Infrastructure Charges: Creating Incentives to Improve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Carbon Footprint of Valencia Port: a Case Study of the Port Authority of Valencia (Spain)

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article The Carbon Footprint of Valencia Port: A Case Study of the Port Authority of Valencia (Spain) Víctor Cloquell Ballester 1 , Vanesa G. Lo-Iacono-Ferreira 2,* , Miguel Ángel Artacho-Ramírez 1 and Salvador F. Capuz-Rizo 1 1 Department of Engineering Projects, Valencia Campus, Universitat Politècnica de València, Camino de Vera, s/n, E-46022 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] (V.C.B.); [email protected] (M.Á.A.-R.); [email protected] (S.F.C.-R.) 2 Department of Engineering Projects, Alcoy Campus, Universitat Politècnica de València, Plaza Ferrándiz y Carbonell, s/n, E-03690 Alcoy, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 September 2020; Accepted: 29 October 2020; Published: 4 November 2020 Abstract: Maritime transport is responsible for 13% of the Greenhouse Gases (GHG) emissions of the transport sector. Port authorities, terminals, shipping companies, and other stakeholders have joined efforts to improve this sector’s environmental performance. In Spain, the Ministry for Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge has developed a methodology to assess the carbon footprint. This methodology has been adapted to ports and applied to processes under the Port Authority of Valencia’s umbrella achieving scopes 1, 2, and 3. The results highlight that ship traffic, within the port, of containers and cruises (categorized in scope 3) had a major impact on the carbon footprint. Buildings lighting managed by the terminals has a significant effect on scope 2. Diesel consumption shares with gasoline consumption the primary representation in scope 1. The carbon footprint between 2008 and 2016 was maintained, although traffic in the port increased by 24% during this period. -

Lakes Port & Harbor: Infrastructure & Dredging Cost Estimate Matrix Tool

Great Lakes Port & Harbor: Infrastructure & Dredging Cost Estimate Matrix Tool and Duluth, MN/Superior, WI and Toledo, OH Case Studies Gene Clark1 and Dale Bergeron2 1 WI Sea Grant [email protected] 2 MN Sea Grant dbergeron@ d.umn.edu Defining the parameters of the Matrix Great Lakes ports, harbors and marinas are vulnerable to several potential climate change impacts. The two major impacts most relevant and potentially most costly are water level and storm intensity. Both rising and falling water levels can impact infrastructure stability and overall strength, as well as requiring additional channel dredging. A climatic change resulting in an increase in severe storms (more precipitation, higher winds and greater number of storm events) is also viewed as having detrimental affects on infrastructure. More severe storms can create larger waves, more extreme Seiche events and greater storm-surges that can damage port and harbor infrastructure requiring costly rehabilitation or replacement. In addition to infrastructure issues, an increased storm frequency and intensity will increase channel silting and sedimentation, compounding dredging problems analogous to lower water level scenarios. Climate model predictions for specific weather outcomes vary greatly throughout the Great Lakes Basin, and include both higher and lower water levels scenarios. However, all predictions seem to include an increase in both the number and intensity of major storm events. This combination can result in unanticipated water level change, larger waves, more dramatic Seiches and greater storm surges than considered in original design parameters (all of this in addition to the antiquated and sometime dilapidated state of our Great Lakes infrastructure). -

