The Flow of the Neches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Proposed Fastrill Reservoir in East Texas: a Study Using

THE PROPOSED FASTRILL RESERVOIR IN EAST TEXAS: A STUDY USING GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS Michael Ray Wilson, B.S. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2009 APPROVED: Paul Hudak, Major Professor and Chair of the Department of Geography Samuel F. Atkinson, Minor Professor Pinliang Dong, Committee Member Michael Monticino, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Wilson, Michael Ray. The Proposed Fastrill Reservoir in East Texas: A Study Using Geographic Information Systems. Master of Science (Applied Geography), December 2009, 116 pp., 26 tables, 14 illustrations, references, 34 titles. Geographic information systems and remote sensing software were used to analyze data to determine the area and volume of the proposed Fastrill Reservoir, and to examine seven alternatives. The controversial reservoir site is in the same location as a nascent wildlife refuge. Six general land cover types impacted by the reservoir were also quantified using Landsat imagery. The study found that water consumption in Dallas is high, but if consumption rates are reduced to that of similar Texas cities, the reservoir is likely unnecessary. The reservoir and its alternatives were modeled in a GIS by selecting sites and intersecting horizontal water surfaces with terrain data to create a series of reservoir footprints and volumetric measurements. These were then compared with a classified satellite imagery to quantify land cover types. The reservoir impacted the most ecologically sensitive land cover type the most. Only one alternative site appeared slightly less environmentally damaging. Copyright 2009 by Michael Ray Wilson ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to acknowledge my thesis committee members, Dr. -

Distribution of Unionid Mussels in the Big Thicket

DISTRIBUTION OF UNIONID MUSSELS IN THE BIG THICKET REGION OF TEXAS by Alison A. Tarter, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science with a Major in Aquatic Resources May 2019 Committee Members: Astrid N. Schwalb, Chair Thomas B. Hardy Clinton Robertson COPYRIGHT by Alison A. Tarter 2019 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Alison A. Tarter, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my committee chair, Dr. Astrid Schwalb, for introducing me to the intricate world of the unionids. Thank you to committee member Dr. Thom Hardy for having faith in me even when I didn’t. Thank you both for being outstanding mentors and for your patient guidance and untiring support for my research and funding. Thank you both for being there through the natural and atypical disasters that seemed to follow this thesis project. Thank you to committee member Clint Robertson for the invaluable instruction with species identification and day of help in the field. Thank you to David Rodriguez and Stephen Harding for the DNA analyses. -

Stormwater Management Program 2013-2018 Appendix A

Appendix A 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) As required under Sections 303(d) and 304(a) of the federal Clean Water Act, this list identifies the water bodies in or bordering Texas for which effluent limitations are not stringent enough to implement water quality standards, and for which the associated pollutants are suitable for measurement by maximum daily load. In addition, the TCEQ also develops a schedule identifying Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) that will be initiated in the next two years for priority impaired waters. Issuance of permits to discharge into 303(d)-listed water bodies is described in the TCEQ regulatory guidance document Procedures to Implement the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (January 2003, RG-194). Impairments are limited to the geographic area described by the Assessment Unit and identified with a six or seven-digit AU_ID. A TMDL for each impaired parameter will be developed to allocate pollutant loads from contributing sources that affect the parameter of concern in each Assessment Unit. The TMDL will be identified and counted using a six or seven-digit AU_ID. Water Quality permits that are issued before a TMDL is approved will not increase pollutant loading that would contribute to the impairment identified for the Assessment Unit. Explanation of Column Headings SegID and Name: The unique identifier (SegID), segment name, and location of the water body. The SegID may be one of two types of numbers. The first type is a classified segment number (4 digits, e.g., 0218), as defined in Appendix A of the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (TSWQS). -

