Aid in the Context of Conflict, Fragility, and the Climate Emergency Reality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

Briefing Note on Typhoon Goni

Briefing note 12 November 2020 PHILIPPINES KEY FIGURES Typhoon Goni CRISIS IMPACT OVERVIEW 1,5 million PEOPLE AFFECTED BY •On the morning of 1 November 2020, Typhoon Goni (known locally as Rolly) made landfall in Bicol Region and hit the town of Tiwi in Albay province, causing TYPHOON GONI rivers to overflow and flood much of the region. The typhoon – considered the world’s strongest typhoon so far this year – had maximum sustained winds of 225 km/h and gustiness of up to 280 km/h, moving at 25 km/h (ACT Alliance 02/11/2020). • At least 11 towns are reported to be cut off in Bato, Catanduanes province, as roads linking the province’s towns remain impassable. At least 137,000 houses were destroyed or damaged – including more than 300 houses buried under rock in Guinobatan, Albay province, because of a landslide following 128,000 heavy rains caused by the typhoon (OCHA 09/11/2020; ECHO 10/11/2020; OCHA 04/11/2020; South China Morning Post 04/11/2020). Many families will remain REMAIN DISPLACED BY in long-term displacement (UN News 06/11/2020; Map Action 08/11/2020). TYPHOON GONI • As of 7 November, approximately 375,074 families or 1,459,762 people had been affected in the regions of Cagayan Valley, Central Luzon, Calabarzon, Mimaropa, Bicol, Eastern Visayas, CAR, and NCR. Of these, 178,556 families or 686,400 people are in Bicol Region (AHA Centre 07/11/2020). • As of 07 November, there were 20 dead, 165 injured, and six missing people in the regions of Calabarzon, Mimaropa, and Bicol, while at least 11 people were 180,000 reported killed in Catanduanes and Albay provinces (AHA Centre 07/11/2020; UN News 03/11/2020). -

Bristol County

YOUTH JUSTICE VOTER GUIDE AND LEGISLATIVE SCORECARD: MASSACHUSETTS 2020 BRISTOL COUNTY WELCOME LETTER Each year, thousands of young people in Massachusetts come in contact with the juvenile justice system. These young people are disproportionately children of color, children from the child welfare system, children coming from areas of concentrated poverty, and LGBTQ children. For the majority of these young people, interactions with the juvenile justice system are overwhelmingly negative, and lead to poor outcomes and even increased delinquency. Progress in reforming our legal system into one that is fair and works to create positive outcomes for all system-involved youth, creating stronger and safer communities for everyone, is dependent on elected officials who support or oppose these reforms. This non-partisan voter guide is intended to ensure that you, as a voter, know your rights and are informed in our decisions. The primary focus of this voter guide is to provide the voting record of state elected officials currently in office. We also compiled information on resources from MassVOTE and the Massachusetts Chapter of the League of Women Voters regarding candidate forums in contested elections. This voter guide is intended for educational purposes. The above not-for-profit, non-partisan organizations do not endorse any candidates or political parties for public office. Table of Contents WELCOME LETTER IMPORTANT VOTER INFORMATION IMPORTANT ELECTION DATES SPECIAL COVID-19 ELECTION LAWS: VOTE SAFELY BY MAIL THE KEY ISSUES QUESTIONS TO ASK CANDIDATES IN CONTESTED ELECTIONS VOTING RECORD METHODOLOGY KEY TO THE SCORECARD Bristol County State Senators Bristol County State Representatives PARTNERS IMPORTANT VOTER INFORMATION Am I eligible to vote? You must be at least 18 years old, a US citizen on election day and registered to vote at least 10 days before the election. -

Mr Luke Gosling (PDF 110KB)

Submission No 59 Inquiry into Australia’s Relationship with Timor-Leste Name: Mr Luke Gosling Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Foreign Affairs Sub-Committee Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Committee Inquiry into Australia's relationship with Timor-Leste Luke Gosling, Darwin NT 1. Bilateral relations at the parliamentary and government levels; Our deep relationship with Timor-Leste goes back to the Second World War where a group of Australian Commandos with the help of the Timor-Leste people operated from late 1941 until late 1942. The Timorese people suffered greatly, with at least as many civilian casualties as our Forces suffered in the entire War. For a small population that loss was huge. The Commandos and their Timor-Leste colleagues conducted a classic guerilla Warfare campaign against the Japanese Imperial Forces and a unique bond was formed that was covered in a film I co-produced, screened on Channel 9, called ”A Debt of Honor”. (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ofAK6roD4dY&feature=youtu.be&noredirect=1) The title came from a comment by General Peter Cosgrove, Commander of the Australian-led International Force for East Timor (INTERFET), that our intervention was in part repayment of that debt of honor from World War II. Our ongoing relationship with Timor-Leste is an essential one and one that is taken very seriously and taken to heart by people in Darwin, Palmerston and the Top End. The Parliamentary Friends of Timor-Leste group plays an important role in navigating a course for our relationship that connects and strengthens our bonds with our good neighbors and friends in Timor-Leste and the work of ALP International has similarly been providing an important link through capacity building for better governance and more transparent processes in Timor-Leste political parties. -

