Matai Totara Flood-Plain Forests in South Westland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

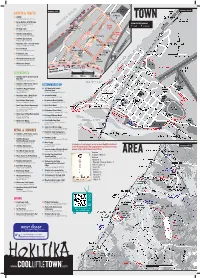

Hokitika Maps

St Mary’s Numbers 32-44 Numbers 1-31 Playground School Oxidation Artists & Crafts Ponds St Mary’s 22 Giſt NZ Public Dumping STAFFORD ST Station 23 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 7448 TOWN Oxidation To Kumara & 2 1 Ponds 48 Gorge Gallery at MZ Design BEACH ST 3 Greymouth 1301 Kaniere Kowhitirangi Rd. TOWN CENTRE PARKING Hokitika Beach Walk Walker (03) 755 7800 Public Dumping PH: HOKITIKA BEACH BEACH ACCESS 4 Health P120 P All Day Park Centre Station 11 Heritage Jade To Kumara & Driſt wood TANCRED ST 86 Revell St. PH: (03) 755 6514 REVELL ST Greymouth Sign 5 Medical 19 Hokitika Craſt Gallery 6 Walker N 25 Tancred St. (03) 755 8802 10 7 Centre PH: 8 11 13 Pioneer Statue Park 6 24 SEWELL ST 13 Hokitika Glass Studio 12 14 WELD ST 16 15 25 Police 9 Weld St. PH: (03) 755 7775 17 Post18 Offi ce Westland District Railway Line 21 Mountain Jade - Tancred Street 9 19 20 Council W E 30 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8009 22 21 Town Clock 30 SEAVIEW HILL ROAD N 23 26TASMAN SEA 32 16 The Gold Room 28 30 33 HAMILTON ST 27 29 6 37 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8362 CAMPCarnegie ST Building Swimming Glow-worm FITZHERBERT ST RICHARDS DR kiosk S Pool Dell 31 Traditional Jade Library 34 Historic Lighthouse 2 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 5233 Railway Line BEACH ST REVELL ST 24hr 0 250 m 500 m 20 Westland Greenstone Ltd 31 Seddon SPENCER ST W E 34 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8713 6 1864 WHARF ST Memorial SEAVIEW HILL ROAD Monument GIBSON QUAY Hokitika 18 Wilderness Gallery Custom House Cemetery 29 Tancred St. -

Ïg8g - 1Gg0 ISSN 0113-2S04

MAF $outtr lsland *nanga spawning sur\feys, ïg8g - 1gg0 ISSN 0113-2s04 New Zealand tr'reshwater Fisheries Report No. 133 South Island inanga spawning surv€ys, 1988 - 1990 by M.J. Taylor A.R. Buckland* G.R. Kelly * Department of Conservation hivate Bag Hokitika Report to: Department of Conservation Freshwater Fisheries Centre MAF Fisheries Christchurch Servicing freshwater fisheries and aquaculture March L992 NEW ZEALAND F'RESTTWATER F'ISHERIES RBPORTS This report is one of a series issued by the Freshwater Fisheries Centre, MAF Fisheries. The series is issued under the following criteria: (1) Copies are issued free only to organisations which have commissioned the investigation reported on. They will be issued to other organisations on request. A schedule of reports and their costs is available from the librarian. (2) Organisations may apply to the librarian to be put on the mailing list to receive all reports as they are published. An invoice will be sent for each new publication. ., rsBN o-417-O8ffi4-7 Edited by: S.F. Davis The studies documented in this report have been funded by the Department of Conservation. MINISTBY OF AGRICULTUBE AND FISHERIES TE MANAlU AHUWHENUA AHUMOANA MAF Fisheries is the fisheries business group of the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. The name MAF Fisheries was formalised on I November 1989 and replaces MAFFish, which was established on 1 April 1987. It combines the functions of the t-ormer Fisheries Research and Fisheries Management Divisions, and the fisheries functions of the former Economics Division. T\e New Zealand Freshwater Fisheries Report series continues the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, Fisheries Environmental Report series. -

