American Promotional Road Mapping in the Twentieth Century James R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GREENING ROME the Urban Green of the Metropolitan Area of Rome in the Context of the Italian MAES Process

GREENING ROME The Urban Green of the Metropolitan Area of Rome in the Context of the Italian MAES Process Italian Ministry for the Environment and the Protection of Land and Sea - Maria Carmela Giarratano - Eleonora Bianchi - Eugenio Dupré Italian Botanical Society - Scientific Coordination: Carlo Blasi - Working Group: Marta Alós, Fabio Attorre, Mattia Martin Azzella, Giulia Capotorti, Riccardo Copiz, Lina Fusaro, Fausto Manes, Federica Marando, Marco Marchetti, Barbara Mollo, Elisabetta Salvatori, Laura Zavattero, Pier Carlo Zingari 1. Introduction The Italian Ministry for the Environment provides financial support to academia (Italian Botanical Society – SBI and Italian Zoological Union – UZI) for the implementation of the MAES process in Italy. A preliminary collection of updated and detailed basic data at the national level was carried out, including ecoregions, land units, bioclimate, biogeography, potential natural vegetation and CORINE land cover at the fourth level. Starting from these data, the Italian MAES process has been organised into six steps. The outcomes of this process have provided the Ministry for the Environment with a reliable body of information targeted to: - an effective implementation of the National Biodiversity Strategy (MATTM 2010); - the improvement in biodiversity data within the National Biodiversity Network (Martellos et al. 2011); - the further development of the environmental accounting system (Capotorti et al. 2012b); - the implementation of a road-map to be delivered to the regions (sub-national level); - the effective use of the products of all MAES process to concretely support European structural and investment funds 2014-2020 through the Joint Committee on Biodiversity, the governing body of the Italian National Strategy (Capotorti et al., 2015). -

Michelin Italy: Central Map 563 Ebook

MICHELIN ITALY: CENTRAL MAP 563 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michelin Travel & Lifestyle | 1 pages | 16 Apr 2012 | Michelin Editions Des Voyages | 9782067175341 | English | Paris, France Michelin Italy: Central Map 563 PDF Book I know my way around most of Tuscany but I find that the best route is the one you get by following signs. Political, administrative, road, physical, topographical, travel and other map of Italy. Road Maps Of Sicily. Michael, We have been to Tuscany many times and I found a map that works great for us. Because Venice is built with small narrow streets which cannot provide you with an angle to see entire buildings, there are views from the Vaporetto that beats anything you can see on land. It's this kind of detail that can, for example, help North American tourists avoid surprises while traveling down narrow roads that are often hundreds of years old. Political map of Italy with roads and cities. It is just for Tuscany and is very detailed. In-house cartographers, or mapmakers, produce each map and atlas and leave no stone unturned. Check out our car rental service and all its many benefits:. Turning back to Rick's book, intros to each chapter will often mention places to park. Renting a car, an attractive proposition for the holidays Renting a car Renting a car can be financially advantageous. They exist "online" but are too small and incomplete to be of much help. Several possible answers. You can buy one at any newsstand. You can also transfer your calculated routes from your computer to the app: to do this, you must save it in your Favourites via your Michelin account. -

A Road Map for Global Action on Methane

North American Climate Leadership A road map for global action on methane In April, world leaders from 175 countries gathered to sign the landmark global climate agreement reached in Paris in December 2015. Now attention turns to what actions each country will take to achieve these goals and, in particular, what can be done immediately to change the perilous path we are on and rein in the record rate of warming that our planet is experiencing now. Research is also bringing into focus the difference between various greenhouse gases and the importance of reducing both powerful, long‑lived climate pollutants like carbon dioxide (CO2), along with potent, Failing to take short‑lived pollutants such as methane (CH ).1 Both require attention “ 4 action on methane as long‑lived climate pollutants dictate how warm the planet gets, while would be a major short‑lived climate pollutants determine how fast the warming happens. missed opportunity According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), reducing methane to tackle near-term from the oil and gas sector—the largest emitting industry—is one of five key opportunities for achieving meaningful cuts in greenhouse gases.2 It warming as the can be done affordably, with existing technology and with minimal impact necessary longer- on industry.3 As such, reducing oil and gas methane is one of the most term reductions effective tools we have to curb current warming while we simultaneously in carbon dioxide work to slow future warming vis‑à‑vis carbon dioxide reductions. The United States, Canada and Mexico are three of the world’s largest are implemented. -

