CH2(1).131-136.Buchan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Greek Syllabus Greek

ANN ROINN OIDEACHAIS THE JUNIOR CERTIFICATE ANCIENT GREEK SYLLABUS GREEK 1. RATIONALE 1.1 Greek, of which the modern Greek language is its latest development, belongs to the family of Indo-European languages. With the decipherment of the linear B tablets, the written record of the Greek language now extends back to at least 1200 B.C. 1.2 The ancient Greeks were the first European people to record comprehensively -consciously and unconsciously - their intellectual development in the historical, psychological, political, philosophical, literary, artistic and mathematical domains. Consequently the roots of most major intellectual pursuits today derive ultimately from a Greek foundation. In the political field, for example, we owe to the Greeks our notions of monarchy, oligarchy and democracy. Indeed the words we use to indicate such political situations are themselves Greek, as is the fundamental term 'politician'. Likewise, the need we feel to investigate and record impartially contemporary events for future generations (essentially current affairs and history) was a Greek preoccupation. (The Greek word historia means both 'the activity of learning by inquiry' and 'the retelling of what one has learnt by inquiry', which is what the great Greek historians and philosophers tried to do.) 1.3 The Greeks recorded this intellectual development not only with the brilliant clarity of pioneers but with a sublimity which transcends its era and guarantees its timelessness. 1.4 The particular educational importance of Greek rests on the following general -

Classics in Greece J-Term Flyer

WANG CENTER WANG Ancient Greece is often held in reverential awe, and Excursions around Greece to places including: praised for its iconic values, contributions, • Epidaurus: a famous center of healing in antiquity and site and innovations. However, much of what has been of one of the best preserved Greek theaters in the world considered iconic is, in fact, the product of a • Piraeus, Cape Sounion, and the Battle site of Marathon western classical tradition that re-imagines and re- • Eleusis, Corinth, Acrocorinth, and Corinth Canal fashions its ancient past to meet its present • Nauplion, a charming seaside city and the first capital of AWAY STUDY J-TERM needs. In this course, you will explore the romance modern Greece – and the realities – of ancient Greece in Greece. • Mycene and Tiryns, the legendary homes of Agamemnon and the hero Herakles Explore Athens, the birthplace of democracy, and • Ancient Olympia: where the original Olympics were the ruins of Mycenae, from which the Trojan War celebrated. was launched. Examine the evidence for yourself • The mountain monastery, and UNESCO World Heritage in Greece’s many museums and archeological site, of Hosios Loukas. sites. Learn how the western classical heritage has • Delphi: the oracle of the ancient world. reinvented itself over time, and re-envision what • Daytrip to Hydra island (optional). this tradition may yet have to say that is relevant, fresh, and contemporary. Highlights include exploring Athens, its environments, and the Peloponnesus with expert faculty. Scheduled site visits include: • Acropolis and Parthenon • Pnyx, Athenian Agora, and Library of Hadrian • Temples of Olympian Zeus, Hephaistus, and Asclepius • Theaters of Dionysus and Odeon of Herodes Atticus • Plaka and Monastiraki flea market • Lycebettus Hill, and the neighborhoods of Athens • National Archeological, New Acropolis, and Benaki museums “Eternal Summer Gilds Them Yet”: The Literature, Legend, and Legacy of Ancient Greece GREECE Educating to achieve a just, healthy, sustainable and peaceful world, both locally and globally. -

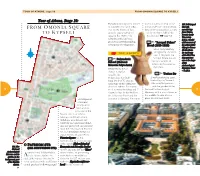

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

Athens Strikes & Protests Survival Guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the Crisis Day Trip Delphi, the Navel of the World Ski Around Athens Yes You Can!

Hotels Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Events Maps ATHENS Strikes & Protests Survival guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the crisis Day trip Delphi, the Navel of the world Ski around Athens Yes you can! N°21 - €2 inyourpocket.com CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES Contents The Basics Facts, habits, attitudes 6 History A few thousand years in two pages 10 Districts of Athens Be seen in the right places 12 Budget Athens What crisis? 14 Strikes & Protests A survival guide 15 Day trip Antique shop Spend a day at the Navel of the world 16 Dining & Nightlife Ski time Restaurants Best resorts around Athens 17 How to avoid eating like a ‘tourist’ 23 Cafés Where to stay Join the ‘frappé’ nation 28 5* or hostels, the best is here for you 18 Nightlife One of the main reasons you’re here! 30 Gay Athens 34 Sightseeing Monuments and Archaeological Sites 36 Acropolis Museum 40 Museums 42 Historic Buildings 46 Getting Around Airplanes, boats and trains 49 Shopping 53 Directory 56 Maps & Index Metro map 59 City map 60 Index 66 A pleasant but rare Athenian view athens.inyourpocket.com Winter 2011 - 2012 4 FOREWORD ARRIVING IN ATHENS he financial avalanche that started two years ago Tfrom Greece and has now spread all over Europe, Europe In Your Pocket has left the country and its citizens on their knees. The population has already gone through the stages of denial and anger and is slowly coming to terms with the idea that their life is never going to be the same again. -