May 2019, Issue 4

THE NEWS MAY 2019 S ISSUE 5 REDUCTION READINESS RESPONSE RECOVERY IN THIS ISSUE > Westland bears the brunt of heavy rainfall > AF8 Roadshow > Understanding the risk > New Zealand ShakeOut 2019 > Kid's time! Welcome to our Autumn newsletter! Looking after yourself and your family in an emergency | Readiness plans Many disasters will affect A household emergency plan will help you work out: essential services and possibly n What you will each do in the event n How and when to turn off the water, disrupt your ability to travel or of disasters such as an earthquake, electricity and gas at the main communicate with each other. tsunami, volcanic eruption, flood or switches in your home or business. storm. You may be confined to your home or Turn off gas only if you suspect a n How and where you will meet up during forced to evacuate your neighbourhood. leak, or if you are instructed to do so and after a disaster. In the immediate aftermath of a disaster, by authorities. If you turn the gas off emergency services may not be able to get n Where to store emergency survival you will need a professional to turn it help to everyone as quickly as needed. items and who will be responsible for back on and it may take them weeks to maintaining supplies. This is when you are likely to be most respond after an event. n vulnerable, so it is important to plan to What you will each need to have in your n What local radio stations to tune in to look after yourself and your loved ones getaway kits and where to keep them. -

Rivermouth-Related Shore Erosion at Hokitika and Neils Beach, Westland

Rivermouth-related shore erosion at Hokitika and Neils Beach, Westland Prepared for West Coast Regional Council February 2016 © All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced or copied in any form without the permission of the copyright owner(s). Such permission is only to be given in accordance with the terms of the client’s contract with NIWA. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. Whilst NIWA has used all reasonable endeavours to ensure that the information contained in this document is accurate, NIWA does not give any express or implied warranty as to the completeness of the information contained herein, or that it will be suitable for any purpose(s) other than those specifically contemplated during the Project or agreed by NIWA and the Client. Prepared by: D M Hicks For any information regarding this report please contact: Murray Hicks Sediment Processes +64-3-343 7872 [email protected] National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd PO Box 8602 Riccarton Christchurch 8011 Phone +64 3 348 8987 NIWA CLIENT REPORT No: CHC2016-002 Report date: February 2016 NIWA Project: ELF16506 Quality Assurance Statement Reviewed by: Richard Measures Formatting checked by: America Holdene Approved for release by: Jo Hoyle Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................. 5 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. -

Te Rūnanga O Kaikōura Environmental Management Plan Te Mahere Whakahaere Taiao O Te Rūnanga O Kaikōura

TE POHA O TOHU RAUMATI Te Rūnanga o Kaikōura Environmental Management Plan Te Mahere Whakahaere Taiao o Te Rūnanga o Kaikōura 2007 ii MIHI Tēnā koutou katoa Tēnā koutou katoa E ngā karangatanga e maha he hari anā tēnei To all peoples it is with pleasure we greet mihi atu ki a koutou i runga tonu nei i ngā you with the best of intentions regarding this ahuatanga o te tika me te pono o tēnei kaupapa important issue of caring for our land, our inland manāki taonga ā whenua, ā wai māori, ā wai tai. and coastal waterways. He kaupapa nui whakaharahara te mahi ngātahi It is equally important that our people work with tēnei iwi me ngā iwi katoa e nohonoho nei ki tō all others that share our tribal territory. matou takiwā. Therefore we acknowledge the saying that was Heoi anō i runga i te peha o tōku tupuna Nōku uttered by our ancestor, if I move then so should te kori, kia kori mai hoki koe ka whakatau te you and lay down this document for your kaupapa. consideration. Ko Tapuae-o-Uenuku kei runga hei tititreia mō Tapuae-o-Uenuku is above as a chiefly comb for te iwi the people Ko Waiau toa kei raro i hono ai ki tōna hoa ki te Waiau toa is below also joining with his partner hauraro ko Waiau Uha further south Waiau Uha Ko Te Tai o Marokura te moana i ū mai ai a Te Tai o Marokura is the ocean crossed by Tūteurutira kia tau mai ki tō Hineroko whenua i Tūteurutira where he landed upon the shore raro i Te Whata Kai a Rokohouia of the land of Hineroko beneath the lofty food gathering cliffs of Rokohouia Ko tōna utanga he tāngata, arā ko ngā Tātare o Tānemoehau His cargo was people the brave warriors of Tānemoehau Ā, heke tātai mai ki tēnei ao The descendants have remained to this time. -

