Census Tracts and Block Numbering Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OGC-98-5 U.S. Insular Areas: Application of the U.S. Constitution

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman, Committee on GAO Resources, House of Representatives November 1997 U.S. INSULAR AREAS Application of the U.S. Constitution GAO/OGC-98-5 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 Office of the General Counsel B-271897 November 7, 1997 The Honorable Don Young Chairman Committee on Resources House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: More than 4 million U.S. citizens and nationals live in insular areas1 under the jurisdiction of the United States. The Territorial Clause of the Constitution authorizes the Congress to “make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property” of the United States.2 Relying on the Territorial Clause, the Congress has enacted legislation making some provisions of the Constitution explicitly applicable in the insular areas. In addition to this congressional action, courts from time to time have ruled on the application of constitutional provisions to one or more of the insular areas. You asked us to update our 1991 report to you on the applicability of provisions of the Constitution to five insular areas: Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (the CNMI), American Samoa, and Guam. You asked specifically about significant judicial and legislative developments concerning the political or tax status of these areas, as well as court decisions since our earlier report involving the applicability of constitutional provisions to these areas. We have included this information in appendix I. 1As we did in our 1991 report on this issue, Applicability of Relevant Provisions of the U.S. -

Listing of Eligible Units of Local Government

Eligible Units of Local Government The 426 counties and cities/towns listed below had a population of more than 200,000 people in 2019 according to the Census Bureau. The name of the county or city/town is the name as it appears in the Census Bureau’s City and Town Population Subcounty Resident Population Estimates file. The list below was created using the Census Bureau’s City and Town Population Subcounty Resident Population Estimates file from the 2019 Vintage.1 The data are limited to active governments providing primary general-purpose functions and active governments that are partially consolidated with another government but with separate officials providing primary general-purpose functions.2 The list below also excludes Census summary level entities that are minor civil division place parts or county place parts as these entities are duplicative of incorporated and minor civil division places listed below. State Unit of local government with population that exceeds 200,000 Alabama Baldwin County Alabama Birmingham city Alabama Huntsville city Alabama Jefferson County Alabama Madison County Alabama Mobile County Alabama Montgomery County Alabama Shelby County Alabama Tuscaloosa County Alaska Anchorage municipality Arizona Chandler city Arizona Gilbert town Arizona Glendale city Arizona Maricopa County Arizona Mesa city Arizona Mohave County 1 The Census data file is available at https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/datasets/2010- 2019/cities/totals/sub-est2019_all.csv and was accessed on 12/30/2020. Documentation for the data file can be found at https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/technical-documentation/file-layouts/2010-2019/sub- est2019.pdf. -

2019 TIGER/Line Shapefiles Technical Documentation

TIGER/Line® Shapefiles 2019 Technical Documentation ™ Issued September 2019220192018 SUGGESTED CITATION FILES: 2019 TIGER/Line Shapefiles (machine- readable data files) / prepared by the U.S. Census Bureau, 2019 U.S. Department of Commerce Economic and Statistics Administration Wilbur Ross, Secretary TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION: Karen Dunn Kelley, 2019 TIGER/Line Shapefiles Technical Under Secretary for Economic Affairs Documentation / prepared by the U.S. Census Bureau, 2019 U.S. Census Bureau Dr. Steven Dillingham, Albert Fontenot, Director Associate Director for Decennial Census Programs Dr. Ron Jarmin, Deputy Director and Chief Operating Officer GEOGRAPHY DIVISION Deirdre Dalpiaz Bishop, Chief Andrea G. Johnson, Michael R. Ratcliffe, Assistant Division Chief for Assistant Division Chief for Address and Spatial Data Updates Geographic Standards, Criteria, Research, and Quality Monique Eleby, Assistant Division Chief for Gregory F. Hanks, Jr., Geographic Program Management Deputy Division Chief and External Engagement Laura Waggoner, Assistant Division Chief for Geographic Data Collection and Products 1-0 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1-1 1. Introduction 1.1 What is a Shapefile? A shapefile is a geospatial data format for use in geographic information system (GIS) software. Shapefiles spatially describe vector data such as points, lines, and polygons, representing, for instance, landmarks, roads, and lakes. The Environmental Systems Research Institute (Esri) created the format for use in their software, but the shapefile format works in additional Geographic Information System (GIS) software as well. 1.2 What are TIGER/Line Shapefiles? The TIGER/Line Shapefiles are the fully supported, core geographic product from the U.S. Census Bureau. They are extracts of selected geographic and cartographic information from the U.S. -

