Toto Crying — Roy Orbison After the Gold Rush — Neil Young Cupid – Sam Cooke Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band D Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Dance With Me – Orleans Alison — Elvis Costello Darling Be Home Soon – John Sebastian Alone Again Naturally — Gilbert O’Sullivan Do You Know the Way to San Jose? — All By Myself – Eric Carmen Dionne Warwick All Of Me – Frank Sinatra Do You Realize??? – Flaming Lips America – Neil Diamond Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Angel Eyes – Frank Sinatra Domino – Jesse J Angel Of The Morning — Juice Newton Don’t Cry Out Loud – Melissa Manchester Arthur’s Theme – Christopher Cross Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart — Elton John & Kiki Dee As Time Goes By Don’t Stop Believin’ — Journey B Don’t Worry Baby — Beach Boys Baby One More Time — Britney Spears Don’t You Forget About Me — Simple Minds Baby Come Back - Player Dreams — Fleetwood Mac Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown — Jim Croce E Baker Street – Gerry Raerty Escape (The Pina Colata Song) – Rupert Holmes Bare Necessities - The Jungle Book Everybody’s Talkin’ — Nilsson Be My Baby — Ronnie Spector Every Time You Go Away – Paul Young Bennie and the Jets — Elton John Everybody Wants To Rule The World – Bette Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes Tears For Fears Big Yellow Taxi — Joni Mitchell Eye In -

The 'New' Heidegger

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Philosophy Collections 1-2015 The ‘New’ Heidegger Babette Babich [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, Other German Language and Literature Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, Radio Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Babich, Babette, "The ‘New’ Heidegger" (2015). Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections. 65. https://fordham.bepress.com/phil_babich/65 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters in Academic Book Collections by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 10 The ‘New’ Heidegger Babette Babich 10.1 Calculating Heidegger: From the Old to the New The ‘new’ Heidegger corresponds less to what would or could be the Heidegger of the moment on some imagined ‘cutting edge’ than it corresponds to what some wish they had in Heidegger and above all in philosophical discussions of Heidegger’s thought. We have moved, we suppose, beyond grappling with the Heidegger of Being and Time . And we also tend to suppose a fairly regular recurrence of scandal—the current instantiation infl amed by the recent publication of Heidegger’s private, philosophical, Tagebücher, invokes what the editor of these recently published ‘black notebooks’ attempts to distinguish as Heidegger’s ‘historial antisemitism’ — ‘historial’ here serving to identify Heidegger’s references to World Jewry in one of the volumes.