National Report on Sustainable Forests – 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella Species

A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Synopsis Fungorum 8 Fungiflora - Oslo - Norway A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Printed in Eko-trykk A/S, Førde, Norway Printing date: 1. August 1995 ISBN 82-90724-14-4 ISSN 0802-4966 A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Synopsis Fungorum 8 Fungiflora - Oslo - Norway 6 Authors address: Center for Forest Mycology Research Forest Products Laboratory United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service One Gifford Pinchot Dr. Madison, WI 53705 USA ABSTRACT Once a taxonomic refugium for nearly any white-spored agaric with an annulus and attached gills, the concept of the genus Armillaria has been clarified with the neotypification of Armillaria mellea (Vahl:Fr.) Kummer and its acceptance as type species of Armillaria (Fr.:Fr.) Staude. Due to recognition of different type species over the years and an extremely variable generic concept, at least 274 species and varieties have been placed in Armillaria (or in Armillariella Karst., its obligate synonym). Only about forty species belong in the genus Armillaria sensu stricto, while the rest can be placed in forty-three other modem genera. This study is based on original descriptions in the literature, as well as studies of type specimens and generic and species concepts by other authors. This publication consists of an alphabetical listing of all epithets used in Armillaria or Armillariella, with their basionyms, currently accepted names, and other obligate and facultative synonyms. -

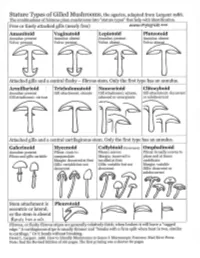

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

Taxonomy, Ecology and Distribution of Melanoleuca Strictipes (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) in Europe

CZECH MYCOLOGY 69(1): 15–30, MAY 9, 2017 (ONLINE VERSION, ISSN 1805-1421) Taxonomy, ecology and distribution of Melanoleuca strictipes (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) in Europe 1 2 3 4 ONDREJ ĎURIŠKA ,VLADIMÍR ANTONÍN ,ROBERTO PARA ,MICHAL TOMŠOVSKÝ , 5 SOŇA JANČOVIČOVÁ 1 Comenius University in Bratislava, Faculty of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmacognosy and Botany, Kalinčiakova 8, SK-832 32 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] 2 Department of Botany, Moravian Museum, Zelný trh 6, CZ-659 37 Brno, Czech Republic; [email protected] 3 Via Martiri di via Fani 22, I-61024 Mombaroccio, Italy; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology, Mendel University in Brno, Zemědělská 3, CZ-613 00 Brno, Czech Republic; [email protected] 5 Comenius University in Bratislava, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Department of Botany, Révová 39, SK-811 02 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] Ďuriška O., Antonín V., Para R., Tomšovský M., Jančovičová S. (2017): Taxonomy, ecology and distribution of Melanoleuca strictipes (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) in Europe. – Czech Mycol. 69(1): 15–30. Melanoleuca strictipes (P. Karst.) Métrod, a species characterised by whitish colours and macrocystidia in the hymenium, has for years been identified as several different species. Based on morphological studies of 61 specimens from eight countries and a phylogenetic analysis of ITS se- quences, including type material of M. subalpina and M. substrictipes var. sarcophyllum, we confirm conspecificity of these specimens and their identity as M. strictipes. The lectotype of this species is designated here. The morphological and ecological characteristics of this species are presented. Key words: taxonomy, phylogeny, M. -

Newsletter of Jun

V OMPHALINISSN 1925-1858 Vol. V, No 6 Newsletter of Jun. 21, 2014 OMPHALINA OMPHALINA, newsletter of Foray Newfoundland & Labrador, has no fi xed schedule of publication, and no promise to appear again. Its primary purpose is to serve as a conduit of information to registrants of the upcoming foray and secondarily as a communications tool with members. Issues of OMPHALINA are archived in: is an amateur, volunteer-run, community, Library and Archives Canada’s Electronic Collection <http://epe. not-for-profi t organization with a mission to lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/300/omphalina/index.html>, and organize enjoyable and informative amateur Centre for Newfoundland Studies, Queen Elizabeth II Library mushroom forays in Newfoundland and (printed copy also archived) <http://collections.mun.ca/cdm4/ description.php?phpReturn=typeListing.php&id=162>. Labrador and disseminate the knowledge gained. The content is neither discussed nor approved by the Board of Directors. Therefore, opinions expressed do not represent the views of the Board, Webpage: www.nlmushrooms.ca the Corporation, the partners, the sponsors, or the members. Opinions are solely those of the authors and uncredited opinions solely those of the Editor. ADDRESS Foray Newfoundland & Labrador Please address comments, complaints, contributions to the self-appointed Editor, Andrus Voitk: 21 Pond Rd. Rocky Harbour NL seened AT gmail DOT com, A0K 4N0 CANADA … who eagerly invites contributions to OMPHALINA, dealing with any aspect even remotely related to mushrooms. E-mail: info AT nlmushrooms DOT ca Authors are guaranteed instant fame—fortune to follow. Authors retain copyright to all published material, and BOARD OF DIRECTORS CONSULTANTS submission indicates permission to publish, subject to the usual editorial decisions. -