My County Works Activity Book

My County Works A County Government Activity Book Dear Educators and Parents, The National Association of Counties, in partnership with iCivics, is proud to present “My County Works,” a county government activity book for children. It is designed to introduce students to counties’ vast responsibilities and the important role counties play in our lives every day. Counties are one of America’s oldest forms of government, dating back to 1634 when the first county governments (known as shires) were established in Virginia. The organization and structure of today’s 3,069 county governments are chartered under state constitutions or laws and are tailored to fit the needs and characteristics of states and local areas. No two counties are exactly the same. In Alaska, counties are called boroughs; in Louisiana, they’re known as parishes. But in every state, county governments are on the front lines of serving the public and helping our communities thrive. We hope that this activity book can bring to life the leadership and fundamental duties of county government. We encourage students, parents and educators to invite your county officials to participate first-hand in these lessons–to discuss specifically how your county works. It’s never too early for children to start learning about civics and how they can help make our communities better places to live, work and play. Please visit www.naco.org for more information about why counties matter and our efforts to advance healthy, vibrant, safe counties across the United States. Matthew Chase Executive Director National Association of Counties Partnering with iCivics The National Association of Counties and iCivics have developed a collection of civic education resources to help young people learn about county government. -

COUNTY PROFILE: Juneau City and Borough, Alaska

COUNTY PROFILE: Juneau City and Borough, Alaska US COUNTY PERFORMANCE The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington analyzed the performance of all 3,142 US counties or county-equivalents in terms of life expectancy at birth, mortality rates for select causes, alcohol use, smoking prevalence, obesity prevalence, and recommended physical activity using novel small area estimation techniques and the most up-to-date county-level information. Explore more results using the interactive US Health Map data visualization (http://vizhub.healthdata.org/subnational/usa). FINDINGS: LIFE EXPECTANCY Sex Juneau City and Borough Alaska National National rank % change 1980-2014 Female 82.5 80.8 81.5 435 +4.9 Male 78.2 76.3 76.7 421 +9.6 life expectancy at birth (years), 2014 Fig. 1: Female life expectancy, 2014 Fig. 2: Male life expectancy, 2014 FINDINGS: ALL-CAUSE MORTALITY Sex Juneau City and Borough Alaska National National rank % change 1980-2014 Female 594.0 667.5 667.8 382 -25.3 Male 798.9 907.6 930.1 261 -38.0 rate per 100,000 population, age-standardized, 2014 Fig. 3: Female all-cause mortality, 2014 Fig. 4: Male all-cause mortality, 2014 http://www.healthdata.org Juneau City and Borough, Alaska | page 1 FINDINGS: ISCHEMIC HEART DISEASE Sex Juneau City and Borough Alaska National National rank % change 1980-2014 Female 72.8 84.1 124.9 84 -52.0 Male 132.4 150.3 191.5 135 -60.8 rate per 100,000 population, age-standardized, 2014 Fig. 5: Female ischemic heart disease, 2014 Fig. -

