Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Flight and Hand Imagery

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Graduate Thesis Collection Graduate Scholarship 1995 Flight and Hand Imagery Jennifer L. Fosnough-Osburn Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Fosnough-Osburn, Jennifer L., "Flight and Hand Imagery" (1995). Graduate Thesis Collection. 23. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses/23 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Department of BUTLER English Language and Literature UNIVERSITY 4600 Sunset Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana 46208 317/283-9223 Name Of Candidate: Jennifer Osburn Oral Examination: Date: June 7, 1995 committee: /'/1' / .. - ( , Chairman ) J T Title: Flight And Hand Imagery In Toni Morrison's Novels Thesis Approved In Final Form: Date: Major Flight and Hand Imagery ID Toni Morrison's Novels Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English Language and Literature of Butler University. August 1995 Jennifer L. Fosnough Osburn r ';- I ·,0 J'I , 1:J",.....11 Introduction By using familiar imagery, such as flight imagery and hand gestures, Toni Morrison reaches out to her audience and induces participation and comprehension. Morrison's critics have a great deal to say about flight imagery as it pertains to The Bluest Eye (1969), Sula (1973), and , Song of Solomon (1977). Her subsequent novels include: Tar Baby (1981), Beloved (1987), and ,.'I ~ (1992). -

Migos Culture 2 Album Download Zip ALBUM: Migos – Culture III

migos culture 2 album download zip ALBUM: Migos – Culture III. Culture III is the upcoming fourth studio album by American hip hop trio Migos, scheduled to be released on the 11th of June 2021. It will follow up 2018’s Culture II and each member’s debut solo studio albums, released between October 2018 and February 2019. DOWNLOAD MP3. About Migos Migos are an American hip hop trio from Lawrenceville, Georgia, founded in 2008. They are composed of three rappers known by their stage names Quavo, Offset, and Takeoff. Migos Culture 3 Album Tracklist. Culture iii by Migos features some top hip hop Stars including Drake Justin Bieber, Juice Wrld, Pop Smoke, NBA Youngboy Never Broke Again, Future, Polo G. Stream & Download Migos – Culture III Album Zip & Mp3 Below: DOWNLOAD Zip : Migos Culture 3 Album Download. Download Zip Culture 3 by Migos, RCA Records & Sony Music Entertainment, Hip-Hop/Rap music maker Migos shares new tracks, of album project titled “Culture 3” and is here for your easy & fast download. (Mp3–320kbps / Includes unlimited streaming via iTunes Plus high-quality download in FLAC AAC M4A CDQ Descarger torrent ZippyShare mp3-direct). Full Album: Culture 3 by Migos song free download is out now on toryextra listen/share with friends. DOWNLOAD ALBUM ZIP LINK. DOWNLOAD ALBUM ZIP LINK. 1.Avalanche 2.Having Our Way ft. Drake 3.Straightenin 4.Type Shit ft. Cardi B 5.Malibu ft. Polo G 6.Birthday 7.Modern Day 8.Vaccine 9.Picasso ft. Future 10.Roadrunner 11.What You See ft. Justin Bieber 12.Birkin 13.Antisocial ft. -

Time As Geography in Song of Solomon

TIME AS GEOGRAPHY IN SONG OF SOLOMOS CARMEN FLYS JUNQUERA C.E.N.UA.H. (Resumen) En Song of Salomón vemos personajes con sentido de geografía, de localización, conscientes de su fracaso e identidad. Quien carece de este sentido de lugar, de un pasado, se encontrará perdido y confuso. Se analiza aquí el viaje hacia la búsqueda de identidad del personaje principal, Milkman, según las tres fases del tradicional "romance quest". Geografía y tiempo se unen para encontrar, al fin, la identidad en el pasado. La búsqueda culmina al aceptar su pasado, la tierra de los antepasados y su cultura, para poder así llegar a entender el futuro. Toni Morrison ve su triunfo como no sólo personal, sino el de la comutúdad afro-americana que lucha por no perder su identidad cultural. One of the characteristics of Toni Morrison's fiction is the use of geography. Her characters, plots and themes are intimately related with the place where they Uve or take place. This relationship is delibérate on her part as she clearly states m an interview: "When the locality is clear, fuUy realized, then it becomes universal. I knew there was something I wanted to clear away in writing, so I used the geography of my childhood, the imagined characters based on bits and pieces of people, and that was a statement."' Morrison's background was special. Ohio has a curious location, it has a border with the South, the Ohio River, yet it also borders with the extreme North, Canadá. Lorain, Ohio is neither the modern urban ghetto ñor the traditional plantation South. -

