Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palakkad Page 1

Palakkad Palakkad School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 21001 Alathur C. G. H. S. S. Vadakkenchery 21002 Alathur M. M. H. S. Panthalapadam 21003 Alathur C. A. H. S. Ayakkad 21004 Alathur P. K. H. S. Manhapra 21005 Alathur S. J. H. S. Puthukkode 21006 Alathur G. H. S. S. Kizhakkanchery 21007 Alathur S. M. M. H. S. Pazhambalacode 21008 Alathur K. C. P. H. S. S. Kavassery 21009 Alathur A. S. M. H. S. Alathur 21010 Alathur B. S. S. G. H. S. S. Alathur 21011 Alathur G. H. S. S. Erimayur 21012 Alathur G. G. H. S. S. Alathur 21013 Coyalmannam C. A. H. S. Coyalmannam 21014 Coyalmannam H. S. Kuthanur 21015 Coyalmannam G. H. S. Tholanur 21016 Coyalmannam G. H. S. S. Kottayi 21017 Coyalmannam G. H. S. S. Peringottukurussi 21018 Coyalmannam G. H. S. S. Thenkurussi 21019 Kollengode G. H. S. S. Koduvayur 21020 Alathur G. H. S. Kunissery 21021 Kollengode V. I. M. H. S. Pallassana 21022 Alathur M. N. K. M. H. S. S. Chittilancheri 21023 Alathur C. V. M. H. S. Vanadazhi 21024 Alathur L. M. H. S. Magalamdam 21025 Kollengode S. M. H. S. Ayalur 21026 Kollengode G. G. V. H. S. S. Nemmara 21027 Kollengode G. B. H. S. S. Nemmara 21028 Kollengode P. H. S. Padagiri 21029 Kollengode R. P. M. H. S. Panangatiri 21030 Kollengode B. S. S. H. S. S. Kollengode 21031 Kollengode V. M. H. S. Vadavanur 21032 Kollengode G. H. S. S. Muthalamada 21033 Kollengode M. H. S. Pudunagaram 21034 Chittur C. A. -

District Wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt

District wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt. Model HSS For Boys Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42007 Govt V H S S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42008 Govt H S S For Girls Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42010 Navabharath E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42011 Govt. H S S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42012 Sr.Elizabeth Joel C S I E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42013 S C V B H S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42014 S S V G H S S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42015 P N M G H S S Koonthalloor Thiruvananthapuram 42021 Govt H S Avanavancheri Thiruvananthapuram 42023 Govt H S S Kavalayoor Thiruvananthapuram 42035 Govt V H S S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42051 Govt H S S Venjaramood Thiruvananthapuram 42070 Janatha H S S Thempammood Thiruvananthapuram 42072 Govt. H S S Azhoor Thiruvananthapuram 42077 S S M E M H S Mudapuram Thiruvananthapuram 42078 Vidhyadhiraja E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42301 L M S L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42302 Govt. L P S Keezhattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42303 Govt. L P S Andoor Thiruvananthapuram 42304 Govt. L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42305 Govt. L P S Melattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42306 Govt. L P S Melkadakkavur Thiruvananthapuram 42307 Govt.L P S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42308 Govt. L P S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42309 Govt. L P S Madathuvathukkal Thiruvananthapuram 42310 P T M L P S Kumpalathumpara Thiruvananthapuram 42311 Govt. L P S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42312 Govt. L P S Mullaramcode Thiruvananthapuram 42313 Govt. L P S Ottoor Thiruvananthapuram 42314 R M L P S Mananakku Thiruvananthapuram 42315 A M L P S Perumkulam Thiruvananthapuram 42316 Govt. -

Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, Kalady Strengthening Of

Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, Kalady Strengthening of Sanskrit Studies Sanskrit Scholarship List 2018-2019 Education District : - Trivandrum -- Sub Districts : Neyyattinkara Sl.No. Name of Students Name of School Class Amount Signature ANJALI B.S. L.M.S.H.S.S., AMARAVILA 1 V 500/- VAISHNAV M.R. K.P.G.H.S., KAZHIVOOR 2 V 500/- ADITHYAN M. P.V.U.P.S., THATHIYOOR 3 VI 500/- MAHIVA SUDEV M.V.H.S., ARUMANOOR 4 VI 500/- KIRAN K.S. G.K.P.G.H.S., KAZHIVOOR 5 VII 500/- VIJITHRA S. NAIR P.V.U.P.S., THATHIYOOR 6 VII 500/- Education District : - Trivandrum -- Sub Districts : Attingal Sl.No. Name of Students Name of School Class Amount Signature ADITHYAN V. G.TOWN U.P.S., ATTINGAL 1 V 500/- KARTHIK KRISHNA G.U.P.S., PALAVILA 2 V 500/- ADITHYA DINESH T. V.P.U.P.S., AZHUOOR 3 VI 500/- GANGA JAYAN G.U.P.S., PALAVILA 4 VI 500/- ANANDHA KRISHNAN G.TOWN U.P.S., ATTINGAL 5 VII 500/- Page 1 Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, Kalady Strengthening of Sanskrit Studies Sanskrit Scholarship List 2018-2019 RESHMA RAJ G. G.U.P.S., PALAVILA 6 VII 500/- Education District : - Trivandrum -- Sub Districts : Kilimanoor Sl.No. Name of Students Name of School Class Amount Signature SNEHA S NAIR C.N.P.S.U.P.S., MADAVOOR 1 V 500/- MEENAKSHY G.R. S.V.P.S., PULIYOORKONAM 2 V 500/- GOURI V.M. C.N.P.S.U.P.S., MADAVOOR 3 VI 500/- HARICHANDRAN P.K. -

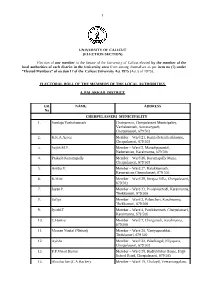

1 P UNIVERSITY of CALICUT (ELECTION SECTION)

1 1 p UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT (ELECTION SECTION) Election of one member to the Senate of the University of Calicut elected by the member of the local authorities of each district in the University area from among themselves as per item no (7) under “Elected Members” of section 17 of the Calicut University Act 1975 (Act 5 of 1975). ELECTORAL ROLL OF THE MEMBERS OF THE LOCAL AUTHORITIES 4. PALAKKAD DISTRICT ER. NAME ADDRESS No CHERPULASSERI MUNICIPALITY 1. Sreelaja Vazhakunnath Chairperson, Cherpulasseri Municipality, Vazhakunnath, Secretarypadi, Cherpulasseri, 679 503 2. K.K.A.Azeez Member – Ward 21, Kunnath Kacherikkunnu, Cherpulasseri, 679 503 3. Sujith.M.P. Member – Ward 5, Manadiparambil, Naduvattom, Karalmanna, 679 506 4. Prakash Kurumapally Member – Ward 26, Kurumapally Mana, Cherpulasseri, 679 503 5. Anitha.V. Member – Ward 27, Kalakkunnath, Kavuvattom,Cherpulasseri, 679 503 6. K.Mini Member – Ward 29, Sreejaa Villa, Cherpulasseri, 679 503 7. Jayan.P. Member – Ward 33, Poolakkathodi, Karalmanna, Thekkumuri, 679 506 8. Safiya Member – Ward 2, Palancheri, Karalmanna, Thekkumuri, 679 506 9. Jyothi.T Member – Ward 4, Pattikkunnath, Cherpulasseri, Karalmanna, 679 506 10. C.Hamza Member – Ward 7, Chinganadi, Karalmanna, 679 506 11. Meeran Noufal (Nishad) Member – Ward 20, Vaniyapurakkal, Thrikkatteri, 679 502 12. Ayisha Member – Ward 22, Palathingal, Eliyapatta, Cherpulasseri, 679 503 13. P.P.Vinod Kumar Member – Ward 28, Kudiyirikkal House, High School Road, Cherpulasseri, 679 503 14. Aboobacker (C.A.Backer) Member – Ward 19, Cholayil, Veeramangalam, 2 679 503 15. Saddique Hussain Member – Ward 11, Velliyappanthodi, Karumanamkurissi, 679 504 16. Suharabi Member – Ward 12, Valiyaparambil, Station Hill, Mandakkari, Cherplusseri, 679 503 17. -

