Decision About Registration of the Hibernian Hotel Site, Kowen) Notice 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kowen Cultural Precinct

April 2015 BACKGROUND INFORMATION Kowen Cultural Precinct (Blocks 16, 30, 60, 71-73, and 94, Kowen) At its meeting of 9 April 2015 the ACT Heritage Council decided that the Kowen Cultural Precinct was eligible for provisional registration. The information contained in this report was considered by the ACT Heritage Council in assessing the nomination for the Kowen Cultural Precinct against the heritage significance criteria outlined in s10 of the Heritage Act 2004. The Kowen Cultural Precinct contains several elements that make up a representation of 19th Century rural Australia that has managed to maintain its context through the formation of the Federal Capital Territory. It contains elements that show the changes in land procurement from large grants through to small selections. It contains evidence of mineral exploration, sheep farming and subsistence farming. It shows how a small community formed in the area, centred around the main property, Glenburn, with its shearing complex and nearby school. This evidence is located in the Glenburn Valley which has been largely devoid of development, allowing it to retain the integrity of the cultural landscape. Each of these elements can be seen in Figure 1 and are discussed individually below. Figure 1 Glenburn Features and pre-FCT blocks 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION – KOWEN CULTURAL PRECINCT – APRIL 2015 General Background CULTURAL LANDSCAPES The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) defines organically evolved cultural landscapes as those that have resulted ‘from an initial social, economic, administrative, and/or religious imperative and has developed its present form by association with and in response to its natural environment. -

Best Places to Take Kids Cycling

Best Places to Take Kids Cycling So, you’ve done the hard yards and taught your child to ride a bike. What now? Where can you go in Canberra to stretch their skills and show them how fun all the different types of cycling can be? Read on for Pedal Power’s top kid-friendly cycling places in Canberra. Stromlo Forest Park The redevelopment of Stromlo after the 2003 bushfires created a mecca for cycling in Canberra. The off-road facilities are world-class but for children learning to ride, you really can’t beat the tracks at the base. The purpose-built 1.3km criterium track at Stromlo Forest Park is regularly used for club races and cycling events but it’s also a perfect place for kids to practice their road-riding skills on a wide, flat, smooth surface. Check online to see if there are any bookings on the track before heading out there. Even if you can’t access the criterium track, the kids will love the always-open junior play track, complete with road markings, petrol stations, shops and a playground in the middle. Great for children up to about five, there’s also BBQ facilities. Pack a picnic lunch, let the kids ride around and around and then wander up to the viewing platform for a birds-eye view of whatever event is on. Kowen Forest When introducing children to off-road cycling, it’s best to choose single-track that’s flat and windy rather than wide fire trails that tend to have faster descents. -

Course Description – Marathon

KTR Winter Trails Marathon Course Description: Starting at the Wamboin Community Hall, you will run 2.2 km to the very end of Bingley Way and then back before turning left onto a dirt road leading up into the Native Forest. • Bingley Way is not a busy road and will not be closed to traffic for the race so please ensure you obey all road rules while running this stretch, including moving off the bitumen if a car approaches. • Runners will be required to run on the right-hand side of the road – so that they can easily see any oncoming traffic. After 0.5 km the dirt road takes a hard left turn, you will instead continue ahead up a single track. • The transition from the dirt road to the single track is particularly technical with many large and small rocks on the road’s edge. You will need to exercise caution while leaving the road. You will now run 0.8 km of single track through pristine native forest before arriving at a horse trail entrance to Kowen Forest. You will find a manned water station at this spot. • The single track is moderately technical, the major issue being the effect of dappled light masking rocks and stones on the trail. • Caution is advised on the horse trail entry gate as the poles my still be frost-covered and slippery. • A volunteer at the manned water stations will be noting down bib numbers. From the water station you will follow the fence-line for 3.2 km - on forestry trail - until you arrive at the intersection with Seven Mile Rd. -

Greenways Master Plan

Bywong/Wamboin Greenways Master Plan Version 1.1 Prepared by s.355 Greenways Management Committee Queanbeyan-Palerang Regional Council December 2018 Bywong/Wamboin Greenways Master Plan Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Principles ................................................................................................................ 4 2 Greenways Network Management ................................................................................ 4 2.1 Objectives ............................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Conditions of Use ................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Works Programs ..................................................................................................... 6 3. Greenways Management Committee ........................................................................... 6 3.1 Terms of Reference ................................................................................................ 6 3.2 Community Liaison ................................................................................................. 6 4. The Greenways Network .............................................................................................. -