Smith Alumnae Quarterly

ALUMNAEALUMNAE Special Issueue QUARTERLYQUARTERLY TriumphantTrT iumphah ntn WomenWomen for the World campaigncac mppaiigngn fortififorortifi eses Smith’sSSmmitith’h s mimmission:sssion: too educateeducac te wwomenommene whowhwho wiwillll cchangehahanngge theththe worldworlrld This issue celebrates a stronstrongerger Smith, where ambitious women like Aubrey MMenarndtenarndt ’’0808 find their pathpathss Primed for Leadership SPRING 2017 VOLUME 103 NUMBER 3 c1_Smith_SP17_r1.indd c1 2/28/17 1:23 PM Women for the WoA New Generationrld of Leaders c2-50_Smith_SP17.indd c2 2/24/17 1:08 PM “WOMEN, WHEN THEY WORK TOGETHER, have incredible power.” Journalist Trudy Rubin ’65 made that statement at the 2012 launch of Smith’s Women for the World campaign. Her words were prophecy. From 2009 through 2016, thousands of Smith women joined hands to raise a stunning $486 million. This issue celebrates their work. Thanks to them, promising women from around the globe will continue to come to Smith to fi nd their voices and their opportunities. They will carry their education out into a world that needs their leadership. SMITH ALUMNAE QUARTERLY Special Issue / Spring 2017 Amber Scott ’07 NICK BURCHELL c2-50_Smith_SP17.indd 1 2/24/17 1:08 PM In This Issue • WOMEN HELPING WOMEN • A STRONGER CAMPUS 4 20 We Set Records, Thanks to You ‘Whole New Areas of Strength’ In President’s Perspective, Smith College President The Museum of Art boasts a new gallery, two new Kathleen McCartney writes that the Women for the curatorships and some transformational acquisitions. World campaign has strengthened Smith’s bottom line: empowering exceptional women. 26 8 Diving Into the Issues How We Did It Smith’s four leadership centers promote student engagement in real-world challenges. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENTS OF AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES, ENGLISH, AND WOMEN’S, GENDER, AND SEXUALITY STUDIES LIVING HISTORY: READING TONI MORRISON’S WORK AS A NARRATIVE HISTORY OF BLACK AMERICA ELIZABETH CATCHMARK SPRING 2017 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in African American Studies, English, Women’s Studies, and Philosophy with interdisciplinary honors in African American Studies, English, and Women’s Studies. Reviewed and approved* by the following: Kevin Bell Associate Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Marcy North Associate Professor of English Honors Adviser AnneMarie Mingo Assistant Professor of African American Studies and Women’s Studies Honors Adviser Jennifer Wagner-Lawlor Associate Professor of English and Women’s Studies Honors Advisor * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT Read as four volumes in a narrative retelling of black America, A Mercy, Beloved, Song of Solomon, and Love form a complex mediation on the possibilities for developing mutually liberating relationships across differences of race, class, and gender in different historical moments. The first two texts primarily consider the possibilities for empathy and empowerment across racial differences, inflected through identities like gender and class, while the latter two texts unpack the intraracial barriers to building and uplifting strong black communities. In all texts, Morrison suggests the most empowering identity formations and sociopolitical movements are developed in a coalitional vision of black liberation that rejects capitalism, patriarchy, and white supremacy as mutually constitutive systems. Central to this theme is Morrison’s sensitivity to the movements of history, how the particular social and political contexts in which her novels take place shape the limitations and possibilities of coalitions. -

