Technical Guidance for Prison Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Human Factor in Prison Design: Contrasting Prison Architecture in the United States and Scandinavia

The Human Factor in Prison Design: Contrasting Prison Architecture in the United States and Scandinavia Prison design is a controversial topic in the field of architecture. The “all- seeing” Panopticon prison of the eighteenth century introduced by British social reformer Jeremy Bentham brought academic attention to the issue of prison design. Two centuries later, French philosopher and social theorist Michel Foucault used the Panopticon as a metaphor for society and its power to control beyond the physical. MEGAN FOWLER In the United States, there are two penal and prison systems -- the Pennsylvania Iowa State University System and the Auburn System. The Pennsylvania penitentiary system was influ- enced by the idea of penitence; solitude was thought to serve as punishment as well as giving time for reflection and contrition. The prison designs often recall the Panopticon with centralized configurations. The opposing system is known as the Auburn System, after the eponymous facility in New York, where impris- onment was punishment instead of a chance for reformation. It was at Auburn where the core idea of total surveillance from Bentham’s Panopticon became a reality. The Auburn system and corresponding architecture have been described as “machine-like” where prisoners are kept in tiny cells under total control. Since the 19th century, the Auburn System has predominated prison design and theory in the United States.1 In American society today some resist involving architects in creating prison facilities. “Architecture” for these buildings is discouraged.2 The environments in American prisons create opportunities for violence, tension, and hostility in inmates.3 Even employees in American prisons have been found to have a higher risk of various stress-related health issues.4 In 2013, Pelican Bay super- max prison, with its “8x10-foot, soundproof, poured-concrete cells with remote controlled doors and no windows,” provoked hunger strikes across California in solidarity for the appalling living conditions. -

Medical Care Provided in State Prisons – Study of the Costs

Medical Care Provided in State Prisons – Study of the Costs Joint Commission on Health Care October 5, 2016 Meeting Stephen Weiss Senior Health Policy Analyst 2 Study Background • By letter to the JCHC Chair, Delegate Kory requested that the Commission: ▫ Study medical care provided in State prisons Specifically, study or evaluate the costs to the state for prisoner medical care provided by the Commonwealth while inmates are incarcerated, especially costs for pharmaceutical products • The Study was approved by the JCHC members during the May 26, 2016 work plan meeting 3 Virginia Department of Corrections (VADOC) Legal Obligation to Provide Health Care to Offenders By law VADOC is required to provide adequate health care to incarcerated offenders (U.S. Const. Amend. VIII; §53.1-32, Code of Virginia). Adequate health care was defined by the United States Supreme Court beginning in 1976 (Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97, 97 S.Ct. 285). The definition encompasses the idea of providing incarcerated offenders with a “community standard” of care that includes a full range of services. The courts identified three rights to health care for incarcerated offenders: • The right to have access to care; • The right to have care that is ordered by a health care professional • The right to professional medical judgment* On July 12, 2012 a class action lawsuit was filed in federal court against VADOC over medical care at Fluvanna Correctional Center for Women. The lawsuit was settled through a Memorandum of Understanding on November 25, 2014. The settlement agreement was approved by the court in February 2016. The agreement includes the hiring of a compliance monitor and continued court supervision of the agreement. -

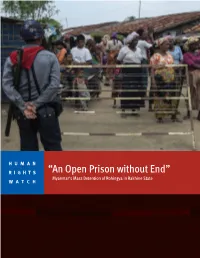

“An Open Prison Without End” WATCH Myanmar’S Mass Detention of Rohingya in Rakhine State

HUMAN RIGHTS “An Open Prison without End” WATCH Myanmar’s Mass Detention of Rohingya in Rakhine State “An Open Prison without End” Myanmar’s Mass Detention of Rohingya in Rakhine State Copyright © 2020 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-8646 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2020 ISBN: 978-1-62313-8646 “An Open Prison without End” Myanmar’s Mass Detention of Rohingya in Rakhine State Maps ................................................................................................................................ i Table .............................................................................................................................. iii Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

