Linen Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hambleton District Council Election Results 1973-2011

Hambleton District Council Election Results 1973-2011 Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher The Elections Centre Plymouth University The information contained in this report has been obtained from a number of sources. Election results from the immediate post-reorganisation period were painstakingly collected by Alan Willis largely, although not exclusively, from local newspaper reports. From the mid- 1980s onwards the results have been obtained from each local authority by the Elections Centre. The data are stored in a database designed by Lawrence Ware and maintained by Brian Cheal and others at Plymouth University. Despite our best efforts some information remains elusive whilst we accept that some errors are likely to remain. Notice of any mistakes should be sent to [email protected]. The results sequence can be kept up to date by purchasing copies of the annual Local Elections Handbook, details of which can be obtained by contacting the email address above. Front cover: the graph shows the distribution of percentage vote shares over the period covered by the results. The lines reflect the colours traditionally used by the three main parties. The grey line is the share obtained by Independent candidates while the purple line groups together the vote shares for all other parties. Rear cover: the top graph shows the percentage share of council seats for the main parties as well as those won by Independents and other parties. The lines take account of any by- election changes (but not those resulting from elected councillors switching party allegiance) as well as the transfers of seats during the main round of local election. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939 Jennings, E. How to cite: Jennings, E. (1965) The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9965/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Abstract of M. Ed. thesis submitted by B. Jennings entitled "The Development of Education in the North Riding of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939" The aim of this work is to describe the growth of the educational system in a local authority area. The education acts, regulations of the Board and the educational theories of the period are detailed together with their effect on the national system. Local conditions of geograpliy and industry are also described in so far as they affected education in the North Riding of Yorkshire and resulted in the creation of an educational system characteristic of the area. -

Holme View Appleton Wiske, Northallerton

S3938 HOLME VIEW APPLETON WISKE, NORTHALLERTON AN ARCHITECTURALLY ATTRACTIVE & SUPERBLY POSITIONED 4-BEDROOMED VILLAGE RESIDENCE OF CHARACTER AND DISTINCTION SITUATED ON LARGE PLOT • UPVC Sealed Unit Double Glazing • Great Scope for Updating & Modernisation • Calor Gas Central Heating • Useful Attached Car Port & Detached Garage • Well Laid Out & Spacious Accommodation • Panoramic Views over Adjacent Countryside Offers in the Region of: £250,000 143 High Street, Northallerton, DL7 8PE Tel: 01609 771959 Fax: 01609 778500 www.northallertonestateagency.co.uk Holme View, Appleton Wiske, Northallerton DL6 2AQ SITUATION are extensive equine activities within the area. Northallerton 8 miles Yarm 6 miles DESCRIPTION Darlington 10 miles A.19 3 miles A.1 10 miles York 35 miles The property comprises a brick built and rendered former Teesside 8 miles Methodist Chapel dating from 1831. The property at present is nicely laid out as a 4-Bedroomed detached house situated on a The village of Appleton Wiske comprises a much sought after large centre of village plot with immense scope for extension, and highly desirable North Yorkshire Village situated amidst refurbishme nt and updating subject to Purchasers requirements open countryside and is particularly well located between and any necessary planning permissions. It is evident however, Northallerton, Yarm, Darlington and Teesside and within easy that the property stands on a plot that would readily access of the A.19 trunk road. The pr operty occupies a very accommodate a large property. pleasant and convenient position in the centre of this much sought after village which enjoys a host of amenities including Internally the property enjoys the benefit of UPVC sealed unit Primary School, Shop, Post Office & Public House. -

(Electoral Changes) Order 2000

545297100128-09-00 23:35:58 Pag Table: STATIN PPSysB Unit: PAG1 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2000 No. 2600 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The District of Hambleton (Electoral Changes) Order 2000 Made ----- 22nd September 2000 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Local Government Commission for England, acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(a), has submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated November 1999 on its review of the district of Hambleton together with its recommendations: And whereas the Secretary of State has decided to give effect to those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 17(b) and 26 of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the District of Hambleton (Electoral Changes) Order 2000. (2) This Order shall come into force— (a) for the purposes of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 1st May 2003, on 10th October 2002; (b) for all other purposes, on 1st May 2003. (3) In this Order— “district” means the district of Hambleton; “existing”, in relation to a ward, means the ward as it exists on the date this Order is made; any reference to the map is a reference to the map prepared by the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions marked “Map of the District of Hambleton (Electoral Changes) Order 2000”, and deposited in accordance with regulation 27 of the Local Government Changes for England Regulations 1994(c); and any reference to a numbered sheet is a reference to the sheet of the map which bears that number. -