Quavo New Album Track List Mp3 Download T-Man Releases the “My Journey” Album

quavo new album track list mp3 download T-Man releases the “My Journey” Album. T-Man comes through with a brand new album titled “My Journey”. Since he hit the SA music scene, T-Man has been on a journey to be recognized for what he does. Over time, that has paid off because he has attracted the right kind of attention to himself and also to his music. He has got a list of credits for his works with Babes Wodumo, Mampintsha, Mshayi, Mr Thela and more. His music is undeniably from the heart just like those of the people who inspire him, Brenda Fassie and Rmashesha. He’s out now with a album detailing his journey. He calls it “The Journey”. It features 10 tracks and contributions from Mshayi, Mr Thela, LuXman and more. T-Man “My Journey” Album Tracklist. NO Title Artist Time 1 Sorry Sisi (feat. Mshayi & Mr Thela) T-Man 6:30 2 LaLiga (feat. Mshayi & Mr Thela) T-Man 5:37 3 Elinyithuba (feat. Mshayi & Mr Thela) T-Man 6:11 4 eRands (feat. Mshayi, Mr Thela & Ma-owza) T-Man 5:37 5 Nwabisa (feat. Mshayi, Mr Thela & Charlie Magandi) T-Man 5:20 6 Sugarjuly Anthem (feat. Mshayi, Mr Thela & Sugar) T-Man 4:05 7 Gandaganda (feat. Cruel Boyz) T-Man 5:37 8 Camera Man (feat. LuXman) T-Man 5:48 9 Emakoneni (feat. LuXman) T-Man 4:49 10 Bignuz (feat. Siboniso Shozi & LuXman) T-Man 6:05. From start till finish, you realise just what an amazing project it is. -

Quiet Talks on Prayer

Quiet Talks on Prayer Author(s): Gordon, Samuel Dickey (1859-1936) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Never has a discussion on prayer been as open and honest as it is in S.D. Gordon's Quiet Talks on Prayer. Quiet Talks brings fresh thought and insight to a topic that Christians are familiar with, but may not always understand. Gordon delves into the power, importance, and difficulties of prayerÐand uses Christ's prayer habits as a guide for our own improve- ment.This book is perfect for those yearning to improve their understanding of prayer as a spiritual discipline while strengthening their relationship with God. Luke Getz CCEL Staff Writer i Contents Title Page 1 I. The Meaning and Mission of Prayer 2 Prayer the Greatest Outlet of Power 3 Prayer the Deciding Factor in a Spirit Conflict 12 The Earth, the Battle-Field in Prayer 16 Does Prayer Influence God? 22 II. Hindrances to Prayer 30 Why the Results Fail 31 Why the Results are Delayed 37 The Great Outside Hindrance 48 III. How to Pray 57 The "How" of Relationship 58 The "How" of Method 65 The Listening Side of Prayer 73 Something about God's Will in Connection With Prayer 82 May we Pray With Assurance for the Conversion of Our Loved Ones 88 IV. Jesus' Habits of Prayer 95 Jesus' Habits of Prayer 96 Dissolving Views. 98 Deepening Shadows. 102 Under the Olive Trees. 106 A Composite Picture. 109 ii This PDF file is from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library, www.ccel.org. -

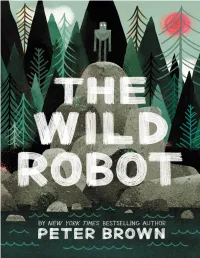

The Wild Robot.Pdf

Begin Reading Table of Contents Copyright Page In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. To the robots of the future CHAPTER 1 THE OCEAN Our story begins on the ocean, with wind and rain and thunder and lightning and waves. A hurricane roared and raged through the night. And in the middle of the chaos, a cargo ship was sinking down down down to the ocean floor. The ship left hundreds of crates floating on the surface. But as the hurricane thrashed and swirled and knocked them around, the crates also began sinking into the depths. One after another, they were swallowed up by the waves, until only five crates remained. By morning the hurricane was gone. There were no clouds, no ships, no land in sight. There was only calm water and clear skies and those five crates lazily bobbing along an ocean current. Days passed. And then a smudge of green appeared on the horizon. As the crates drifted closer, the soft green shapes slowly sharpened into the hard edges of a wild, rocky island. The first crate rode to shore on a tumbling, rumbling wave and then crashed against the rocks with such force that the whole thing burst apart. -