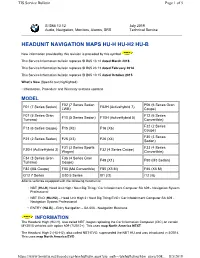

Headunit Navigation Maps Hu-H Hu-H2 Hu-B

TIS Service Bulletin Page 1 of 5 SI B65 13 12 July 2019 Audio, Navigation, Monitors, Alarms, SRS Technical Service HEADUNIT NAVIGATION MAPS HU-H HU-H2 HU-B New information provided by this revision is preceded by this symbol . This Service Information bulletin replaces SI B65 13 12 dated March 2018 This Service Information bulletin replaces SI B65 23 13 dated February 2014 This Service Information bulletin replaces SI B65 10 15 dated October 2015 What’s New (Specific text highlighted): • Information, Procedure and Warranty sections updated MODEL F02 (7 Series Sedan F06 (6 Series Gran F01 (7 Series Sedan) F02H (Activehybrid 7) LWB) Coupe) F07 (5 Series Gran F12 (6 Series F10 (5 Series Sedan) F10H (ActiveHybrid 5) Turismo) Convertible) F22 (2 Series F13 (6 Series Coupe) F15 (X5) F16 (X6) Coupe) F30 (3 Series F23 (2 Series Sedan) F25 (X3) F26 (X4) Sedan) F31 (3 Series Sports F33 (4 Series F30H (ActiveHybrid 3) F32 (4 Series Coupe) Wagon) Convertible) F34 (3 Series Gran F36 (4 Series Gran F48 (X1) F80 (M3 Sedan) Turismo) Coupe) F82 (M4 Coupe) F83 (M4 Convertible) F85 (X5 M) F86 (X6 M) G12 7 Series G30 5 Series I01 (i3) I12 (i8) Affects vehicles equipped with the following head units: •NBT (HU-H) Head Unit High / Next Big Thing / Car Infotainment Computer SA 609 - Navigation System Professional • NBT EVO (HU-H2) – Head Unit High 2 / Next Big Thing EVO / Car Infotainment Computer SA 609 - Navigation System Professional • ENTRY (HU-B) – Entry Navigation – SA 606 - Navigation Business INFORMATION The Headunit High (HU-H), also called NBT, began replacing the Car Information Computer (CIC) on certain MY2013 vehicles with option 609 (7/2012+). -

What Is UNEP/MAP – Barcelona Convention?

UNEP/MAP and Environmental Challenges in the Mediterranean by Atila URAS, Programme Officer UNEP/MAP Barcelona Convention 1 October, 2012, Venice What is UNEP/MAP – Barcelona Convention? • An institutional cooperation framework gathering the 21 countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea, and the European Union; • Goal: to protect the marine and coastal environment of the Mediterranean Sea; • First UNEP Regional Seas Programme; • A resilient cooperation tool among Mediterranean countries; • A catalyser of action by those who conduct has an impact on the Mediterranean environment. UNEP/MAP added value • Regional environmental legal framework • political decision-making body • communication and coordination network • periodic assessment of the status and threats • Integrated strategy of protection and sustainable development measures • network of technical centres and programmes Barcelona Convention and its Protocols Creating synergies for the Mediterranean environment UNEP/MAP Cooperation and Synergies MAP Components: • Strong Partnership MAP/Horizon 2020; EU • Coordinating Unit • MEDPOL • MAP/GEF Strategic Partnership for Large Marine Ecosystem • Plan Bleu • PAP/RAC • World Bank-GEF Sustainable Development Initiative • SPA/RAC • REMPEC • Cooperation with EEA • INFO/RAC • CP/RAC • Assessment of MAP-NGOs cooperation through a • 100 Historic Sites Programme participatory approach • Financial assistance for activities to MAP partners Integrate the environment into sectorial approaches Mediterranean Strategy for Sustainable Development: • framework -

