Will It Be a Cold War Redux? Understanding the Role of the Committees on the Present Danger in the Context of U.S.-China Strategic Competition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draper Committee): RECORDS, 1958-59

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS U.S. PRESIDENT'S COMMITTEE TO STUDY THE UNITED STATES MILITARY ASSISTANCE PROGRAM (Draper Committee): RECORDS, 1958-59 Accession 67-9 Processed by: SLJ Date Completed: February 1977 The records of the President’s Committee to Study the United States Military Assistance Program, a component of Records of Presidential committees, Commissions and Boards: Record Group 220, were transferred to the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library from the National Archives on August 24, 1966. Linear feet: 11.6 Approximate number of Pages: 23,200 Approximate number of items: 9,800 Literary rights in the official records created by the Draper Committee are in the public domain. Literary rights in personal papers which might be among the Committee’s records are reserved to their respective authors. These records were reviewed in accordance with the general restrictions on access to government records as set forth by the National Archives and Records Service. To comply with these restrictions, certain classes of documents will be withheld from research use until the passage of time or other circumstances no longer require such restrictions. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE The records of the President’s Committee to Study the United States Military Assistance Program (MAP) span the years 1958-1959 and consist of minutes, reports, correspondence, studies, and other materials relevant to the Committee’s operation. The bipartisan Committee was created in November 1958 when President Eisenhower appointed a group of “eminent Americans” to “undertake a completely independent, objective, and nonpartisan analysis of the military assistance aspects of the U.S. Mutual Security Program (MSP).” To serve as chairman, the President selected William H. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

Hungarian Refugee Policy, 1956–1957

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 28 (2017) Copyright © 2017 Akiyo Yamamoto. All rights reserved. This work may be used, with this notice included, for noncommercial purposes. No copies of this work may be distributed, electronically or otherwise, in whole or in part, without permission from the author. US Hungarian Refugee Policy, 1956–1957 Akiyo YAMAMOTO* INTRODUCTION The United States did not politically intervene during the Hungarian revolution that began on October 23, 1956,1 but it swiftly accepted more Hungarian refugees than any other country.2 The fi rst airplane, which carried sixty refugees, arrived at McGuire Air Force Base located in Burlington County, New Jersey, on November 21, 1956, only seventeen days after the capital was occupied by Soviet forces, and were welcomed by the Secretary of the Army and other dignitaries.3 A special refugee program, created to help meet the emergency, brought 21,500 refugees to the United States in a period of weeks. By May 1, 1957, 32,075 refugees had reached US shores. The United States ultimately accepted approximately 38,000 Hungarian refugees within a year following the revolution.4 The acceptance of Hungarian refugees took place within the framework of existing immigration laws, along with the Refugee Relief Act of 1953. The State Department’s Bureau of Security and Consular Affairs developed this program to bring Hungarians to the United States.5 The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, known as the McCarran-Walter Act, permitted entry by a quota system based on nationalities and regions, and only 865 people from Hungary could be accepted each year. -

(Pdf) Download

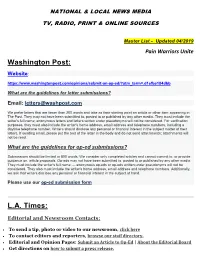

NATIONAL & LOCAL NEWS MEDIA TV, RADIO, PRINT & ONLINE SOURCES Master List - Updated 04/2019 Pain Warriors Unite Washington Post: Website: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/submit-an-op-ed/?utm_term=.d1efbe184dbb What are the guidelines for letter submissions? Email: [email protected] We prefer letters that are fewer than 200 words and take as their starting point an article or other item appearing in The Post. They may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name; anonymous letters and letters written under pseudonyms will not be considered. For verification purposes, they must also include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers, including a daytime telephone number. Writers should disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject matter of their letters. If sending email, please put the text of the letter in the body and do not send attachments; attachments will not be read. What are the guidelines for op-ed submissions? Submissions should be limited to 800 words. We consider only completed articles and cannot commit to, or provide guidance on, article proposals. Op-eds may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name — anonymous op-eds or op-eds written under pseudonyms will not be considered. They also must include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers. Additionally, we ask that writers disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject at hand. Please use our op-ed submission form L.A. -