Environmental Advisory Committee Meeting December 7, 2018 10 A.M

Environmental Advisory Committee Meeting December 7, 2018 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. CRP Coordinated Monitoring Meeting Texas Logperch (Percina carbonaria) https://cms.lcra.org/sch edule.aspx?basin=19& FY=2019 2 Segment 1911 – Upper San Antonio River 12908 SAR at Woodlawn 12909 SAR at Mulberry 12899 SAR at Padre16731 Road SAR Upstream 12908 SAR at Woodlawn 21547 SAR at VFW of the Medina River Confluence 12879 SAR at SH 97 Pterygoplichthys sp. 3 Segment 1901 – Lower San Antonio River 16992 Cabeza Creek FM 2043 16580 SAR Conquista12792 SAR Pacific RR SE Crossing Goliad 12790 SAR at FM 2506 Pterygoplichthys sp. 4 Segment 1905 – Upper Medina River 21631 UMR Mayan 12830 UMR Old English Ranch Crossing 21631 UMR Mayan Ranch 12832 UMR FM 470 5 Segment 1904 Medina Lake & 1909 Medina Diversion Lake Medina Diversion Lake Medina Lake 6 Segment 1903 Lower Medina River 12824 MR CR 2615 14200 MR CR 484 12811 MR FH 1937 Near Losoya 7 Segment 1908 Upper Cibolo Creek 1285720821 UCC NorthrupIH10 Park 15126 UCC Downstream Menger CK 8 Segment 1913 Mid Cibolo Creek 12924 Mid 14212 Mid Cibolo Cibolo Creek Upstream WWTP Schaeffer Road 9 Segment 1902 Lower Cibolo Creek 12802 Lower Cibolo Creek FM 541 12741 Martinez Creek21755 Gable Upstream FM Road 537 14197 Scull Crossing 10 Segment 1910 Salado Creek 12861 Salado Creek Southton 12870 Gembler 14929 Comanche Park 11 Segment 1912 Medio Creek 12916 Hidden Valley Campground 12735 Medio Creek US 90W 12 Segment 1907 Upper Leon Creek & 1906 Lower Leon Creek 12851 Upper Leon Creek Raymond Russel Park 14198 Upstream Leon Creek -

Beach and Bay Access Guide

Texas Beach & Bay Access Guide Second Edition Texas General Land Office Jerry Patterson, Commissioner The Texas Gulf Coast The Texas Gulf Coast consists of cordgrass marshes, which support a rich array of marine life and provide wintering grounds for birds, and scattered coastal tallgrass and mid-grass prairies. The annual rainfall for the Texas Coast ranges from 25 to 55 inches and supports morning glories, sea ox-eyes, and beach evening primroses. Click on a region of the Texas coast The Texas General Land Office makes no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information depicted on these maps, or the data from which it was produced. These maps are NOT suitable for navigational purposes and do not purport to depict or establish boundaries between private and public land. Contents I. Introduction 1 II. How to Use This Guide 3 III. Beach and Bay Public Access Sites A. Southeast Texas 7 (Jefferson and Orange Counties) 1. Map 2. Area information 3. Activities/Facilities B. Houston-Galveston (Brazoria, Chambers, Galveston, Harris, and Matagorda Counties) 21 1. Map 2. Area Information 3. Activities/Facilities C. Golden Crescent (Calhoun, Jackson and Victoria Counties) 1. Map 79 2. Area Information 3. Activities/Facilities D. Coastal Bend (Aransas, Kenedy, Kleberg, Nueces, Refugio and San Patricio Counties) 1. Map 96 2. Area Information 3. Activities/Facilities E. Lower Rio Grande Valley (Cameron and Willacy Counties) 1. Map 2. Area Information 128 3. Activities/Facilities IV. National Wildlife Refuges V. Wildlife Management Areas VI. Chambers of Commerce and Visitor Centers 139 143 147 Introduction It’s no wonder that coastal communities are the most densely populated and fastest growing areas in the country. -

