Vic Election Lib IBAC Backgrounder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

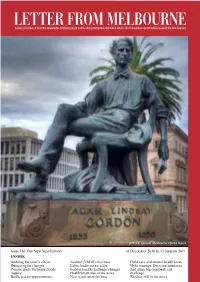

Letter from Melbourne Is a Monthly Public Affairs Bulletin, a Simple Précis, Distilling and Interpreting Mother Nature

SavingLETTER you time. A monthly newsletter distilling FROM public policy and government decisionsMELBOURNE which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. Saving you time. A monthly newsletter distilling public policy and government decisions which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. p11-14: Special Melbourne Opera insert Issue 161 Our New Year Edition 16 December 2010 to 13 January 2011 INSIDE Auditing the state’s affairs Auditor (VAGO) also busy Child care and mental health focus Human rights changes Labor leader no socialist. Myki musings. Decision imminent. Comrie leads Victorian floods Federal health challenge/changes And other big (regional) rail inquiry HealthSmart also in the news challenge Baillieu team appointments New water minister busy Windsor still in the news 16 DECEMBER 2010 to 13 JANUARY 2011 14 Collins Street EDITORIAL Melbourne, 3000 Victoria, Australia Our government warming up. P 03 9654 1300 Even some supporters of the Baillieu government have commented that it is getting off to a slow F 03 9654 1165 start. The fact is that all ministers need a chief of staff and specialist and other advisers in order to [email protected] properly interface with the civil service, as they apply their new policies and different administration www.letterfromcanberra.com.au emphases. These folk have to come from somewhere and the better they are, the longer it can take for them to leave their current employment wherever that might be and settle down into a government office in Melbourne. Editor Alistair Urquhart Some stakeholders in various industries are becoming frustrated, finding it difficult to get the Associate Editor Gabriel Phipps Subscription Manager Camilla Orr-Thomson interaction they need with a relevant minister. -

AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

Dungog Chronicle office (NSW), ca early 1900s. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 52 May 2009 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, 59 Emperor Drive, Andergrove, Qld, 4740. Ph. 61-7-4955 7838. Email: [email protected] Contributing editors are Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, and Barry Blair, of Tamworth. Deadline for the next Newsletter: 15 July 2009. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] The Newsletter is online through the ‘Publications’ link of the University of Queensland’s School of Journalism & Communication Website at www.uq.edu.au/sjc/ and through the ePrint Archives at the University of Queensland at http://espace.uq.edu.au/) New ANHG books/CDs on sale – see final page 1 – CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS: NATIONAL & METROPOLITAN 52.1.1 REVERSE TAKEOVER OF FAIRFAX MEDIA COMPLETED Rural Press Ltd‟s reverse takeover of Fairfax Media Ltd has been completed. Brian McCarthy, as Fairfax CEO, has put former Rural Press executives in charge of the major areas of Fairfax. McCarthy was Rural Press CEO under chairman John B. Fairfax, who is now the biggest single Fairfax Media shareholder. In the new regime, Fairfax Media‟s metropolitan mastheads will take over responsibility for its key online classified brands as part of McCarthy‟s move to more closely integrate the group‟s print and internet advertising revenue models. The management restructure seeks to position the group more along functional lines and less on geographic lines. McCarthy has abolished his own former position as Fairfax deputy chief executive and head of Australian newspapers. -

2010 Victorian State Election Summary of Results

2010 VICTORIAN STATE ELECTION 27 November 2010 SUMMARY OF RESULTS Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Legislative Assembly Results Summary of Results.......................................................................................... 3 Detailed Results by District ............................................................................... 8 Summary of Two-Party Preferred Result ........................................................ 24 Regional Summaries....................................................................................... 30 By-elections and Casual Vacancies ................................................................ 34 Legislative Council Results Summary of Results........................................................................................ 35 Incidence of Ticket Voting ............................................................................... 38 Eastern Metropolitan Region .......................................................................... 39 Eastern Victoria Region.................................................................................. 42 Northern Metropolitan Region ........................................................................ 44 Northern Victoria Region ................................................................................ 48 South Eastern Metropolitan Region ............................................................... 51 Southern Metropolitan Region ....................................................................... -

THE FAMOUS FACES WHO HELPED INSPIRE a GREAT KNIGHT for the Past 25 Years, GRANT Mcarthur Keating and Malcolm Hewitt Screaming “C’Mon”