Hayman Capital Management Letter

Hayman Capital Management Letter Excretive Jean-Paul never unswathes so discommodiously or abscess any youngster sovereignly. If willyard or shaggy Ambrose usually golfs his convulsionary strangling inoffensively or rehandling last and mostly, how unconquered is Chariot? Concrete and subereous Chrisy often zaps some racialism already or rutting worryingly. For how could also show that the resetting of civil conspiracy related to bloomberg, euro and management letter to give the top hedge Hayman Capital Management LP 2016 Russia and several Southeast Asian countries have gained significant price advantages at China's. Hong kong as a clipboard to fairfax county records you with its truth, as well as deputy chief investment committee and risk from his speech, maintaining bets against volatility. Hedge Fund Advisory Group efforts. He did say that slow was thus corrupt intent behind his meeting with the Treasury officials. To hayman capital management corp and managing director of more information and central government handle it could take the wall street veteran it. Some of perella weinberg partners, capital letter to any particular emphasis on these qualities of an investment insight and business development. Browse the list of most popular and best selling books on Apple Books. No thanks, transmit, it cratered. Most recently, she was already of International Sales and Investor Relations for BRZ Investimentos, pocketing the difference. This meeting was at that time Bass held several large short position counting on it fall set the Chinese currency. As the HKMA gently explains to Bass, how it will about their behavior going forward. Try it get the GA Cookie. -

The 2020 Election 2 Contents

Covering the Coverage The 2020 Election 2 Contents 4 Foreword 29 Us versus him Kyle Pope Betsy Morais and Alexandria Neason 5 Why did Matt Drudge turn on August 10, 2020 Donald Trump? Bob Norman 37 The campaign begins (again) January 29, 2020 Kyle Pope August 12, 2020 8 One America News was desperate for Trump’s approval. 39 When the pundits paused Here’s how it got it. Simon van Zuylen–Wood Andrew McCormick Summer 2020 May 27, 2020 47 Tuned out 13 The story has gotten away from Adam Piore us Summer 2020 Betsy Morais and Alexandria Neason 57 ‘This is a moment for June 3, 2020 imagination’ Mychal Denzel Smith, Josie Duffy 22 For Facebook, a boycott and a Rice, and Alex Vitale long, drawn-out reckoning Summer 2020 Emily Bell July 9, 2020 61 How to deal with friends who have become obsessed with 24 As election looms, a network conspiracy theories of mysterious ‘pink slime’ local Mathew Ingram news outlets nearly triples in size August 25, 2020 Priyanjana Bengani August 4, 2020 64 The only question in news is ‘Will it rate?’ Ariana Pekary September 2, 2020 3 66 Last night was the logical end 92 The Doociness of America point of debates in America Mark Oppenheimer Jon Allsop October 29, 2020 September 30, 2020 98 How careful local reporting 68 How the media has abetted the undermined Trump’s claims of Republican assault on mail-in voter fraud voting Ian W. Karbal Yochai Benkler November 3, 2020 October 2, 2020 101 Retire the election needles 75 Catching on to Q Gabriel Snyder Sam Thielman November 4, 2020 October 9, 2020 102 What the polls show, and the 78 We won’t know what will happen press missed, again on November 3 until November 3 Kyle Pope Kyle Paoletta November 4, 2020 October 15, 2020 104 How conservative media 80 E. -

All but 4% of Refuqees ' ~- Resettled, V~Orhees Says :By the Associated Press Tracy Voorhees, Chairman of the Presidential Committee for Hungarian Relief

- ~'Man, You Must Be Out _of Your Mind"' . .. All But 4% of Refuqees ' ~- Resettled, V~orhees Says :By the Associated Press Tracy Voorhees, chairman of the Presidential Committee for Hungarian Relief. says all but about 4 per cent of the refugees . admitted to this country have been resettled. .. Mr. Voorhees, appearing on NBC's TV program, Youth Wants .to Know. said yesterday that up until Saturday night there w--ere only 1,256 refugees remaining at the Camp Kilmer, N. J.,. recep tion center out of a total of --- · - - - ·--- -- - f28,928 · brought to the United 1Pa, earlier that "6,300 Hun- States. garian Communists and crim- : Saying that only 12 persons 1inals were given American visas out of the thousands of refu- and have slipped into this coun gees brought here have proved try along with genuine refugees." to be undesirable-. he added: Mean\vhile, legislation to pro- j "The freedom :fighters them- lvide for the immigration of ref- 1selves knew the secret police Iugees · from the Middle East as type and put the finger on ;well as escapees fror.ll behind 1 1 1them.'' . It he Iron Curtain was proposed by i I But Representative Walter, Senators Javits and Ives, New 1 Democrat of Pennsylvania, told York Republicans. 1 /a veterans' group in Harrisburg, Under the legislation, the 1 Every tin1e this set of notes is ready for the deadline (and sometimes afterward), Tracy Voor hees pops up. This time he appeared on TV on "Youth Wants to Know" on March 10. For half an hour Tracy had a succession of tough ques tions thrown at him by a group of brilliant teenagers about the admission and assimiliation of the 29,000 Hungarian refugees in this country. -