Toxic Fungi of Western North America

Toxic Fungi of Western North America by Thomas J. Duffy, MD Published by MykoWeb (www.mykoweb.com) March, 2008 (Web) August, 2008 (PDF) 2 Toxic Fungi of Western North America Copyright © 2008 by Thomas J. Duffy & Michael G. Wood Toxic Fungi of Western North America 3 Contents Introductory Material ........................................................................................... 7 Dedication ............................................................................................................... 7 Preface .................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 7 An Introduction to Mushrooms & Mushroom Poisoning .............................. 9 Introduction and collection of specimens .............................................................. 9 General overview of mushroom poisonings ......................................................... 10 Ecology and general anatomy of fungi ................................................................ 11 Description and habitat of Amanita phalloides and Amanita ocreata .............. 14 History of Amanita ocreata and Amanita phalloides in the West ..................... 18 The classical history of Amanita phalloides and related species ....................... 20 Mushroom poisoning case registry ...................................................................... 21 “Look-Alike” mushrooms ..................................................................................... -

2 the Numbers Behind Mushroom Biodiversity

15 2 The Numbers Behind Mushroom Biodiversity Anabela Martins Polytechnic Institute of Bragança, School of Agriculture (IPB-ESA), Portugal 2.1 Origin and Diversity of Fungi Fungi are difficult to preserve and fossilize and due to the poor preservation of most fungal structures, it has been difficult to interpret the fossil record of fungi. Hyphae, the vegetative bodies of fungi, bear few distinctive morphological characteristicss, and organisms as diverse as cyanobacteria, eukaryotic algal groups, and oomycetes can easily be mistaken for them (Taylor & Taylor 1993). Fossils provide minimum ages for divergences and genetic lineages can be much older than even the oldest fossil representative found. According to Berbee and Taylor (2010), molecular clocks (conversion of molecular changes into geological time) calibrated by fossils are the only available tools to estimate timing of evolutionary events in fossil‐poor groups, such as fungi. The arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiotic fungi from the division Glomeromycota, gen- erally accepted as the phylogenetic sister clade to the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, have left the most ancient fossils in the Rhynie Chert of Aberdeenshire in the north of Scotland (400 million years old). The Glomeromycota and several other fungi have been found associated with the preserved tissues of early vascular plants (Taylor et al. 2004a). Fossil spores from these shallow marine sediments from the Ordovician that closely resemble Glomeromycota spores and finely branched hyphae arbuscules within plant cells were clearly preserved in cells of stems of a 400 Ma primitive land plant, Aglaophyton, from Rhynie chert 455–460 Ma in age (Redecker et al. 2000; Remy et al. 1994) and from roots from the Triassic (250–199 Ma) (Berbee & Taylor 2010; Stubblefield et al. -

The Tricholoma Caligatum Group in Europe and North Africa

Karstenia 28:65-77. 1988 (1989) The Tricholoma caligatum group in Europe and North Africa ILKKA KYTOVUORI KYTOVUORI, I. 1989: The Tricholoma caligaturn group in Europe and North Africa. - Karstenia 28:65-77. Three species are recognized in the Tricholoma caligatum group in Europe: T. caligatum (Viv.) Ricken, T. nauseosum (Blytt) Kytiiv., comb. nova, and T. dulciolens Kytov., spec. nova. The first two species are also reported from North Africa. The East Asian T. matsutake (S. Ito & Imai) Singer is included in T. nauseosum, which is thus an edible fungus of major international interest. The distribution of each species in the study area is mapped, and their ecology and relationships are discussed. llkka Kytovuori, Department of Botany, University of Helsinki, Unioninkatu 44, SF-00170 Helsinki, Finland In Europe (e.g. Moser 1983) the Tricholoma caliga rium of Soc. Catal. Micol. Barcelona. Types and tum group is traditionally supposed to be represented some other specimens were also examined from by one species only. One species is also recognized MICH. in East Asia, whereas in North America Smith (1979) Microscopical characters were examined with the reports four species and four varieties of the group. microscope Leiz Laborlux 12 at magnifications of However, heterogeneity is evident in the group in about 625 and 1 560. Spores, basidia and surface hy Europe as well, though to a smaller extent than in phae were drawn with the Leiz drawing tube at a North America. Smith (1979) and most other North magnification of 2 OOO. Spores were examined, mea American authors, e.g. Pomerleau (1980), refer the sured (with an ocular micrometer) and drawn from T. -

