Historic Farmsteads Preliminary Character Statement: East Midlands Region Acknowledgements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RISE up STAND out This Guide Should Cover What You Need to Know Before You Apply, but It Won’T Cover Everything About College

RISE UP STAND OUT This guide should cover what you need to know before you apply, but it won’t cover everything about College. We 2020-21 WELCOME TO know that sometimes you can’t beat speaking to a helpful member of the VIRTUAL team about your concerns. OPEN Whether you aren’t sure about your bus EVENTS STAMFORD route, where to sit and have lunch or want to meet the tutors and ask about your course, you can Live Chat, call or 14 Oct 2020 email us to get your questions answered. COLLEGE 4 Nov 2020 Remember, just because you can’t visit 25 Nov 2020 us, it doesn’t mean you can’t meet us! 20 Jan 2021 Find out more about our virtual open events on our website. Contents Our Promise To You ..............................4 Childcare ....................................................66 Careers Reference ................................. 6 Computing & IT..................................... 70 Facilities ........................................................ 8 Construction ............................................74 Life on Campus ...................................... 10 Creative Arts ...........................................80 Student Support ....................................12 Hair & Beauty ......................................... 86 Financial Support ................................. 14 Health & Social Care .......................... 90 Advice For Parents ...............................16 Media ........................................................... 94 Guide to Course Levels ......................18 Motor Vehicle ........................................ -

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources 'Order Of

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers for the Avon.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223 - date 1592. ‘Regulation of the River Avon.’ Hampshire Record Office. 24M82/PZ3. 1590-91. ‘Return of the Ports, Creeks and Landing places in England. 1575.’ The National Archives. SP12/135 dated 1575. ‘Will, Inventory of John Moody (Mowdy) of Kings Somborne, Hampshire. Tailor.’ Hampshire Record Office. 1697A/099. 1697. ‘Will, Inventory of Joseph Warne of Bisterne, Ringwood, Hampshire, Yeoman.’ Hampshire Record Office 1632AD/87. ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223. 1592. Printed official records from before 1600 Acts of the Privy Council. 1591-92. Calendar of Close Rolls. 1227-1509, 62 volumes. Calendar of Fine Rolls. 1399-1509, 11 volumes. Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous. 1216-1509, 21 volumes. Calendar of Liberate Rolls. 1226-1272, 6 volumes. Calendar of Memoranda Rolls. (Exchequer.) 1326-1327. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1226-1509, 59 volumes. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1547-1583, 19 volumes. Curia Regis Rolls. Volume 16. 21-26 Henry 3. Letters and Papers Foreign and Domestic of the Reign of Henry VIII. 1519-1547, 36 volumes. Liber Assisarum et Placitorum Corone. 23 Edward I. The Parliamentary Rolls of Medieval England. 1272 – 1504. (CD Version 2005.) 218 Placitorum in Domo Capitulari Westmonasteriensi Asservatorum Abbreviatio. (Abbreviatio Placitorum.) 1811. Rotuli Hundredorum. Volume I. Statutes at Large. 42 Volumes. Statutes of the Realm. 12 Volumes. Year Books of the Reign of King Edward the Third. Rolls Series. Year XIV. Printed offical records from after 1600 Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reign of Charles I. -

History of Lincolnshire Waterways

22 July 2005 The Sleaford Navigation Trust ….. … is a non-profit distributing company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales (No 3294818) … has a Registered Office at 10 Chelmer Close, North Hykeham, Lincoln, LN6 8TH … is registered as a Charity (No 1060234) … has a web page: www.sleafordnavigation.co.uk Aims & Objectives of SNT The Trust aims to stimulate public interest and appreciation of the history, structure and beauty of the waterway known as the Slea, or the Sleaford Navigation. It aims to restore, improve, maintain and conserve the waterway in order to make it fully navigable. Furthermore it means to restore associated buildings and structures and to promote the use of the Sleaford Navigation by all appropriate kinds of waterborne traffic. In addition it wishes to promote the use of towpaths and adjoining footpaths for recreational activities. Articles and opinions in this newsletter are those of the authors concerned and do not necessarily reflect SNT policy or the opinion of the Editor. Printed by ‘Westgate Print’ of Sleaford 01529 415050 2 Editorial Welcome Enjoy your reading and I look forward to meeting many of you at the AGM. Nav house at agm Letter from mick handford re tokem Update on token Lots of copy this month so some news carried over until next edition – tokens, nav house description www.river-witham.co.uk Martin Noble Canoeists enjoying a sunny trip along the River Slea below Cogglesford in May Photo supplied by Norman Osborne 3 Chairman’s Report for July 2005 Chris Hayes The first highlight to report is the official opening of Navigation House on June 2nd. -