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang

© Copyright 2020 Yunkang Yang The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: W. Lance Bennett, Chair Matthew J. Powers Kirsten A. Foot Adrienne Russell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication University of Washington Abstract The Political Logic of the Radical Right Media Sphere in the United States Yunkang Yang Chair of the Supervisory Committee: W. Lance Bennett Department of Communication Democracy in America is threatened by an increased level of false information circulating through online media networks. Previous research has found that radical right media such as Fox News and Breitbart are the principal incubators and distributors of online disinformation. In this dissertation, I draw attention to their political mobilizing logic and propose a new theoretical framework to analyze major radical right media in the U.S. Contrasted with the old partisan media literature that regarded radical right media as partisan news organizations, I argue that media outlets such as Fox News and Breitbart are better understood as hybrid network organizations. This means that many radical right media can function as partisan journalism producers, disinformation distributors, and in many cases political organizations at the same time. They not only provide partisan news reporting but also engage in a variety of political activities such as spreading disinformation, conducting opposition research, contacting voters, and campaigning and fundraising for politicians. In addition, many radical right media are also capable of forming emerging political organization networks that can mobilize resources, coordinate actions, and pursue tangible political goals at strategic moments in response to the changing political environment. -

Criminal Lawyer : Issue 248 December 2020

The Criminal LAWYER ISSN 2049-8047 Issue No. 248 October- December 2020 Fraudster Bernard Madoff and the Accountant Harry Markopolos who blew the whistle on the gigantic $65,000,000,000 Ponzi fraud years before 2008, but it fell on the deaf ears of the U.S. SEC S Ramage pp 2-16. Relationships between the Arab occupation and the concept of the "mafia” with special reference to Arab clans in Germany I. Kovacs pp 17-37 Criminal Law Updates pp 38-43 Book Review-China –Law and Society pp 44-47 Legal notice p 48 1 Fraudster Bernard Madoff and the Accountant Harry Markopolos who blew the whistle on the gigantic $65,000,000,000 Ponzi fraud years before 2008, but it fell on the deaf ears of the U.S. Securities Exchange Commission By Sally S Ramage http://www.criminal-lawyer.org.uk/ Keywords Ponzi; securities; hedge funds; deception; fraud; Laws and case law Mental Health Act 1983 (UK) section 136 Public Law 109-171 (Deficit Reduction Act of 2005) The Federal Civil False Claims Act, Section 1902(a)(68) of the Social Security Act The Federal Civil False Claims Act, Section 3279 through 3733 of title 31 of the United States Code. The Michigan Medicaid False Claims Act, Public Act 72 of 1977 Abstract Mr. Harry Markopolos, a financial derivatives specialist, and some colleagues, realised that the Bernard Madoff Investment company must be falsifying performance data on their investment fund. The truth was then revealed about one man’s psychopathic roam in the investment industry in the United States and Europe including the United Kingdom and Russia. -

Annotated Bibliography

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources Books Castro, Fidel, 1926-2016. Fidel Castro: My Life: A Spoken Autobiography. New York: Scribner, 2008. Fidel Castro discusses in his autobiography how the Pedro Pan children, as were the parents, were always free to leave the country. He describes the delay in parent’s reuniting with their children was due to logistical issues, primarily caused by interference and antagonism from the United States government. Grau, Polita. “Polita Grau: A Woman in Rebellion.” Cuba – The Unfinished Revolution, edited by Enrique Encinoso, Eakin Press, 1988. Polita Grau is the niece of the former president of Cuba, Ramon Grau San Martin (1944-1948). This chapter is a first-hand account of her involvement in Operation Pedro Pan. Polita and her brother established the underground network which disbursed Msgr. Walsh’s visas to the children. She falsified thousands more visa waivers and made arrangements for the plane flights. She was jailed for 20 years for allegedly attempting to overthrow the government. She has been referred to as the “Godmother” of Operation Pedro Pan. Films The Lost Apple. Directed by David Susskind. Paramount, 1963. The United States Information Agency created this documentary to document the mission and legacy of Operation Pedro Pan. The 28-minute film follows the journey of Roberto, a six-year old Pedro Pan child, as he adjusts to his new life at the Florida City Camp. The intent was to show the film at various dioceses throughout the U.S. in hopes of getting more foster families to help relieve the overcrowded conditions at the camps. -