Census Bureau Geographic Entities and Concepts

Census Bureau Geographic Entities and Concepts Presented by Mike Ratcliffe [email protected] 1 Census Geographic Concepts Legal/Administrative Statistical Areas Areas Examples: Examples: •Census county divisions •States •Census designated places •Counties •Census tracts •Minor civil divisions •Metropolitan and •Incorporated places micropolitan statistical areas •Congressional districts •Urban areas •Legislative areas •Public Use Microdata Areas •School districts •Traffic Analysis Zones 2 Hierarchy of Census Geographic Entities 3 Hierarchy of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Hawaiian Entities 4 5 Hierarchy: State File Summary Levels State County County Subdivision Place (or place part) Census tract Block group Block 6 Blocks • Smallest units of data tabulation—decennial census only, but used by ACS for sample design • Cover the entire nation • Form “building blocks” for all other tabulation geographic areas • Generally bounded by visible features and legal boundaries • 4-digit block numbers completely change from census to census 7 Block Groups • Groups of blocks sharing the same first digit • Smallest areas for which sample (decennial census “long form” as well as ACS) data are available • Size: optimally 1,500 people; range between 300 to 3,000 • Proposed change in minimum threshold to 1,200 people/480 housing units 8 Census Tracts • Small, relatively permanent statistical subdivisions of a county or a statistically equivalent entity. • Increased importance over time for data analysis. • Will be used to present ACS data as well as decennial census data. • Relatively consistent boundaries over time • Size: optimally 4,000 people; range between 1,000 and 8,000 • Proposed change in minimum threshold to 1,200 people • Approximately 65,000 census tracts in U.S. -

Exam School Admissions Task Force

Exam School Admissions Task Force 5.11.2021 1 Overview ▫ Census Tracts vs. Geocodes ▫ Opportunity Index ▫ Top Percentage of School ▫ Percentage of Economically Disadvantaged Students by School ▫ Chicago Tier Replication 2 3 Census Tracts & Geocodes Census Tracts in the city of Boston ● Created by the US Census ● Approximately 178 census tracts in the city of Boston ● Reviewed every 10 years as part of the census process ● American Community Survey data is available by census tract, and is provided with both 1-year and 5-year averages. Geocodes in the city of Boston ● Originally created in the 70’s ● Over 800 geocodes in the city ● Lack of clarity on if / how / when geocodes are re-drawn ● American Community Survey data not available by geocode 6 Opportunity Index What is the Opportunity Index? Individual Neighborhood Past Performance + Characteristics + Each school receives an Opportunity Index Score between .01-.99; this score is a weighted composite of the neighborhood factors, individual student characteristics, and student past performance of each school’s population. Components of the Opportunity Index Individual Neighborhood Past Performance Characteristics ⁃ Academic - Economically ⁃ Attendance Rate Attainment Disadvantaged ⁃ Number of ⁃ Safety + ⁃ Residential + Suspensions ⁃ Physical Disorder Mobility ⁃ ELA and Math ⁃ Median ⁃ Public Housing Course Failures Household ⁃ Recent Immigrant ⁃ ELA and Math Income MCAS Failures ⁃ Foreign Born OI Score Range Number of Schools Less than 0.25 5 ● School OI scores range from 0.17 to 0.89. -

Veterinarian Shortage Situation Nomination Form

4IPSUBHF*% TX175 7.-3164&0/-: NIFAVeterinaryMedicine NationalInstituteofFoodandAgriculture LoanRepaymentProgram(VMLRP) USDepartmentofAgriculture FormNIFA2009Ͳ0001 OMBControlNo.0524ͲϬϬϱϬ VeterinarianShortageSituation ExpirationDate:ϵͬϯϬͬϮϬϭϵ NominationForm Tobesubmitted undertheauthorityofthechiefStateorInsularAreaAnimalHealthOfficial VeterinaryMedicineLoanRepaymentProgram(VMLRP) ThisformmustbeusedforNominationofVeterinarianShortageSituationstotheVeterinaryMedicineLoanRepaymentProgram (VMLRP),AuthorizedUndertheNationalVeterinaryMedicalServiceAct(NVMSA) Note:Pleasesubmitoneseparatenominationformforeachshortagesituation.SeetheStateAnimalHealthOfficial(SAHO)sectionof theVMLRPwebsite(www.nifa.usda.gov/vmlrp)forthenumberofnominationspermittedforyourstateorinsulararea. LocationofVeterinaryShortageAreaforthisNomination Coke, Crockett, Glasscock, Mitchell, Reagan, Sterling, Upton, TX LocationofVeterinaryShortage: (e.g.,County,State/InsularArea;mustbealogisticallyfeasibleveterinarypracticeservicearea) ApproximateCenterofShortageArea Sterling City, 76951 (orLocationofPositionifTypeIII): (e.g.,AddressorCrossStreet,Town/City,andZipCode) OverallPriorityofShortage: @@@@@@@@@@@@@@High Priority TypeofVeterinaryPracticeArea/Discipline/Specialty;ƐĞůĞĐƚŽŶĞͿ͗ @@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@Type II: Private Practice - Rural Area, Food Animal Medicine (awardee obligation: at least 30%@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ FTE or 12hr/week) &ŽƌdLJƉĞ/Žƌ//WƌŝǀĂƚĞWƌĂĐƚŝĐĞ͗ Musƚcover(checkĂtleastone) Maycover ■ BeefCattle BeefCattle DairyCattle DairyCattle -

