Exploring Children's Work Involvement an D School Atten Dance in Rural Cambodia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SECURING INDIVIDUALS in THEIR RIGHTS Unit 2, Lesson 1 UNIT 2, LESSON 1 SECURING INDIVIDUALS in THEIR RIGHTS

The Freedom Collection Presents: SECURING INDIVIDUALS IN THEIR RIGHTS Unit 2, Lesson 1 UNIT 2, LESSON 1 SECURING INDIVIDUALS IN THEIR RIGHTS INTRODUCTION In this lesson, students will review their understanding of the sources and characteristics of freedom and how governments secure individual rights. They will watch video testimonies from the Freedom Collection to explore how contemporary political dissidents from different countries and cultures explain their understanding of rights and express their expectations of government in respecting them. Students will examine how the United States Constitution and its Amendments secure individual rights and use an established methodology to rate the actual experience of freedom in the United States today. In doing so, students will understand that a “liberal democracy” describes a country in which the most substantial range of political, economic, and personal rights are secured in practice under a limited, representative system of government. GUIDING QUESTIONS ⋅ How do the U.S. Constitution and its Amendments secure individual political, economic, and personal rights for Americans? ⋅ What makes the United States a liberal democracy today, with respect to the individual’s experience of rights and freedoms under a limited, representative system of government? ⋅ How do contemporary political dissidents living under authoritarian systems of government understand their rights? What are their expectations of government in securing rights? OBJECTIVES STUDENTS WILL: ⋅ Understand how the U.S. Constitution and its Amendments secure individual rights for Americans. ⋅ Analyze what makes the United States a liberal democracy today, with respect to the individual’s experience of rights and freedoms under a limited, representative system of government. -

Applying Library Values to Emerging Technology Decision-Making in the Age of Open Access, Maker Spaces, and the Ever-Changing Library

ACRL Publications in Librarianship No. 72 Applying Library Values to Emerging Technology Decision-Making in the Age of Open Access, Maker Spaces, and the Ever-Changing Library Editors Peter D. Fernandez and Kelly Tilton Association of College and Research Libraries A division of the American Library Association Chicago, Illinois 2018 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of Ameri- can National Standard for Information Sciences–Permanence of Paper for Print- ed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. ∞ Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the Library of Congress. Copyright ©2018 by the Association of College and Research Libraries. All rights reserved except those which may be granted by Sections 107 and 108 of the Copyright Revision Act of 1976. Printed in the United States of America. 22 21 20 19 18 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................ix Peter Fernandez, Head, LRE Liaison Programs, University of Tennessee Libraries Kelly Tilton, Information Literacy Instruction Librarian, University of Tennessee Libraries Part I Contemplating Library Values Chapter 1. ..........................................................................................................1 The New Technocracy: Positioning Librarianship’s Core Values in Relationship to Technology Is a Much Taller Order Than We Think John Buschman, Dean of University Libraries, Seton Hall University Chapter 2. ........................................................................................................27 -

2012 ANNUAL REPORT | 2 GEORGE W.GEORGE BUSH W.PRESIDENTIAL BUSH PRESIDENTIAL CENTER CENTER — 2012 — 2012 ANNUAL ANNUAL REPORT REPORT || 11 Building Momentum

BUILDING MOMENTUM DELIVERING RESULTS 2O12 ANNUAL REPORT ThaNk you fOr your sUppOrT Of ThE George W. BUsh prEsidentiaL Center. WE arE Grateful ThaT your generOsity has helped Bring ThIs institution to lifE — and ThaT togethEr we CaN MakE a diffErence fOr generations to come. GEORGE W. BUSH PRESIDENTIAL CENTER — 2012 ANNUAL REPORT | 2 GEORGE W.GEORGE BUSH W.PRESIDENTIAL BUSH PRESIDENTIAL CENTER CENTER — 2012 — 2012 ANNUAL ANNUAL REPORT REPORT || 11 Building Momentum The George W. Bush Presidential Center experienced tremendous growth in 2012. One of the most visible signs was the construction of our beautiful, new, state-of-the-art facility on the campus of Southern Methodist University. We are pleased to report that the building and surrounding grounds were completed on budget and on time. In the fall, the National Archives and Records Administration began moving the extensive collection of documents and artifacts representing President Bush’s two terms in office into their permanent home at the Bush Center. At the Bush Institute, our programs in economic growth, education reform, global health and human freedom grew significantly in both number and influence. The Bush Institute published its first book— The 4% Solution—which became an Amazon best-seller, and also inaugurated an annual high school Economic Debate weekend that encourages young people to think critically about economic issues. The Alliance to Reform Education Leadership expanded its nationwide network from 19 to 28 programs. Each of these programs is working to better prepare and support school principals to improve student achievement. The Military Service Initiative began a focused effort to help nonprofit organizations better assist our brave military men and women and their families. -