European “Road Map for Action”

The Societal Impact of Pain – A Road Map for Action European Road Map Monitor 2011 Pilot Project - Preliminary Results Publisher: E. Alon, H.G. Kress, R. Langford, N. Krcevski Skvarc, R.-D. Treede, G. Varrassi, K. C. P. Vissers, J. C. D. Wells Authors: Rolf-Detlef Treede, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg Univesity, Germany Norbert van Rooij, Governmental Affairs & Health Policy, Grünenthal GmbH The scientific framework of the SIP platform is under the responsibility of the European Federation of IASP® Chapters (EFIC®). The pharmaceutical company SIP Grünenthal GmbH is responsible for funding and non- Societal Impact of Pain financial support (e.g. logistical support). The Societal Impact of Pain – A Road Map for Action EFIC® (European Federation of IASP® Chapters) European Road Map Monitor 2011 Medialaan 24 1800 Vilvoorde Belgium [email protected] Pilot Project - Preliminary Results http://www.efic.org EU Transparency Register ID: 35010244568-04 Publisher: This booklet supports the Societal Impact of Pain – European Road E. Alon, H.G. Kress, R. Langford, N. Krcevski Skvarc, Map Monitor 2011. You can copy, download or print the contents R.-D. Treede, G. Varrassi, K. C. P. Vissers, J. C. D. Wells of this booklet for your own use provided suitable acknowledgment of EFIC® and the EU Liaison Committee is given. The authors and the Authors: publisher as source and copyright owner should also be given. All Rolf-Detlef Treede, Medical Faculty Mannheim, requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should Heidelberg Univesity, Germany be submitted to [email protected]. Norbert van Rooij, Governmental Affairs & Health Policy, The scientific framework of this publication is under the Grünenthal GmbH responsibility of the European Federation of IASP® Chapters (EFIC®). -

Openstreetmap History for Intrinsic Quality Assessment: Is OSM Up-To-Date? Marco Minghini1,3* and Francesco Frassinelli2,3

Minghini and Frassinelli Open Geospatial Data, Software and Standards (2019) 4:9 Open Geospatial Data, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40965-019-0067-x Software and Standards SOFTWARE Open Access OpenStreetMap history for intrinsic quality assessment: Is OSM up-to-date? Marco Minghini1,3* and Francesco Frassinelli2,3 Abstract OpenStreetMap (OSM) is a well-known crowdsourcing project which aims to create a geospatial database of the whole world. Intrinsic approaches based on the analysis of the history of data, i.e. its evolution over time, have become an established way to assess OSM quality. After a comprehensive review of scientific as well as software applications focused on the visualization, analysis and processing of OSM history, the paper presents “Is OSM up-to-date?”, an open source web application addressing the need of OSM contributors, community leaders and researchers to quickly assess OSM intrinsic quality based on the object history for any specific region. The software, mainly written in Python, can be also run in the command line or inside a Docker container. The technical architecture, sample applications and future developments of the software are also presented in the paper. Keywords: Crowdsourcing, Data history, Data quality, Open source, OpenStreetMap, up-to-dateness Introduction of software tools, services and applications allows a wide OpenStreetMap (OSM) is the most successful crowd- number of developers, humanitarian operators, industry sourced geographic information project to date [1]. It was and governmental actors to exploit OSM data on a daily initiated in 2004 in response to the mainstream pres- basis and for a variety of purposes [6]. -

Mapping Rural Road Networks from Global Positioning System (GPS) Trajectories of Motorcycle Taxis in Sigomre Area, Siaya County, Kenya