Illustrated Flora of East Texas Illustrated Flora of East Texas

ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS IS PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF: MAJOR BENEFACTORS: DAVID GIBSON AND WILL CRENSHAW DISCOVERY FUND U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE FOUNDATION (NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, USDA FOREST SERVICE) TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT SCOTT AND STUART GENTLING BENEFACTORS: NEW DOROTHEA L. LEONHARDT FOUNDATION (ANDREA C. HARKINS) TEMPLE-INLAND FOUNDATION SUMMERLEE FOUNDATION AMON G. CARTER FOUNDATION ROBERT J. O’KENNON PEG & BEN KEITH DORA & GORDON SYLVESTER DAVID & SUE NIVENS NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY OF TEXAS DAVID & MARGARET BAMBERGER GORDON MAY & KAREN WILLIAMSON JACOB & TERESE HERSHEY FOUNDATION INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT: AUSTIN COLLEGE BOTANICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF TEXAS SID RICHARDSON CAREER DEVELOPMENT FUND OF AUSTIN COLLEGE II OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: ALLDREDGE, LINDA & JACK HOLLEMAN, W.B. PETRUS, ELAINE J. BATTERBAE, SUSAN ROBERTS HOLT, JEAN & DUNCAN PRITCHETT, MARY H. BECK, NELL HUBER, MARY MAUD PRICE, DIANE BECKELMAN, SARA HUDSON, JIM & YONIE PRUESS, WARREN W. BENDER, LYNNE HULTMARK, GORDON & SARAH ROACH, ELIZABETH M. & ALLEN BIBB, NATHAN & BETTIE HUSTON, MELIA ROEBUCK, RICK & VICKI BOSWORTH, TONY JACOBS, BONNIE & LOUIS ROGNLIE, GLORIA & ERIC BOTTONE, LAURA BURKS JAMES, ROI & DEANNA ROUSH, LUCY BROWN, LARRY E. JEFFORDS, RUSSELL M. ROWE, BRIAN BRUSER, III, MR. & MRS. HENRY JOHN, SUE & PHIL ROZELL, JIMMY BURT, HELEN W. JONES, MARY LOU SANDLIN, MIKE CAMPBELL, KATHERINE & CHARLES KAHLE, GAIL SANDLIN, MR. & MRS. WILLIAM CARR, WILLIAM R. KARGES, JOANN SATTERWHITE, BEN CLARY, KAREN KEITH, ELIZABETH & ERIC SCHOENFELD, CARL COCHRAN, JOYCE LANEY, ELEANOR W. SCHULTZE, BETTY DAHLBERG, WALTER G. LAUGHLIN, DR. JAMES E. SCHULZE, PETER & HELEN DALLAS CHAPTER-NPSOT LECHE, BEVERLY SENNHAUSER, KELLY S. DAMEWOOD, LOGAN & ELEANOR LEWIS, PATRICIA SERLING, STEVEN DAMUTH, STEVEN LIGGIO, JOE SHANNON, LEILA HOUSEMAN DAVIS, ELLEN D. -

Chapter 1 Description of the Region

Chapter 1 Description of the Region The East Texas Regional Water Planning Area (ETRWPA) is one of sixteen areas established by the 1997 Texas legislature Senate Bill 1 for the purpose of State water resource planning at a regional level on five- year planning cycles. The first regional water plan was adopted in 2001. Since that time, it was updated in 2006, 2011, and 2016. This plan, the 2021 Regional Water Plan (2021 Plan), is the result of the 5th cycle of regional water planning. Pursuant to the formation of the ETRWPA, the East Texas Regional Water Planning Group (ETRWPG or RWPG), was formed and charged with the responsibility to evaluate the region’s population projections, water demand projections, and existing water supplies for a 50-year planning horizon. The RWPG then identifies water shortages under drought of record conditions and recommends water management strategies. This planning is performed in accordance with regional and state water planning requirements of the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB). This chapter provides details for the ETRWPA that are relevant to water resource planning, including: a physical description of the region, climatological details, population projections, economic activities, sources of water and water demand, and regional resources. A discussion of threats to the region’s resources and water supply, a general discussion of water conservation and drought preparation in the region, and a listing of ongoing state and federal programs in the ETRWPA that impact water planning efforts in the region are also provided. 1.1 General Introduction The ETRWPA consists of all or portions of 20 counties located in the Neches, Sabine, and Trinity River Basins, and the Neches- Trinity Coastal Basin. -