Documentation of Sexual Violence Against Rohingya Women and Girls in Myanmar

(Re)Imagining ‘Justice’: Documentation of Sexual Violence against Rohingya Women and Girls in Myanmar by Theressa Etmanski Master of Arts, University of British Columbia, 2012 Juris Doctor, University of British Columbia, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Simon Fraser University, 2008 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF LAW in the Faculty of Law Theressa Etmanski, 2018 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee (Re)Imagining ‘Justice’: Documentation of Sexual Violence against Rohingya Women and Girls in Myanmar by Theressa Etmanski Master of Arts, University of British Columbia, 2012 Juris Doctor, University of British Columbia, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Simon Fraser University, 2008 Supervisory Committee Victor V. Ramraj, Department of Law Supervisor Helen Lansdowne, Centre for Asia-Pacific Initiatives Outside Member iii Abstract The Rohingya population of Myanmar have been called one of the most persecuted ethnic minorities on earth. Beyond the systemic discrimination and ongoing violations of basic human rights, Tatmadaw operations against Rohingya communities in Rakhine State in recent years have amounted to ethnic cleansing, if not genocide. Reports of widespread sexual violence by security forces have garnered significant international attention, increasing our collective awareness of how rape is used as a weapon of war. In light of Canada’s Special Envoy to Myanmar’s report recommending that investigation take place to establish an evidence base for future prosecutions, it is critical that sexual and gender-based violence crimes be adequately factored into documentation strategies. -

George W. Bush Presidential Center 2011 Annual Report

GEORGE W. BUSH PRESIDENTIAL CENTER 2011 ANNUAL REPORT “This center will be the focus of our attention, the place where we pursue our passions and the forum for our public service for as long as we live.” President George W. Bush Dallas, Texas November 12, 2009 Thank you for supporting the George W. Bush Presidential Center at Southern Methodist University. We are proud to have you as a partner in this important project. For generations to come, the Bush Center will work to develop practical, principled solutions that have a meaningful influence on the global challenges we face. The Bush Center will advance our lifelong commitment to a freer and better world. At the Bush Institute, we honor the timeless truth, “to whom much is given, much is required.” With your support, we have extended the reach of freedom by promoting human rights for women in Afghanistan and Egypt; political dissidents in places like Cuba, Iran and Venezuela; and victims of religious persecution in China. Your investment is helping save lives by expanding cervical and breast cancer programs in sub-Saharan Africa. Here at home, you are helping ensure that American students have the knowledge needed to succeed in school and in life. Your contribution is helping promote free markets and economic growth so America will remain the home of the most industrious, enterprising and productive people in the world. Every project we undertake is designed to make an impact in the real world. We set goals and measure results. We place great value in the power of ideas and actions, and leading scholars and experts fuel our efforts. -

Collected Writings from the International Christian Concern Fellows Program

THE INTERNAtiONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REVIEW Collected Writings from the International Christian Concern Fellows Program VOLUME 1 NO. 1 SUMMER 2020 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM COLLECTED WRITINGS FROM THE INTERNATIONAL CHRISTIAN CONCERN FELLOWS PROGRAM On the cover: Raveed, a young Kashmiri Christian, lifts his hands in prayer to Jesus in the afternoon sun on Kashmir’s Dal Lake. The Kashmir region has seen sigificant religious oppression in recent years. Credit: ICC Fellow John Fredricks International Christian Concern P. O. Box 8056 Silver Spring, MD 20907 Copyright © 2020 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Dear Reader, In 2019, International Christian Concern launched an initiative aimed at gathering the leading experts, professionals, and advocates focused on international religious freedom and pooling their expertise to help highlight the global issue of religious persecution. ICC’s fellows have written, researched, and wrestled with this topic and other related themes throughout 2019 and into 2020. This cohort of fellows has pushed the envelope, enlightened the discussion, and advocated for coherent government involvement on this largely-ignored issue. The credit for these writings belongs to them. This is the inaugural publication of the International Christian Concern Fellows Program, and we are proud to share some of our Fellows’ best pieces in this first-ever publication of the Journal on International Religious Freedom: Collection of Writings from the International Christian Concern Fellows Program. Sincerely, Matias Perttula Advocacy Director International Christian Concern i TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Editor i Policy International Christian Concern Fellows Brief: 1 Religious Freedom as an Essential Tool of Statecraft ICC Fellows Brief Selected transcript from a meeting hosted by ICC in late January 2020 to discuss the role of religious freedom in U.S. -