Conference Guide

Conference Guide Conference Venue Conference Location: Radisson Blu Athens Park Hotel 5* 5Hotel Athens” Radisson Blu Park Hotel Athens first opened its doors in 1976 on the border of the central park of Athens, Pedion Areos (Martian Field), in a safe part of the city. For 35 years the lovely park has been a wonderful host and marked the very identity of this leading deluxe hotel. Now, we thought, it is time for the hotel to host the park inside. This was the inspiration behind our recent renovation, which came to prove a virtual rebirth for Park Hotel Athens. Address: 10 Alexandras Ave. -10682 Athens-Greece Tel: +30 210 8894500 Fax: +30 210 8238420 URL: http://www.rbathenspark.com/index.php History of Athens According to tradition, Athens was governed until c.1000 B.C. by Ionian kings, who had gained suzerainty over all Attica. After the Ionian kings Athens was rigidly governed by its aristocrats through the archontate until Solon began to enact liberal reforms in 594 B.C. Solon abolished serfdom, modified the harsh laws attributed to Draco (who had governed Athens c.621 B.C.), and altered the economy and constitution to give power to all the propertied classes, thus establishing a limited democracy. His economic reforms were largely retained when Athens came under (560–511 B.C.) the rule of the tyrant Pisistratus and his sons Hippias and Hipparchus. During this period the city's economy boomed and its culture flourished. Building on the system of Solon, Cleisthenes then established a democracy for the freemen of Athens, and the city remained a democracy during most of the years of its greatness. -

Travel Dates

GROUP TRAVELING: TRAVEL DATES: DAY 1 – TRAVEL DAY DAY 2 – PARLIAMENT SQUARE / NATIONAL ARCHEOLOGICAL MUSEUM / MT. LYCABETTUS • After meeting your JE Guide at the airport, you will transfer by coach to your hotel. • Parliament Building & Changing of the Guard • National Archeological Museum • Dinner Tonight your group may opt for an evening stroll up Mount Lycabettus for a great view of Athens! DAY 3 – AREOPAGUS HILL / ANCIENT AGORA / ACROPOLIS / LOCAL MARKET • Breakfast • Areopagus Hill (Mars Hill) • Ancient Agora • Lunch • Acropolis: Temple of Athena, Parthenon, Theatre of Dionysus, and Odeon of Herodes Atticus • Shopping at the Monastiraki Flea Market or The Central Market • Dinner * Tonight your group may opt to return to the Agora area for a night view of the Acropolis! DAY 4 – ATTEND A LOCAL CHURCH / PLAKA DISTRICT / TEMPLE OF OLYMPIAN ZEUS AREA • Breakfast • Attend a local church • Lunch • Arch of Hadrian, the ruins of the Temple of Olympian Zeus, and the site of the first modern Olympic Games. • Panathenaic Stadium • Shopping in the Plaka district Joshua Expeditions | (888) 341-7888 | joshuaexpeditions.org ©Joshua Expeditions. All rights reserved. GROUP TRAVELING: TRAVEL DATES: • Dinner* * Tonight your group may opt to attend a traditional dance or theater performance – ask for prices! DAY 5 – DAY TRIP (Select when requesting quote) • OPTION 1: • Ancient Corinth & Loutra Oraias Elenis (A beach, named after its most famous visitor, Helen of Troy!) • OPTION 2: • Greek Island Day Cruise DAY 6: TRAVEL DAY STAY LONGER? • Add 2-3 days, and visit the famous Meteora Monastery region, Thessaloniki, or do a Greek Islands Cruise! Interested in this trip experience? Contact our Travel Specialist today! (888) 341-7888 | joshuaexpeditions.org Joshua Expeditions | (888) 341-7888 | joshuaexpeditions.org ©Joshua Expeditions. -