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Mapping Rural Road Networks from Global Positioning System (GPS) Trajectories of Motorcycle Taxis in Sigomre Area, Siaya County, Kenya Francis Oloo ID Department of Geoinformatics, University of Salzburg, Schillerstrasse, 30-5020 Salzburg, Austria; [email protected]; Tel.: +43-662-8044-7569 Received: 25 June 2018; Accepted: 30 July 2018; Published: 1 August 2018 Abstract: Effective transport infrastructure is an essential component of economic integration, accessibility to vital social services and a means of mitigation in times of emergency. Rural areas in Africa are largely characterized by poor transport infrastructure. This poor state of rural road networks contributes to the vulnerability of communities in developing countries by hampering access to vital social services and opportunities. In addition, maps of road networks are incomplete, and not up-to-date. Lack of accurate maps of village-level road networks hinders determination of access to social services and timely response to emergencies in remote locations. In some countries in sub-Saharan Africa, communities in rural areas and some in urban areas have devised an alternative mode of public transport system that is reliant on motorcycle taxis. This new mode of transport has improved local mobility and has created a vibrant economy that depends on the motorcycle taxi business. The taxi system also offers an opportunity for understanding local-level mobility and the characterization of the underlying transport infrastructure. By capturing the spatial and temporal characteristics of the taxis, we could design detailed maps of rural infrastructure and reveal the human mobility patterns that are associated with the motorcycle taxi system. -

PLM ROAD MAP North America 2018 15-17 May Washington D.C. Metro

CIMdata eBook PLM ROAD MAP North America 2018 in collaboration with PDT North America 2018 15-17 May Washington D.C. metro area, USA Short eBrochure Global Leaders in PLM Consulting www.CIMdata.com Welcome JOIN PLM ROAD MAP & PDT IN THE WASHINGTON D.C. AREA Themes About JOIN PLM ROAD MAP & PDT IN THE METRO WASHINGTON D.C. AREA Agenda We are delighted to invite you to be part of PLM Road Map™ NA 2018 and PDT NA Why Attend? 2018 by joining us in the Dulles Technology Corridor, near Washington D.C. for what promises to be the most important PLM event of the year. Venue Agendas are being developed and curated with the primary aim of delivering high value to the wider PLM economy. Cost PLM Road Map NA 2018, in collaboration with PDT NA 2018, is the must-attend event for PLM practitioners globally—providing independent education and a Testimonials collaborative networking environment where ideas, trends, experiences, and relationships critical to the PLM industry germinate and take root. To learn more contact: CIMdata @ [email protected] * For translations into languages using non-Roman alphabets, other fonts may be appropriate. 2 Welcome CONFERENCE THEMES Themes About Our conference themes for 2018 reflect the future Agenda state of PLM Why Attend? The theme for PLM Road Map NA 2018 is: Venue Charting the Course to PLM Value Together: Expanding the Value Footprint of PLM & Tackling PLM’s Persistent Pain Cost Points The theme for PDT NA 2018 is: Testimonials Collaboration in the Engineering Supply Chain: The Extended Digital Thread * For translations into languages using non-Roman alphabets, other fonts may be appropriate. -

Road Map for Accession and Implementation UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION for EUROPE

UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE ADR Road map for accession and implementation UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE European Agreement Concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road (ADR) Road map for accession and implementation Note The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ECE/TRANS/0238 Copyright © United Nations, 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may, for sales purposes, be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the United Nations. United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) is one of the five United Nations regional commissions, administered by the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). It was established in 1947 with the mandate to help rebuild post-war Europe, develop economic activity and strengthen economic relations among European countries, and between Europe and the rest of the world. During the Cold War, UNECE served as a unique forum for economic dialogue and cooperation between East and West. Despite the complexity of this period, significant achievements were made, with consensus reached on numerous harmonization and standardization agreements. In the post-Cold War era, UNECE acquired not only many new member States, but also new functions. -