Notice for Appointment of REGULAR/RURAL Retail Outlet Dealerships

Notice for appointment of REGULAR/RURAL Retail Outlet Dealerships Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (BPCL) Proposes to appoint retail outlet dealers in Kerala State as per the following details Fixed Fee Estimated / Type of monthly Minimum Dimension (in M.)/Area of Finance to be arranged Rs in lakh Mode of Security Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Category Type of Site* Minimum RO Sales the site (in Sq. M.). * by the applicant Selection Deposit Bid Potential # amount 1 2 345 6 78 9a 9b101112 SC/SC CC-1/SC CC-2/SC Estimated fund Estimated PH/ST/ST CC-1/ST CC- required for Draw of Regular / MS+HSD in working capital (Rs.in (Rs.in 2/ST PH/OBC/OBC CC- CC / DC / CFS Frontage Depth Area development of Lots / Rural Kls requirement for Lakh) Lakh) 1/OBC PH/OPEN/OPEN CC- infrastructure at Bidding operation of RO 1/OPEN CC-2/OPEN PH RO Draw of 1 ATHOLI KOZHIKODE RURAL 200 OPEN DC 30 25 750 12 30 Lots 5 4 Draw of 2 Anjarakkandy KANNUR RURAL 155 OBC DC 30 25 750 12 30 Lots 5 3 Draw of 3 Erikulam KASARAGOD RURAL 90 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Between Cheparamba and Draw of 4 Chemberi KANNUR RURAL 45 OPEN DC 30 25 750 12 30 Lots 5 4 Between Kumbala and Draw of 5 Badiyadukka KASARAGOD RURAL 125 OPEN DC 30 25 750 12 30 Lots 5 4 Draw of 6 Ariyallur MALAPPURAM RURAL 95 OBC DC 30 25 750 12 30 Lots 5 3 Draw of 7 SREEKRISHNAPURAM PALAKKAD RURAL 83 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 8 Chakkittappara KOZHIKODE RURAL 100 OPEN DC 30 25 750 12 30 Lots 5 4 Draw of 9 CHEKKIKULAM KANNUR RURAL 95 OPEN DC 30 25 750 12 30 Lots 5 4 Draw of 10 BALAL VILAGE -

Phone No: 9744443057, 8281729725 208/1 Mobile :9387805668

APPLICATION FOR ENVIRONMENTAL CLEARANCE FOR GRANITE BUILDING STONE QUARRY PROJECT (As per EIA Notification 2006 and amendments thereof) Form-IM, PFR & EMP Proponent/Applicant MANNARKKAD TALUK KARINKAL QUARRY OPERATORS INDUSTRIAL CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED Pullissery P.O., Mannarkkad Palakkad District (D), Kerala – 678 582 Email ID: [email protected] Phone No: 9744443057, 8281729725 Represented by President, Shri C. H. Sakkariya Site at Re. Survey No : 208/1 Village : Alanallur-3 Taluk : Mannarkkad District : Palakkad State : Kerala Extent : 1.1277 Ha Prepared by V.K. ROY Saral, T.C. 27/487(2), Swaraj Lane, R.C. Junction, Kunnukuzhy, Thiruvananthapuram – 695 035 DMG/KERALA/RQP/4/2016 Mobile :9387805668 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Sl. No. DESCRIPTION Page No. I FORM – IM 4-7 II CHECKLIST FOR MINING PROJECTS 8-19 III QUESTIONNAIRE FOR MINING PROJECTS 20-22 IV PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT 23-42 1. Executive Summary 24 2. Introduction of the Project 26 3. Project Description 29 4. Site Analysis 36 5. Planning Brief 38 6. Proposed Infrastructures 39 7. Rehabilitation & Resettlement (R & R) Plan 41 8. Project Schedule & Cost Estimates 42 9. Analysis of the Proposal (Final Recommentation) 42 V ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN & CSR 43-66 1. Introduction of the Project/Proponent 44 2. Details of the Project 44 3. Baseline Environment 48 4. Environmental Management Plan 52 5. Safety in Blasting 57 6. Mine Closure Plan 58 7. Risk Assessment 59 8. Disaster Management Plan 60 9. Occupational Health & Safety 62 10. Environmental Monitoring Program 63 11. Social (Corporate) Responsibilty 65 12. Conslusion 66 2 Sl. No. DESCRIPTION Page No. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Palakkad District from 01.04.2018 to 07.04.2018

