Saving Time: Time, Sources, and Implications of Temporality in the Writings of H. P. Blavatsky Submitted by Jeffrey Lavoie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress

THEOSOPHY AND THE ORIGINS OF THE INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS By Mark Bevir Department of Political Science University of California, Berkeley Berkeley CA 94720 USA [E-mail: [email protected]] ABSTRACT A study of the role of theosophy in the formation of the Indian National Congress enhances our understanding of the relationship between neo-Hinduism and political nationalism. Theosophy, and neo-Hinduism more generally, provided western-educated Hindus with a discourse within which to develop their political aspirations in a way that met western notions of legitimacy. It gave them confidence in themselves, experience of organisation, and clear intellectual commitments, and it brought them together with liberal Britons within an all-India framework. It provided the background against which A. O. Hume worked with younger nationalists to found the Congress. KEYWORDS: Blavatsky, Hinduism, A. O. Hume, India, nationalism, theosophy. 2 REFERENCES CITED Archives of the Theosophical Society, Theosophical Society, Adyar, Madras. Banerjea, Surendranath. 1925. A Nation in the Making: Being the Reminiscences of Fifty Years of Public Life . London: H. Milford. Bharati, A. 1970. "The Hindu Renaissance and Its Apologetic Patterns". In Journal of Asian Studies 29: 267-88. Blavatsky, H.P. 1888. The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion and Philosophy . 2 Vols. London: Theosophical Publishing House. ------ 1972. Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology . 2 Vols. Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House. ------ 1977. Collected Writings . 11 Vols. Ed. by Boris de Zirkoff. Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House. Campbell, B. 1980. Ancient Wisdom Revived: A History of the Theosophical Movement . Berkeley: University of California Press. -

TH III-3 July-1990

THEOSOPHICAL July 1990 $3.00 HISTORY A Quarterly Journal of Research ISSN 0951497X Theosophical History A Quarterly Journal of Research Founded by Leslie Price, 1985 Volume 3, No. 3, July 1990 Movement. The Foundation’s Board of Directors consists of the following members: April Hejka-Ekins, Jerry Hejka-Ekins, J. Editor Gordon Melton, and James A. Santucci. James A. Santucci California State University, Fullerton * * * * * Associate Editors The Editors assume no responsibility for the views expressed by John Cooper authors in Theosophical History. University of Sydney The Theosophical History Foundation is a non-profit public bene- Robert Ellwood fit corporation, located at the Department of Religious Studies, University of Southern California California State University, Fullerton, 1800 North State College Boulevard, Fullerton, CA (USA) 92634-9480 (U.S.A.). Its pur- J. Gordon Melton pose is to publish Theosophical History and to facilitate the study Institute for the Study of American Religion, and dissemination of information regarding the Theosophical University of California, Santa Barbara Movement. The Foundation’s Board of Directors consists of the following members: April Hejka-Ekins, Jerry Hejka-Ekins, J. Joscelyn Godwin Gordon Melton, and James A. Santucci. Colgate University * * * * * Gregory Tillett Macquarie University Guidelines for Submission of Manuscripts. The final copy of all manuscripts must be submitted on 8 1/2 x 11 inch paper, dou- THEOSOPHICAL HISTORY (ISSN 0951497X) is published ble-spaced, and with margins of least 1¼ inches on all sides. quarterly in January, April, July and October by the Theosophical Words and phrases intended for italic should be underlined in the History Foundation. The journal’s purpose is to publish contribu- manuscript. -

Harry Collison, MA – Kingston University Working Paper ______

Harry Collison, MA – Kingston University Working Paper __________________________________________________________________________________________ HARRY COLLISON, MA (1868-1945): Soldier, Barrister, Artist, Freemason, Liveryman, Translator and Anthroposophist Sir James Stubbs, when answering a question in 1995 about Harry Collison, whom he had known personally, described him as a dilettante. By this he did not mean someone who took a casual interest in subjects, the modern usage of the term, but someone who enjoys the arts and takes them seriously, its more traditional use. This was certainly true of Collison, who studied art professionally and was an accomplished portraitist and painter of landscapes, but he never had to rely on art for his livelihood. Moreover, he had come to art after periods in the militia and as a barrister and he had once had ambitions of becoming a diplomat. This is his story.1 Collisons in Norfolk, London and South Africa Originally from the area around Tittleshall in Norfolk, where they had evangelical leanings, the Collison family had a pedigree dating back to at least the fourteenth century. They had been merchants in the City of London since the later years of the eighteenth century, latterly as linen drapers. Nicholas Cobb Collison (1758-1841), Harry’s grandfather, appeared as a witness in a case at the Old Bailey in 1800, after the theft of material from his shop at 57 Gracechurch Street. Francis (1795-1876) and John (1790-1863), two of the children of Nicholas and his wife, Elizabeth, née Stoughton (1764-1847), went to the Cape Colony in 1815 and became noted wine producers.2 Francis Collison received the prize for the best brandy at the first Cape of Good Hope Agricultural Society competition in 1833 and, for many years afterwards, Collison was a well- known name in the brandy industry. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