Continuing the Dialogue on Canada's Federal Penitentiary System

CONTINUING THE DIALOGUE ON CANADA’S FEDERAL PENITENTIARY SYSTEM A Little Less Conversation, A Lot More Action Jarrod Shook OPENING UP A CONVERSATION In our conclusion to Volume 26, Number 1&2 – Dialogue on Canada’s Federal Penitentiary System and the Need for Penal Reform – we at the Journal of Prisoners on Prisons (JPP) left off with the following hope: … that our readers, and in particular Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada Jody Wilson-Raybould who was mandated to review criminal justice, laws, policies and practices enacted during the 2006-2015 period under the previous government, will take seriously the voices of prisoners (Shook and McInnis, 2017, p. 300). To encourage this process, the 19 October 2017 launch of the JPP included a press release summarizing the recommendations for penitentiary reform made by those who participated in the dialogue. Copies of the journal (Shook et al., 2017a), the press release, along with an article summarising the project (Shook and McInnis, 2017), and information about where the journal can now be accessed online (see www.jpp.org) were also sent directly to Prime Minister Trudeau, Minister of Justice and Attorney General Jody Wilson Raybould, Minister of Public Safety Ralph Goodale, former CSC Commissioner Don Head, Members of Parliament on the Standing Committee on Public Safety & National Security, as well as the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights. These materials were also provided to members of the Senate Committee on Human Rights, the Offi ce of the Correctional Investigator, the research offi ces of CSC and Public Safety Canada’s, major media outlets, and a network of university colleagues whom we requested that they consider incorporating the special issue into their course content and required course reading lists. -

Healthcare in Prison Fact Sheet

Healthcare in Prison Prisoners should have the same access to healthcare as everyone else. This factsheet looks at what healthcare you should get if you are in prison. And at what to do if you are not getting the help you need. • You might go into prison because you have been given a prison sentence by a court. Or because you are waiting for a court hearing. This is sometimes called being ‘on remand'. • There are services that can help you while you are in prison, if you think you might need help for your mental health. • You have the same right to healthcare services as everyone else. Some prisons have a healthcare wing. You might go there if your health is very bad. • If you are too unwell to stay in prison, you could be transferred to hospital for specialist care under the Mental Health Act 1983. • Most prisons have 'Listeners'. You can talk to them if you need support. Or you can talk to the Samaritans. • There are services that can help you if you have problems with drugs or alcohol. • It is important that you get support when you are released from prison. The prison should help with this. This factsheet covers: 1. How common is mental illness in prisons? 2. What happens when I go into prison for the first time? 3. What help can I get? 4. Does the Care Programme Approach (CPA) apply in prison? 5. What other support is there for mental illness? 6. What support might I get if I use drugs or alcohol? 7. -

Financial Barriers and Utilization of Medical Services in Prison: an Examination of Co- Payments, Personal Assets, and Individual Characteristics Brian R

Journal for Evidence-based Practice in Correctional Health Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 4 November 2018 Financial Barriers and Utilization of Medical Services in Prison: An Examination of Co- payments, Personal Assets, and Individual Characteristics Brian R. Wyant PhD La Salle University, [email protected] HFoolllolyw M thi. Hs aarndne radditional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/jepch La SaPllear tU ofniv theersityC, hraiminorner@lloasgalyle C.eduommons, Health Services Research Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Dr. Brian Wyant is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at the La Salle University. He earned his PhD in criminal justice from Temple University in 2010. His publications have appeared in the Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, Justice Quarterly, Criminology, Qualitative Health Research and Social Science Research. Current and recent work has examined financial stressors for incarcerated individuals and an evaluation of the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program. Dr. Holly Harner, Ph.D., MBA, MPH, CRNP, WHCNP-BC, is currently the Associate Provost for Faculty and Academic Affairs and an Associate Professor of Public Health at La Salle University. She is a former Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Center for Health Equity Research at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. Her research interests include gender-related health disparities with a specific mpe hasis on incarcerated women. Recommended Citation Wyant, Brian R. PhD and Harner, Holly M. (2018) "Financial Barriers and Utilization of Medical Services in Prison: An Examination of Co-payments, Personal Assets, and Individual Characteristics," Journal for Evidence-based Practice in Correctional Health: Vol. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Treatment of Transgender Prisoners: What the United States Can Learn from Canada and the United Kingdom