Accused Persons arrested in Palakkad district from 01.04.2018 to 07.04.2018 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kavutheruvu, 435/18 U/s 118 Robinson Town South Sheebu K.V, Bailed by 1 Krishnan Seethalakshmi 32 Sekhareepuram, 01.04.18 (a) KP Act Road PS GASI of Police Police Palakkad Krishnapravee Ramachandra Preyas, Murugani, C N 436/18 U/s 118 Palauappett Town South Sheebu K.V, Bailed by 2 29 01.04.18 n n Puram, Palakkad (a) KP Act a PS GASI of Police Police 437/18 U/s 279 Radhakrishna Kaikuthuparambu, Town South Abdul Gaffur, Bailed by 3 Sanjith 22 IPC & 3 (1) r/w Noorani Jn 01.04.18 n Noorani PS Adl SI of Police Police 181 MV Act 438/18 U/s 283 N S Vihar, Kailas I/F District Town South Abdul Gaffur, Bailed by 4 Akas Rajan 25 IPC & 120 (b) 01.04.18 Nagar, Pudussery Hospital PS Adl SI of Police Police KP Act 439/18 U/s 153, Kaladharan @ Kazhchaparambu, 292 IPC & 120 Kazhchapar Town South Abdul Gaffur, Bailed by 5 Rajan 46 02.04.18 Kala Kannadi, Palakkad (e) KPAct, 67 of ambu PS Adl SI of Police Police IT Act 441/18 U/s 20 Shahul Sakkeer Nishana Manzil, Town South Bailed by 6 Ayyoob 26 (b)(ii)A of Yakkara 02.04.18 Hameed, SI of Hussain Chadanamkurussi PS Police NDPS Act Police 19/882, 442/18 U/s 283 Kamakshiyamman IMA Town South Abdul Gaffur, Bailed by 7 Rameshkumar Selvan 35 IPC & 120 (b) 03.04.18 -

Accused Persons Arrested in Palakkad District from 02.04.2017 to 08.04.2017

Accused Persons arrested in Palakkad district from 02.04.2017 to 08.04.2017 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 413/17 U/s 279 House No. 4, Aishwarya KSRTC Link Sasi P.V, GSI of Bailed by 1 Krishnan Kandu 49 02.04.17 IPC and 185 MV Town South PS Nagar, Noorani Road Police police Act Payarangal House, KSRTC Link 414/17 U/s 118 Sasi P.V, GSI of Bailed by 2 Vinod Ramdas 40 02.04.17 Town South PS Vennakkara, Palakkad Road (a) of KP Act Police police 415/17 U/s 15 Karipali House, Sujith Kumar.R, Bailed by 3 Anil kumar Kandamuthan 26 Karipali 02.04.17 (c) r/w 63 of Town South PS Kodumbu, Palakkad SI of Police police Abkari Act Kalarikkal House, 417/17 U/s 279 Sujith Kumar.R, Bailed by 4 Ashwin Raghavan 26 Midhunampallam, Kodumbu 02.04.17 IPC and 185 of Town South PS SI of Police police Kodumbu, Palakkad MV Act Puthanpura House, 418/17 U/s 279 Sujith Kumar.R, Bailed by 5 Yadhukrishnan Radhakrishnan 27 Thiruvalathur, Kodumbu Jn. 02.04.17 IPC and 185 of Town South PS SI of Police police Kodumbu, Palakkad MV Act 416/17 U/s 15 Kalarikkal House, Sujith Kumar.R, Bailed by 6 Sunilkumar Sukumaran 30 Kodumbu Jn. -