The Vril of Fashion by Siddharta Gargoyle 2 1 2 the Vril of Fashion by Siddharta Gargoyle

The Vril of Fashion by Siddharta Gargoyle 2 1 2 The Vril of Fashion by Siddharta Gargoyle with a foreword by Ralf Wronsov 3 4 thou read’st black where I read white William Blake 5 Previous titles by Ralf Wronsov: Tractatus Fashionablo-Politicus: The Political Philosophy of The Current State of Fashion The Mark of Cain: The Aesthetic Superiority of the Fashionable The Kaiser: A Treatise on Fashion and Power Imprints from The Department of State / No. 4 The Current State of Fashion First Edition October 2015 ISBN: 978-91-980388-2-8 The Current State of Fashion: SelfPassage 6 Foreword 9 The Vril of Fashion 13 The Rune of Janus 19 Chanel: The Avatara of Janus 23 The Name of Violence 27 Christos and Cain: The polarity of principles 31 Vril, the spiritual power of Vogue 35 Runes and Ruins: The Black Sun 39 Wotan’s Warriors of Wogue 43 Appendix: photocopies from Gargoyle’s archive 7 8 Foreword by Ralf Wronsov Fashion! Saturn of Nuit, The unveiling of the raven sky. Only the Beautiful Man and Woman is superior a star. The dark light of the Black Sun: Cain and Chrestos. Let the true violence of Beauty unveil before the Children of men! Siddharta Gargoyle After Hal Vaughan’s influential report on Coco Chanel’s collaboration with the Nazis during the Sec- ond World War, Sleeping with the Enemy, Chanel’s af- fairs with the Germans are well known. Recruited in 1941, she became agent F-7124 of the Abwehr, and later SS. She held the code name Westminster, with the mythical etymology as “ruler of the West”. -

A REFLECTION on the SECRET DOCTRINE, No. 1

January 2012 A REFLECTION ON THE SECRET DOCTRINE , No. 1 The word doctrine may be defined as set of principles or as a body of teachings related to a particular subject. One example from the field of religion would be the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. In the realm of jurisprudence, the doctrine of self-defense is well established. Economists often refer to Marxist or Keynesian doctrines. The military has its doctrines relating to warfare which are studied at West Point and other military academies. A doctrine is something more than a mere idea, or even a concept. For these to be elevated to the status of doctrines, they need to be subjected to a period of intense critical analysis by scholars and experts in that particular field. The principles articulated by Mme. Blavatsky in The Secret Doctrine qualify as doctrines because they are part of a wisdom tradition extending back centuries in time. In his historical introduction to the 1979 edition, Editor Boris de Zirkoff dispenses with the notion that The Secret Doctrine is nothing more than a “syncretistic work wherein a multitude of seemingly unrelated teachings and ideas are cleverly woven together to form a more or less coherent whole” (1:74). It is not difficult to see how a novice reader might arrive at this superficial but erroneous conclusion, given the non-linear style of writing employed by Blavatsky in her magnum opus. To the student possessing a measure of intuitive capacity, deep and sustained consideration will reveal The Secret Doctrine to be “a wholly coherent outline of an ageless doctrine, a system of thought based upon occult facts and universal truths inherent in nature and which are as specific and definite as any mathematical proposition” (1:74). -

The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P

The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett The Early Days of Theosphy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett Theosophical Publishing House Ltd, London, 1922 NOTE [Page 5] Mr. Sinnett's literary Executor in arranging for the publication this volume is prompted to add a few words of explanation. There is naturally some diffidence experienced in placing before the public a posthumous MSS of personal reminiscences dealing in various instances with people still living. It would, however, be impossible to use the editorial blue pencil without destroying the historical value of the MSS. Mr. Sinnett's position and associations with the Theosophical Society together with his standing as an author in the Theosophical movement alike demand that his last writing should be published, and it is left to each reader to form his own judgment as to the value of the book in the light of his own study of the questions involved. Page 1 The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett CHAPTER - 1 - NO record could truly be called a History of the Theosophical Society if it concerned itself merely with events taking shape on the physical plane of life. From the first such events have been the result of activities on a higher plane; of steps taken by the unseen Powers presiding over human evolution, whose existence was unknown in the outer world when their great undertaking — the Theosophical Movement — was originally set on foot. To those known in the outer world as the Founders of the Theosophical Society — Madame Blavatsky and Colonel Olcott — the existence of these higher powers, The Brothers as they were called at first, was more or less imperfectly comprehended. -