Influence of Wind-Induced Antenna Oscillations on Radar Observations

DECEMBER 2020 C H A N G E T A L . 2235 Influence of Wind-Induced Antenna Oscillations on Radar Observations and Its Mitigation PAO-LIANG CHANG,WEI-TING FANG,PIN-FANG LIN, AND YU-SHUANG TANG Central Weather Bureau, Taipei, Taiwan (Manuscript received 29 April 2020, in final form 13 August 2020) 2 ABSTRACT:As Typhoon Goni (2015) passed over Ishigaki Island, a maximum gust speed of 71 m s 1 was observed by a surface weather station. During Typhoon Goni’s passage, mountaintop radar recorded antenna elevation angle oscillations, with a maximum amplitude of ;0.28 at an elevation angle of 0.28. This oscillation phenomenon was reflected in the reflectivity and Doppler velocity fields as Typhoon Goni’s eyewall encompassed Ishigaki Island. The main antenna oscillation period was approximately 0.21–0.38 s under an antenna rotational speed of ;4 rpm. The estimated fundamental vibration period of the radar tower is approximately 0.25–0.44 s, which is comparable to the predominant antenna oscillation period and agrees with the expected wind-induced vibrations of buildings. The re- flectivity field at the 0.28 elevation angle exhibited a phase shift signature and a negative correlation of 20.5 with the antenna oscillation, associated with the negative vertical gradient of reflectivity. FFT analysis revealed two antenna oscillation periods at 0955–1205 and 1335–1445 UTC 23 August 2015. The oscillation phenomenon ceased between these two periods because Typhoon Goni’s eye moved over the radar site. The VAD analysis-estimated wind speeds 2 at a range of 1 km for these two antenna oscillation periods exceeded 45 m s 1, with a maximum value of approxi- 2 mately 70 m s 1. -

DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 - 27 Nov 2018 16:39:49

DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 - 27 Nov 2018 16:39:49 DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 Incorporating REVIEW OF INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING edited by Glenn Hauser, http://www.worldofradio.com Items from DXLD may be reproduced and re-reproduced only if full credit be maintained at all stages and we be provided exchange copies. DXLD may not be reposted in its entirety without permission. Materials taken from Arctic or originating from Olle Alm and not having a commercial copyright are exempt from all restrictions of noncommercial, noncopyrighted reusage except for full credits For restrixions and searchable 2018 contents archive see http://www.worldofradio.com/dxldmid.html [also linx to previous years] NOTE: If you are a regular reader of DXLD, and a source of DX news but have not been sending it directly to us, please consider yourself obligated to do so. Thanks, Glenn WORLD OF RADIO 1957 contents: Australia, Brasil, China, Cuba, France and non, Japan/Korea North non, Nigeria and non, Saudi Arabia, Somaliland, Spain, Sudan, Tajikistan/Tibet non, USA, unidentified; contests; what is DX? and the propagation outlook dxld1847_plain 1 / 115 DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 DX LISTENING DIGEST 18-47, November 19, 2018 - WORLD OF RADIO PODCASTS: 27 Nov 2018 16:39:49 SHORTWAVE AIRINGS of WORLD OF RADIO 1957, November 20-26 2018 Tue 0030 WRMI 7730 [confirmed] Tue 0200 WRMI 9955 [confirmed] Tue 2030 WRMI 7780 [confirmed] Wed 1030 WRMI 5950 [zzz] Wed 2200 WRMI 9955 [confirmed] -

Maximum Wind Radius Estimated by the 50 Kt Radius: Improvement of Storm Surge Forecasting Over the Western North Pacific