Discussion Paper Updated FIN

Foreword The ACT Planning and Land Authority (ACTPLA) is the ACT Government’s statutory agency responsible for planning for the future growth of Canberra in partnership with the community. ACTPLA promotes and helps to make the Territory a well-designed, sustainable, attractive and safe urban and rural environment. One of its key functions is to ensure an adequate supply of land is available for future development, including for employment purposes. ACTPLA is seeking to identify suitable areas in east ACT for future employment development, while taking into account important environmental and other values. While employment development in much of this area is a long term initiative, it is important that planning begins early so that areas are reserved and infrastructure and services provided. This discussion paper outlines some preliminary ideas and issues for the Eastern Broadacre area, based on the ¿ndings of the ACT Eastern Broadacre Economic and Strategic Planning Direction Study (the Eastern Broadacre Planning Study). The study, including all sub-consultant reports, is released as background to this discussion paper. ACTPLA wants the community to be involved and welcomes comments on this paper. All comments received during the consultation period will be considered. A report will then be prepared for government, addressing the comments received and the recommended next steps. Community consultation will continue as planning progresses. Planning the Eastern Broadacre Area – A Discussion Paper Summary The ACT Planning and Land Authority (ACTPLA) is starting the long term planning for the eastern side of the ACT, known as the Eastern Broadacre area. This area, which extends from Majura to Hume, is identified as a future employment corridor in The Canberra Spatial Plan (2004), the ACT Government’s strategy to guide the growth of Canberra over the next 30 years and beyond. -

Glenburn Precinct (Blocks 16, 30, 60, 71–73, and 94, Kowen)

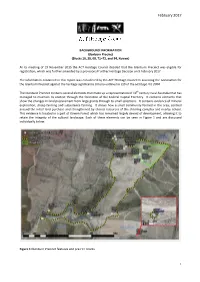

February 2017 BACKGROUND INFORMATION Glenburn Precinct (Blocks 16, 30, 60, 71–73, and 94, Kowen) At its meeting of 19 November 2015 the ACT Heritage Council decided that the Glenburn Precinct was eligible for registration, which was further amended by a provisional Further Heritage Decision on 9 February 2017. The information contained in this report was considered by the ACT Heritage Council in assessing the nomination for the Glenburn Precinct against the heritage significance criteria outlined in s10 of the Heritage Act 2004. The Glenburn Precinct contains several elements that make up a representation of 19th century rural Australia that has managed to maintain its context through the formation of the Federal Capital Territory. It contains elements that show the changes in land procurement from large grants through to small selections. It contains evidence of mineral exploration, sheep farming and subsistence farming. It shows how a small community formed in the area, centred around the initial land purchase and strengthened by shared resources of the shearing complex and nearby school. This evidence is located in a part of Kowen Forest which has remained largely devoid of development, allowing it to retain the integrity of the cultural landscape. Each of these elements can be seen in Figure 1 and are discussed individually below. Figure 1 Glenburn Precinct features and pre-FCT blocks 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION – GLENBURN PRECINCT – NOVEMBER 2015 General background CULTURAL LANDSCAPES The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) defines organically evolved cultural landscapes as those that have resulted ‘from an initial social, economic, administrative, and/or religious imperative and has developed its present form by association with and in response to its natural environment. -

The Vegetation of the Kowen, Majura and Jerrabomberra Districts of the Australian Capital Territory

THE VEGETATION OF THE KOWEN, MAJURA AND JERRABOMBERRA DISTRICTS OF THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY Prepared for: Conservation Planning and Research, ACT Government Authors: Greg Baines, Murray Webster, Emma Cook, Luke Johnston and Julian Seddon Technical Report 28 November 2013 Conservation Planning and Research | Policy Division | Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate Technical Report 28 The Vegetation of the Kowen, Majura and Jerrabomberra Districts of the Australian Capital Territory Greg Baines, Murray Webster, Emma Cook, Luke Johnston and Julian Seddon Conservation Planning and Research Policy Division Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate GPO Box 158, CANBERRA ACT 2601 November 2013 2 1 Acknowledgements The authors wish to thank Ken Turner (NSW Office of Environment and Heritage) for his detailed review of this document, Robert Armstrong for his assistance and advice on mapping methods and community classification, Stephen Skinner (ACT Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate) for his assistance in identifying aquatic communities and the ACT Economic Development Directorate for funding this project. © Australian Capital Territory, Canberra 2013 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without the written permission from the ACT Government, Conservation Research Unit, Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate, GPO Box 158 Canberra ACT 2601. ISBN 978-0-9871175-6-4 Published by the Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate, ACT Government Website: www.environment.act.gov.au This publication should be cited as: Baines G, Webster M, Cook E, Johnston L, and Seddon J, 2013, ‘The vegetation of the Kowen, Majura and Jerrabomberra districts of the ACT’, Technical Report 28, Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate, ACT Government 3 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ -

B-Hazzard-Letter.Pdf

Canberra Airport N60 Contours Jerrabomberra Hume Tralee Legend N60 contours - Practical Ultimate Capacity 10-20 events/day 20-50 events/day 50-100 events/day 100-200 events/day 200+ events/day South Tralee general residential area ACT Border 0 400 800 1,600 Meters 23/07/2013 Canberra Airport N60 Contours SUTTON GUNGAHLIN EAGLE HAWK BELCONNEN MITCHELL NORTH CANBERRA WAMBOIN CANBERRA CITY STROMLO SOUTH CANBERRA KOWEN FOREST WESTON CREEK WODEN VALLEY QUEANBEYAN CARWOOLA JERRABOMBERRA TUGGERANONG GOOGONG DAM GOOGONG ROYALLA THARWA Legend N60 contours - Practical Ultimate Capacity 10-20 events/day 20-50 events/day 50-100 events/day 100+ events/day Suburb boundary Road network ACT Border 0 4,000 8,000 16,000 Meters 23/07/2013 Canberra Airport N65 Contours Jerrabomberra Hume Tralee Legend N65 contours - Practical Ultimate Capacity 10-20 events/day 20-50 events/day 50-100 events/day 100-200 events/day 200+ events/day South Tralee general residential area ACT Border 0 400 800 1,600 Meters 23/07/2013 Canberra Airport N65 Contours SUTTON GUNGAHLIN EAGLE HAWK BELCONNEN MITCHELL NORTH CANBERRA WAMBOIN CANBERRA CITY STROMLO SOUTH CANBERRA KOWEN FOREST WESTON CREEK WODEN VALLEY QUEANBEYAN CARWOOLA JERRABOMBERRA TUGGERANONG GOOGONG DAM GOOGONG ROYALLA THARWA Legend N65 contours - Practical Ultimate Capacity 10-20 events/day 20-50 events/day 50-100 events/day 100+ events/day Suburb boundary Road network ACT Border 0 4,000 8,000 16,000 Meters 23/07/2013 Canberra Airport N70 Contours Jerrabomberra Hume Tralee Legend N70 contours - Practical Ultimate Capacity -

ACT Electorate Map: Canberra

SEAT OF CANBERRA Top Five Canberra priorities? 1. Global warming and climate change (1 in 2 people agree) 2. Improving education (1 in 3 people agree) 3. Open and honest government (1 in 3 people agree) 4. Improving health services and hospitals (1 in 3 people agree) 5. Keeping day to day living costs down (1 in 4 people agree) WHAT TO DO? These are the top priorities for the seat of Canberra identified from a survey of 125,000 voters by the Australian Futures Foundation (with Roy Morgan Research ). In your groups you might want to discuss whether these align with your priorities with candidates and what you’d like done about them. If you agree, disagree or identify other specific Canberra priorities please write them down and place these on this map using your sticky notes. We’ll collect, collate and include this information in our summary from today which will be made public and also help shape our advice to the next member for Canberra. See https://theperfectcandidate.org.au/about for more Which suburbs are in Canberra? information on ‘The Perfect Candidate’. Acton, Ainslie, Aranda, Barton, Beard, Belconnen District, Braddon, Bruce, Campbell, Canberra Airport, Canberra Central, Canberra City, Cook, Curtin, Deakin, Dickson, Downer, Forrest, Fyshwick, Garran, Giralang, Griffith, Hackett, Hawker, Hughes, Kaleen, Kingston, Kowen District, Kowen Forest, Lawson, Lyneham, Lyons , Macquarie, Majura District, Molonglo Valley District, Narrabundah, Oaks Estate, O'connor, Parkes, Pialligo, Red Hill, Reid, Symonston, Turner, Watson, Weetangera, Weston Creek District, Yarralumla CANBERRA FACTS POVERTY HOUSING STRESS SPOTLIGHT Canberra has the second highest poverty rate of all There are 7.1% of people in housing stress in the The division of Canberra is the ACT seat with the three divisions at 8.9% and the highest child poverty seat of Canberra with 9.7% of children in housing highest number of rented households rate at 13.9%. -