Toni Morrison's Hero

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Göteborgs universitets publikationer - e-publicering och e-arkiv ENGLISH Toni Morrison’s Hero A Song of Solemn Men Chris Rasmussen Supervisor: Chloé Avril BA Thesis Examiner: Fall 2013 Margrét Gunnarsdóttir Champion Title: Toni Morrison’s Hero: A Song of Solemn Men Author: Chris Rasmussen Supervisor: Chloé Avril Abstract: This essay claims Song of Solomon is an example of a hero’s journey, aligned with the narratological features of the genre. Through an analysis of comradeship as the virtue of the quest, the hero’s identity within family, gender and geography becomes a function of access to ancestry. Morrison claims these elements and protagonist Milkman’s quest engenders an African American claim on the hybrid American mythology. Key Words: Song of Solomon, Toni Morrison, hero’s journey, quest narrative, quest genre, family, gender, geography, African American diaspora, mythology Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Research & Method 3 2. Mythology and an African American family 4 2.1 What is an idea virtuous? 6 2.2 Who is a virtuous hero? 7 3. Comradeship, People and Places 9 3.1 How comradeship is achieved 11 3.2 How comradeship collapses 13 4. A Hero’s Journey 17 4.1 Assembling a Quest 18 4.2 Actions of a Hero 19 4.3 The question of a Heroine 22 5. Conclusion & Future Research 25 Bibliography 26 1. Introduction “A good cliché can never be overwritten, it’s still mysterious.” -Conversations with Toni Morrison, 160 The writing of Song of Solomon (1977) followed the death of the author’s father. -

ACLU PLEDGES SUPPORT- for GAYS by John Stilwell Liberties

News of Interest to the Lesbia�/Gay Community FREE! Volume 5, Number 6 Memphis, Tennessee June, 1984 ACLU PLEDGES SUPPORT- FOR GAYS by John Stilwell liberties. Other sources of income a lot of support from the·ACLU ACLU will have a speaker at the In Aoril '84. Ric Sullivan was include an annual junk sale, indi- in terms of research into laws Gay Pride Rally on June 30, and elected as the President of the vidual contributions and most and discrimination and lobbying Sullivan will encourage board Board of Directors of the West important, memberships. support," Sullivan said. In the members and members at large to Tennessee Chapter of the ACL U Last year, due to cash flow upconingyear he is stressing that attend the rally as a showof sup which is one of many chapters problems, there was serious con- we "continue to maintain and re- port for the local Gay rights which make up the state affiliate. sideration given to closing the lo- establish close ties with other or- movement. According to Sullivan, "Our cal ACLU office here in Mem- ganizations in the community , Sullivan said, "I would like to primaryre sponsibilityis of course phis, which provides the chapter . that have very similar goals to thank the Memphis Gay Commu to work for civil li�erties in the with financial, clerical, and inves- - ours, including the MGC and nity and especially Gaze and the : West Tennessee area. Another tigative support. However, Sulli- N.O.W. The ACLU of West Tenn- MGC for all the support they've very importantresponsibility is to van assured Gaze that due to fund essee has long had a very close given the ACLU over the past meet the chapter's commitment to raising and contributions from relationship with the MGC and I years. -

Singer Songwriter Musician Entrepreneur

enya K K Singer Songwriter Musician Entrepreneur WWW.KENYAMJMUSIC.COM Kenya's BIOGRAPHY Singer/songwriter Kenya delivers smooth, soulful vocals with a jazz influence that creates a contemporary groove. Kenya's music has charted in the US Top 30 Billboard Urban Adult Contemporary charts, Top 50 Smooth Jazz independent charts and top 10 on the independent UK Soul Chart in which her previous album My Own Skin (2015) reached the #1 spot for four consecutive weeks. Similarly, she reached the #1 spot in Chicago's R&B/Soul ReverbNation chart (August 2018) and was the 2014 recipient of the Black Women in Jazz "Best Black Female 'Rising Star' Jazz Artist" award. Opening for such recording artists as Lalah Hathaway, Rachelle Ferrell, Raul Midon, Mint Condition's Stokley Williams and Algebra Blessett, Kenya delights diverse crowds with her melodic tone and engaging stage presence. A graduate of Howard University and former member of the university's Howard Gospel Choir, Kenya is now based in Chicago and has performed internationally at noteworthy venues and festivals including Essence Festival, Capital Jazz Super Cruise, Magic CIty Smooth Jazz in the Park Series in Alabama, Washington D.C.'s Blues Alley, Denver's Dazzle Jazz Club, The Biltmore in LA, Groove NYC, Atlanta's St. James Live, The Promontory in Chicago in addition to a variety of other Chicago area venues and showcases, London's Jazz Cafe, Manchester, UK's Band on the Wall and a variety of other international settings. Kenya's most recent collaboration with legendary smooth jazz saxophonist, Gerald Albright is a rearrangement of the classic song "My Favorite Things" and is a stellar example of her progressive musical ideas and talent.