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 16, 705–717, 2016 www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci.net/16/705/2016/ doi:10.5194/nhess-16-705-2016 © Author(s) 2016. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Maximum wind radius estimated by the 50 kt radius: improvement of storm surge forecasting over the western North Pacific Hiroshi Takagi and Wenjie Wu Tokyo Institute of Technology, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, 2-12-1 Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 152-8550, Japan Correspondence to: Hiroshi Takagi ([email protected]) Received: 8 September 2015 – Published in Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss.: 27 October 2015 Revised: 18 February 2016 – Accepted: 24 February 2016 – Published: 11 March 2016 Abstract. Even though the maximum wind radius (Rmax) countries such as Japan, China, Taiwan, the Philippines, and is an important parameter in determining the intensity and Vietnam. size of tropical cyclones, it has been overlooked in previous storm surge studies. This study reviews the existing estima- tion methods for Rmax based on central pressure or maximum wind speed. These over- or underestimate Rmax because of 1 Introduction substantial variations in the data, although an average radius can be estimated with moderate accuracy. As an alternative, The maximum wind radius (Rmax) is one of the predominant we propose an Rmax estimation method based on the radius of parameters for the estimation of storm surges and is defined the 50 kt wind (R50). Data obtained by a meteorological sta- as the distance from the storm center to the region of maxi- tion network in the Japanese archipelago during the passage mum wind speed. -

Annual Report Annual | 2016–17 Report

DEPARTMENT OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF HOUSE THE OF DEPARTMENT DEPARTMENT OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Annual Report Annual Report | Annual 2016–17 2016–17 DEPARTMENT OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Annual Report 2016–17 © Commonwealth of Australia 2017 ISSN 0157-3233 (Print) ISSN 2201-1730 (Online) This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia Licence. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au. Use of the Coat of Arms The terms under which the Coat of Arms can be used are detailed on the website of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet at www.dpmc.gov.au/pmc/publication/commonwealth-coat-arms-information-and-guidelines. Produced by the Department of the House of Representatives Editing and indexing by Wilton Hanford Hanover Design by Lisa McDonald Printing by CanPrint Communications Unless otherwise acknowledged, all photographs in this report were taken by staff of the Department of the House of Representatives. Front cover image: House of Representatives Chamber. Photo: Getty Images. Back cover image: Roof detail inside the House of Representatives Chamber. Photo: Penny Bradfield, Auspic/DPS. The department welcomes your comments on this report. To make a comment, or to request more information, please contact: Serjeant-at-Arms Department of the House of Representatives Canberra ACT 2600 Telephone: +61 2 6277 4444 Facsimile: +61 2 6277 2006 Email: [email protected] Website: www.aph.gov.au/house/dept Web address for report: www.aph.gov.au/house/ar16-17 ii Department of the House of Representatives To be supplied Annual Report 2016–17 iii About this report The Department of the House of Representatives provides services that allow the House to fulfil its role as a representative and legislative body of the Australian Parliament. -

Showing Their Support

MILITARY FACES COLLEGE BASKETBALL Exchange shoppers Gillian Anderson Harvard coach Amaker set sights on new embodies Thatcher created model for others Xbox, PlayStation in ‘The Crown’ on social justice issues Page 3 Page 18 Back page South Korea to issue fines for not wearing masks in public » Page 5 stripes.com Volume 79, No. 151 ©SS 2020 MONDAY, NOVEMBER 16, 2020 50¢/Free to Deployed Areas WAR ON TERRORISM US, Israel worked together to track, kill al-Qaida No. 2 BY MATTHEW LEE AND JAMES LAPORTA Associated Press WASHINGTON — The United States and Israel worked together to track and kill a senior al-Qaida operative in Iran this year, a bold intelligence operation by the allied nations that came as the Trump ad- ministration was ramping up pres- sure on Tehran. Four current and former U.S. offi- cials said Abu Mohammed al-Masri, al-Qaida’s No. 2, was killed by assas- sins in the Iranian capital in August. The U.S. provided intelligence to the Israelis on where they could find al- Masri and the alias he was using at the time, while Israeli agents carried out the killing, according to two of the officials. The two other officials confirmed al-Masri’s killing but could not provide specific details. Al-Masri was gunned down in a Tehran alley on Aug. 7, the anni- versary of the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Al- Masri was widely believed to have participated in the planning of those attacks and was wanted on terrorism charges by the FBI. -

