Regional Dimensions of the Norman Conquest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download 2015 Minutes

1246 MINUTES OF THE MONTHLY MEETING OF RUDBY PARISH COUNCIL HELD ON MONDAY, 12 JANUARY 2015 AT 7.15 PM IN THE CHAPEL SCHOOLROOM Present: Councillor M Jones (Chairman) Councillors Mrs D Medlock, Messrs. N Bennington, M Fenwick, J Nelson, A Parry, R Readman and N Thompson District Councillor Mrs B Fortune 1 member of the public 1. Apologies for absence were received from Councillors Mrs R Danjoux, Messrs. J Cooper and S Cosgrove. 2. The minutes of last month’s meeting had been circulated and were signed by the Chairman after being agreed as a correct record. 3. Police Report and Neighbourhood Watch The Police report for December was received. Information gathered at the meeting on one of the items in the report will be e mailed to the Police. An e mail was circulated consulting on views on the proposed Police precept for the next financial year. Ringmaster messages included reports on damage to the King’s Head and a blackmail scam. 4. Meeting open to the Public Mr Autherson attended the meeting to bring the Council up to date with changes which are going to happen to the Chapel. They have decided not to go for planning permission but will be having an open consultation evening on 5 February. Leaflets will be distributed throughout the village. The project is going well and it is hoped to open in May. There will be a book exchange but there may be a chance of a branch library. Another suggestion is a CAB session once a week. Linking everything together is the coffee shop. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A history of Richmond school, Yorkshire Wenham, Leslie P. How to cite: Wenham, Leslie P. (1946) A history of Richmond school, Yorkshire, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9632/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk HISTORY OP RICHMOND SCHOOL, YORKSHIREc i. To all those scholars, teachers, henefactors and governors who, by their loyalty, patiemce, generosity and care, have fostered the learning, promoted the welfare and built up the traditions of R. S. Y. this work is dedicated. iio A HISTORY OF RICHMOND SCHOOL, YORKSHIRE Leslie Po Wenham, M.A., MoLitt„ (late Scholar of University College, Durham) Ill, SCHOOL PRAYER. We give Thee most hiomble and hearty thanks, 0 most merciful Father, for our Founders, Governors and Benefactors, by whose benefit this school is brought up to Godliness and good learning: humbly beseeching Thee that we may answer the good intent of our Founders, "become profitable members of the Church and Commonwealth, and at last be partakers of the Glories of the Resurrection, through Jesus Christ our Lord. -

Parish Brochure an Invitation

Parish Brochure An Invitation We, the people of this united Benefice in the young Diocese of Leeds, extend a warm welcome to whoever is called by God to serve among us. We would welcome you into our community in the Vale of Mowbray, set between the Yorkshire Dales and the North York Moors near the county town of Northallerton. Would you be willing to join us, sharing and inspiring our future plans for developing the Christian ministry and mission? A solitary poppy grows amongst the crops in the many fields around our Benefice Our Mission Statement Prayer Dear Lord, As we seek to grow and nurture our Christian faith through your teachings, give us strength to work as a united Benefice and serve our rural communities in your name. Using the resources we have, help us to reach out to young and old in a way that shows our support to them and enable continued growth and awareness of our faith. Our mission, Lord, is to channel your love and compassion in a way that enriches the lives of others. In Jesus’ name we pray. Amen. 1 LOCALITY The united Benefice of the Lower Swale The County town of Northallerton lies is situated in the beautiful countryside about 3 miles from Ainderby Steeple. in the north of the Vale of York in rural It has a wide range of shops including North Yorkshire. Barkers Department store, Lewis & Cooper Delicatessen and other high People living in the Lower Swale area street favourites such as Fat Face, are well positioned for accessing Waterstones, Crew Clothing as well as larger towns and cities in the region, Costa, Caffè Nero and many other coffee and beyond, both by road and public shops. -