SABINE LAKE AREA Waterways Guide

WATERWAYS GUIDE SABINE LAKE AREA Waterways guide BOATING FACILITIES & SERVICES DIRECTORY FISHING & NAVIGATION INFORMATION h REGULATIONS CHARTS ANCHORAGES 409.985.7822 // visitportarthurtx.com BOAT SAFELY AND ENSURE YOUR WATERCRAFT IS UP TO REQUIRED Standards For information Read The Texas Water Safety Act or contact Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, TX 78744 1.800.792.1112 FOR BOATER EDUCATION ©2019 Sabine Lake Area Cruising Guide 1.800.262.8755 FOR BOAT REGISTRATION AND BOAT INFORMATION or visit www.tpwd.texas.gov/fishboat/boat/safety Sabine Lake Area WATERWAYS GUIDE Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information presented in this guide. However, the Port Arthur Convention & Visitors Bureau claims no liability for any changes or omissions that may occur. The charts reproduced in this guide and included as inserts are not intended for use in navigation. U.S. Coast Guard Notice to Mariners, Light Lists and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration charts should be referenced for safe navigation in any U.S. coastal waters. Convention & Visitors Bureau 3401 Cultural Center Dr // Port Arthur, TX 77642 409.985.7822 // visitportarthurtx.com ©2019 Sabine Lake Area Cruising Guide 1 CONTENTS Welcome to Fishing in Port Arthur ....................... 3 Southeast Texas Offers ‘Incredible’ Fishing ............... 4 Sabine Lake ........................................ 5 Waterway Access To Sabine Lake From The Gulf ........ 6 Intracoastal Waterway ............................. 6 Neches River .................................... 6 Sabine Lake Area Fishing Spots ........................ 7 Oyster Shell Reef ................................. 7 Tidal Movement .................................. 7 Working The Birds ................................ 8 Fishing Slicks .................................... 8 Sabine Lake Shorelines ............................ 9 Sabine Lake’s North End ........................... 9 Keith Lake .................................... -

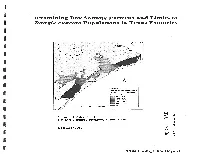

Examining Bay Salinity Patterns and Limits to Rangia Cuneata Populations in Texas Estuaries

this page left intentionally blank Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 1 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 3 3 Uncovering Key Salinity Patterns in the Guadalupe and Mission-Aransas Estuary System .. 5 3.1 Biologic Underpinnings ............................................................................ 7 3.1.1 Primary Biologic-Based Pattern Searches ................................................ 9 3.1.2 Second Tier Biologic Conditions / Limitations ........................................ 9 3.1.3 Seasonal Limits ........................................................................................ 9 3.2 Salinity in the Guadalupe and Mission-Aransas Estuary System .......... 10 3.3 Specific Salinity Searches - Computational Pathway ............................ 13 3.3.1 Primary Pattern Searches ........................................................................ 13 3.3.2 Examining Spawning Limitations .......................................................... 23 3.3.3 Return Periods ........................................................................................ 24 4 Findings ................................................................................................................................. 28 4.1 Primary Pattern Searches - Regular Consecutive Salinity Days ............ 28 4.2 Spawning Pre-Condition -

Texas Water Meetings Could Impact Toledo Bend

Texas water meetings could impact Toledo Bend Shreveport Times By Vickie Welborn . [email protected] . May 5, 2008 • Louisiana's Sabine River Authority officials will be keeping an eye on their neighbors in Texas in the coming weeks as public meetings are scheduled to solicit input on the maintenance of that state's rivers and streams. What, if anything, is ultimately decided could have an impact in Louisiana, too, since one of those waterways, the Sabine River, is shared by the adjoining states and is the source for Toledo Bend Reservoir. Of primary concern is if any change is made to the required flow of the Sabine River below the reservoir's dam. "This could impact Toledo Bend by requiring additional releases from the reservoir for downstream environmental conditions," SRA Executive Director Jim Pratt said. Doing so has the potential of undoing a long-sought agreement finally inked last year between the SRAs in Louisiana and Texas, as well as the utility companies that benefit from the reservoir's hydroelectric power plant, which requires power generation to cease once the 186,000-acre reservoir reaches 168 feet mean sea level. "Texas Parks and Wildlife has published an initial study that requires more than historical flows in the lower Sabine, and my understanding is they have determined we need to continue to release approximately 1-million acre-feet during the May to September period, which is contrary to the 168 feet minimum we have agreed to," Pratt said. Meetings Tuesday and Wednesday in Orange, Texas, will explain the technical studies and gather public knowledge and vision for the Sabine River. -