20 YEARS of GRATITUDE: Home for the Holidays

ShelterBox Update December 2020 20 YEARS OF GRATITUDE: Home for the Holidays As the calendar year comes to a close and we reach the half-way point of the Rotary year, families all over the world are gathering in new ways to find gratefulness in being together, however that may look. Thank to our supporters in 2020, ShelterBox has been able to ensure that over 25,000 families have a home for the holidays. Home is the center of all that we do at ShelterBox, the same way as home is central to our lives, families, and communities. “For Filipinos, home – or ‘bahay’ as we call it – really is where the heart is. It’s the centre of our family life, our social life and very often our working life too. At Christmas especially, being able to get together in our own homes means everything to us.” – Rose Placencia, ShelterBox Operations Philippines The pandemic did not stop natural disasters from affecting the Philippines this year. Most recently a series of typhoons, including Typhoon Goni, the most powerful storm since 2013’s Typhoon Haiyan, devastated many communities in the region. In 2020, before Typhoon Goni struck, ShelterBox had responded twice to the Philippines, in response to the Taal Volcano eruption and Typhoon Vongfong. As we deploy in response to this new wave of tropical storm destruction, Alejandro and his family are just one of many recovering from Typhoon Vongfong who now have a home for the holidays. Typhoon Vongfong (known locally as Ambo) devastated communities across Eastern Samar in the Philippines earlier this year. -

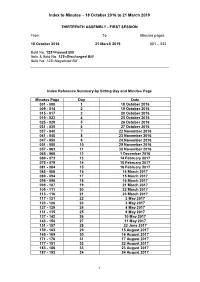

Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 21 March 2019

Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 21 March 2019 THIRTEENTH ASSEMBLY - FIRST SESSION From To Minutes pages 18 October 2016 21 March 2019 001 – 523 Bold No. 123=Passed Bill Italic & Bold No. 123=Discharged Bill Italic No. 123=Negatived Bill Index Reference Summary by Sitting Day and Minutes Page Minutes Page Day Date 001 - 008 1 18 October 2016 009 - 014 2 19 October 2016 015 - 017 3 20 October 2016 019 - 023 4 25 October 2016 025 - 029 5 26 October 2016 031 - 035 6 27 October 2016 037 - 040 7 22 November 2016 041 - 045 8 23 November 2016 047 - 050 9 24 November 2016 051 - 055 10 29 November 2016 057 - 063 11 30 November 2016 065 - 068 12 1 December 2016 069 - 073 13 14 February 2017 075 - 079 14 15 February 2017 081 - 084 15 16 February 2017 085 - 088 16 14 March 2017 089 - 094 17 15 March 2017 095 - 098 18 16 March 2017 099 - 107 19 21 March 2017 109 - 111 20 22 March 2017 113 - 116 21 23 March 2017 117 - 121 22 2 May 2017 123 - 126 23 3 May 2017 127 - 129 24 4 May 2017 131 - 135 25 9 May 2017 137 - 142 26 10 May 2017 143 - 150 27 11 May 2017 151 - 157 28 22 June 2017 159 - 163 29 15 August 2017 165 - 169 30 16 August 2017 171 - 176 31 17 August 2017 177 - 181 32 22 August 2017 183 - 186 33 23 August 2017 187 - 192 34 24 August 2017 1 Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 21 March 2019 193 - 196 35 10 October 2017 197 - 199 36 11 October 2017 201 - 203 37 12 October 2017 205 - 208 38 17 October 2017 209 - 213 39 18 October 2017 215 - 220 40 19 October 2017 221 - 225 41 21 November 2017 227 - 233 42 22 November 2017 235 - 247 43 23 -

Contribution of Grape Skins and Yeast Choice on the Aroma Profiles Of

fermentation Article Contribution of Grape Skins and Yeast Choice on the Aroma Profiles of Wines Produced from Pinot Noir and Synthetic Grape Musts Yifeng Qiao 1,2, Diana Hawkins 2, Katie Parish-Virtue 1, Bruno Fedrizzi 1, Sarah J. Knight 2 and Rebecca C. Deed 1,2,* 1 School of Chemical Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland 1142, New Zealand; [email protected] (Y.Q.); [email protected] (K.P.-V.); [email protected] (B.F.) 2 School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland 1142, New Zealand; [email protected] (D.H.); [email protected] (S.J.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +64-9-3737599 (ext. 81238) Abstract: The aroma profile is a key component of Pinot noir wine quality, and this is influenced by the diversity, quantity, and typicity of volatile compounds present. Volatile concentrations are largely determined by the grape itself and by microbial communities that produce volatiles during fermentation, either from grape-derived precursors or as byproducts of secondary metabolism. The relative degree of aroma production from grape skins compared to the juice itself, and the impact on different yeasts on this production, has not been investigated for Pinot noir. The influence of fermentation media (Pinot noir juice or synthetic grape must (SGM), with and without inclusion Citation: Qiao, Y.; Hawkins, D.; of grape skins) and yeast choice (commercial Saccharomyces cerevisiae EC1118, a single vineyard Parish-Virtue, K.; Fedrizzi, B.; Knight, mixed community (MSPC), or uninoculated) on aroma chemistry was determined by measuring S.J.; Deed, R.C.