Lii OIIIAIATIIIUZAHVKXI» IOU'l'i'§'L'%Li1‘OIUDM

flH‘I§A1IDflUW@‘lII OIIIAIATIIIUZAHVKXI» IOU'l'I'§'l'%lI1‘OIUDM Theahsubnittedtaothe OOCIIIIIIIVIIIl1'YOIiIlI'D‘l'§ElD01' inpnrtinlfulflhnentofthcmquxirementa forthcdegrecof DOCTOR Q FIDO‘? IN MARINE GEOLOGY UNDER THE FACULTY OF MARINE SCIENCES by lnllumn DEPARTMENT OF MARINE GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS SCHOOL OF MARINE SCIENCES COCHIN UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND ‘TECHNOLOGY COCHIN - 682 0 16 SEPTEMBER, 2009 2>¢¢¢z¢:@¢w»u,4¢em¢4<~4M¢ DECLARATION I, SREELA S. R, do hereby declare that the thesis entitled “AN INTEGRATED STUDY ON THE HYDROGEOLOGY OF BHARATI-IAPUZHA RIVER BASIN, SOUTH WEST COAST OF INDIA” is an authentic record of research work carried out by me under ‘the supervision and guidance of Dr. K. SAJAN, Professor, Department of Marine Geology and Geophysics, School of Marine Sciences, Cochin University of Science and Technology. This work has not been previously formed the basis for the award of any degree or diploma of this or any other University / institute. Sreela@“ S. R Cochin- 16 18-O9- 2009 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “AN INTEGRATED STUDY ON THE HYDROGEOLOGY OF BHARATHAPUZHA RIVER BASIN, SOUTH WEST COAST OF INDIA” is an authentic record of research work carried out by Ms. SREELA S. R under my supervision and guidance in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and no part thereof has been presented for the award of any degree in any University / Institute. Prof. jan {Researc Supervisor) Cochin _16 Prof. Dr. K. SAJAN 18 '09 ‘ Scuoot2 O09 DEPARTMENT OF OCEAN or MARINE SCIENCE Geotosv AND AND Tecuuotoev GEOPHYSICS Cocnm Umvmsnv or SCIENCE AND Tecunotoev FlNE Ams Avenue, Kocm - 682016 iND|A ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I have great pleasure to record my sincere gratitude to my research guide Dr. -

District Census Handbook, Palghat, Part X-A, X B, Series-9

CENSUS 1971 SERIES-9 KERALA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK , ' PALGHAT PART X-A TOWN & VILLAGE DIRECTORY PART X-B PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 1973 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PARTS A & B PALGHAT I , NILGIRIS DISTRICT..... PALGHAT DISTRICT (TAMIL NADU) J ..fLU;O • I l 10 .................. ...._. ........r ~~D3~Ean~~=~-~~~=31- a ti.ii IJi FB3 I , ...... ,i~. 10 • 0 10 "'Lo ... r'flltlS L (, "'" S ""'1 ·... •.... v·r :l ?.. , ~,.."", ' .....:,. MALAPPURAM ,-' ''Y'- DISTRICT i ./ COIMBATORE DISTRICT (TAaML NADU) ... TRICHUR DISTRICT KERALA LEGEND _._. DISTRICT BOUNDARY ""', u::::CRIVER _._._- TALUI< BOUNDARY ~ DISTRICT HEADQUARTERS - NATIONAL HIGHWAY @ TALUk HEADQUARTERS - OTHER IMPORTANT ROAD @ TALlJI( HEADQUARTERS & --RAILWAY- BROAD-GAUGE • TOWN CONTENTS Page Preface Figures at a glance PART A-TOWN AND VILLAGE DIRECTORY Introduction 5 Tovvn Directory 11 Village Directory 19 Taluk-wise abstract of educational, medical ani oth~r a nenities 40 PART B-PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT Introduction 45 Village and Tovvn Primary Census Abstract, Palgha district 53 Ottapalam taluk " 53 Mannarghat taluk 79 " Palghat taluk " 87 Chittur taluk " 105 Alathur taluk " 119 Block-wise and Panchayat-wise Primary Census Abstract 129 Alphabetical list of villages and desomsJkaras (Rural areas) 169 MAPS Palghat district Ottapalam taluk 55 Mannarghat taluk ~l Palghat taluk 89 Chittur taluk 107 Alathur taluk 121 PREFACE The District Census Handbooks were published for the first time in 1951 as part of the Census publication programme. Each Handbook contained a general account of the district and its people, census tables and statistics on the area, houses, population, general amenities and distribution of population by livelihood classes for each village and town. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Palakkad District from 11.05.2014 to 17.05.2014