Hambleton District Council Election Results 1973-2011

Hambleton District Council Election Results 1973-2011 Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher The Elections Centre Plymouth University The information contained in this report has been obtained from a number of sources. Election results from the immediate post-reorganisation period were painstakingly collected by Alan Willis largely, although not exclusively, from local newspaper reports. From the mid- 1980s onwards the results have been obtained from each local authority by the Elections Centre. The data are stored in a database designed by Lawrence Ware and maintained by Brian Cheal and others at Plymouth University. Despite our best efforts some information remains elusive whilst we accept that some errors are likely to remain. Notice of any mistakes should be sent to [email protected]. The results sequence can be kept up to date by purchasing copies of the annual Local Elections Handbook, details of which can be obtained by contacting the email address above. Front cover: the graph shows the distribution of percentage vote shares over the period covered by the results. The lines reflect the colours traditionally used by the three main parties. The grey line is the share obtained by Independent candidates while the purple line groups together the vote shares for all other parties. Rear cover: the top graph shows the percentage share of council seats for the main parties as well as those won by Independents and other parties. The lines take account of any by- election changes (but not those resulting from elected councillors switching party allegiance) as well as the transfers of seats during the main round of local election. -

Trade Directories 1822-23 & 1833-4 North Yorkshire, Surnames

Trade Directories 1822-23 & 1833-4 North Yorkshire, surnames beginning with P-Q DATE SNAME FNAME / STATUS OCCUPATIONS ADDITIONAL ITEMS PLACE PARISH or PAROCHIAL CHAPELRY 1822-1823 Page Thomas farmer Cowton North Gilling 1822-1823 Page William victualler 'The Anchor' Bellmangate Guisborough 1822-1823 Page William wood turner & line wheel maker Bellmangate Guisborough 1833-1834 Page William victualler 'The Anchor' Bellmangate Guisborough 1833-1834 Page Nicholas butcher attending Market Richmond 1822-1823 Page William Sagon attorney & notary agent (insurance) Newbrough Street Scarborough 1822-1823 Page brewer & maltster Tanner Street Scarborough 1822-1823 Paley Edmund, Reverend AM vicar Easingwold Easingwold 1833-1834 Paley Henry tallow chandler Middleham Middleham 1822-1823 Palliser Richard farmer Kilvington South Kilvington South 1822-1823 Palliser Thomas farmer Kilvington South Kilvington South 1822-1823 Palliser William farmer Pickhill cum Roxby Pickhill 1822-1823 Palliser William lodging house Huntriss Row Scarborough 1822-1823 Palliser Charles bricklayer Sowerby Thirsk 1833-1834 Palliser Charles bricklayer Sowerby Thirsk 1833-1834 Palliser Henry grocery & sundries dealer Ingram Gate Thirsk 1822-1823 Palliser James bricklayer Sowerby Thirsk 1833-1834 Palliser James bricklayer Sowerby Thirsk 1822-1823 Palliser John jnr engraver Finkle Street Thirsk 1822-1823 Palliser John snr clock & watch maker Finkle Street Thirsk 1822-1823 Palliser Michael whitesmith Kirkgate Jackson's Yard Thirsk 1833-1834 Palliser Robert watch & clock maker Finkle -

Holy Trinity Church

Holy Trinity Church Ingham - Norfolk HOLY TRINITY CHURCH INGHAM Ingham, written as “Hincham” in the Domesday Book, means “seated in a meadow”. Nothing of this period survives in the church, the oldest part of which now seems the stretch of walling at the south west corner of the chancel. This is made of whole flints, as against the knapped flint of the rest of the building, and contains traces of a blocked priest’s doorway. In spite of the herringboning of some of the rows of flints, it is probably not older than the thirteenth century. The rest of the body of the church was rebuilt in the years leading up to 1360.Work would have started with the chancel, but it is uncertain when it was begun. The tomb of Sir Oliver de Ingham, who died in 1343, is in the founder’s position on the north side of the chancel, and since the posture of the effigy is, as we shall see, already old fashioned for the date of death, it seems most likely that it was commissioned during his life time and that he rebuilt the chancel (which is Pevsner’s view), or that work began immediately after his death by his daughter Joan and her husband, Sir Miles Stapleton, who also rebuilt the nave. The Stapletons established a College of Friars of the Order of Holy Trinity and St Victor to serve Ingham, and also Walcot. The friars were installed in 1360, and originally consisted of a prior, a sacrist, who also acted as vicar of the parish, and two more brethren. -