Matching Gift Programs

Plexus Technology Group,$50 SPX Corp,d,$100 TPG Capital,$100 U.S. Venture,$25 Maximize the Impact of Your Gift Plum Creek Timber Co Inc.,$25 SPX FLOW,d,$100 TSI Solutions,$25 U.S.A. Motor Lines,$1 Pohlad Family Fdn,$25 SSL Space Systems/Loral,$100 Tableau Software,$25 UBM Point72 Asset Mgt, L.P. STARR Companies,$100 Taconic Fdn, Inc.,$25 UBS Investment Bank/Global Asset Mgt,$50 Polk Brothers Fdn Sabre Holdings Campaign (October 2017),$1 Taft Communications,$1 Umpqua Bank,$1 Polycom Inc.,$20 Safety INS Group, Inc.,$250 Takeda Pharma NA,$25 Unilever North America (HQ),s,d Portfolio Recovery Associates,$25 Sage Publications, Inc.,$25 Talent Music,$5 Union Pacific Corp MoneyPLUS,d Match Your Gift PotashCorp,d,$25 Salesforce.com,$50 Tallan Union Pacific Corp TimePLUS,$25 Potenza,$50 Sallie Mae Dollars for Doers,d Talyst,$25 United States Cellular Corp,$25 when you donate to Power Integrations,$25 Saltchuk,$25 Tampa Bay Times Fund,r,$25 United Technologies Corp - UTC,d,$25 Praxair,d,$25 Samaxx,$5 TargetCW,$1 UnitedHealth Group Precor,$25 Samuel Roberts Noble Fdn Inc.,d,$100 Teagle Fdn, Inc.,d UnitedHealth Group (Volunteer) Preferred Personnel Solutions SanMar Technology Sciences Group,$10 Universal Leaf Tobacco Corp,$25 Preformed Line Products Co,r,d,$25 Sandmeyer Steel Co,r,$50 Teichert, Inc. Unum Corp,2:1,d,$50 Premier, Inc.,$50 Sanofi,$50 Teknicks,$1 Premier, Inc. Volunteer,$25 Schneider Electric Co (Cash & Volunteer),d,$25 Tektronix, Inc.,d,$20 Principal Financial Group,r,$50 Scripps Networks Interactive,r,$25 Teleflex,r,d,$50 V/W/X/Y/Z VISA Intl ProLogis,d,$50 Scripps Networks Volunteer,d,$250 Teradata Campaign (October),$25 VMware Inc.,$31 ProQuest LLC,$25 Securian Financial Group,r,d,$35 Terex Corp,$50 Vanderbilt Ventures, Inc. -

Los Angeles Promotional Literature, 1885-1915

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE THE SELLING OF A MYTH: 1\ LOS ANGELES PROMOTIONAL LITERATURE, 1885-1915 A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Mass Communication by Judith Wilnin Elias August, 1979 The Thesis of Judith Wilnin Elias is approved: - California State University, Northridge ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT Special thanks to Susan Henry, for her encouragement and expertise Sam Feldman, for his understanding and enthusiasm John Baur, for his experience and knowledge and sincere appreciation to Carey McWilliams, for his support of an unconventional idea. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT . v Chapter I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE . • . • • . 9 III. METHODOLOGY ....... 24 IV. THE LEGEND OF LOS ANGELES: The Climate and the Dream . 32 V. THE SELLING OF LOS ANGELES: The Chamber, the Colonel and the Railroads. • . 47 VI. THE HARVESTING OF LOS ANGELES: Oil and Oranges . 73 VII. THE FOLKLORE OF LOS ANGELES: The Electric Theatre ... : . 86 VIII. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS . 97 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY . 109 APPENDIX A . 122 APPENDIX B . 123 ! • iv ABSTRACT THE SELLING OF A MYTH: LOS ANGELES PROMOTIONAL LITERATURE~ 1885-1915 by Judith Wilnin Elias Master of Arts in Mass Communication At the end of the 19th century, Los Angeles created a legend of a mythical city through the continual use of self-advertising and promotion. This publicity, which included descriptive accounts, rail road propaganda, newspaper and magazine material and advertisements! was largely responsible for the city's phenomenal growth. This thesis is a study of the promotional practices used during Los Angeles' formative years, and deals with the psychological and sociological aspects of the booster literature of that era; The self-interests of the railroads, the real estate specula tors, the oil, citrus, manufacturing and other enthusiasts provided the impetus for what became the most intensive public relations effort the country had yet experienced, and which produced unprecedented results.