WHAT IS FREEDOM? Unit 1, Lesson 1 UNIT 1, LESSON 1 WHAT IS FREEDOM?

The Freedom Collection Presents: WHAT IS FREEDOM? Unit 1, Lesson 1 UNIT 1, LESSON 1 WHAT IS FREEDOM? INTRODUCTION This lesson will explore the nature and experience of freedom. Students will examine the ideas of great thinkers of the past who have written about the sources and characteristics of freedom. They will also examine the actual experiences of contemporary political dissidents who have struggled to achieve freedom from tyranny. Students will develop definitions of freedom and tyranny that they can substantiate with analysis, explanations, and facts. GUIDING QUESTIONS ⋅ How have people defined the sources of freedom and its essential characteristics throughout history? ⋅ What are the characteristics of tyranny? ⋅ Why do people seek freedom from tyranny? OBJECTIVES STUDENTS WILL: ⋅ Analyze ideas about, and compare actual experiences of, freedom and tyranny. ⋅ Engage in conversations about freedom and tyranny. ⋅ Develop definitions of freedom and tyranny, making use of ideas expressed by prominent thinkers of the past and the experiences of today’s political dissidents. LENGTH OF LESSON ⋅ Day 1—55 minutes ⋅ Day 2—50 minutes CURRICULUM STANDARDS TEKS ⋅ WH. 20.C “Explain the political philosophies of individuals such as John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, Voltaire, Charles de Montesquieu, Jean Jacques Rousseau, Thomas Aquinas, John Calvin, Thomas Jefferson, and William Blackstone.” 2 ⋅ WH.21A “Describe how people have participated in supporting or changing their government.” ⋅ WH.21B “Describe the rights and responsibilities of citizens and -

Review 4-13 Online.Indd

THE MISSOURI CONFERENCE REVIEW an edition of the United Methodist Reporter Leading congregations to lead people to actively follow Jesus Christ On Tour Charred Offerings l Fire damages 024000 Volume 158 Bob Farr shares Annual Conference Number 50 l April 13, 2012 about his interview North Park UMC offerings help people experience. 4A in Holy Week. 5A near and far. 6A Two Sections, Section A Fathers and daughters enjoy a dance at St. James UMC. New role Rev. Cody Collier (center), head of the Missouri Conference UMM has strength, Baker named direc- delegation, and Brian Hammons listen to Elijah Stansell tor of Mission, Service answer questions during the episcopal candidate interview purpose at St. James and Justice Ministries process. Getting men to commit to support and vitality to be as come to church on Sunday morn- active as it is. Jeffery Baker has been named Delegation reviews ing can be challenging. So how “The heritage of the men who as the next Missouri Conference about getting them to come to a have been with us a long time is Director of Mission, Service and Episcopal candidates service that starts at 6 a.m.? And very important to us,” Ngomsi Justice Ministries. Baker will let’s make it on New Year’s Day. said. replace Rev. Max Marble when he The Missouri Conference by delegates what her greatest That’s the kind of challenge that But the group is also aware retires after Annual Conference Delegation joined the Kansas gifts are that she would bring to the United Methodist Men at St. -

CASE STUDIES of FREEDOM in the TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY Unit 4, Lesson 2 UNIT 4, LESSON 2 CASE STUDIES of FREEDOM in the TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