Fern House, East Cowton Northallerton, North Yorkshire, DL7 0DH Price Guide £384,950 4 2 4 E Fern House, East Cowton Northallerton, North Yorkshire DL7 0DH

Fern House, East Cowton Northallerton, North Yorkshire, DL7 0DH Price Guide £384,950 4 2 4 E Fern House, East Cowton Northallerton, North Yorkshire DL7 0DH Price Guide £384,950 Location Kitchen / Breakfast Area Northallerton 8.9 miles, Middlesbrough 20.6 miles, Stokesley 19'11" max x 14'7" max (6.07 max x 4.44 max) 18.9 miles (distances are approximate). Excellent road links With a range of floor and wall mounted units, fitted fridge, to the A19, A66 and A1 providing access to Teesside, fitted dishwasher, space for a range oven, Belfast style sink Newcastle, Durham, York, Harrogate and Leeds. Direct train and draining unit with mixer tap over, radiator, door to the services from Northallerton and Darlington to London Kings utility room, window to the front and windows overlooking Cross, Manchester and Edinburgh. International airports: the rear garden. Durham Tees Valley, Newcastle and Leeds Bradford. Utility Room Amenities 13'1" x 4'9" (3.99 x 1.46) East Cowton is a village with a great community spirit, with With stainless steel sink and draining unit, work surfaces many amenities including primary school, village hall, sports with cupboards under, plumbing for a washing machine, and social clubs, church, public house and a small post office space for an American-style fridge freezer, wall-to-ceiling which doubles up as the village shop. storage cupboards, radiator, window to the rear, door to the Accommodation Comprises: garage and stable door leading out to the rear. First Floor Landing Entrance Hall With window overlooking the rear garden, cupboard with The entrance vestibule has a door leading into the main radiator and storage and doors to all first floor rooms. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939 Jennings, E. How to cite: Jennings, E. (1965) The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9965/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Abstract of M. Ed. thesis submitted by B. Jennings entitled "The Development of Education in the North Riding of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939" The aim of this work is to describe the growth of the educational system in a local authority area. The education acts, regulations of the Board and the educational theories of the period are detailed together with their effect on the national system. Local conditions of geograpliy and industry are also described in so far as they affected education in the North Riding of Yorkshire and resulted in the creation of an educational system characteristic of the area. -

"Wherein Taylors May Finde out New Fashions"1

"Wherein Taylors may finde out new fashions"1 Constructing the Costume Research Image Library (CRIL) Dr Jane Malcolm-Davies Textile Conservation Centre, Winchester School of Art 1) Introduction The precise construction of 16th century dress in the British Isles remains something of a conundrum although there are clues to be found in contemporary evidence. Primary sources for the period fall into three main categories: pictorial (art works of the appropriate period), documentary (written works of the period such as wardrobe warrants, personal inventories, personal letters and financial accounts), and archaeological (extant garments in museum collections). Each has their limitations. These three sources provide a fragmentary picture of the garments worn by men and women in the 16th century. There is a need for further sources of evidence to add to the partial record of dress currently available to scholars and, increasingly, those who wish to reconstruct dress for display or wear, particularly for educational purposes. The need for accessible and accurate information on Tudor dress is therefore urgent. Sources which shed new light on the construction of historic dress and provide a comparison or contrast with extant research are invaluable. This paper reports a pilot project which attempted to link the dead, their dress and their documents to create a visual research resource for 16th century costume. 2) The research problem There is a fourth primary source of information that has considerable potential but as yet has been largely overlooked by costume historians. Church effigies are frequently life-size, detailed and dressed in contemporary clothes. They offer a further advantage in the portrayal of many middle class who do not appear in 1 pictorial sources in as great a number as aristocrats. -

