Carceral Camouflage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breaking Open the Sexual Harassment Scandal

Nxxx,2017-10-06,A,018,Cs-4C,E1 , OCTOBER 6, 2017 FRIDAY NATIONAL K THE NEW YORK TIMES 2017 IMPACT AWARD C M Y N A18 Claims of Sexual Harassment Trail a Hollywood Mogul From Page A1 clined to comment on any of the settle- ments, including providing information about who paid them. But Mr. Weinstein said that in addressing employee con- cerns about workplace issues, “my motto is to keep the peace.” Ms. Bloom, who has been advising Mr. Weinstein over the last year on gender and power dynamics, called him “an old dinosaur learning new ways.” She said she had “explained to him that due to the power difference between a major studio head like him and most others in the in- dustry, whatever his motives, some of his words and behaviors can be perceived as Breaking Open the Sexual inappropriate, even intimidating.” Though Ms. O’Connor had been writ- ing only about a two-year period, her BY memo echoed other women’s com- plaints. Mr. Weinstein required her to have casting discussions with aspiring CHRISTOPHER actresses after they had private appoint- ments in his hotel room, she said, her de- scription matching those of other former PALMERI employees. She suspected that she and other female Weinstein employees, she wrote, were being used to facilitate li- Late Edition Harassment Scandal aisons with “vulnerable women who Today, clouds and sunshine, warm, hope he will get them work.” high 78. Tonight, mostly cloudy, The allegations piled up even as Mr. mild, low 66. Tomorrow, times of Weinstein helped define popular culture. -

SOTO-DISSERTATION-2018.Pdf (1.424Mb)

CHICAN@ SOCIOGENICS, CHICAN@ LOGICS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHICAN@ PHILOSOPHY: RUPTURING THE BLACK-WHITE BINARY AND WESTERN ANTI-LATIN@ LOGIC A Dissertation by ANDREW CHRISTOPHER SOTO Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Tommy Curry Committee Members, Gregory Pappas Amir Jaima Marlon James Head of Department, Theodore George May 2018 Major Subject: Philosophy Copyright 2018 Andrew Christopher Soto ABSTRACT The aim of this project is to create a conceptual blueprint for a Chican@ philosophy. I argue that the creation of a Chican@ philosophy is paramount to liberating Chican@s from the imperial and colonial grip of the Western world and their placement in a Black-white racial binary paradigm. Advancing the philosophical and legal insight of Critical Race Theorists and LatCrit scholars Richard Delgado and Juan Perea, I show that Chican@s are physically, psychologically and institutionally threatened and forced by gring@s to assimilate and adopt a racist Western system of reason and logic that frames U.S. institutions within a Black-white racial binary where Chican@s are either analogized to Black suffering and their historical predicaments with gring@s or placed in a netherworld. In the netherworld, Chican@s are legally, politically and socially constructed as gring@s to uphold the Black-white binary and used as pawns to meet the interests of racist gring@s. Placing Richard Delgado and Juan Perea’s work in conversation with pioneering Chican@ intellectuals Octavio I. Romano-V, Nicolas C. -

Of Minority Youth on Rikers Island Vol

48 Constitutional Rights of Minority Youth on Rikers Island Vol. 6.1 PROTECTING THE CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS OF MINORITY YOUTH ON RIKERS ISLAND LORETTA A. JOHNSON* In 2014, the United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York released a report on their investigation into the patterns and practices of treatment of adolescent inmates on Rikers Island, finding systemic defects that result in the pervasive violation of the adolescent inmates’ constitutional rights. Ninety-five percent of the adolescent population on Rikers is Black or Latino. New York is uniquely harsh with its treatment of 16- and 17-year-olds, as it and North Carolina are the only states to set the minimum age of criminal responsibility at 16. Over seventy-five percent of youth on Rikers Island are awaiting trial and have not been convicted of a crime. The prevalence of the unconstitutional conduct on Rikers Island is attributable, in large part, to the lack of accountability among Department of Corrections (DOC) staff members on Rikers Island, which results in a code of silence. To effectively deal with the pervasive pattern and practice of conduct on the part of DOC staff that violates adolescent inmates on Rikers Island’s constitutional rights, it is crucial to understand the differences between adolescents and adults and the power of the DOC staff union. This Note posits that in order to create meaningful reform and protect the constitutional rights of adolescent inmates, the cut-off age for criminal responsibility should be raised so that 16- and 17-year-olds fall under the jurisdiction of the Family Court and are not placed on Rikers Island. -