Emory International Law Review Volume 35 Issue 1 2021 A Comparative Analysis of the Treatment of Transgender Prisoners: What the United States Can Learn from Canada and the United Kingdom Stephanie Saran Rudolph Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Recommended Citation Stephanie S. Rudolph, A Comparative Analysis of the Treatment of Transgender Prisoners: What the United States Can Learn from Canada and the United Kingdom, 35 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 95 (2021). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol35/iss1/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SARAN_1.7.21 1/7/2021 3:29 PM A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TREATMENT OF TRANSGENDER PRISONERS: WHAT THE UNITED STATES CAN LEARN FROM CANADA AND THE UNITED KINGDOM INTRODUCTION On September 29, 2015, in the early evening, 27-year-old transgender inmate Adree Edmo composes a note.1 “I do not want to die, but I am a woman and women do not have these.”2 She wants to be clear that she is not attempting suicide and leaves the note in her prison cell.3 She opens a disposable razor and boils it to disinfect it; she scrubs her hands.4 Then, “she takes the razor and slices into her right testicle with the blade.”5 This is only the first of Adree’s self- castration attempts, and while there -

Telemedicine in Corrections Cost-Effective, Safer Way to Provide Timely Healthcare to Prison Inmates

Telemedicine in Corrections Cost-effective, Safer Way to Provide Timely Healthcare to Prison Inmates Transforming Healthcare Globally™ Telemedicine in Corrections The Challenge Healthcare for inmates of federal and states prisons in the United States is costly. Healthcare and corrections are growth areas in spending and compete for stagnant 7.7 Billion state revenues. According to Bureau of Justice Statistics, $7.7 billion of an overall $38.6 billion spent on for inmate healthcare corrections in 2011 (the latest year figures are available) went for inmate healthcare. In the state of Texas, known for its “wide-open spaces,” there are 31 state prison facilities, operated by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). Although the TDCJ mission statement does not mention healthcare, a 1976 U.S. Supreme Court ruling (Estelle v. Gamble1) affirmed that all inmates are guaranteed access to basic healthcare services. The high court has long recognized that prisoners have a constitutional right to adequate health care through the Eighth Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual” punishment. In the wake of that decision, Texas set up a unique collaboration coordinated by the Correctional Managed Health Care Committee (CMHCC). This includes the TDCJ and two of the state’s leading health sciences centers: Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) and the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB). The primary purpose of this partnership is ensure that inmates at Texas prisons have access to quality healthcare while managing costs. Texas has one of the highest incarceration rates in the United States. Nearly 150,000 inmates are serving time in Texas prisons which – for the most part - are in outlying areas. -

Care and Custody in a Pennsylvania Prison

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2016 Wards Of The State: Care And Custody In A Pennsylvania Prison Nicholas Iacobelli University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Iacobelli, Nicholas, "Wards Of The State: Care And Custody In A Pennsylvania Prison" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2350. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2350 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2350 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wards Of The State: Care And Custody In A Pennsylvania Prison Abstract In this dissertation, I examine the challenges and contradictions as well as the expectations and aspirations involved in the provision of healthcare to inmates in a maximum-security prison in Pennsylvania. In 1976, the Supreme Court granted inmates a constitutional right to healthcare based on the notion that a failure to do so would constitute “cruel and unusual punishment.” Drawing on two years of ethnographic fieldwork from 2014-2016 in the prison’s medical unit with inmates, healthcare providers, and correctional staff, I demonstrate how the legal infrastructure built around this right to healthcare operates in practice and the myriad effects it has for those in state custody. Through traversing the scales of legal doctrine, privatized managed care, and collective historical memory, bringing these structural components to life in personal narratives and clinical interactions, I advance the notion that the physical space of the prison’s medical unit is a “ward of the state” – a space of care where the state itself is “made” through interactions among individuals who relay and enact the legal regulations on inmate healthcare. -

Prisons in the United States: a Need for Reform and Educational Rehabilitation

Merrimack College Merrimack ScholarWorks Social Justice Student Work Social Justice Spring 2019 Prisons in the United States: A need for reform and educational rehabilitation Amanda Alcox Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/sj_studentpub Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, and the Social Justice Commons Running Head: PRISONS IN THE UNITED STATES Prisons in the United States: A need for reform and educational rehabilitation Amanda Alcox Merrimack College SOJ 4900 Professor Mark Allman PRISONS IN THE UNITED STATES 2 Abstract: The American criminal justice system holds almost 2.3 million people in 1,719 state prisons, 102 federal prisons, 1,852 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,163 local jails, and 80 Indian Country jails as well as in military prisons, immigration detention facilities, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories. The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world. Ex-convicts express that transitioning back into society, as well as finding employers willing to hire former inmates, is a difficult task. In this capstone, we will look at prison reform from the 1800s-to-today, we will determine which roles retributive and restorative justice play in our criminal justice system, we will recognize the current implications of our current correctional system, we will engage in statistics regarding employment and homelessness rates, we will reminisce on personal experiences as an intern in a correctional facility, and lastly, we will look into programming, educational services, and professional development opportunities for inmates while serving their sentences. To understand social justice ideals, it is necessary to recognize that our nation consists of various structures, policies, and practices that either help or harm the human population. -