A Book of Dovecotes

A B O O K O F D O V EC OT E S ’e BY A R THU R Oil éfOOKE A UTHOR OF “ THE FOREST OF D EAN ” T . N . FOUL IS PU BLISHE , R LOND ON E DI N BU GH 69' BO , R , ST ON Thi s wo rk i s publi she d by F O U L IS T . N . LONDON ! 1 Gre at R ussell St e e t W . C . 9 r , EDINBU R GH 1 5 Fre d e ri ck S tre e t BOSTON 1 5 A shburton Place ' L e R a P/i llz s A en t ( y r j , g ) A nd ma a so be o d e re d th ou h the o o wi n a enci e s y l r r g f ll g g , whe re the work m ay be exami ne d A U STR A LA S IA ! The O ord U ni ve si t re ss Cathe d a ui di n s xf r y P , r l B l g , 20 F i nd e s Lane M e bourne 5 l r , l A NA D A ! W . C . e 2 Ri ch m o nd Stre e t . We st To onto C B ll , 5 , r D NM A R K ! A aboule va rd 28 o e nh a e n E , C p g (N 'r r ebr os B oglza n d e l) Publis hed i n N ovem é e r N in e teen H un dr e d a n d Pr in ted i n S cotla nd by T D E d z n é u r /z . -

Evolution in the Rock Dove: Skeletal Morphology Richard F. Johnston

The Auk 109(3):530-542, 1992 EVOLUTION IN THE ROCK DOVE: SKELETAL MORPHOLOGY RICHARD F. JOHNSTON Museumof NaturalHistory and Department of Systematicsand Ecology, 602 DycheHall, The Universityof Kansas,Lawrence, Kansas 66045, USA ABSTRACT.--Domesticpigeons were derived from Rock Doves (Columbalivia) by artificial selection perhaps 5,000 ybp. Fetal pigeon populations developed after domesticsescaped captivity; this began in Europe soon after initial domesticationsoccurred and has continued intermittently in other regions. Ferals developed from domesticstocks in North America no earlier than 400 ybp and are genealogicallycloser to domesticsthan to European ferals or wild RockDoves. Nevertheless, North American ferals are significantlycloser in skeletalsize and shapeto Europeanferals and Rock Doves than to domestics.Natural selectionevidently has been reconstitutingreasonable facsimiles of wild size and shape phenotypesin fetal pigeonsof Europeand North America.Received 17 April 1991,accepted 13 January1992. Man, therefore, may be said to have been and southwestern Asia; this is known to be true trying an experiment on a gigantic scale; in more recent time (Darwin 1868; N. E. Bal- and it is an experimentwhich nature dur- daccini, pers. comm.). Later, pigeons escaping ing the long lapse of time has incessantly captivity either rejoined wild colonies or be- tried [Darwin 1868]. came feral, and are now found in most of the world (Long 1981). European,North African, Of the many kinds of animals examined for and Asiatic ferals may have historiesof -

Britons and Anglo-Saxons: Lincolnshire Ad 400-650

The Archaeological Journal Book Reviews BRITONS AND ANGLO-SAXONS: LINCOLNSHIRE AD 400-650. By Thomas Green. Pp. xvi and 320, Illus 48. The History of Lincolnshire Committee (Studies in the History of Lincolnshire, 3), 2012. Price: £17.95. ISBN 978 090266 825 6. Following the completion of the History of Lincolnshire Committee’s admirable twelve- volume history of the county, this book represents the third of a new series of more detailed studies of the region. Based upon his Ph D thesis, Thomas Green addresses the extent of Anglo-Saxon acculturation of Lincolnshire in the centuries following the withdrawal of the Roman legions, and the late survival of the British kingdom of Lindsey, centred on Lincoln. Despite Lincolnshire’s vulnerability to mass Germanic migration — according to traditional models — the substantial mid-fifth-century and later Anglo-Saxon cremation cemeteries, for which the county is famous, form a broad ring around Lincoln itself, which has little evidence for Anglo-Saxon activity until the mid-seventh century. Lincoln and its hinterland are instead characterized by British practice, particularly metalwork, which is extremely unusual for eastern England. The city is recorded as a metropolitan see in AD 314, and there is archaeological evidence for Romano-British continuity at the church of St Paul-in-the-Bail. Green favours a settlement model derived from Gildas, whereby the post-Roman British kings (‘tyrants’) of Lincoln directed and controlled Anglo-Saxon settlement in the county, potentially employing the migrants as mercenaries, although the argument that their major cremation cemeteries were located on strategic routes into the city is simplistically handled (pp. -