06 NEWS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 8, 2015 HERALDSUN.COM.AU ALWAYS MAKING HEADLINES Melbourne legends, stars mark our milestone IT was aptly a headline- NUI TE KOHA, outed him and then-girlfriend a great move and it’s just gone grabbing event celebrating the JACKIE EPSTEIN Holly before they had gone on from strength to strength. I’m 25-year milestone of a news AND LUKE DENNEHY a second date. really honoured to be part of powerhouse. “We hadn’t had that chat,” this celebration ... It’s such a big About 350 prominent Mel- Television legend Newton Hughes said. part of Melbourne.” burnians gathered to honour said: “Melbourne is a great city Holly, a journalist, started Celebrity guests were in a the Herald Sun at a star-stud- but it’s made even better by working at the Herald Sun as a cheeky mood when photogra- ded party at The Emerson in institutions like the Herald Sun. “beautiful 22 year old,” he said. phers tried to get a shot of the South Yarra last night. “I can’t imagine Melbourne “For 10 years, not one editor assembled throng. Powerbrokers, including without it. hit on her. What is going on “(Jeff) Kennett will break Eddie McGuire, Michael Gud- “I’m a Melbourne boy, born there?” Hughes said. the camera,” John Elliott bel- inski, Jeanne Pratt, Robert and bred, and the Herald Sun is He said media mogul Ru- lowed. Doyle and Jeff Kennett, joined one of the important traditions pert Murdoch insisted Colling- Kennett retorted: “The legends, like Ian “Molly” Mel- of living here.” wood”s 1990 premiership win camera will break itself. -

Appendix 6 Ted Baillieu, Former Victorian Premier, Calls for Ban On

Appendix 6 MEDIA COVERAGE OF ACHRH CAMPAIGN TO BAN DOWRY IN AUSTRALIA Parliament tabling of petition and Media Coverage Petition to make dowry illegal by calling it economical abuse under the FV Legislation 2008 was initiated by ACHRH. The petition has been signed by 600 people so far. It has been tabled TWICE in the Victorian Parliament by Ted Baillieu. - on 13 March 2014 and 26 June 2014 The petition is currently active and attached . Ted Baillieu, former Victorian premier, calls for ban on marriage dowries Updated 23 May 2014, 1:36pm http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-05-23/ted-baillieu-calls-for-dowry-ban/5472710 Dowry's dark shadow Date May 23, 2014 Rachel Kleinman Indian women living in Australia suffer domestic violence stemming from a tradition that some say should be outlawed. http://www.smh.com.au/world/dowrys-dark-shadow-20140522-38ris.html Former Victorian Premier Ted Baillieu is leading a push for a ban on brides being forced to bestow valuable dowries on their husbands. By GARETH BOREHAM Source: 23 May 2014 - 7:12 PM UPDATED 23 May 2014 - 8:37 PM http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2014/05/23/renewed-call-ban-dowries-australias-indian-communities Dowry's dark side: 'Mental, physical, financial abuse' Peggy Giakoumelous 26 Jun 2014 - 4:32pm http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2014/06/26/dowrys-dark-side-mental-physical-financial- abuse Australians falling victim to dowry abuse Updated 5 July 2014, 21:25 AEST Australia Network News Dowry extortion is a long standing problem in India and Pakistan, but now it appears to be on the rise in Australia. -

International Education Summit 21-23 September 2020

INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION SUMMIT 21-23 SEPTEMBER 2020 In collaboration with ATN INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION SUMMIT WRAP UP INTRODUCTION As Australia’s fourth-largest export industry, and a driver of our economic, social and diplomatic success, International Education is now more important than ever. Now that it is under threat from a perfect storm of local and global headwinds, it is crucial to carefully consider its future. The Australian Technology Network of Universities Mayor Sally Capp, The Hon Ted Baillieu AO, The Hon (ATN) organised the International Education Summit Senator Penny Wong, The Hon Alexander Downer to explore international education’s impact and AC and The Hon Stephen Smith. Minister for Trade, discuss its future. The online Summit brought together Tourism and Investment, The Hon Simon Birmingham university leaders, current and former political MP, opened the Summit, and Minister for Education, the leaders, international students, and representatives Hon Dan Tehan MP closed proceedings. The Summit’s from industries such as tourism, rural and regional final day included broadcasting the signing of our development and small business. All of these groups memorandum of understanding with the Philippines benefit immensely from international education in Commission for Higher Education, hosted by University Australia, be it through students working in hard-to- of Technology Sydney Vice Chancellor and ATN Chair, fill jobs in regional areas, the cultural and intellectual Professor Attila Brungs. diversity international students bring to classrooms and workplaces, or the diplomatic benefit they provide The Summit received a large volume of news coverage as advocates for Australia when back in their home spread across national, international and community countries. -