Areas Designated As 'Rural' for Right to Buy Purposes

Areas designated as 'Rural' for right to buy purposes Region District Designated areas Date designated East Rutland the parishes of Ashwell, Ayston, Barleythorpe, Barrow, 17 March Midlands Barrowden, Beaumont Chase, Belton, Bisbrooke, Braunston, 2004 Brooke, Burley, Caldecott, Clipsham, Cottesmore, Edith SI 2004/418 Weston, Egleton, Empingham, Essendine, Exton, Glaston, Great Casterton, Greetham, Gunthorpe, Hambelton, Horn, Ketton, Langham, Leighfield, Little Casterton, Lyddington, Lyndon, Manton, Market Overton, Martinsthorpe, Morcott, Normanton, North Luffenham, Pickworth, Pilton, Preston, Ridlington, Ryhall, Seaton, South Luffenham, Stoke Dry, Stretton, Teigh, Thistleton, Thorpe by Water, Tickencote, Tinwell, Tixover, Wardley, Whissendine, Whitwell, Wing. East of North Norfolk the whole district, with the exception of the parishes of 15 February England Cromer, Fakenham, Holt, North Walsham and Sheringham 1982 SI 1982/21 East of Kings Lynn and the parishes of Anmer, Bagthorpe with Barmer, Barton 17 March England West Norfolk Bendish, Barwick, Bawsey, Bircham, Boughton, Brancaster, 2004 Burnham Market, Burnham Norton, Burnham Overy, SI 2004/418 Burnham Thorpe, Castle Acre, Castle Rising, Choseley, Clenchwarton, Congham, Crimplesham, Denver, Docking, Downham West, East Rudham, East Walton, East Winch, Emneth, Feltwell, Fincham, Flitcham cum Appleton, Fordham, Fring, Gayton, Great Massingham, Grimston, Harpley, Hilgay, Hillington, Hockwold-Cum-Wilton, Holme- Next-The-Sea, Houghton, Ingoldisthorpe, Leziate, Little Massingham, Marham, Marshland -

1203 Minutes of the Monthly Meeting of Rudby Parish

1203 MINUTES OF THE MONTHLY MEETING OF RUDBY PARISH COUNCIL HELD ON MONDAY, 13 JANUARY 2014 AT 7.15 PM IN THE CHAPEL SCHOOLROOM Present: Councillor Mr P Stokes (Chairman) Councillors Mesdames D Medlock and R Danjoux, Messrs. J Cooper, M Jones, J Nelson, P Stokes and N Thompson District Councillor Mrs B Fortune PC L Kyle and PCSO D Griffin 1. Apologies for absence were received from County Councillor Mr T Swales and Councillor Mr R Readman. 2. The minutes of last month’s meeting had been circulated and were signed by the Chairman after being agreed as a correct record. 3. Police Report and Neighbourhood Watch PC Kyle said over the last month the following incidents had been reported: Electric fencer unit and battery stolen from Potto; theft of piping in Skutterskelfe; cold callers in Hutton Rudby; car left insecure for a few minutes in Appleton Wiske whilst loading and unloading and items stolen; poachers on land at Appleton Wiske; criminal damage to property at Appleton Wiske. Since the Christmas Safety Campaign began at the end of November, officers have arrested 61 motorists on suspicion of driving while under the influence of drink or drugs. Of these, 28 have been charged. Two new PCSOs will be joining Stokesley Safer Neighbourhood Team – Georgina Lodge and Richard Stringer. PCSO Angie Preston will be returning to Northallerton on 20 January 2014. 4. Meeting open to the public. None present. 5. Matters Arising a. Footpaths. The fence on the footpath at Rudby Bank is due for repair on 29 January. Work has been completed on the footpath and handrail at Sexhow Bank. -