Index of Numbers 1-10 (1980-1990)

Rutland Record Journal of the Rutland Local History & Record Society (formerly the Rutland Record Society) Index of numbers 1-10 (1980-1990) compiled by John Field The Rutland Local History & Record Society Oakham, Rutland, 1994 Registered Charity No. 700273 ISSN 0260-3322 Printed for the Rut1and Local History & Record Society by Leicestershire County Council, Central Print Services, from camera-ready copy prepared by T H McK Clough using Cicero word-processing 1994 Copyright Rut1and Local History & Record Society 1994 CONTENTS Introduction 4 Chronology and Extent of Rutland Record 1-10 4 Index of Contributors and Titles 5 Index of Books Reviewed 8 General Index 9 The Society's Publications inside back cover INTRODUCTION "Is it not time," asked the Editor of the Rutland Record in 1980, "before all is lost, to re-establish our links with the past?" These words were no mere rallying cry in the first issue of this journal. They were to serve as part of the statement of the aims of the Society that had just come into existence and as an invitation to contribute to a journal dedicated to the discovering and reinforcement of the bonds between the old and the new in the county of Rutland. The issues of Rutland Record indexed here bear witness to the strength of the response to Bryan Waites's opening challenge. The successive numbers offered aspects of Rutland life and thought, wide in their historical range and topical variety. Matters as diverse as Rutland's origins, the history of cricket, local beer, church architecture, ironstone quarrying, and meteorology were dealt with, each in some depth, in the first five numbers alone. -

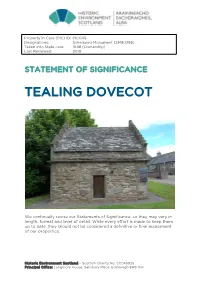

Tealing Dovecot Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC045 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90298) Taken into State care: 1948 (Ownership) Last Reviewed: 2019 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE TEALING DOVECOT We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot 1 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE TEALING DOVECOT CONTENTS 1 Summary 3 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 Statement of significance 3 2 Assessment of values 4 2.1 Background 4 2.2 Evidential values 5 2.3 Historical values 6 2.4 Architectural and artistic values 8 2.5 Landscape and aesthetic values 8 2.6 Natural heritage values 8 2.7 Contemporary/use values 8 3 Major gaps in understanding 8 4 Associated properties 8 5 Keywords 8 Bibliography 9 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Timeline 9 Appendix 2: General history of doocots 11 2 1 Summary 1.1 Introduction Tealing Dovecot is located beside the Home Farm in the centre of Tealing Village, five miles north of Dundee on the A90 towards Forfar. -

EAST NORTHANTS RESOURCE MANAGEMENT FACILITY March

AUGEAN EAST NORTHANTS RESOURCE MANAGEMENT FACILITY APPENDIX CRI LIST OF FORMAL SECTION 42 CONSULTEES March 2012 AUGEAN EAST NORTHANTS RESOURCE MANAGEMENT FACILITY EAST NORTHANTS RESOURCE MANAGEMENT FACILITY IPC PROJECT REFERENCE: WS010001 FORMAL SECTION 42 AND FURTHER SECTION 47 CONSULTATION LIST OF CONSULTEES INCLUDING THOSE NOTIFIED BY THE IPC UNDER REGULATION 9(1)(a) OF THE INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING (ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT) REGULATIONS 2009 Green = Not previously contacted but on IPC list Yellow = Consultees contacted in May 2011 and included on the IPC list Red = Consultee not on list but who contacted Augean recently regarding the gas pipeline Pink = Consultees contacted in May but not on the IPC List Schedule 1 Contact Previously Previously Information sent with letter 19 Responded? Description consulted in May responded? December 2011 2011 NTS S.48 Update enclosed advert table enclosed FORMAL SECTION 42 CONSULTEES The Relevant A Pritchard Regional East Midlands Council Planning Body Phoenix House Web link Nottingham Road No - Yes Yes provided Melton Mowbray Leicestershire LE13 0UL The Relevant B Stewart Regional East of England Regional Letter Planning Body Strategy Board Web link returned. Not c/o East of England No - Yes Yes provided at this Local Government Association address. Flempton House Flempton AU/KCE/SPS/1604/01 1 March 2012 WS010001/ENRMF/CONSAPPCRI 1 AU_KCEp11277.docx AUGEAN EAST NORTHANTS RESOURCE MANAGEMENT FACILITY Schedule 1 Contact Previously Previously Information sent with letter 19 Responded? Description -