FY21 Tribal and Insular Area RFA Priority County List (April 2021)

&EPA Office of Transportation and Air Quality United States April 2021 Environmental Protection Agency FY21 Tribal and Insular Area RFA Priority County List In order to receive points under Section V, Criterion #2.B of this RFA, vehicles or equipment proposed for funding must be operated a majority of the time in one of the priority areas listed below. These areas were identified as priority locations for the DERA program because they are designated, as of the release date of this RFA, as Nonattainment Areas or Maintenance Areas for the following National Ambient Air Quality Standards. Data is sourced from EPA’s Green Book of Nonattainment Areas for Criteria (https://www.epa.gov/green- book). a) PM2.5 1997 Standard (Annual: 15 µg/m3, 24-hour: 65 µg/m3) b) PM2.5 2006 Standard (Annual: 15 µg/m3, 24-hour: 35 µg/m3) c) PM2.5 2012 Standard (Annual: 12 µg/m3, 24-hour: 35 µg/m3) d) Ozone (O3) 2008 Standard (8-hour: 0.075ppm) e) Ozone (O3) 2015 Standard (8-hour: 0.070ppm) 2015 8-Hour 2008 8-Hour State County 2012 PM 2.5 2006 PM 2.5 1997 PM 2.5 Ozone Ozone AK Fairbanks North Star Borough X AL Jackson County X AL Jefferson County X AL Shelby County X AL Walker County X AR Crittenden County X AZ Gila County X AZ Maricopa County X X AZ Pinal County X X X AZ Santa Cruz County X AZ Yuma County X CA Alameda County X X X CA Amador County X CA Butte County X X X CA Calaveras County X X CA Contra Costa County X X X CA El Dorado County X X X CA Fresno County X X X X X CA Imperial County X X X X CA Kern County X X X X X CA Kings County X X X X X CA Los Angeles -

CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Kagman II Village, MP 145.781020E LEGEND Chacha Rd Kamas St SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL LABEL STYLE

15.181343N 15.181328N 145.770813E 2010 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Kagman II village, MP 145.781020E LEGEND Chacha Rd Kamas St SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL LABEL STYLE Kalam n K L a la International t m CANADA o asa enook Ln d Lo n o p o K Anonas Dr Federal American Indian Reservation L'ANSE RESVN 1880 Kamas St A n o n a s Off-Reservation Trust Land, D T1880 r Hawaiian Home Land Chacha Rd Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area, Kagman I 19520 Alaska Native Village Statistical Area, KAW OTSA 5690 Tribal Designated Statistical Area American Indian Tribal Subdivision EAGLE NEST DIST 200 K Pugua Ave State American Indian ala basa Tama Resvn 9400 Loop Reservation State Designated Tribal Statistical Area Lumbee SDTSA 9815 Alaska Native Regional Corporation NANA ANRC 52120 State (or statistically equivalent entity) NEW YORK 36 County (or statistically 1014 equivalent entity) MONTGOMERY 031 Lalanghita Rd Minor Civil Division 1016 (MCD)1 Bristol town 07485 Lalangha Ave Census County Division (CCD), Census Subarea (CSA), Hanna CCD 91650 Dokdok Dr Unorganized Territory (UT) Kagman IV 19550 Estate Estate Emmaus 35100 1030 Incorporated Place 1,2 Davis 18100 Census Designated Place (CDP) 2 Incline Village 35100 Tupu Ln 1015 Census Tract 33.07 Lemmai Way Census Block 3 3012 DESCRIPTION SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL Geographic Offset Interstate 3 or Corridor U.S. Highway 2 Kahet Ave Water Body Pleasant Lake 1025 State Highway 4 Swamp, Marsh, or Okefenokee Swamp 1026 Russell St Gravel Pit/Quarry 1029 Other Road 1027 Alageta Rd Cul-de-sac Glacier Bering Glacier Mansanita -