(Agaricales) in New Zealand, Including Tricholomopsis Scabra Sp. Nov

Phytotaxa 288 (1): 069–076 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.288.1.7 The fungal genus Tricholomopsis (Agaricales) in New Zealand, including Tricholomopsis scabra sp. nov. JERRY A. COOPER1* & DUCKCHUL PARK2 1 Landcare Research, PO Box 69040, Lincoln 7640, New Zealand 2 Landcare Research, Private Bag 92170, Auckland 1142, New Zealand *e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The status of the genus Tricholomopsis (Agaricales) in New Zealand is reviewed. T. rutilans is a species described from the northern hemisphere and recorded from plantations of exotic Pinus radiata in New Zealand. Historical collections identified as T. rutilans were subjected to morphological and phylogenetic analysis. The results show that most of these collections refer to T. ornaticeps, originally described from New Zealand native forests. The presence in New Zealand of T. rutilans was not confirmed. Collections of Tricholomopsis from native forests and bush also include a newly described species, T. scabra, which is characterised by a distinctly scabrous pileus. The new species is phylogenetically and morphologically distinct but related to T. ornaticeps. T. ornaticeps and T. scabra are currently known only from New Zealand and the former has extended its habitat to include exotic conifer plantations. Keywords: conifer plantations, Pinus radiata, Southern Hemisphere, Tricholomopsis rutilans, Agaricales Introduction Tricholomopsis Singer (1939: 56) is a genus of saprophytic agaricoid fungi with yellow lamellae, a fibrillose or squamulose dry pileus with red or yellow tones, and it is usually associated with decaying wood. -

Some Critically Endangered Species from Turkey

Fungal Conservation issue 4: February 2014 Fungal Conservation Note from the Editor This issue of Fungal Conservation is being put together in the glow of achievement associated with the Third International Congress on Fungal Conservation, held in Muğla, Turkey in November 2013. The meeting brought together people committed to fungal conservation from all corners of the Earth, providing information, stimulation, encouragement and general happiness that our work is starting to bear fruit. Especial thanks to our hosts at the University of Muğla who did so much behind the scenes to make the conference a success. This issue of Fungal Conservation includes an account of the meeting, and several papers based on presentations therein. A major development in the world of fungal conservation happened late last year with the launch of a new website (http://iucn.ekoo.se/en/iucn/welcome) for the Global Fungal Red Data List Initiative. This is supported by the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, which also made a most generous donation to support participants from less-developed nations at our conference. The website provides a user-friendly interface to carry out IUCN-compliant conservation assessments, and should be a tool that all of us use. There is more information further on in this issue of Fungal Conservation. Deadlines are looming for the 10th International Mycological Congress in Thailand in August 2014 (see http://imc10.com/2014/home.html). Conservation issues will be featured in several of the symposia, with one of particular relevance entitled "Conservation of fungi: essential components of the global ecosystem”. There will be room for a limited number of contributed papers and posters will be very welcome also: the deadline for submitting abstracts is 31 March. -

Study of Biological Activity of Tricholoma Equestre Fruiting Bodies and Their Safety for Human

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository European Food Research and Technology (2018) 244:2255–2264 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-018-3134-0 ORIGINAL PAPER Study of biological activity of Tricholoma equestre fruiting bodies and their safety for human Bożena Muszyńska1 · Katarzyna Kała1 · Jelena Radović2 · Katarzyna Sułkowska‑Ziaja1 · Agata Krakowska3 · Joanna Gdula‑Argasińska4 · Włodzimierz Opoka3 · Tatjana Kundaković2 Received: 11 June 2018 / Revised: 3 July 2018 / Accepted: 6 July 2018 / Published online: 31 July 2018 © The Author(s) 2018 Abstract One of the species of mushrooms authorized for sale in some countries—Tricholoma equestre—can be harmful, and its excessive consumption can lead to serious health problems. Many authors have pointed to the relationship between the consumption of the T. equestre and the occurrence of rhabdomyolysis. The aim of this study was to analyze the composition of biologically active substances in the T. equestre fruiting bodies, and determine their biological activity. The main aim of the analyses performed in the present study was to determine whether the T. equestre is safe or dangerous for consumption by humans. The obtained results, in addition to the existing reports on poisoning caused by T. equestre consumption, are another reason to not take the risk of consuming the fruiting bodies of this species, as the natural environment is rich in other species of edible mushrooms that are not only tasty, but also exhibit healing properties. Keywords Antioxidant activity · Pro-inflammatory activity · Edible mushrooms · Tricholoma equestre · Rhabdomyolysis Introduction flavovirens)—can be harmful, and its excessive consumption can lead to health problems [1–7]. -