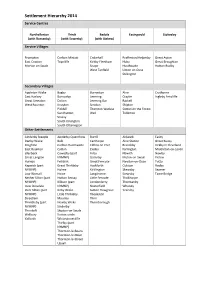

LDF05 Settlement Hierarchy (IPGN) 2014

Settlement Hierarchy 2014 Service Centres Northallerton Thirsk Bedale Easingwold Stokesley (with Romanby) (with Sowerby) (with Aiskew) Service Villages Brompton Carlton Miniott Crakehall Brafferton/Helperby Great Ayton East Cowton Topcliffe Kirkby Fleetham Huby Great Broughton Morton on Swale Snape Husthwaite Hutton Rudby West Tanfield Linton on Ouse Stillington Secondary Villages Appleton Wiske Bagby Burneston Alne Crathorne East Harlsey Borrowby Leeming Crayke Ingleby Arncliffe Great Smeaton Dalton Leeming Bar Raskelf West Rounton Knayton Scruton Shipton Pickhill Thornton Watlass Sutton on the Forest Sandhutton Well Tollerton Sessay South Kilvington South Otterington Other Settlements Ainderby Steeple Ainderby Quernhow Burrill Aldwark Easby Danby Wiske Balk Carthorpe Alne Station Great Busby Deighton Carlton Husthwaite Clifton on Yore Brandsby Kirkby in Cleveland East Rounton Catton Exelby Farlington Middleton-on-Leven Ellerbeck Cowesby (part Firby Flawith Newby Great Langton NYMNP) Gatenby Myton-on-Swale Picton Hornby Felixkirk Great Fencote Newton-on-Ouse Potto Kepwick (part Great Thirkleby Hackforth Oulston Rudby NYMNP) Holme Kirklington Skewsby Seamer Low Worsall Howe Langthorne Stearsby Tame Bridge Nether Silton (part Hutton Sessay Little Fencote Tholthorpe NYMNP) Kilburn (part Londonderry Thormanby Over Dinsdale NYMNP) Nosterfield Whenby Over Silton (part Kirby Wiske Sutton Howgrave Yearsley NYMNP) Little Thirkleby Theakston Streetlam Maunby Thirn Thimbleby (part Newby Wiske Thornborough NYMNP) Sinderby Thrintoft Skipton-on-Swale Welbury Sutton under Yafforth Whitestonecliffe Thirlby (part NYMNP) Thornton-le-Beans Thornton-le-Moor Thornton-le-Street Upsall . -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

05.01.2021.Pdf

WEEKLY STORE SALE Wednesday 5th January 2021 400 BALES FODDER at 10.15am 150 STORE SHEEP at 10.30am 233 CATTLE Comprising of 70 CULL COWS & OTM CATTLE at 11.30am 3 IN CALF COWS 10 BULLS 150 STORE CATTLE Tel: 01609 772034 Fax: 01609 778786 Giles Drew MRICS, FAAV, FLAA www.northallertonauctions.com Chartered Rural Surveyor / Principal Auctioneer [email protected] Mob: 07876 696259 Applegarth Mart, Northallerton, [email protected] North Yorkshire, DL7 8LZ FODDER Lot Vendor Description 50 x 4’ round Bale Barley Straw 1 D&R Reed, Sandhutton (Barn Stored) 90 x 4’ round Bale Oat Straw 2 JM Hall, Darlington (outside Stored) 100 x 4’ round Bale Hay 2019/2020 3 JM Hall, Darlington (inside Stored) 4 SE Shaw, Hutton Bonville 60 x 4’ Round Bale Hay 60 x 4’ Round 1st cut 2020 Silage 5 P&E Ellis, Welbury (analysis Available) STORE LAMBS Pen Vendor No Breed Treatments 1-2 RL Garbutt, Chop Gate 50 Tex x 3-4 R&R Garbutt, Chop Gate 40 Tex x Wormed, Ovi x2 5-6 R&BK Wise, Skipton on Swale 40 Cont x BREEDING CATTLE Pen Vendor No Breed Age Sim Cows In Calf to Sim, Due March 1 MJ Lowcock, Maltby 3 Onwards, Reason for sale, 4-7 yr tested Positive for Johnes’s Disease BULLS Pen Vendor No Breed Age 1 P Dennis, Kirby Sigston 1 Sim 12 2 GW Houlston, Husthwaite 3 AA/Here 10 3 NW Kitching, Ing Cross 2 Hols/fries 8-10 STORE CATTLE Pen Vendor No Breed Age J Linsley, Boldron 10 Cont Stores 1 CA Stobbs, B.