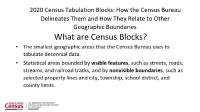

What Are Census Blocks? • the Smallest Geographic Areas That the Census Bureau Uses To

2020 Census Tabulation Blocks: How the Census Bureau Delineates Them and How They Relate to Other Geographic Boundaries What are Census Blocks? • The smallest geographic areas that the Census Bureau uses to tabulate decennial data. • Statistical areas bounded by visible features, such as streets, roads, streams, and railroad tracks, and by nonvisible boundaries, such as selected property lines and city, township, school district, and county limits. • Generally small in area; for example, a block in a city bounded on all sides by streets. In rural areas, may be hundreds of square miles Blocks – Urban area Blocks – Rural area Census Blocks… • cover the entire territory of the United States • nest within all other tabulated census geographic entities and are the basis for all tabulated data. • are defined once a decade and data are available only from the decennial census 100% data (age, sex, race, Hispanic/Latino origin, relationship to householder, and own/rent house). Census Block Numbers • Census blocks are numbered uniquely with a four-digit census block number from 0000 to 9999 within a census tract, which nest within state and county • The first digit of the census block number identifies the block group. Hierarchy of Census Geographic Entities Hierarchy of Census Tribal Geographic Entities How are Census Blocks Delineated? • Census Bureau Algorithm Applied Nationally • Challenge: Visible features and nonvisible boundaries (potential block boundaries) are not evenly distributed nationwide • How do you create a “one size fits all” algorithm? How are Census Tabulation Blocks Delineated? 1. Generate the base block layer of physical features (Hydro and Non- Hydro) – (Roads (primary, secondary, neighborhood, alleys, service drives, private roads, dirt 4WD vehicular trails, railroads, streams/rivers, canals, power lines, pipelines) – Geographic area boundaries (e.g. -

2010 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Rancho San Diego CDP, CA 116.877232W LEGEND E Park Ave Lark St

32.798433N 32.796606N 116.962935W 2010 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Rancho San Diego CDP, CA 116.877232W LEGEND E Park Ave Lark St N Magnolia B Granite Hills Dr a Melody Ln l l Ave a El SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL LABEL STYLE n t y Ave n El Cajon 21712 158.01 e Cajon r S Julian A e St 3rd N v D t Orchard Ln Shady G ll a r N Mollison Ave Ave Mollison N International Roanoke Rd Rd Roanoke 157.01 H e CANADA D St Orlando 21712 e Valley View Blvd n W f ie ld Joliet St D r Federal American Indian E Main St Reservation L'ANSE RESVN 1880 Ave side ny un S Off-Reservation Trust Land, Stony Knoll Rd Rd Knoll Stony Hawaiian Home Land T1880 E Douglas Ave Decker St Prescott Ave Granite Hills 30703 Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area, Alaska Native Village Statistical Area, KAW OTSA 5690 S 1st St St 1st S E Lexington Ave St 2nd S Tribal Designated Statistical Area 156.02 155.01 Crest 17106 Markerry Ave n L k Roc Bradford Rd 156.01 Balanced Euclid Ave American Indian Tribal Norran Ave EAGLE NEST DIST 200 Colinas Paseo Subdivision Shi re D Redwood Ave St Ballard r S 3rd St St 3rd S Doncarol Ave St Dilman S Magnolia Ave Ave Magnolia S 157.03 157.04 State American Indian 158.02 St Dichter Reservation Tama Resvn 9400 Nothomb St St Nothomb Lincoln Ave Ave Lincoln Richandave Ave Garrison Way Claydelle Ave Ave Claydelle Bosworth St E Camden State Designated Tribal t Dumar Ave u Ave Statistical Area Lumbee SDTSA 9815 Farr ag r Ci Andover Rd 1000 Alaska Native Regional C ll NANA ANRC 52120 E Dehesa Rd Corporation nc an to Alderson St St Alderson Benton Pl y State (or