Bias and Guilt Before Innocence: How the American Civil Liberties Union Seeks to Reform a System That Penalizes Indigent Defendants

BIAS AND GUILT BEFORE INNOCENCE: HOW THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION SEEKS TO REFORM A SYSTEM THAT PENALIZES INDIGENT DEFENDANTS Candace White * For decades, the United States has debated the concept of a money- bail system, which has been documented to disenfranchise individuals of lower socioeconomic statuses.1 Because the accused’s financial status is often not assessed during bail and arraignment hearings, judges often set bail in excess of the defendant’s financial means.2 As a result, individuals who have not been convicted comprise sixty percent of jail populations,3 and in cases where bail is set moderately low, “at $500 or less, as it is in one-third of nonfelony cases—only 15 percent of defendants are able to come up with the money to avoid jail.”4 In an attempt to rectify discriminatory practices, the United States, under the Obama administration, sought to provide guidance on criminal justice fines and fees,5 however, these instructions were * J.D. Candidate, Albany Law School, 2020; B.S., Stetson University, 2017. I would like to thank Professor Christian Sundquist for his support and guidance in the composition of this Note. I would also like to thank Professors Mary Lynch and Peter Halewood for providing me with endless opportunities to further my legal career and for consistently pushing me to evaluate and critique the American criminal justice system. 1 See Donald B. Verrilli, Jr., The Eighth Amendment and the Right to Bail: Historical Perspectives, 82 COLUM. L. REV. 328, 330 n.13 (1982) (“The federal Bail Reform Act of 1966, 18 U.S.C. -

Crowley Cites Kalief Browder

LOCAL CLASSIFIEDS PAGE 11 April 9, 2017 Your Neighborhood — Your News® Suozzi talk Crowley cites Kalief Browder gets heated at Congressional bill would help former prisoners with mental health problems Jewish Center BY BILL PARRY his new legislation named in his ter the 16-year-old who spent three stealing a backpack. When Kalief honor, which seeks to improve years on Rikers Island, much of it was finally released, he struggled BY MARK HALLUM Clutching a picture of Kalief mental health services for the for- in solitary confinement. with the trauma he endured while Browder on the steps of city hall merly incarcerated. The Bronx teen was frequently in jail, eventually committing sui- Freshman U.S. Rep. Tom Monday, U.S. Rep. Joseph Crowley Crowley’s bill, called the Kalief beaten by guards and inmates and cide in 2015. Suozzi (D-Huntington) reached (D-Jackson Heights) announced Browder Re-Entry Success Act, af- was never formally charged with “Tragically, Kalief’s story is out beyond his district Sunday not uncommon,” Crowley said. for a breakfast Q&A with resi- “The formerly incarcerated often dents at the Hillcrest Jewish struggle to understand and deal Center in Fresh Meadows. with their mental health challeng- Many in attendance, however, READY TO BECOME AN AMERICAN es alongside the myriad of diffi- found his opinions on President culties they face integrating back Donald Trump less than agree- into society. And those who were able. As the talk progressed with treated for existing mental health Suozzi slamming Trump for issues while in prison often face apparent conflicts of interest, discontinuity of treatment and about 10 people stood up and left services once they are no longer out of the crowd of roughly 80. -

Emplacing White Possessive Logics: Socializing Latinx Youth Into Relations with Land, Community, and Success

Emplacing White Possessive Logics: Socializing Latinx Youth into Relations with Land, Community, and Success By Theresa Amalia Stone A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Patricia Baquedano-López, Chair Professor Zeus Leonardo Professor Charles Briggs Summer 2019 Emplacing White Possessive Logics: Socializing Latinx Youth into Relations with Land, Community, and Success @2019 By Theresa Amalia Stone 1 Abstract Emplacing White Possessive Logics: Socializing Latinx Youth into Relations with Land, Community, and Success by Theresa Amalia Stone Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Berkeley Professor Patricia Baquedano-López, Chair This dissertation examines the logics and relations that Latinx youth are socialized into via a college preparation program from a settler colonial studies perspective. An ethnographic project drawing upon critical place inquiry and language socialization approaches, it features data from pláticas and interviews, participant observation, and a multi-sited place project, building upon youths’ and educators’ readings and navigations of their social worlds. It contends that white possessive logics (Moreton- Robinson, 2015) were enacted through a series of classificatory technologies of control which shifted in response to efforts by local educators to employ educational structures and practices that countered them. Further, it examines the navigation of the settler- native-slave triad by Latinx youth, as their status as exogenous others positioned them as not-quite-yet determined within this structure. This dissertation argues that the precarity and tenuousness of life shaped by racialized and gendered vulnerabilities made aspiring towards normative visions of success a (non)option for those given the opportunity to do so. -