All Aboard: the Aggregate Effects of Port Development

All aboard: The aggregate effects of port development César Ducruet1, Réka Juhász2, Dávid Krisztián Nagy3, and Claudia Steinwender4 1CNRS 2Columbia University 3CREI, Universitat Pompeu Fabra and Barcelona GSE 4MIT Sloan ∗ July 3, 2019 Abstract This paper studies the distributional and aggregate economic effects of new port technologies developed in the second half of the 20th century. We show that new technologies have led to a significant reallocation of shipping activity from large to small cities. This was driven by a land price mechanism; as new port technologies are more land-intensive, ports moved from large, high land price cities to smaller, lower land price ones. We add endogenous port development to a standard quantitative model of cross- city trade to account for both the benefits and the costs of port development. According to the model, the adoption of new port technologies leads to benefits through increasing market access but is costly, requiring the extensive use of land, suggesting a reallocation of shipping activities towards cities with low land prices and thus net gains from new port technologies that are heterogeneous across cities. Counterfactual results suggest that new port technologies led to sizable aggregate gains for the world economy, with substantial heterogeneity in the effects across countries. More generally, accounting for the costs of port infrastructure development endogenously has the potential to alter the size and distribution of the gains from trade. ∗We thank David Atkin, Don Davis, Dave Donaldson, Joseph Doyle, Matt Grant, Gordon Hanson, Tom Holmes, Amit Khandelwal, Jim Rauch, Roberto Rigobon, Esteban Rossi-Hansberg and Tavneet Suri for helpful comments and discussions. -

Medcruise Newsletter Issue 52 Nov 2016.Qxp 22/11/2016 14:48 Page 1

MedCruise Newsletter Issue 52 Nov 2016.qxp 22/11/2016 14:48 Page 1 MedCruise News MedCruise members discuss November 2016 “Guidelines for Cruise Terminals” Issue 52 MedCruise News pg. 1-7 Barcelona), Chairman of the Port facilities & PIANC International Destinations pg. 8-22 Working Group that developed this major project over the course of the last Meet the MedCruise four years, revealed members pg. 23 to the MedCruise membership the just completed study List of MedCruise that embodies a Members pg. 24 flexible design approach so that terminals can be adapted to the various current and and ground transportation area. future needs of In view of the importance to the cruise n Friday, September 23rd, MedCruise cruise companies. industry of port security and operational and members had an excellent opportunity Following the presentation, MedCruise financial aspects, special emphasis has been to discuss best strategies to invest in members had the opportunity to engage in an laid on these two topics. O extended Q&A session, while each member This report has been drafted by an cruise terminals, during a special session held in Santa Cruz de Tenerife on the occasion of also received a copy of the study that provides international working group (WG 152) set up Seatrade Cruise Med 2016. technical guidelines for assisting the by PIANC in 2012. The main objective of the During the session, MedCruise members also development of cruise port facilities. Based on work was to provide a guideline for the discussed in detail the results of the most the newest trends in cruise ships and the functional design of cruise terminals, by recent PIANC study on cruise terminals industry in general, the document covers all reviewing the needs of modern cruise ships investment, planning & design. -

Lectures 13 to 15 CHAPTER 3: PUBLIC GOODS

Lectures 13 to 15 CHAPTER 3: PUBLIC GOODS 3.1: Public Goods Pure Private to Pure Public Good • Private good consumed only by one person: food, holidays, clothes • Family/household: all collective decisions and no market. ‘Micro- collective’. Share kitchens, TV, bathrooms. • Many families/household: roads and paths, communal halls, clubs etc. Tennis and golf clubs, plus Tidy Towns’ committees for example. ‘Mini- collective’. • Option public goods: fire brigade, hospitals, museums, etc. Provided by state but not used by all. ‘Partial full collective’ • Pure public goods benefit ALL. ‘Full collective’. National security, environment, lakes, sea and mountains. Used by all but to varying degrees. • Exclusion impossible. Raises free-rider problem: e.g. lighthouse, but now excludable. Firework display a good example (see later) • Public goods bring benefits just like private goods: Ui = F(A, B, C, D) • Same supply for ALL: G1=G2=G3= etc. Not same utility though. • Private good, A; same price and utility but different supply • Pure v impure PGs: security v bridge (Fig 3.1) • Fire brigade example (p. 144). Available to all, but only used when needed if ever. Private company would protect only those how had paid. • Public goods v natural monopolies (e.g. electricity or water) but private A fireworks display is a public good because it is non-excludable (impossible to prevent people from viewing it) and non-rivalrous (one individual's use does not reduce availability to others). Voluntary payment (Fig 3.3) • MC curve same as that for private goods (Fig 3.3): n people benefit though from every extra unit. -