+Tuhinga 27-2016 Vi:Layout 1

27 2016 2016 TUHINGA Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa The journal of scholarship and mätauranga Number 27, 2016 Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is a peer-reviewed publication, published annually by Te Papa Press PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand TE PAPA ® is the trademark of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Te Papa Press is an imprint of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tuhinga is available online at www.tepapa.govt.nz/tuhinga It supersedes the following publications: Museum of New Zealand Records (1171-6908); National Museum of New Zealand Records (0110-943X); Dominion Museum Records; Dominion Museum Records in Ethnology. Editorial board: Catherine Cradwick (editorial co-ordinator), Claudia Orange, Stephanie Gibson, Patrick Brownsey, Athol McCredie, Sean Mallon, Amber Aranui, Martin Lewis, Hannah Newport-Watson (Acting Manager, Te Papa Press) ISSN 1173-4337 All papers © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa 2016 Published June 2016 For permission to reproduce any part of this issue, please contact the editorial co-ordinator,Tuhinga, PO Box 467, Wellington. Cover design by Tim Hansen Typesetting by Afineline Digital imaging by Jeremy Glyde Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Number 27, 2016 Contents A partnership approach to repatriation: building the bridge from both sides 1 Te Herekiekie Herewini and June Jones Mäori fishhooks at the Pitt Rivers Museum: comments and corrections 10 Jeremy Coote Response to ‘Mäori fishhooks at the Pitt Rivers Museum: comments 20 and corrections’ Chris D. -

FT1 Australian-Pacific Plate Boundary Tectonics

Geosciences 2016 Annual Conference of the Geoscience Society of New Zealand, Wanaka Field Trip 1 25-28 November 2016 Tectonics of the Pacific‐Australian Plate Boundary Leader: Virginia Toy University of Otago Bibliographic reference: Toy, V.G., Norris, R.J., Cooper, A.F., Sibson, R.H., Little, T., Sutherland, R., Langridge, R., Berryman, K. (2016). Tectonics of the Pacific Australian Plate Boundary. In: Smillie, R. (compiler). Fieldtrip Guides, Geosciences 2016 Conference, Wanaka, New Zealand.Geoscience Society of New Zealand Miscellaneous Publication 145B, 86p. ISBN 978-1-877480-53-9 ISSN (print) : 2230-4487 ISSN (online) : 2230-4495 1 Frontispiece: Near-surface displacement on the Alpine Fault has been localised in an ~1cm thick gouge zone exposed in the bed of Hare Mare Creek. Photo by D.J. Prior. 2 INTRODUCTION This guide contains background geological information about sites that we hope to visit on this field trip. It is based primarily on the one that has been used for University of Otago Geology Department West Coast Field Trips for the last 30 years, partially updated to reflect recently published research. Copies of relevant recent publications will also be made available. Flexibility with respect to weather, driving times, and participant interest may mean that we do not see all of these sites. Stops are denoted by letters, and their locations indicated on Figure 1. List of stops and milestones Stop Date Time start Time stop Location letter Aim of stop Notes 25‐Nov 800 930 N Door Geol Dept, Dunedin Food delivery VT, AV, Nathaniel Chandrakumar go to 930 1015 N Door Geology, Dunedin Hansens in Kai Valley to collect van 1015 1100 New World, Dunedin Shoping for last food supplies 1115 1130 N Door Pick up Gilbert van Reenen Drive to Chch airport to collect other 1130 1700 Dud‐Chch participants Stop at a shop so people can buy 1700 1900 Chch‐Flockhill Drive Chch Airport ‐ Flockhill Lodge beer/wine/snacks Flockhill Lodge: SH 73, Arthur's Pass Overnight accommodation; cook meal 7875. -