PUNISHMENT, PRISON and the PUBLIC AUSTRALIA the Law Book Company Ltd

THE HAMLYN LECTURES TWENTY-THIRD SERIES PUNISHMENT, PRISON AND THE PUBLIC AUSTRALIA The Law Book Company Ltd. Sydney : Melbourne : Brisbane CANADA AND U.S.A. The Carswell Company Ltd. Agincourt, Ontario INDIA N. M. Tripathi Private Ltd. Bombay ISRAEL Steimatzky's Agency Ltd. Jerusalem : Tel Aviv : Haifa MALAYSIA : SINGAPORE : BRUNEI Malayan Law Journal (Pte) Ltd. Singapore NEW ZEALAND Sweet & Maxwell (N.Z.) Ltd. Wellington PAKISTAN Pakistan Law House Karachi PUNISHMENT, PRISON AND THE PUBLIC An Assessment of Penal Reform in Twentieth Century England by an Armchair Penologist BY RUPERT CROSS, D.C.L., F.B.A. Vinerian Professor of English Law in the University of Oxford Published under the auspices of THE HAMLYN TRUST LONDON STEVENS & SONS Published in 1971 by Stevens & Sons Limited of 11 New Fetter Lane in the City of London and printed in Great Britain by The Eastern Press Ltd. of London and Reading SBN Hardback 420 43790 8 Paperback 420 43800 9 Professor Cross 1971 CONTENTS The Hamlyn Lectures ....... viii The Hamlyn Trust xi Preface xiii Introduction xv I. BACKGROUND AND DRAMATIS PERSONAE . 1 1. The Gladstone Report .... 1 2. Sir Edmund Du Cane 7 Convict Prisons ..... 7 Local Prisons ...... 9 Hard Labour 10 The Du Cane Regime . .11 Du Cane as a penologist and a person . 13 3. Sir Evelyn Ruggles-Brise . .16 Prison Conditions 17 The avoidance of imprisonment . 19 Individualisation of punishment and indeterminacy of sentence ... 22 Ruggles-Brise as a penologist and a person 27 4. Sir Alexander Paterson .... 29 Career and Personality .... 30 Paterson as a penologist.... 33 5. Sir Lionel Fox ..... -

Research Into Restorative Justice in Custodial Settings

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE IN CUSTODIAL SETTINGS Report for the Restorative Justice Working Group in Northern Ireland Marian Liebmann and Stephanie Braithwaite CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Full Report Introduction 1 Restorative Justice 1 Community Service 2 Victim/Offender Mediation 4 Victim Enquiry Work 8 Victim/Offender Groups 8 Relationships in Prison 13 Victim Awareness Work in Prisons 15 Restorative Justice Philosophy in Prisons 17 Issues in Custodial Settings 19 Conclusion 21 Recommendations 21 Useful Organisations 22 Organisations and People Contacted 25 References and useful Publications 27 Restorative Justice in Custodial Settings Marian Liebmann and Stephanie Braithwaite Executive Summary Introduction This lays out the scope of the task. As there is very little written material or research in this area, the authors of the report have, in addition to searching the literature in the normal way, made informal contact with a wide range of professionals and practitioners working in the field of Restorative Justice. The short timescale has meant that there is still material yet to arrive. Nevertheless a good range of information has been gathered. As part of this research, the authors undertook two surveys in April 1999, one of victim/offender mediation services’ involvement with offenders in custody, one of custodial institutions reported to be undertaking Restorative Justice initiatives. Restorative Justice We have used as a starting point a definition of restorative justice by the R.J.W.G. of Northern Ireland: “Using a Restorative Justice model within the Criminal Justice System is embarking on a process of settlement in which: victims are key participants, offenders must accept responsibility for their actions and members of the communities (victims and offenders) are involved in seeking a healing process which includes restitution and restoration." Community Service The Prison Phoenix Trust carried out two surveys of community work and projects carried out by prison establishments, in 1996 and 1998.