Public Goods for Economic Development

Printed in Austria Sales No. E.08.II.B36 V.08-57150—November 2008—1,000 ISBN 978-92-1-106444-5 Public goods for economic development PUBLIC GOODS FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT FOR ECONOMIC GOODS PUBLIC This publication addresses factors that promote or inhibit successful provision of the four key international public goods: fi nancial stability, international trade regime, international diffusion of technological knowledge and global environment. Each of these public goods presents global challenges and potential remedies to promote economic development. Without these goods, developing countries are unable to compete, prosper or attract capital from abroad. The undersupply of these goods may affect prospects for economic development, threatening global economic stability, peace and prosperity. The need for public goods provision is also recognized by the Millennium Development Goals, internationally agreed goals and targets for knowledge, health, governance and environmental public goods. Because of the characteristics of public goods, leaving their provision to market forces will result in their under provision with respect to socially desirable levels. Coordinated social actions are therefore necessary to mobilize collective response in line with socially desirable objectives and with areas of comparative advantage and value added. International public goods for development will grow in importance over the coming decades as globalization intensifi es. Corrective policies hinge on the goods’ properties. There is no single prescription; rather, different kinds of international public goods require different kinds of policies and institutional arrangements. The Report addresses the nature of these policies and institutions using the modern principles of collective action. UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. -

Early Warning System Secures Spanish Ports

CASE STUDY TETRA AND SCADA SOLUTIONS KEEPING SPANISH PORTS SAFE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM SECURES SPANISH PORTS COMBINED TETRA AND SCADA SOLUTION PROMOTES SAFER MARITIME TRADE To safeguard the handling of potentially hazardous cargo along one of the CUSTOMER PROFILE Company: Mediterranean’s primary shipping routes, the Port Authority of Valencia (PAV) has Port Authority of Valencia, Ministry of Development, installed a resilient, automated early warning system. Government of Spain The solution has been integrated into a Dimetra IP Compact TETRA and Motorola Industry Name: Ports and Harbours MOSCAD/ACE3600 RTU network, covering approximately 80 kilometres of Spain’s Motorola Solutions Partners: eastern coastline. It connects the three state-owned ports of Valencia, Sagunto ANFER Radiocomunicaciones (ANFER and Gandia, which are managed and administered by the PAV. Strategically located F.P.C., S.L.) near the Straits of Gibraltar, these ports play a pivotal role in the shipping of goods Key Benefits: • Fully integrated SCADA solutions between America, the Mediterranean Basin and the Far East. into TETRA network • Enhanced voice and data communications The Port of Valencia has a big impact on the state economy, generating more than • Highly reliable, scalable and robust • Cost-effective: single network for 15,000 working places and over 1.1 billion Euros of revenue. During 2010, over voice and data 64 million tons of containerised cargo passed through its ports and the number of Product Name: passengers has escalated to over 470,000 annually. • Motorola Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition (SCADA) system • ACE3600 Remote Terminal Units The Port of Valencia also provides vital road and rail connections for the distribution and ACE3600 Front End Processor • Dimetra IP Compact TETRA of goods to southern Europe and North Africa. -

Port Expansion and Negative Externalities: Estimating the Costs Borne by Local Residents