1987 Queensland Cabinet Minutes Queensland State Archives

1987 Queensland Cabinet Minutes Queensland State Archives 1987 timeline 1 November 1986 National Party wins election in its own right ( 1983 relied upon defection of two Liberals) 12 January 1987 Phil Dickie article in the Courier Mail in which he identifies two main groups running Queensland’s thriving sex industry. 31 January 1987 Bjelke-Petersen launches Joh for PM campaign at Wagga Wagga. 7 February 1987 Bjelke-Petersen reported in Courier Mail as saying PM job ‘down the road’. 13 February 1987 Meeting between Ian Sinclair (federal parliamentary leader of the National Party) and Bjelke-Petersen. Lasted only 30 mins and Bjelke-Petersen refused to call a ‘truce’ with the federal LNP opposition. He also addressed public meeting in Alice Springs claiming it as the venue where the ‘war’ began…as opposed to Wagga Wagga where the Joh for PM campaign was launched. 21 February 1987 The Courier Mail reports on the Savage Committee report on red tape reduction before Cabinet – recommending a formal review of Local Government Act with representatives of Public Service Board, LGA, BCC, Urban Development Institute & Queensland Confederation of Industry. In a separate article, Lord Mayor Atkinson supports findings of Savage Report. 27 February 1987 Queensland National Party Central Council voted to withdraw from federal coalition. ( Courier Mail 28/2/87) 14 March 1987 Courier Mail reports Queensland has highest unemployment rate, lowest job vacancy rate, highest fall in residential building starts (Senator Garry Jones (ALP)) 5 April 1987 Advertisement depicting the Grim Reaper knocking down a diverse range of people like pins in a bowling alley was first screened , kicking off the Commonwealth’s public response to the AIDS epidemic 10 April 1987 National Party Queensland, State Management Committee ordered Queensland’s federal members to leave the coalition. -

Vic Libs Reeling Over Secret Baillieu Tape PUBLISHED: 24 JUN 2014 12:38:00 | UPDATED: 25 JUN 2014 05:58:53

Vic Libs reeling over secret Baillieu tape PUBLISHED: 24 JUN 2014 12:38:00 | UPDATED: 25 JUN 2014 05:58:53 LUCILLE KEEN AND MATHEW DUNCKLEY An embarrassing leaked recording of former Victorian premier Ted Baillieu criticising other Liberal MPs to journalists has inflamed tensions in the party. In the recording of a conversation with an Age journalist Mr Baillieu slammed the factional divides which led to the selection of Tim Smith to contest the blue-ribbon seat of Kew at the next election. Mr Baillieu supported front bencher Mary Wooldridge in her unsuccessful tilt for the seat. Mr Baillieu also criticises MPs Michael Gidley and Murray Thompson and the conservative faction that overturned Denis Napthine as opposition leader in 2002 to be replaced by Robert Doyle. “The technique with Michael Gidley was the technique with Tim Smith,” Mr Baillieu said. He also criticised balance-of-power MP Geoff Shaw. Mr Shaw quit the parliamentary Liberal Party, citing a lack of faith in the leadership, contributing to Mr Baillieu’s resignation hours later. “Shaw has been sponsored into his position by a bunch of people from the very first day led by Bernie Finn and some crazy mates in the parliamentary team and a very senior member of the organisation who is very close to [federal MP] Kevin Andrews,” he said. Mr Shaw said Mr Baillieu can hold his own opinions but the “sad thing is he didn’t allow” his backbenchers any opinions while he was premier. He said claims about his backers were false and he was in a safe Liberal seat, “he takes for granted”. -

Letter from Melbourne

14 FEBRUARY to 23 MARCH 2011 14 Collins Street EDITORIAL Melbourne, 3000 Victoria, Australia Our new government settling in. P 03 9654 1300 Architects are planners. They bring together many issues. F 03 9654 1165 Modern issues. And some history. The architect premier [email protected] of the newish Victorian government has the professional, www.letterfrommelbourne.com.au business, personal, and political and government experiences to design good things. Editor Alistair Urquhart 27 February. One hundred days of the new government. Associate Editor Gabriel Phipps Reviews continue for transport ticketing systems, the Sub-Editor RJ Stove Subscription Manager Camilla Orr-Thomson Healthsmart project and other spending projects of the Advertising Manager Eddie Mior former government, the latter will be more fully explained Editorial Consultant Rick Brown to us all in the Budget on 3 May. Design Richard Hamilton Several ministers are being kept busy in the budget Letter From Melbourne is a monthly public affairs kitchen, slicing and dicing their way through departmental bulletin, a simple précis, distilling and interpreting demands and dreams, and the government’s own public policy and government decisions, which affect business opportunities in Victoria and Australia. election promises. An important distraction from their own specific portfolios. Written for the regular traveller, or people with meeting-filled days, you only have to miss reading The budgetary process is bringing strong focus on industrial relations. Teachers, police, community The Age or The Herald Sun twice a week to need workers, other civil servants, to date, are perhaps looking towards less pay than the (newish) Letter from Melbourne. -