The Puzzling Neglect of Hispanic Americans in Research on Police–Citizen Relations Ronald Weitzer Published Online: 08 May 2013

This article was downloaded by: [George Washington University] On: 27 August 2014, At: 14:00 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Ethnic and Racial Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rers20 The puzzling neglect of Hispanic Americans in research on police–citizen relations Ronald Weitzer Published online: 08 May 2013. To cite this article: Ronald Weitzer (2014) The puzzling neglect of Hispanic Americans in research on police–citizen relations, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 37:11, 1995-2013, DOI: 10.1080/01419870.2013.790984 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.790984 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

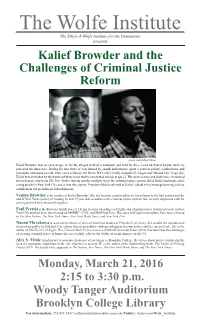

Kalief Browder and the Challenges of Criminal Justice Reform

The Wolfe Institute The Ethyle R.Wolfe Institute for the Humanities, presents Kalief Browder and the Challenges of Criminal Justice Reform photo credit Zach Gross Kalief Browder was arrested at age 16 for the alleged theft of a backpack and held for three years on Rikers Island, while he protested his innocence. During his time there he was abused by guards and inmates, spent 2 years in solitary confinement, and repeatedly attempted suicide. After years of delays, the Bronx DA’s office finally dropped all charges and released him. Tragically, Kalief was so shaken by the trauma of those years that he committed suicide at age 22. His incarceration and death were chronicled in two feature articles in The New Yorker that lay out the multiple ways the criminal justice system failed Kalief and many other young people in New York City and across the country. President Obama referred to Kalief’s death in his message banning solitary confinement for juveniles in federal prisons. Venida Browder is the mother of Kalief Browder. She has become a major advocate for reforms to the bail system and the end of New York’s policy of treating 16 and 17 year olds as adults in the criminal justice system. She recently supported calls for closing down Rikers Island all-together. Paul Prestia is the Browder family lawyer. He has become a leading civil rights and criminal justice reform advocate in New York City and has been interviewed on MSNBC, CNN, and Huff Post Live. His cases and legal commentary have been covered in The New Yorker, The New York Times, New York Daily News, and New York Post. -

Low-Income Black Mothers Parenting Adolescents in the Mass Incarceration Era: the Long Reach of Criminalization

ASRXXX10.1177/0003122419833386American Sociological ReviewElliott and Reid 833386research-article2019 American Sociological Review 2019, Vol. 84(2) 197 –219 Low-Income Black Mothers © American Sociological Association 2019 https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419833386DOI: 10.1177/0003122419833386 Parenting Adolescents in the journals.sagepub.com/home/asr Mass Incarceration Era: The Long Reach of Criminalization Sinikka Elliotta and Megan Reidb Abstract Punitive and disciplinary forms of governance disproportionately target low-income Black Americans for surveillance and punishment, and research finds far-reaching consequences of such criminalization. Drawing on in-depth interviews with 46 low-income Black mothers of adolescents in urban neighborhoods, this article advances understanding of the long reach of criminalization by examining the intersection of two related areas of inquiry: the criminalization of Black youth and the institutional scrutiny and punitive treatment of Black mothers. Findings demonstrate that poor Black mothers calibrate their parenting strategies not only to fears that their children will be criminalized by mainstream institutions and the police, but also to concerns that they themselves will be criminalized as bad mothers who could lose their parenting rights. We develop the concept of “family criminalization” to explain the intertwining of Black mothers’ and children’s vulnerability to institutional surveillance and punishment. We argue that to fully grasp the causes and consequences of mass incarceration and its disproportionate impact on Black youth and adults, sociologists must be attuned to family dynamics and linkages as important to how criminalization unfolds in the lives of Black Americans. Keywords criminalization, mothering, racism, adolescence, mass incarceration Punitive and disciplinary governance struc- Perry 2016; Rios 2011; Shedd 2015; Skiba tures the everyday lives of low-income Black et al. -