Southeast Texas & Southwest Louisiana

AUGUST - OCTOBER 2012 SOUTHEAST TEXAS & SOUTHWEST LOUISIANA Celebration Park • Groves, TX Lamar FootballBeaumont, Team • Lamar TX University Fire Museum of Texas, Downtown Beaumont Rainbow Bridge • Bridge City, TX Wesley United Methodist • Fall Pumpkin Patch Texas Star Texas Visitor Center Beaumont, TX Orange, TX Lamar Dance Team • Lamar University Beaumont, TX DOGTOBER Beaumont,FEST • Crockettt TX Street Windmill Museum Nederland, TX Viva Spotlight Marvin Atwood: Viva Vino!: Tall Tales & Short Trips: The man behind Starvin Marvin's Texas Wines The Alamo on the Gulf Coast Jim King’s Cruisin’ SETX: Plenty to do and see Loaded With Maps, Activities, Shopping & Dining In SE Texas & SW Louisiana AUGUST - OCTOBER 2012 elcome to the first edition of Viva Southeast Texas magazine, the Wmagazine dedicated to providing valuable information about our area and its surrounding neighbors. We are a local quarterly magazine published and Wednesdays distributed throughout the Southeast Karaoke Texas and Southwest Louisiana region. Viva Southeast Texas will help you “Find Your Away Around” with colorful maps, a restaurant guide, useful lists of History things to see and do, and ideas for where to shop. We will Southeast Texas...Our Origins and Roots ............................ 4 introduce you to some of the most interesting local people ON 9TH Thursdays in our “Viva Spotlight” section, and take you back in time Places of Interest with folklore and history with “Tall Tales and Short Trips.” “Buck-off” any beer Shangri-La By Cindy Yohe Lindsey........................................................... 8 If it’s entertainment and local night life you want, Listings.................................................................................................10 Viva Southeast Texas will supply you with all the latest and any burger! information from Jim “King of the Road” and our calendar Maps of events. -

TPWD Strategic Planning Regions

River Basins TPWD Brazos River Basin Brazos-Colorado Coastal Basin W o lf Cr eek Canadian River Basin R ita B l anca C r e e k e e ancar Cl ita B R Strategic Planning Colorado River Basin Colorado-Lavaca Coastal Basin Canadian River Cypress Creek Basin Regions Guadalupe River Basin Nor t h F o r k of the R e d R i ver XAmarillo Lavaca River Basin 10 Salt Fork of the Red River Lavaca-Guadalupe Coastal Basin Neches River Basin P r air i e Dog To w n F o r k of the R e d R i ver Neches-Trinity Coastal Basin ® Nueces River Basin Nor t h P e as e R i ve r Nueces-Rio Grande Coastal Basin Pease River Red River Basin White River Tongue River 6a Wi chita R iver W i chita R i ver Rio Grande River Basin Nor t h Wi chita R iver Little Wichita River South Wichita Ri ver Lubbock Trinity River Sabine River Basin X Nor t h Sulphur R i v e r Brazos River West Fork of the Trinity River San Antonio River Basin Brazos River Sulphur R i v e r South Sulphur River San Antonio-Nueces Coastal Basin 9 Clear Fork Tr Plano San Jacinto River Basin X Cypre ss Creek Garland FortWorth Irving X Sabine River in San Jacinto-Brazos Coastal Basin ity Rive X Clea r F o r k of the B r az os R i v e r XTr n X iityX RiverMesqu ite Sulphur River Basin r XX Dallas Arlington Grand Prai rie Sabine River Trinity River Basin XAbilene Paluxy River Leon River Trinity-San Jacinto Coastal Basin Chambers Creek Brazos River Attoyac Bayou XEl Paso R i c h land Cr ee k Colorado River 8 Pecan Bayou 5a Navasota River Neches River Waco Angelina River Concho River X Colorado River 7 Lampasas