Australian Capital Territory.Pdf

AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY, Statistical Divisions—2004 Hall Lake Ginninderra LakeLakeLake BurleyBurleyBurley GriffinGriffin Cotter Dam 0505 CanberraCanberra CanberraCanberra QueanbeyanQueanbeyanQueanbeyan Lake Tuggeranong Bendora Dam Tharwa Corin Dam WilliamsdaleWilliamsdale 1010 AustralianAustralian CapitalCapital TerritoryTerritory -- BalBal 0 10 Kilometres ABS • AUSTRALIAN STANDARD GEOGRAPHICAL CLASSIFICATION • 1216.0 • 2004 197 AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY, Statistical Subdivisions and Statistical Local Areas—2004 05400540 Gungahlin-HallGungahlin-Hall Gungahlin-Hall - SSD Bal 05100510 BelconnenBelconnen 05050505 NorthNorth CanberraCanberra Belconnen - SSD Bal Stromlo Majura SeeSee EnlargementEnlargement Kowen 05350535 05200520 05150515 SouthSouth WestonWeston Creek-StromloCreek-Stromlo WodenWoden CanberraCanberra ValleyValleyValley 10051005 Tuggeranong - 05250525 SSD Bal AustralianAustralian CapitalCapital TerritoryTerritory -- BalBal TuggeranongTuggeranong Remainder of ACT Statistical Local Area Kowen 0505 Statistical Subdivision North Canberra 0 20 Kilometres 198 ABS • AUSTRALIAN STANDARD GEOGRAPHICAL CLASSIFICATION • 1216.0 • 2004 AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY, Statistical Subdivisions and Statistical Local Areas: Enlargement—2004 Hall Amaroo Ngunnawal (Belconnen - SSD Bal) Nicholls Gungahlin-Hall - SSD Bal Fraser Dunlop Palmerston Spence 05400540 Charnwood 05400540 Gungahlin-HallGungahlin-Hall Flynn Melba Macgregor Evatt Giralang Latham Mitchell Holt Florey McKellar Kaleen Higgins Scullin Watson Page Lyneham Belconnen 05100510 -

Act Government

A SUBMISSION FROM THE ACT GOVERNMENT TO THE INQUIRY OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE NATIONAL CAPITAL AND EXTERNAL TERRITORIES INTO THE ROLE OF THE NATIONAL CAPITAL AUTHORITY JUNE 2003 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................III Strategic Outcomes ................................................................................................................... iii Specific Recommendations: .......................................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION........................................................................................... 1 EARLY SIGNS OF CONCERN................................................................................................. 1 STATE–LEVEL PLANNING RIGHTS FOR THE PEOPLE OF THE ACT ....................................... 2 A PLAN FOR THE TIMES ...................................................................................................... 3 THE WAY FORWARD........................................................................................................... 4 TOR 1: THE ROLE OF THE NATIONAL CAPITAL AUTHORITY AS OUTLINED IN THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY (PLANNING AND LAND MANAGEMENT) ACT 1988........................... 5 LACK OF CLARITY IN PLANNING RESPONSIBILITIES............................................................ 6 URBAN CAPABLE LAND ...................................................................................................... 6 COMMONWEALTH EMPLOYMENT AND THE REVITALISATION -

The Glenburn and Burbong Historic Precinct in the Kowen Forest, Act: More Recent Information About Some of the Sites and the People

THE GLENBURN AND BURBONG HISTORIC PRECINCT IN THE KOWEN FOREST, ACT: MORE RECENT INFORMATION ABOUT SOME OF THE SITES AND THE PEOPLE Colin McAlister, November 2013 My monograph, Twelve historic sites in the Glenburn and Burbong areas of the Kowen Forest, Australian Capital Territory, published by the Na6onal Parks Associa6on of the ACT in November 2007 needs some upda6ng and correc6ng. (The monograph is available on the NPA’s website www.npaact.org.au under Publica6ons, Out of Print Publica6ons.) Since 2008 The Parks and Conserva6on Service and the Friends of Glenburn have undertaken substan6al protec6on and conserva6on of some of the sites. These ac6ons are included in my July 2013 ‘Work in Progress’ ar6cle on the same website www.npaact.org.au under Our Friends, Friends of Glenburn. The purpose of this ar6cle is to set out recent informa6on that has come to light from various sources about the sites and the people associated with them and also to make some minor correc6ons to the material in my 2007 monograph. The page references are generally to my 2007 monograph. Ideally, I should prepare a second edi6on of my 2007 monograph. But I simply do not have the inclina6on or the stamina at present. So you will have to bear with me in dealing with essen6ally new informa6on and/or interpreta6ons about some of the sites and the people associated with them. Unfortunately, in some areas, I have raised ques6ons than I have not been able to answer. I suggest that you have a copy of my 2007 monograph close by when you read this ar6cle.