Closerikers Campaign: August 2015 – August 2017

Reflections and Lessons from the First Two Phases of the #CLOSErikers Campaign: August 2015 – August 2017 JANUARY 2018 This paper was produced by the Katal Center for Health, Equity, and Justice. The views, conclusions, and recommendations outlined here are those of Katal and do not represent other organizations involved in the #CLOSErikers campaign. No dedicated funding was used to create this paper. For inquiries, please contact gabriel sayegh, Melody Lee, and Lorenzo Jones at [email protected]. © Katal Center for Health, Equity, and Justice 2017. All rights reserved. Katal encourages the dissemination of content from this publication with the condition that reference is made to the source. Suggested Citation Katal Center for Health, Equity, and Justice, Reflections and Lessons from the First Two Phases of the #CLOSErikers Campaign: August 2015–August 2017, (New York: Katal, 2018). Contents Introduction 4 A Brief History of Rikers and Previous Efforts to Shut It Down 6 Political Context and Local Dynamics 8 Movement to End Stop-and-Frisk and Marijuana Arrests 8 Police Killings and #BlackLivesMatter 9 A Scathing Federal Report on Conditions for Youth on Rikers 10 Kalief Browder: Another Rikers Tragedy 11 The National Political Landscape: 2012–2016 11 Media Focus on the Crisis at Rikers 12 A Strategy to #CLOSErikers 13 Campaign Structure and Development 15 Phase One: Building the Campaign and Demand to Close Rikers 15 First Citywide Campaign Meeting 17 Completing Phase One and Preparing for Phase Two 18 First #CLOSErikers Sign-on Letter -

The High Stakes of Low-Level Criminal Justice

ALEXANDRA NATAPOFF The High Stakes of Low-Level Criminal Justice Misdemeanorland: Criminal Courts and Social Control in an Age of Broken Windows Policing BY ISSA KOHLER- HAUSMANN PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2018 abstract. The low-level misdemeanor process is a powerful socio-legal institution that both regulates and generates inequality. At the same time, misdemeanor legal processing often ignores many foundational criminal justice values such as due process, evidence, and even individual guilt. These features are linked: the erosion of the rule of law is one of the concrete mechanisms enabling the misdemeanor system to take aim at the disadvantaged, rather than at the merely guilty. In the book Misdemeanorland, Issa Kohler-Hausmann describes the inegalitarian workings of the misde- meanor legal process in New York City and how it operates as a system of managerial social control over the disadvantaged even when it stops short of convicting and incarcerating them. This Review summarizes the book’s key contributions to the burgeoning scholarly discourse on misdemeanors and then extends its insights about New York to illuminate the broader dynamics and democratic significance of the U.S. misdemeanor process. author. Professor of Law, University of California, Irvine School of Law. Special thanks to Guy-Uriel Charles, Sharon Dolovich, Mona Lynch, and Doug NeJaime. My thanks also to the ed- itors of the Yale Law Journal for their excellent work. 1648 the high stakes of low-level criminal justice book review contents introduction 1650 i. the misdemeanor challenge in national perspective: devaluing due process for the disadvantaged 1659 ii. new york city 1665 A. -

Resources to Continue the Conversation

RESOURCES TO CONTINUE THE CONVERSATION • Be the Bridge https://bethebridge.com • Dallas TRHT (Truth, Racial Healing, Transformation) https://dallastrht.org • National Museum of African American History & Culture: Talking About Race https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race • Talking to Kids About Race https://www.nationalgeographic.com/family/in-the-news/talking-about-race/ • How to Talk to Kids About Race and Racism https://www.parenttoolkit.com/social-and-emotional- development/advice/social-awareness/how-to-talk-to-kids-about-race-and- racism • How White Parents Can Talk To Their Kids About Race o https://www.npr.org/2020/06/03/869071246/how-white-parents-can-talk-to- their-kids-about-race • Teaching Your Child About Black History Month o https://www.pbs.org/parents/thrive/teaching-your-child-about-black-history- month • Your Kids Aren't Too Young to Talk About Race: Resource Roundup from Pretty Good o https://www.prettygooddesign.org/blog/Blog%20Post%20Title%20One-5new4 RESOURCES FOR BECOMING A BETTER ALLY • BOOKS o Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates o White Fragility: Why it’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism, by Robin DiAngelo o White Rage o So You Want to Talk About Race, Ijeoma Oluo o The Person You Mean To Be, by Dolly Chugh o Uprooting Racism, by Paul Kivel o The Souls of Black Folk, by W.E.B. DuBois o The Fire Next Time, by James Baldwin o The Warmth of Other Sons, by Isabel Wilkerson o Race Talk and the Conspiracy of Silence, by Derald Wing Sue o Understanding White Privilege, by Frances Kendall o Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower, by Dr.