The North American <I>Leucopaxillus Monticola</I> (<I>L. Cerealis</I

MYCOTAXON Volume 109, pp. 469–475 July–September 2009 The North American Leucopaxillus monticola (L. cerealis complex) newly recorded from Italy Alfredo Vizzini1 & Marco Contu2 [email protected] Dipartimento di Biologia Vegetale, Università di Torino Viale Mattioli 25, 10125 Torino, Italy 2 [email protected] Via Traversa via Roma, 12 (I Gioielli 2) - 07026 Olbia, Sassari, Italy Abstract — Collections of an interesting small whitish Leucopaxillus, found in Italian Larix forests, are described and illustrated. This taxon, well characterized by a small pileus with a sulcate margin, a polypore-like odour, and abundant filamentous cheilocystidia, is here described as a minor aberrant form of L. monticola. A discussion on its taxonomic position within Leucopaxillus and notes on closely related species are also added. Key words — Agaricales, tricholomatoid clade, Tricholomataceae, taxonomy Introduction According to recent molecular studies, the genus Leucopaxillus Boursier clusters in the tricholomatoid clade sensu Matheny, where together with Clitocybe (Fr.) Staude, Collybia (Fr.) Staude, Lepista (Fr.) W.G. Sm., and Tricholoma (Fr.) Staude it forms the family Tricholomataceae s.s. (Moncalvo et al. 2002, Matheny et al. 2006). Within this genus, the complex of L. cerealis (Lasch) Singer 1962 [(= L. albissimus (Peck) Singer 1939 s.l., fide Singer 1986)] includes numerous taxa exhibiting whitish basidiomata that are often difficult to circumscribe because they have been recognized based mainly on basidioma stature, organoleptic features (context taste and odour), and subtle variations in microanatomy (i.e., pileipellis structure, sporal morphology and ornamentations, degree of the amyloid reaction, presence or absence of cheilocystidia). Given the lack of evidence from sequence data, it is presently difficult to make an informed choice between a splitting attitude, i.e. -

An Asian Edible Mushroom, Macrocybe Gigantea: Its Distribution and ITS-Rdna Based Phylogeny

Mycosphere 7 (4): 525–530 (2016)www.mycosphere.org ISSN 2077 7019 Article Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/7/4/11 Copyright © Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences An Asian edible mushroom, Macrocybe gigantea: its distribution and ITS-rDNA based phylogeny Razaq A1*, Nawaz R2 and Khalid AN2 1Discipline of Botany, Faculty of Fisheries and Wildlife, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences (UVAS), Ravi Campus, Pattoki, Pakistan 2Department of Botany, University of the Punjab, Lahore. 54590, Pakistan. Razaq A, Nawaz R, Khalid AN 2016 – An Asian edible mushroom, Macrocybe gigantea: its distribution and ITS-rDNA based phylogeny. Mycosphere 7(4), 525–530, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/7/4/11 Abstract An updated phylogeny of Macrocybe, a rare pantropical genus, is presented, and new insights regarding the distribution of M. gigantea are given. At the end of last century, this genus was segregated from Tricholoma on morphological and molecular data yet it is still being treated under Tricholoma. In the phylogenetic analysis based on ITS-rDNA, we observed the monophyletic lineage of Macrocybe from the closely related genera Calocybe and Tricholoma. Six collections of M. gigantea, a syntype, re-collected and sequenced from Pakistan, clustered with Chinese and Indian collections which are available in GenBank under Tricholoma giganteum, an older name. The purpose of this work is to support Macrocybe as a separate genus from Tricholoma and Calocybe using ITS-rDNA based phylogeny. Key words – Calocybe – macro fungi – Siderophilous granulation – Tricholoma Introduction Macrocybe Pegler & Lodge accommodates those tricholomatoid species which have large, fleshy, white, cream to grayish ochraceous, convex, umbonate to depressed basidiomata.