Univerzita Karlova Filozofická Fakulta Diplomová

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Ústav filosofie a religionistiky Studijní obor: religionistika DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCE Radical Paganism: Contemporary Heathens in Search of Political Identity Bc. Martina Miechová Vedoucí práce: Tereza Matějčková, Ph.D. 2019 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci vypracovala samostatně, že jsem řádně citovala všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu. V Praze dne 29.7.2019 ........................................ Poděkování Tereza Matějčková, Ph.D. mě podpořila povzbuzujícími konzultacemi, podnětnými připomínkami a trpělivostí během doby, kdy práce vznikala. Jagodě Mackowiak vděčím za přátelskou podporu a Mgr. Veronice Krajíčkové za neocenitelnou radu v začátcích. Nepřímo se o mou práci zasloužil i Adam Anczyk, PhD, který ve mně vzbudil zájem o téma novopohanství a jeho transformace v dnešní společnosti. Všem bych tímto ráda upřímně poděkovala. ABSTRAKT Tato práce si klade za cíl zmapovat vývoj politického myšlení Severského novopohanství a určit faktory, které vedou k politizaci konkrétních typů novopohanských skupin a k jejich příklonu k pravicovému radikalismu. První kapitola po úvodu sestává ze čtyř případových studií, z nichž každá představuje jiný typ skupiny z pohledu místa a okolností vzniku, kontextu, v němž se se vyvíjela jejich náboženská a politická přesvědčení, a ze způsobu legitimizace jejich případného politického aktivismu. Následující dvě kapitoly se soustředí na analýzu historických souvislostí, které zapříčinily rozdílné ideologické směřování skupin v rámci dvou hlavních typů Severského pohanství, Ásatrú a Odinismu, a to ve dvou odlišných kulturních prostředích Evropy a Spojených Států. Závěrečná kapitola přináší syntézu zkoumaných skupin ve vzájemných souvislostech spolu s jejich historickým pozadím; tato syntéza pak nabízí možnou interpretaci procesu jejich radikalizace. -

Theosophy and the Arts

Theosophy and the Arts Ralph Herman Abraham January 17, 2017 Abstract The cosmology of Ancient India, as transcribed by the Theosophists, con- tains innovations that greatly influenced modern Western culture. Here we bring these novel embellishments to the foreground, and explain their influ- ence on the arts. 1. Introduction Following the death of Madame Blavatsky in 1891, Annie Besant ascended to the leadership of the Theosophical Society. The literature of the post-Blavatsky period began with the very influential Thought-Forms by Besant and C. W. Leadbeater, of 1901. The cosmological model of Theosophy is similar to the classical Sanskrit of 6th century BCE. The pancha kosa, in particular, is the model for these authors. The classical pancha kosa (five sheaths or levels) are, from bottom up: physical, vital, mental, intellectual, and bliss. The related idea of the akashic record was promoted by Alfred Sinnett in his book Esoteric Buddhism of 1884. 2. The Esoteric Planes and Bodies The Sanskrit model was adapted and embellished by the early theosophists. 2-1. Sinnett Alfred Percy Sinnett (1840 { 1921) moved to India in 1879, where he was the editor of an English daily. Sinnett returned to England in 1884, where his book, Esoteric 1 Buddhism, was published that year. This was the first text on Theosophy, and was based on his correspondence with masters in India. 2-2. Blavatsky Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831 { 1891) { also known as HPB { was a Russian occultist and world traveller, While reputedly in India in the 1850s, she came under the influence of the ancient teachings of Hindu and Buddhist masters. -

Adventist Heritage, Fall 1985

- • , a.imp.-41M1m-dmin-min• •••=0•••=11.+INIP-maw-4M....Mw-nEw rim cAdventist Fall, 1985 Volume 10 Number 2 ISSN 0360-389X A JOURNAL OF ADVENTIST HISTORY MANAGING EDITOR Paul J. Lands Loma Linda University EDITORS Editor's Stump Dorothy Minchin-Comm Loma Linda Univemity Dorothy Minchin-Comm 2 Gary Land Andrews University A TIME OF BEGINNINGS ASSISTANT EDITORS Noel P. Clapham Ronald Grayhill 3 Columbia Union James It Nix 4 THIEVES AMONG THE MERINOS? Loan Linda University Tales from the Gospel Trail ASSISTANT TO THE MANAGING Elaine J. Fletcher 7 EDITOR Mary E. Khalaf Loma Linda University FULFILLING THE GOLDEN DREAM: The Growth of Adventism in New Zealand LAYOUT AND DESIGN EDITORS Ross Goldstone Mary E. Khalaf 19 Lorna Linda. University Judy Uu-son THE WAY OF THE WORD: Lake Elsitu.Pre, Ca. The Story of the Publishing Work in Australia PHOTOGRAPIIY Donald E. Hansen 26 Carol Fisk Lonna hinda University KWIC-BRU, GRANOSE, GRANOLA AND THE GOSPEL TYPESETTING Robert H. Parr 36 Mary E. Khalaf Lama Linda University HEIRLOOM The Family in the Shop MANAGING BOARD Dorothy Minchin-Comm 46 Helen Ward Thompson, Chairman Frederick G. Hoyt, Seeretniv James Greene SONGS OF THE ISLANDS: Maurice Hodgen Adventist Missions in the South Pacific Paul I Landa Judy Larson Robert D. Dixon and Dorothy Minchin-Comm 50 Dorothy Minchin-Comm Kenneth L. Vine BOOKMARK: A Fourth Book of Chronicles: Norman J. Woods A Review or Arthur L. White, Ellen G. White: The Australian Years, EDITORIAL BOARD 1891-1900. Frederick G. Hoyt, Choir-man Arthur N. Patrick Paul Lands, Sec-retail/ 62 Gary Land Judy Larson Dorothy Mine/lin-Comm Mary E. -