Port expansion and negative externalities: estimating the costs borne by local residents Salvador del Saz-Salazar1, Leandro García-Menéndezb,1 a Department of Applied Economics II, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain, Email: [email protected] b Department of Applied Economics II, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Port expansion has been seen as the origin of negative externalities affecting local residents’ wellbeing and contributing to the poor public image of ports. In this study the contingent valuation method is used to estimate the costs borne by local residents as a consequence of the negative externalities derived from the growth of the Port of Valencia (Spain) in the last thirty years. Although the current practice is to use the willingness to pay measure to value both gains and losses, in this case it was deemed more appropriate to use the willingness to accept (WTA) measure given the perceived property rights. The econometric analysis undertaken reveals that WTA is positively related to the bid offered and negatively related to family income, as expected. Among the different externalities derived from this growth, the only concern that affects individuals’ WTA is the reclamation of land from the sea. Finally, the results obtained show that the present value of the costs potentially borne by local residents ranges from a minimum value of €64.4 million to a maximum value of €107.4 million depending of the aggregation criterion chosen. Key Words: Contingent valuation, willingness to accept, port expansion, negative externalities, land reclamation. JEL code: Q51. 1. Introduction Throughout history seaports have played a vital role in promoting the economic development and prosperity of nations. -

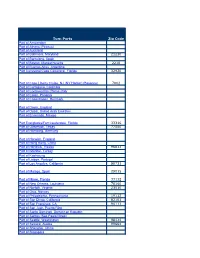

Port of Amsterdam Port of Athens (Piraeus) Port of Auckland Port Of

Turn Ports Zip Code Port of Amsterdam Port of Athens (Piraeus) Port of Auckland Port of Baltimore, Maryland 21230 Port of Barcelona, Spain Port of Boston, Massachusetts 2210 Port of Buenos Aires, Argentina Port Canaveral/Cape Canaveral, Florida 32920 Port of Cape Liberty Cruise, NJ (NY Harbor) (Bayonne) 7002 Port of Cartagena, Colombia Port of Civitavecchia (Rome) Italy Port of Colon, Panama Port of Copenhagen, Denmark Port of Dover, England Port of Dubai, United Arab Emirates Port of Ensenada, Mexico Port Everglades/Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33316 Port of Galveston, Texas 77550 Port of Hamburg, Germany Port of Harwich, England Port of Hong Kong, China Port of Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Port of Istanbul, Turkey Port of Kaohsiung Port of Lisbon, Portugal Port of Los Angeles, California 90731 Port of Malaga, Spain 29015 Port of Miami, Florida 33132 Port of New Orleans, Louisiana 70160 Port of Norfolk, Virginia 23510 Port of Oslo, Norway Port of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19112 Port of San Diego, California 92101 Port of San Francisco, CA 94111 Port of San Juan, Puerto Rico Port of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic Port of Santos (Sao Paulo) Brazil Port of Seattle, Washington 98134 Port of Seward, Alaska 99664 Port of Shanghai, China Port of Singapore Port of Southampton, England Port of Stockholm, Sweden Port of Sydney, Australia Port of Tampa, Florida 33602 Port of Tianjin, China Port of Valencia TBA Port of Valparaiso, Chile Port of Vancouver (Ballantyne Pier & Canada Place Pier) Port of Venice, Italy Approxi to the DISTANCIA Port in EN KM Closest Airport Miles* Schipol International (AMS) 13 20.8 Athens Elefterios Venizelos International (ATH) 50 80 Aucklund International (AKL) 14 22.4 Baltimore/Washington International (BWI) 11 17.6 El Prat International (BCN) 10 16 Logan International (BOS) 4 6.4 Ministro Ezeiza International Airport (EZE) 18 28.8 Orlando International (MCO) 46 73.6 Newark Liberty International (EWR) 9 14.4 LaGuardia International (LGA) 20.5 32.8 John F. -

Shipping Emissions in the Iberian Peninsula and Its Impacts on Air Quality Rafael A.O