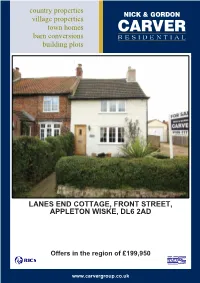

Lanes End Cottage, Front Street, Appleton Wiske, Dl6 2Ad

country properties village properties town homes barn conversions building plots LANES END COTTAGE, FRONT STREET, APPLETON WISKE, DL6 2AD Offers in the region of £199,950 www.carvergroup.co.uk A 3 bedroom cottage of traditional style situated in an ideal central location within Appleton Wiske. A kitchen which is open plan to the dining area and a living room with open fire & views over the village green are just some of the charms this property has to offer. The first floor offers three bedrooms and bathroom, and a lawned rear garden with shed. Entrance Entrance door opens to living room Living room 4.26m x 4.57m (14'0" x 15'0") Living room with double glazed window over looking the front garden and the village green. Exposed timber ceiling beams, feature fireplace with tiled hearth, timber mantle piece and open fire. Under stairs storage units with shelving and cupboard space, timber panel door into kitchen. Landing Stairs to the first floor landing with loft access. Bedroom 1 4.27m x 3.51m (14'0" x 11'6") A double bedroom with window to the front and useful storage cupboard. Kitchen/ Dining room 4.99m x 4.55m (16'4" x 14'11") An open plan kitchen/dining room with tile flooring, windows to the side and rear elevations as well as fully glazed double doors opening to the rear garden. The kitchen is a traditional style with timber work surfaces and cupboards below with a Belfast sink with mixer tap and tile splash back. Four point gas hob built in Siemens electric oven and grill, space for a dishwasher and a freestanding fridge freezer, oil fired central heating boiler and a useful storage Bedroom 2 1.92m x 3.29m (6'4" x 10'10") cupboard. -

Parish Council Winter Newsletter 2020

Appleton Wiske Parish Council InsideSomething this eye issue catching here—anything you want Welcometo ensure ................ the villagers …...…..1 Winter Newsletter Parish Councilsee straight ........ away …….….2 The season of love, lights and quiet contemplation. Health & Wellbeing ……......4 We have officially entered the winter season, traditionally a period of joy Appleton News….……….….6 and happiness, of sparkling lights and excitement, of reflecting on the Christmas Lights ...…….…12 year almost past and for expressing the love and gratitude in our hearts for those who have touched us with theirs. Parish Council Contact Symbolically December is usually a month for gathering with family and friends but this year will be very different for all of us. The government All communication to the have urged us to take personal responsibility this Christmas to limit the Parish Council should be spread of the virus and protect our loved ones, particularly if they are directed to the Clerk: vulnerable. 01609 881822 [email protected] One in three people with coronavirus (COVID-19) have no symptoms and will be spreading it without realising it. The more people you see, the more likely it is that you will catch or spread coronavirus. News email We are all desperate to see our family and friends after such a difficult We frequently circulate “News” year and many of us have formed small bubbles, but there will be some by email. If anyone wishes to of you in the village who will be spending Christmas alone, For some it receive a copy please email will be your idea of bliss, but for others it is the worst possible [email protected] . -

Hambleton District Council Local Green Space Assessment: Combined Recommendations Report

VISTA Design & Assessment HAMBLETON DISTRICT COUNCIL LOCAL GREEN SPACE ASSESSMENT: COMBINED RECOMMENDATIONS REPORT November 2018 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................page 1 METHODOLOGY.........................................................................................................page 5 MAPPING FOR ALL PROPOSED SITES........................................................................page 7 - 36 SITE ALLOCATION SUMMARIES (FOR SITES IN ASSESSMENT PHASE 1 & 2)..............page 37 - 50 Bedale & Brandsby .......................................................................................page 38 Brompton, Carlton Husthwaite & Crakehall..................................................page 39 Easingwold & Great Ayton............................................................................page 40 - 41 Hackforth, Helperby, Huby & Husthwaite.....................................................page 42 Hutton Rudby & Kirkby Fleetham.................................................................page 43 Leeming, Londonderry & Exelby...................................................................page 44 Northallerton, Scruton, Sessay & Snape.......................................................page 45 - 46 Stillington & Stokesley...................................................................................page 47 Thirsk & Thornton le Beans...........................................................................page 48 Topcliffe & West -