Introduction to the Mahatma Letters - V

An Overview of The Mahatma Letters Mahatma Letters Mahatma The Mahatma Letters Letters Reference Books Books on Mahatma Letters Mahatma Letters The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett - A.T. Barker The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett in chronological sequence arranged and edited by Vicente Hao Chin, Jr. Readers’ Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett - George E. Linton & Virginia Hanson The Mahatmas And Their Letters - Geoffrey Barborka An Introduction to The Mahatma Letters - V. Hanson Masters and Men - Virginia Hanson The Occult World - A. P. Sinnett The Story of The Mahatma Letters – C. Jinarajadasa More Books on Mahatma Letters Mahatma The Early Teachings of the Masters - C. Jinarajadasa Letters Letters From The Masters Of The Wisdom, First & Second Series - C. Jinarajadasa The “K. H.” Letters to C. W. Leadbeater – C. Jinarajadasa Esoteric Buddhism - A. P. Sinnett Letters of H. P. Blavatsky to A. P. Sinnett - A. T. Barker A Short History of the Theosophical Society - Josephine Ransom The Golden Book of the Theosophical Society - C. Jinarajadasa Damodar and the Pioneers of the Theosophical Movement - Sven Eek Autobiography of Alfred Percy Sinnett - A. P. Sinnett Reflections on an Ageless Wisdom – Joy Mills Mrs. Holloway and the Mahatmas – Daniel Caldwell Mahatma Letters The Mahatmas The Mahatmas Mahatma Letters High Initiates and Members of the Occult Hierarchy Directed the founding of the Theosophical Society in 1875 Two of Them are especially concerned with The Theosophical Society A number of Adepts communicated with and guided the founders and members in the early days Much of the esoteric writings of H. -

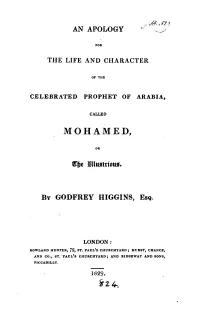

Apology for the Life and Character of Mohamed

,. ,Wx "' AN APOLOGY ~__,» THE LIFE AND CHARACTER CELEBRATED PROPHET OF ARABLM CALLED _MOHAMER I OR 'EITD8 iElllt5trf0tt§. BY GODFREY HIGGINS, ESQ. LONDON: now1.ANn uvrlnn, 72, sr. nur/s cuuncmumu; uu|v.s'r, CHANCE .mn co sr l'AUL'S cnuncmmnn; AND RIDGLWAY AND sons |>|ccA|m.|.Y 1829. 5:2/,__ » 5 )' -? -X ~.» Kit;"L-» wil XA » F '<§i3*". *> F Q' HIi PRINTED DY G. SMALLFIELIJ, HACKNEY T0 THE NOBLEMEN AND GENTLEMEN OF THE ASIATIC SO- CIETY OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND. To you, my Lords and Gentlemen, I take the liberty of dedicating this small Tract, because I am desirous of correcting what appear to me to be the erroneous opinions which some of the individuals of your Society (as well as others of my countrymen) entertain respecting the religion of many millions of the inhabitants of the Oriental Countries, about the welfare of whom you meritoriously interest your- selves; and, because a right understanding of their religion, by you, is of the first importance to their welfare. I do it without the knowledge or approba- tion of the Society, or of any of its Members, in order that they may not be implicated in my senti- ments. , » With the most sincere wishes for the welfare ot the Society, and with great respect, I remain, my Lords and Gentlemen, Your most obedient, humble servant, GODFREY HIGGINS, M. ASIAT. soc. ~ Sxznnow Gamez, NEAR Doucasrnu, July, lB29. ERRATUM. Page 80, line l§, for the " Aleph," read a Daleth, and for " H. M. A.," read IL M. D. PREFACE.