Athens and the Greek Isles

GlobetrottersGASTON A Publication of Gaston College Study Tours Spring 2018 Athens and the Greek Isles The roots of modern Western Civilization lie on the hundreds of rocky islands that dot the Aegean Sea and on the rugged, Inside… mountainous mainland of Hellas (Greece). The earliest civilization that we call “Greek” began on the Island of Crete Athens & the Greek Isles 1 in the midst of the wine-dark Mediterranean Sea around 2500 BCE. People from Egypt, the Middle East, and to the west Itinerary Overview 2 settled on this rocky island and began a brilliant “Minoan” Tour Details 2-4 civilization that would span about 1,000 years. From the early Greeks we inherited such important things as a belief in Tour Package 5 democracy, equality under the law, and even trial by jury. The Reservations 6 Greeks are also responsible for introducing many literary forms and were pioneers in many fields such as physics, philosophy, logic, history, geometry, the theater, and biology. Created & Edited by Bob Blanton Design & Layout by Debbie Bowen (continued on page 2) www.gaston.edu Itinerary Athens and the Greek Isles May 14-23, 2018 Overview Join us in May, 2018, for an exciting 10-day tour of the Greek capital Day 1 - city Athens and three of the most beautiful Greek Isles: Mykonos, Monday, May 14 Crete, and Santorini. We will have the opportunity to sample Flight to Athens traditional Greek food and beverages, enjoy Greek music and folk dancing, and travel across the spectacular Aegean Sea from one Day 2 - island to another on our itinerary. -

Motorcycle Tour Greece, Best of Greece on a BMW Motorcycle Tour Greece, Best of Greece on a BMW

Motorcycle tour Greece, Best of Greece on a BMW Motorcycle tour Greece, Best of Greece on a BMW durada dificultat Vehicle de suport 11 días alt Si Language guia en,es Si Enjoy your Greek odyssey to the place that has been the birth place for democracy and a cradle of civilization. Great motorcycle riding on some of the best motorbike roads in Greece, all topped with traditional food and drinks, history, culture, nature, beaches, relaxation. itinerari 1 - Thessaloniki Airport Makedonia - Salònica - 30 Motorcycle Tour Greece - a dream has come true. Our English speaking guide will welcome you at Thessaloniki Airport. Transfer to the Hotel for your complimentary night. In the evening meat the Team, pick up your motorbike for the next Greek motorcycle adventure and attend the briefing. 2 - Salònica - Platamon - 184 Start your adventure riding to Karitsa. Visit Dion Archeological Park at the foot at Mount Olympus. Alexander the Great used to bring offerings to the Gods here, prior to military expeditions. Continue your journey to the Home of the mythological Greek Gods – enjoy a motorbike ride to Greece’s Highest Mountain - Olympus. If the motorbikes would have existed back in the times, the Greek hero Hercules would have ridden one, for sure. Accommodation on Olympian Bay. 3 - Platamon - Làmia - 310 Continue your journey to the Meteora. Ride to the to the middle of the sky to the famous Complex of Greek Monasteries at Meteora – UNESCO World Heritage Site. Evening in Lamia in this wonderful motorcycle tour Greece. 4 - Làmia - Atenes - 275 Ride to the foot of Mount Parnassos to Delphi – the centre of unity of the ancient Greek World, where the Oracle of Apollo once spoke. -

Discover Athens, Greece Top 5

Discover Athens, Greece Photo: Anastasios71/Shutterstock.com Of all Europe’s historical capitals, Athens is probably the one that has changed the most in recent years. But even though it has become a modern metropolis, it still retains a good deal of its old small town feel. Here antiquity meets the future, and the ancient monuments mix with a trendier Athens and it is precisely these great contrasts that make the city such a fascinating place to explore.The heart of its historical centre is the Plaka neighbourhood, with narrow streets mingling like a labyrinth where to discover ancient secrets. Anastasios71/Shutterstock.com Top 5 1. Roman Agora During the antiquity, the Agora played a major role as both a marketplace and … 2. National Archaeological Museum The National Archaeological Museum, in Exarchia, is home to 3. The Acropolis and its surround The Parthenon, the temple of Athena, is the major city attraction as well as... Anastasios71/Shutterstock.com 4. Benaki Museum of Greek Culture Benaki is a history museum with Greek art and objects from the 5. Mount Lycabettus Mount Lycabettus (in Greek: Lykavittos, Λυκαβηττός) lies right in the centre... Milan Gonda/Shutterstock.com Athens THE CITY DO & SEE Nick Pavlakis/Shutterstock.com Anastasios71/Shutterstock.com Athens’ heyday was around 400 years BC, that’s Dive in perhaps the most historically rich capital when most of the classical monuments were of Europe and discover its secrets. Athens' past built. During the Byzantine and Turkish eras, the and its landmarks are worldly famous, but the city decayed into just an insignicant little city ofiers much more than the postcards show: village, only to become the capital of it is a vivid city of culture and art, where the newly-liberated Greece in 1833. -