GNS Science Miscellaneous Series Report

NHRP Contestable Research Project A New Paradigm for Alpine Fault Paleoseismicity: The Northern Section of the Alpine Fault R Langridge JD Howarth GNS Science Miscellaneous Series 121 November 2018 DISCLAIMER The Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited (GNS Science) and its funders give no warranties of any kind concerning the accuracy, completeness, timeliness or fitness for purpose of the contents of this report. GNS Science accepts no responsibility for any actions taken based on, or reliance placed on the contents of this report and GNS Science and its funders exclude to the full extent permitted by law liability for any loss, damage or expense, direct or indirect, and however caused, whether through negligence or otherwise, resulting from any person’s or organisation’s use of, or reliance on, the contents of this report. BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Langridge, R.M., Howarth, J.D. 2018. A New Paradigm for Alpine Fault Paleoseismicity: The Northern Section of the Alpine Fault. Lower Hutt (NZ): GNS Science. 49 p. (GNS Science miscellaneous series 121). doi:10.21420/G2WS9H RM Langridge, GNS Science, PO Box 30-368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand JD Howarth, Dept. of Earth Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand © Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2018 www.gns.cri.nz ISSN 1177-2441 (print) ISSN 1172-2886 (online) ISBN (print): 978-1-98-853079-6 ISBN (online): 978-1-98-853080-2 http://dx.doi.org/10.21420/G2WS9H CONTENTS ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................................... IV KEYWORDS ......................................................................................................................... V KEY MESSAGES FOR MEDIA ............................................................................................ VI 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 7 2.0 RESEARCH AIM 1.1 — ACQUIRE NEW AIRBORNE LIDAR COVERAGE .............. -

West Coast Sexual Health Services

West Coast Sexual Health Services Listed below are some of the options for sexual health services available on the West Coast. Family Planning For appointments 0800 372 546 Family Planning Nurses can provide advice over the phone on ECP, contraception, and sexual health. Buller District Buller Sexual Health Clinic Outpatients Department (Buller Health) Specialist Sexual Health Service WESTPORT FREE service for all ages for assessment and 03 788 9030 ext 8756 (during clinic hours) treatment of Sexually Transmitted Infections. FREE Condoms. Drop-In Clinic and nurse-led Clinic hours appointments available. Mondays 10.30 to 11.30am. Drop-in Clinic hours Mondays 11.30am to 4.30pm Buller Health 45 Derby Street A Doctor, Rural Nurse Specialist and Practice WESTPORT Nurses provide medical services including sexual 03 788 9277 health. Appointments essential. Coast Medical 61 Palmerston Street A Doctor and Practice Nurses provide medical WESTPORT services including sexual health. Appointments 03 789 5000 essential. Karamea Medical Centre 126 Waverley Street A Rural Nurse Specialist and a Doctor provide KARAMEA medical services including sexual health. Available 03 782 6710 at various times. Appointments essential. Ngakawau Health Centre 1a Main Road A Rural Nurse Specialist and a Doctor provide HECTOR medical services including sexual health. Available 03 788 5062 at various times. Appointments essential. Reefton Integrated Family Health Centre 103 Shiel Street A Doctor, Rural Nurse Specialist and Practice REEFTON Nurses provide medical services including sexual 03 732 8605 health. Appointments essential. Grey District WCDHB Sexual Health Clinic Link Clinic (Grey Base Hospital) Specialist Sexual Health Service GREYMOUTH FREE service for all ages for assessment and 03 769 7400 extn 2874 (during clinic hours) treatment of Sexually Transmitted Infections. -