NOHTH RIDING YORKSHIRE. [KELLY's Wood William Abel Esq

16 NOHTH RIDING YORKSHIRE. [KELLY'S Wood William Abel esq. Baxby hall, York Wyvill Marmaduke D'Arcy esq. Burton hall, Constable Worsley Lt.-Col. By. Gildart, Belleisle, Richmond,Yorks Burton Worsley Sir William Henry Arthington bart, Boring- Yeoman Ji:>hn Pattison esq. The Close, Brompton, ham hall, York N orthallerton . Wynne-Finch Edward Heneage esq. B.A. The Manor ho. Yeoman Thomas esq. Osmotherley, Northallerton Stokesley Zetland Marquess of K.T., P.C. Aske hall, Richmond; & 19 Arlington street, London S W Clerk of the Peace, William Chas. Trevor, Northallerton. DEPUTY LIEUTENANTS NOT MAGLSTRATES. Bewicke-Copley Brig.-Gen. Robert Calverley .Arlington Dundas Hon. William Fitzwilliam James, The Grange, Be"icke C.B. Sprotborough hall, Doncaster Spofforth Compton-Rickett Rt. Hon. Sir Joseph P.C., M.P. Bar Vyner Robert Charles de Grey esq. Tupholme hall, ham house, East Hoathly, Sussex; & 100 Lancaster Gautby, Horncastle gate, London W • COUNTY POLICE. HEAD QUARTERS, NORTHALLERTOX. The force consists of a. chief constable, a deputy chief constable, II superintendents, 17 inspectors, 23 sergeants & ::153 constables; total 3 ro. There are also 3 inspPctors, 3 sergeants & 27 constables for employment by private tirms. Chairman of Police Committee, William Henry Anthony Wharton esq. Skelton castle, Skelton-in-Clevelan I. Chief Constable, Major R. L. Bower, C.!II.G. Deputy Chief Constable, Superintendent John Wright. Clerk, Superintendent John Henderson, Northallerton. Northallerron Division :-Superintendent, John Wright: *Grange Town, Marton, Normanby, North Ormesby &; Albert Robson, inspector. Northallerton Stations South Bank. Inspector, George Boynton, South Bank Ainderby Steeple, Borrowby, Brompton, NO<rthallerton, Osmotherley. Inspector, John Welford, Thirsk De Langbaurgh East Division: Superintendent, John tachment. -

(Designated Rural Areas in the North East) Order 1997

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1997 No. 624 HOUSING, ENGLAND AND WALES The Housing (Right to Acquire or Enfranchise) (Designated Rural Areas in the North East) Order 1997 Made - - - - 5th March 1997 Laid before Parliament 7th March 1997 Coming into force - - 1st April 1997 The Secretary of State for the Environment, as respects England, in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by section 17 of the Housing Act 1996(1) and section 1AA(3)(a) of the Leasehold Reform Act 1967(2) and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order— Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Housing (Right to Acquire or Enfranchise) (Designated Rural Areas in the North East) Order 1997 and shall come into force on 1st April 1997. Designated rural areas 2. The following areas shall be designated rural areas for the purposes of section 17 of the Housing Act 1996 (the right to acquire) and section 1AA(3)(a) of the Leasehold Reform Act 1967 (additional right to enfranchise)— (a) the parishes in the districts of the East Riding of Yorkshire, Hartlepool, Middlesborough, North East Lincolnshire, North Lincolnshire, Redcar and Cleveland and Stockton-on-Tees specified in Parts I, II, III, IV, V, VI and VII of Schedule 1 to this Order and in the counties of Durham, Northumberland, North Yorkshire, South Yorkshire, Tyne and Wear and West Yorkshire specified in Parts VIII, IX, X, XI, -

Country Properties Village Properties Town Homes Barn Conversions

country properties village properties town homes barn conversions building plots APPLEGARTH MANOR, WELBURY, NORTHALLERTON, DL6 2SF Price on application www.carvergroup.co.uk A large Victorian country residence situated on the edge of the unspoilt North Yorkshire village of Welbury, at the end of a tree-lined driveway. Applegarth Manor has been sympathetically and extensively restored and modernised over recent years. The property provides over 5700 sq ft of living space. In addition, a two-storey coach house incorporates a four-car garage, workshop, gymnasium, games room and snooker room. There are formal grounds and adjoining paddock land; in all extending to around 7 acres. Location Welbury is well placed within 4 miles of the A19, north of Northallerton, south of Darlington and Yarm and east of Richmond. The East Coast Main Line Railway Stations at Darlington and Northallerton provide direct access to Edinburgh and London. Durham Tees Valley Airport lies to the west of Yarm. The village of Welbury provides a public house, nearby village of Appleton Wiske provides a primary school and the market towns of Northallerton, Yarm and Richmond offer a wide range of amenities. History Believed to have been constructed in 1884 by Joseph B L Merryweather, a ship owner from Hartlepool. The panelled walls in the family room are believed to originate from a passenger liner. General Information Oil Fired Central Heating Double-Glazed Windows Comprehensive Security Alarm System with CCTV protection Tax Banding : Hambleton District Council - Band G Services Mains water and electricity. Drainage is to a private system. These particulars do not constitute any part of an offer or contract.