Fuel Supply and Agriculture in Post-Medieval England

Fuel supply and agriculture in post-medieval England fuel supply and agriculture in post-medieval england by Paul Warde and Tom Williamson Abstract Historians researching the character of fuel supplies in early modern England have largely focused on the relative contributions made by coal and the produce of managed woodland, especially with an eye to quantification. This has been to the neglect of the diversity of regional and local fuel economies, and their relationship with landscape, social structure, and infrastructural changes. This article highlights the wide range of other fuels employed, both domestically and industrially, in this period; examines the factors which shaped the character of local fuel economies, and the chronology with which these were altered and eroded by the spread of coal use; and looks briefly at the implications of this development for farming and land management. A number of economic and environmental historians have, over the years, suggested that England made the transition from an organic to a fossil-fuel economy long before the conven- tional ‘industrial revolution’ of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Nef argued in the 1930s that, by the sixteenth century, as a consequence of a serious shortage of wood caused by industrial expansion and population growth, coal was already becoming the main supplier of thermal energy in the country.1 Nef’s ideas were challenged by Coleman,2 and somewhat nuanced by Hatcher,3 but the importance of an ‘early’ transition to a coal economy – occurring before the end -

Amble Remembers the First World War

AMBLE REMEMBERS THE FIRST WORLD WAR WRITTEN AND COMPILED BY HELEN LEWIS ON BEHALF OF AMBLE TOWN COUNCIL The assistance of the following is gratefully acknowledged: Descendants of the Individuals Amble Social History Group The Northumberland Gazette The Morpeth Herald Ancestry Commonwealth War Graves Commission Soldiers Died in the Great War Woodhorn Museum Archives Jane Dargue, Amble Town Council In addition, the help from the local churches, organisations and individuals whose contributions were gratefully received and without whom this book would not have been possible. No responsibility is accepted for any inaccuracies as every attempt has been made to verify the details using the above sources as at September 2019. If you have any accurate personal information concerning those listed, especially where no or few details are recorded, or information on any person from the area covered, please contact Amble Town Council on: 01665 714695 or email: [email protected] 1 Contents: What is a War Memorial? ......................................................................................... 3 Amble Clock Tower Memorial ................................................................................... 5 Preservation and Restoration ................................................................................. 15 Radcliffe Memorial .................................................................................................. 19 Peace Memorial ...................................................................................................... -

Land Or Gold? Changing Perceptions of Landscape in Viking Age Lincolnshire

assemblage 11 (2011): 15-33 Land or Gold? Changing Perceptions of Landscape in Viking Age Lincolnshire by LETTY TEN HARKEL This paper looks at the relationship between political conflict and changing perceptions of landscape in England between the ninth and early eleventh centuries AD, focusing on the modern county of Lincolnshire. The period between the ninth and early eleventh centuries AD was a period of continuous conflict, characterised by the Viking raids and subsequent Scandinavian settlement, followed by the unification of England as a result of the West Saxon expansion, and its subsequent conquest by the kings of Denmark. Using different types of material culture, including settlements, metal dress-accessories and funerary sculpture, this paper addresses the relationship between foreign settlement and/or territorial expansion, and the commoditisation of land and its effect on landscape perception. Keywords: Lincolnshire, Viking, conflict archaeology, landscape archaeology, material culture. Introduction initial Viking raids that were documented by ecclesiastical chroniclers indeed fit this profile. The Anglo-Saxon period witnessed some major The first recorded Viking attacks on England, changes in the structure of the English which was then still divided into a number of landscape. Many boundaries that still exist in independent Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, occurred the landscape today can be traced back to at in the last two decades of the eighth century. least the late Anglo-Saxon period. Place-name The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (A: 787) records evidence can provide a historical context for that during the reign of King Beorhtric (786- the emergence of individual settlements, which 802), „there came for the first time three ships; in many cases can also be traced back to the and then the reeve rode there … and they killed late Anglo-Saxon period.