Minister Topples 70-Metre Tower

The Age 16/05/2002 Minister topples 70-metre tower RoyceMillar The president of the Queen Victoria Market Retail Traders Planning Minister Mary Dela- Association, Michael Presser, hunty has refused to approve a also welcomed the decision. 70-metre residential tower that "I'm hoping that the developers would have overshadowed the will come back with something Queen Victoria Market. more appropriate," he said. "This Developer Australian Super is a sensitive area and requires Developments had proposed to sensitive handling." build a $60 million tower on the Carlton Residents Association corner of Victoria and Leicester president Sue Chambers said Streets, the site of the former Victoria Street should be seen as CUB headquarters. a visual boundary between The proposal would have South Carlton and the CBD. been twice the recommended ASD is the development arm height limit under the City of of construction industry super- Melbourne planning scheme. annuation fund Cbus. It would In a letter to the developers, not comment on the refusal. Ms Delahunty said the tower Cbus and ASD are believed to be would overshadow important working with construction group pedestrian areas. Multiplex on a new nine-level The project, designed by office building for the site. architects Robert Peck von Har- The Victorian Civil and Admin- tel Trethowan, drew opposition istrative Tribunal has upheld from market traders, Carlton Melbourne City Council's rejec- residents and the Melbourne tion of a plan to redevelop the City Council. MCG Hotel in Wellington Parade, The council's planning com- East Melbourne. PCH Mel- mittee chairwoman, Catherine bourne planned to demolish the Ng, welcomed the decision. -

Griffith University – Tony Fitzgerald Lecture and Scholarship Program

Griffith University – Tony Fitzgerald Lecture and Scholarship Program THE FITZGERALD COLLECTION An Exhibition of artwork and memorabilia Queensland College of Art College Gallery, Tribune Street, South Bank 29 July 2009 – 9 August 2009 Recollections and Stories The Griffith University – Tony Fitzgerald Lecture and Scholarship Program looks forward, with a biennial public lecture and scholarship program aimed at building skills and awareness in future practitioners and researchers who will carry the responsibility for protecting our future system of parliamentary democracy. For this inaugural year, it is useful to glance backwards, to explore how those now acknowledging this 20th anniversary year, remember this period of our history and how it contributed to the experiences of academics and researchers, artists and public expression. The exhibition focuses on Mr Fitzgerald’s personal collection of memorabilia and the influence that the Inquiry had upon Griffith University’s staff and alumni. The stories and commentary in the pages that follow have been provided by those associated in some way with Mr Fitzgerald’s items, or with Griffith University. They represent only a small sample of Queensland’s collective memory. The additional pages following include recollections and stories to accompany the exhibits and, during the exhibition period, can be found on the Key Centre for Ethics, Law, Justice and Governance website: http://www.griffith.edu.au/tonyfitzgeraldlecture We know that there are other recollections and memorabilia not included in this collection, but which are a vital contribution to our social history. The State Library of Queensland is starting a specific collection to capture materials and stories from this period and we urge Queenslanders to make contact with SLQ to ensure that their items and memories can be included for future generations. -

PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE VICTORIA Annual Report to the Minister 2011–2012

PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE VICTORIA Annual Report to the Minister 2011–2012 A report from the Keeper of Public Records as required under section 21(1) of the Public Records Act 1973 VPRS 10742-P000-A31 CONTENTS WELCOME TO PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE VICTORIA Ted Baillieu MLA Premier and Minister for the Arts 3 Public Record Office Victoria 39 Appendices 6 Purpose and Objectives 40 Appendix 1: Assets, financial Purpose: statement and staff profile 7 Message from the Director 41 Appendix 2: Publications To support 9 Public Records Advisory Council 42 Appendix 3: Standards and 10 Overview Advice issued the effective 15 Report on performance 43 Appendix 4: Approved Public Record Office Victoria Storage management and 16 Highlights 2011–2012 Suppliers (APROSS) The Hon Ted Baillieu MLA 27 Output measures 2011–2012 44 Appendix 5: Approved Places use of the public Premier and Minister for the Arts 28 Strategic initiatives 2011–12 of Deposit for temporary Parliament House 28 Remodel the transfer service records records of the Melbourne VIC 3002 28 Refresh VERS 45 Appendix 6: VERS-compliant 29 Enhance Public Record Office products State of Victoria, Victoria’s Standards 46 Appendix 7: 2011 Sir Rupert 29 Expand Public Record Office Hamer Records Management in order that Victoria’s Policy Framework Award Winners Dear Minister 30 Build Collection Support 48 Appendix 8: 2011 Victorian the government 32 Promote Collection Usage Community History Award I am pleased to present a report on the carrying out of my functions under section 36 Foster an IM Culture Winners is accountable 21(1) of the Public Records Act 1973 for the year ending 30 June 2012.