Waiho River Flooding Risk Assessment MCDEM 2002.Pdf

Report 80295/2 Page i WAIHO RIVER FLOODING RISK ASSESSMENT For MINISTRY OF CIVIL DEFENCE & EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT AUGUST 2002 Report 80295/2 Page ii PROJECT CONTROL Consultant Details Project Leader: Adam Milligan Phone: 04 471 2733 Project Team: Fax: 04 471 2734 Organisation: Optimx Limited Postal Address: P O Box 942, Wellington Peer Reviewer Details Reviewer: David Elms Phone: 03 364 2379 Position: Director Fax: 03 364 2758 Organisation: Optimx Limited Postal Address: Department of Civil Engineering University of Canterbury Private Bag 4800, Christchurch Client Details Client: Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Postal Address: PO Box 5010 Management Wellington Client contact: Richard O’Reilly Phone: 04 473 7363 Project Details Project: Waiho River Flooding Risk Assessment Project No.: 80295 Version Status File Date Approval signatory 1 Draft 80295 MCDEM Waiho River Risk Assessment Report - Aug 2002 David Elms Version 1.doc 2 Final Draft 80295 MCDEM Waiho River Risk Assessment Report - Aug 2002 David Elms Version 2.doc 3 Final 80295 MCDEM Waiho River Risk Assessment Report - Aug 2002 David Elms FINAL.doc This report has been prepared at the specific instructions of the Client. Only the Client is entitled to rely upon this report, and then only for the purpose stated. Optimx Limited accept no liability to anyone other than the Client in any way in relation to this report and the content of it and any direct or indirect effect this report my have. Optimx Limited does not contemplate anyone else relying on this report or that it will be used for any other purpose. Should anyone wish to discuss the content of this report with Optimx Limited, they are welcome to contact the project leader at the address stated above. -

WEST COAST STATUS REPORT Meeting Paper for West Coast Tai Poutini Conservation Board

WEST COAST STATUS REPORT Meeting Paper For West Coast Tai Poutini Conservation Board TITLE OF PAPER STATUS REPORT AUTHOR: Mark Davies SUBJECT: Status Report for the Board for period ending 15 April 2016 DATE: 21 April 2016 SUMMARY: This report provides information on activities throughout the West Coast since the 19 February 2016 meeting of the West Coast Tai Poutini Conservation Board. MARINE PLACE The Operational Plan for the West Coast Marine Reserves is progressing well. The document will be sent out for Iwi comment on during May. MONITORING The local West Coast monitoring team completed possum monitoring in the Hope and Stafford valleys. The Hope and Stafford valleys are one of the last places possums reached in New Zealand, arriving in the 1990’s. The Hope valley is treated regularly with aerial 1080, the Stafford is not treated. The aim is to keep possum numbers below 5% RTC in the Hope valley and the current monitor found an RTC of 1.3% +/- 1.2%. The Stafford valley is also measured as a non-treatment pair for the Hope valley, it had an RTC of 21.5% +/- 6.2%. Stands of dead tree fuchsia were noted in the Stafford valley, and few mistletoe were spotted. In comparison, the Hope Valley has abundant mistletoe and healthy stands of fuchsia. Mistletoe recruitment plots, FBI and 20x20m plots were measured in the Hope this year, and will be measured in the Stafford valley next year. KARAMEA PLACE Planning Resource Consents received, Regional and District Plans, Management Planning One resource consent was received for in-stream drainage works. -

Franz Josef Glacier Township

Mt. Tasman Mt. Cook FRANZ JOSEF IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS www.glaciercountry.co.nz EMERGENCY Dial 111 POLICE (Franz Josef) 752 0044 D Franz Josef Health Clinic 752 0700 GLACIER TOWNSHIP Glacier The Visitor Centre at Franz Josef is open 7 days. I After hours information is available at the front I I entrance of the Visitor Centre/DOC offi ce. H Times given are from the start of track and are approximate I 1 A A. GLACIER VALLEY WALK 1 1 hour 20 mins return following the Waiho riverbed 2 20 G B to the glacier terminal. Please heed all signs & barriers. 14 B. SENTINEL ROCK WALK Condon Street 21 C 3 15 24 23 20 mins return. A steady climb for views of the glacier. 5 4 Cron Street 16 C. DOUGLAS WALK/PETERS POOL 25 22 43 42 12 26 20 mins return to Peter’s Pool for a fantastic 13 9 6 31 GLACIER E refl ective view up the glacier valley. 1 hour loop. 11 7 17 30 27 45 44 10 9 8 Street Cowan 29 28 ACCESS ROAD F D. ROBERTS POINT TRACK 18 33 32 Franz Josef 5 hours return. Climb via a rocky track and 35 33 State Highway 6 J Glacier Lake Wallace St Wallace 34 19 Wombat swingbridges to a high viewpoint above glacier. 40 37 36 Bus township to E. LAKE WOMBAT TRACK 41 39 38 Stop glacier carpark 40 State Highway 6 1 hour 30mins return. Easy forest walk to small refl ective pond. 46 is 5 km 2 hour F.