PAUL TANNERY, Quadrivium De Georges Pachymere, Ou Το

1 Madonna Pantanassa Church at Monastiraki Square (Athens) : architectural research and proposals for the revival of the “invisible” historical data Dott. NIKOLIA IOANNIDOU Architect and Architectural and Urban Planning Historian Ph.D, IUAV (Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia 1998) MA, Università di Roma “La Sapienza” Dipl. Arch. Eng., Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 1975. IOANNIS CHANDRINOS Civil Engineer Raymond Lemaire International Centre for Conservation, Leuven (Belgium) “ Advanced Studies in Restoration of Monuments and Sites” Dipl. Engineer, University of Patras, Abstract Athens’s historical center consists of three zones: the oldest archaeological center around Acropolis, the Byzantine and Ottoman ones up to 1833, and the most recent part of the city, outside the classical and Roman walls. Athens’s historical center in a permanent state of crisis. Installing a continuous monitoring system, in order to obtain at real time and any moment information for its state of conservation. Cause to continuous basements trembling, related to vibrations caused by the Metro and the Railway Monastiraki Station, but also to the history through the centuries as described above, the impression of being a living monument - entity, is evident. This paper aims also to emphasize to the actual state and the revival of the “invisible” Monastiraki Square and of the medieval church of Panaghia Pantanassa (Assumption of the Virgin) (Fig.1,2). Figure 1. Church of Madonna Pantanassa. Western facade, actual state Figure 2. Madonna Pantanassa church, drawing of main western facade, design, incorporated Corinthian capitals at the angles (André-Louis Couchaud, 1842) Acknowledgments Based on our participation at 18th ICOMOS General Assembly and Scientific Symposium 10 – 14 November 2014, Florence, Italy, “Heritage and Landscape as Human Values” Before proceeding to the development of the main text of our paper we wanted to express our acknowledgment towards Icomos organizing Committee. -

Ground Metro Vibration and Ground-Borne Noise in Athens Centre: the Case of the Kerameikos Archaeological Museum and Gazi Cultural Centre

Protection of the Cultural Heritage from Under- ground Metro Vibration and Ground-Borne Noise in Athens Centre: The Case of the Kerameikos Archaeological Museum and Gazi Cultural Centre Konstantinos Vogiatzis University of Thessaly, Department of Civil Engineering, Pedion Areos, 383 34 Volos, Greece (Received August 8, 2011, Accepted December 8, 2011) This paper describes the assessment, implementation and verification of the necessary mitigation measures for the protection of the Hellenic cultural heritage of the Kerameikos Museum and archaeological area and the Gazi Cultural Centre in Athens centre from vibration and ground-borne noise during the operation of underground Metro line 3 (Monastiraki to Egaleo). The aim of this article is to present a state-of-the-art assessment and evaluation, through an extended measured program, of the behavior of the implemented mitigation measures in each sensitive archaeological artifacts in the area along the extension alignment. In order to reach this objective, the relevant Athens Metro line section was divided into homogeneous sections (i.e., sections along which the tunnel and soil types, depth and distance from nearby buildings, and presence or not of a switch were considered as constant). Particular emphasis was placed on sections in direct contact with the most important archaeological artifacts, such as the museum and other relevant cultural uses. Data from the relevant prediction model were evaluated on the basis of a complete measurement campaign during Metro operation in the area. The implemented fully floating slab solution, according to the measurement results during Athens Metro operation, recorded levels of ground- borne noise and vibration well within the severe criteria imposed for the Kerameikos area and Museum (as well as for the Gazi Cultural Centre and radio station), both at soil surface locations and on marble statues and various artifacts on glass shelves in the Museum. -

Invitation ATHENS, APRIL 2–4, 2015

Invitation MUSEUM PROFESSIONALS IN DIALOGUE IX : HISTORICAL AND ETHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF GREECE / NATIONAL HISTORICAL MUSEUM ATHENS, APRIL 2–4, 2015 The International Association of History Museums is organising a visit and round table meeting for museum professionals to the Historical and Ethnological Society of Greece / National Historical Museum, Old Parliament Building, Stadiou str. 13, Athens 10561. All IAMH members are invited to participate. The visit starts at 10.00 a.m. With this workshop, we would like to introduce a new series of workshops, slightly changed in a way to improve our visits and to include more participants. About the National Historical Museum of Greece Since 1960 the Museum is housed permanently at the Old Parliament building of Athens (Kolokotronis Square). It presents the history of modern Greece: the period of Ottoman and Frankish rule, the Revolution of 1821, the various liberation struggles, the creation of an independent state, the political, social and spiritual development of Hellenism up to today. The permanent exhibition, through paintings and prints, flags and weapons, personal items, documents and photos, utensils and tools as well as traditional costumes and works of modern Greek craftsmanship, depicts the history of Hellenism beginning with the symbolic date of the fall of Constantinople (1453) up to the Greco-Italian War of 1940–1941. This visit is in continuation of the very successful previous such visits by our Association to the House of Terror Museum in Budapest (2005), the Museu d’Historia de Catalunya in Barcelona (2007), the Musée International de la Réforme in Geneva (2008), the STAM City Museum in Ghent (2009), the Musées Gadagne in Lyon (2010), the Historisches Museum Luzern (2011), the Basel Historical Museum (2012) and Museum aan de Stroom in Antwerp (2014).