The Freedom Collection Presents: CASE STUDIES OF FREEDOM IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY Unit 4, Lesson 2 UNIT 4, LESSON 2 CASE STUDIES OF FREEDOM IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY INTRODUCTION This multi-day lesson invites students to analyze contemporary efforts to achieve freedom and democracy in Burma (also known as Myanmar), China, Cuba, and Tunisia. Students will be divided into groups and research one of the four countries using case studies provided with the lesson, oral histories found in the Freedom Collection, and analysis from the nonprofit organization Freedom House. Each group will use its research to prepare a mock newscast and present it to the class. GUIDING QUESTIONS ⋅ How can we understand the importance of freedom by studying contemporary struggles for democratic government and individual rights? ⋅ How successful have movements for democratic government and individual rights been in the case studies provided in this lesson? ⋅ How have external factors contributed to progress or setbacks in the case studies provided in this lesson? OBJECTIVES STUDENTS WILL: ⋅ Research and analyze contemporary movements for freedom in Burma, China, Cuba, and Tunisia. ⋅ Explore the role of individuals in advocating for democratic government and individual rights in each example. ⋅ Consider the role of external factors in movements for democratic government and individual rights. ⋅ Work cooperatively in a group to teach fellow classmates about one of the four case studies using a mock newscast. 2 LENGTH OF LESSON ⋅ Day 1—55 minutes ⋅ Day 2—55 minutes -

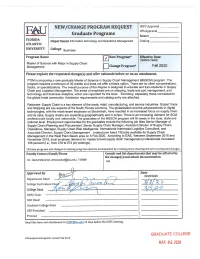

Master of Science with Major in Supply Chain Management

Master of Science with Major in Supply Chain Management The Master of Science in Supply Chain Management provides a strong curriculum, delivering the foundations and principles of Supply Chain Management, Operations Management, Procurement, and Sourcing, integrated with concentrated study of Business Analytics, Shipping and Trade in order to provide graduates with the key skills and hands-on experience demanded by employers locally, statewide, nationally, and internationally. Students are required to complete 30 graduate-level credits with a 3.0 GPA or better to graduate. The program does not offer a thesis option. Admissions The College of Business seeks a diverse, highly-qualified group of graduate students. Applications are evaluated on several factors emphasizing prior academic performance, GMAT or GRE scores, work experience, and the potential for scholarly and professional success. • Bachelor’s degree in any discipline; no business prerequisites are required • GPA approximately 3.0 or higher over the last 60 undergraduate credits • Two or more years of non-industry-specific professional work experience • GMAT/GRE - A combined score (verbal + quantitative) of at least 295 on the Graduate Record Examination (GRE) or a GMAT score of 500 or higher. GRE scores more than five years old are normally not acceptable • International students from non-English-speaking countries must be proficient in written and spoken English as evidenced by a score of at least 500 (paper-based test) or 213 (computer-based test) or 79 (Internet-based test) on the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) or a score of at least 6.0 on the International English Language Testing System (IELTS); and • Meet other requirements of the FAU Graduate College Degree Requirements Students are required to complete 30 graduate-level credits, or 10 three-credit courses (5000 level or higher), with a 3.0 GPA or higher to graduate. -

Fuel on the Fire: the Case Against Arming Nonstate Actors in Intrastate Conflicts Hall, Thomas C 28 November 2017

Fuel on the Fire: The Case Against Arming Nonstate Actors in Intrastate Conflicts Hall, Thomas C 28 November 2017 Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Dr. Carolyn Stephenson for her consistent assistance and encouragement throughout the process of writing this thesis, and Dr. Colin Moore for standing on my thesis committee. A special thanks also to Dr. Vernadette Gonzalez for the her understanding and accommodation of my rather atypical circumstances and timeline as I wrote this thesis. Table of Contents Introduction and Significance …………………………………………………………………………………...1 Literature Review……………………………………………………..............................................................6 Databases Utilized for Quantitative Research………………………………………………………………...17 Methodology……………………………………………………………………………………………………….25 Dataset 1: Violence, Fragility, Military and Diplomatic Support in Intrastate Conflicts…………………….35 Dataset 1: Understanding the Data and Sources …………………………………………………………….36 Analyzing the Data in Dataset 1…………………………………………………………………………………51 Selecting Case Studies…………………………………………………………………………………………..56 Case Study on Egypt...…………………………………………………………………………………………...58 Case Study on Syria..………………………………………………...............................................................65 Case Study on Ukraine..……………………………………………..............................................................72 Findings of the Study…………………………...………………………………………………………………...88 Questions for Further Study……………………………………...……………………………………………….91 Conclusion - Policy Implications………………………………………………………………………………….93