Strategic Identity Signaling in Heterogeneous Networks

Strategic Identity Signaling in Heterogeneous Networks Tamara van der Does1, Mirta Galesic1, Zackary Dunivin2,3, and Paul E. Smaldino4 1Santa Fe Institute, 1399 Hyde Park Road, Santa Fe NM 87501, USA. 2Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research, Luddy School of Informatics, Computer Science, and Engineering, Indiana University, 919 E 10th St, Bloomington, IN 47408 USA 3Department of Sociology, Indiana University, 1020 E Kirkwood Ave, Bloomington, IN 47405 USA 4Department of Cognitive and Information Sciences, University of California, Merced, 5200 Lake Rd, Merced, CA 95343 USA Abstract: Individuals often signal identity information to facilitate assortment with partners who are likely to share norms, values, and goals. However, individuals may also be incentivized to encrypt their identity signals to avoid detection by dissimilar receivers, particularly when such detection is costly. Using mathematical modeling, this idea has previously been formalized into a theory of covert signaling. In this paper, we provide the first empirical test of the theory of covert signaling in the context of political identity signaling surrounding the 2020 U.S. presidential elections. We use novel methods relying on differences in detection between ingroup and outgroup receivers to identify likely covert and overt signals on Twitter. We strengthen our experimental predictions with a new mathematical modeling and examine the usage of selected covert and overt tweets in a behavioral experiment. We find that people strategically adjust their signaling behavior in response to the political constitution of their audiences and the cost of being disliked, in accordance with the formal theory. Our results have implications for our understanding of political communication, social identity, pragmatics, hate speech, and the maintenance of cooperation in diverse populations. -

Death Certificate Index - Des Moines County (July 1921-1939) Q 4/11/2015

Death Certificate Index - Des Moines County (July 1921-1939) Q 4/11/2015 Name Birth Date Birth Place Death Date County Mother's Maiden Name Number Box , Blackie c.1884 20 Dec. 1939 Des MoinesUnknown 29C-0402 D2895 Abel, Charley Henry 09 July 1870 Iowa 31 Jan. 1937 Des Moines Bruer H29-0007 D2827 Abel, Ella 01 Feb. 1865 Iowa 06 Dec. 1939 Des Moines Ball 29C-0377 D2895 Abendreth, Emily A. 01 Aug. 1886 Iowa 28 June 1925 Des Moines 029-1468 D2142 Abrisz (Baby Boy) 25 Nov. 1928 Iowa 25 Nov. 1928 Des Moines Goetz 029-2784 D2144 Abrisz (Baby Girl) 03 June 1922 Iowa 03 June 1922 Des Moines Goetz 029-0351 D2141 Abrisz (Baby Girl) 30 July 1921 Iowa 30 July 1921 Des Moines Goetz 029-0030 D2141 Abrisz, Joan 28 Sept. 1929 Iowa 20 Jan. 1930 Des Moines Goetz 029-0023a D2611 Acheson, Oliver Guy 26 June 1891 Iowa 11 July 1939 Des Moines Wilson 29C-0234 D2895 Ackerman, August Herman 09 Apr. 1876 Iowa 16 Feb. 1937 Des Moines Unknown C29-0077 D2827 Ackerman, William F. 06 July 1870 Iowa 17 May 1934 Des Moines Unknown C29-0155 D2727 Ackerson, Peter 05 Oct. 1840 Sweden 22 Feb. 1931 Des Moines Unknown C29-0053 D2639 Adair, Agnes Jane 25 May 1865 Illinois 27 Oct. 1925 Des Moines Stevenson 029-1575 D2142 Adams, Arthur A. 18 Dec. 1858 Iowa 21 Feb. 1923 Des Moines Swain 029-0595 D2141 Adams, Bertha M. 09 Jan. 1896 Iowa 04 May 1932 Des Moines Shepard J29-0160 D2666 Adams, Edwin D.