Shipping emissions in the Iberian Peninsula and its impacts on air quality Rafael A.O. Nunes1, Maria C.M. Alvim-Ferraz1, Fernando G. Martins1, Fátima Calderay-Cayetano2, Vanessa Durán-Grados2, Juan Moreno-Gutiérrez2, Jukka-Pekka Jalkanen3, Hanna Hannuniemi3, Sofia 5 I.V. Sousa1 1LEPABE – Laboratory for Process Engineering, Environment, Biotechnology and Energy, Faculty of Engineering, University of Porto, Rua Dr. Roberto Frias, 4200-465, Porto, Portugal 2Departamento de Máquinas y Motores Térmicos, Escuela de Ingenierías Marina, Náutica y Radioelectrónica, Campus de Excelencia Internacional del Mar (CEIMAR), Universidad de Cádiz, Spain 10 3Finnish Meterological Institute, P.O. Box 503, 00101 Helsinki, Finland Correspondence to: Sofia I.V. Sousa ([email protected]) Abstract. Marine traffic has been identified as a relevant source of pollutants, which cause known negative effects on air quality. The Iberian Peninsula is a central point in the connection of shipping traffic between the Americas and Africa and the rest of Europe. To estimate the effects of shipping emissions inland and around the Iberian Peninsula, EMEP MSC-W model 15 was run considering and not considering shipping emissions (obtained with STEAM3 model). Total estimated emissions of CO, CO2, SOx, NOx and particulate matter (subdivided in elementary carbon (EC), organic carbon (OC), sulphate and ash) for the study domain in 2015 were, respectively, 49 ktonnes y-1, 30000 ktonnes y-1, 360 ktonnes y-1, 710 ktonnes y-1, 4.5 ktonnes -1 -1 -1 -1 y , 11 ktonnes y , 32 ktonnes y and 3.3 ktonnes y . Shipping emissions increased SO2 and NO2 concentrations especially near port areas and also increased the O3, sulphate, and particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) concentrations around all over the 20 Iberian Peninsula coastline (especially in the south coastal region). -

Central New York Inland Port Market Feasibility Study

FINAL REPORT CENTRAL NEW YORK INLAND PORT MARKET FEASIBILITY STUDY potenti PREPARED FOR: NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION SUBMITTED BY: RSG CENTRAL NEW YORK INLAND PORT MARKET FEASIBILITY STUDY PREPARED FOR: NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 1 Purpose and Background ................................................................................................................ 1 Principal Findings ............................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND .......................................................................................... 6 2.1 | Physical Requirements .................................................................................................................. 6 2.2 | Central New York Inland Port Proposals: History ......................................................................... 7 3.0 INFORMATION SOURCES .............................................................................................................. 8 4.0 TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE AND OPERATIONS .................................................. 10 4.1 | Rail Service ................................................................................................................................. 10 4.2 | Highway ...................................................................................................................................... -

Port Infrastructure Development Grants and Port Planning And

Port Infrastructure Development Grants and Port Planning and Investment Toolkit Norfolk, VA AAPA Oct 14, 2019 Travis Black Port Infrastructure Development Program Team Office of Ports & Waterways Planning Maritime Administration 1200 New Jersey Ave., SE | Washington | DC 20590 w w w . d o t . g o v U.S. Transportation System Overview • The transportation system moved 17.7 billion tons of goods valued at over $18.1 trillion in 2016.(1) • Trucks carried 62.7 percent of the tonnage, 11.1 billion tons, and 61.9 percent of the value. • Rail moved 1.6 billion tons, 8.9 percent of goods, and water moved 0.8 billion tons, or 4.5 percent, in 2016. Remainder was carried by air, pipeline, or a combination of modes. • Goods valued at $527 billion moved on all waterways of the United States. • Transportation’s contribution to the U.S. GDP was $1,066.9 billion in 2016 according to the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS).(2) • For-hire transportation contributed $562.4 billion or 2.97 percent to the U.S. GDP. • In-house transportation contributed another $504.5 billion or 2.66 percent. • Inland water transportation contributed $19.2 billion to U.S. GDP. • For-hire water transportation contributed $16.5 billion and in-house contributed $2.8 billion.(3) (1)Transportation Statistics Annual Report, 2018. U.S. Department of Transportation Bureau of Transportation Statistics. (2)In-house transportation is business-related transportation. Business-related transportation includes privately owned and operated vehicles of all body types, used primarily on public rights of way, and the supportive services to store, maintain, and operate those vehicles.