Accused Persons arrested in Palakkad district from 11.05.2014 to 17.05.2014 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, Rank which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Poolakkal, Cr.679/14 u/s C Chandran, SI of 1 Fousiya Shihabudheen 25/14 Poovarkonam, 12.05.14 Dist.Panchayath Town South PS Bail by Police 160 IPC Police Vaniyamkulam Vattavilayil, Cr.679/14 u/s C Chandran, SI of 2 Sulekha Sabu Ismail 40/14 Perinthalmanna, 12.05.14 Dist.Panchayath Town South PS Bail by Police 160 IPC Police Malappuram Vattavilayil, Cr.679/14 u/s C Chandran, SI of 3 Sabu Ismail Ismail.S.M 45/14 Perinthalmanna, 12.05.14 Dist.Panchayath Town South PS Bail by Police 160 IPC Police Malappuram Poolakkal, Cr.679/14 u/s C Chandran, SI of 4 Shihabudheen Muhammed Sha 31/14 Poovarkonam, 12.05.14 Dist.Panchayath Town South PS Bail by Police 160 IPC Police Vaniyamkulam Cr.681/14 u/s Kunnathurmedu, C Chandran, SI of 5 Prabhu Arumughan 35/14 12.05.14 15 C Abkari Kunnathurmedu Town South PS Bail by Police Cheerakkad, Palakkad Police Act Cr.681/14 u/s Chirakkad, C Chandran, SI of 6 Gunasekharan Chinnaraj 36/14 12.05.14 15 C Abkari Kunnathurmedu Town South PS Bail by Police Kunnathurmedu Police Act Cr.682/14 u/s Kulathingal House, C Chandran, SI of 7 Kannan Chami.V.K 35/14 12.05.14 15 C Abkari Chirakkad Town South PS Bail by Police Edathara, Parli Police Act Nehru Colony, Cr.682/14 u/s -

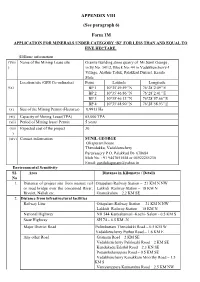

APPENDIX VIII (See Paragraph 6) Form 1M

APPENDIX VIII (See paragraph 6) Form 1M APPLICATION FOR MINERALS UNDER CATEGORY ‘B2’ FOR LESS THAN AND EQUAL TO FIVE HECTARE. (II)Basic information (Viii Name of the Mining Lease site Granite Building stone quarry of Mr.Sunil George , ) in Sy.No: 341/2, Block No: 44 in Vadakkencherry-I Village, Alathur Taluk, Palakkad District, Kerala State Location/site (GPS Co-ordinates) Point Latitude Longitude (ix) BP 1 10°35’49.59’’N 76°28’2.09’’E BP 2 10°35’46.86’’N 76°28’2.41’’E BP 3 10°35’46.13’’N 76°28’57.66’’E BP 4 10°35’48.90’’N 76°28’58.93’’E (x) Size of the Mining Permit (Hectares) 0.9913 Ha (xi) Capacity of Mining Lease(TPA) 65,000 TPA (xii) Period of Mining lease/ Permit 5 years (xiii Expected cost of the project 30 ) (xiv) Contact information SUNIL GEORGE Oliapuram house Thenidukku, Vadakkenchery Paruvassery P O, Palakkad Dt- 678684 Mob No. +91 9447051558 or 04922255230 Email: [email protected] Environmental Sensitivity SI. Area Distance in KiLometre / DetaiLs No 1. Distance of project site from nearest rail Ottapalam Railway Station – 21 KM N NW or road bridge over the concerned River, Lakkidi Railway Station – 18 KM N Rivulet, Nallah etc. Gramakulam – 2.2 KM SE 2. Distance from infrastructural faciLities Railway Line Ottapalam Railway Station – 21 KM N NW Lakkidi Railway Station – 18 KM N National Highway NH 544 Kanyakumari -Kochi- Salem - 0.5 KM S State Highway SH 74 – 6.5 KM -N Major District Road Pulimkuttam Thenidukki Road – 0.5 KM W Vadakkencherry Puthur Road – 1.6 KM E Any other Road Gramam Road – 2 KM SE Vadakkencherry Palakuzhi Road – 2 KM SE Kundukadu Edathil Road – 2.3 KN SE Pottamkulamppara Road – 0.5 KM SE Vadakkencherry Kanakkam Moorthy Road – 1.5 KM S Vaniyamppara Kannambra Road – 2.5 KM NW Kannambra Puthukodu Road – 2.1 KM N Electric Transmission line pole or tower 0.5 KM S Canal or check dam or reservoirs or lake or Mangalam Dam – 12 KM SE ponds Pothundi Dam – 18 KM E SE Peechi Dam – 12 KM SW Vazhani Dam – 18 KM W In take for Drinking water Panchayat Water supply / open well Intake for irrigation Not Available within 100 m surroundings 3.