Annex B: Socio-Economic Conditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pendampingan Kampung Pendidikan Sebagai Upaya Menciptakan Kampung Ramah Anak Di Banyu Urip Wetan Surabaya

KREANOVA : Jurnal Kreativitas dan Inovasi PENDAMPINGAN KAMPUNG PENDIDIKAN SEBAGAI UPAYA MENCIPTAKAN KAMPUNG RAMAH ANAK DI BANYU URIP WETAN SURABAYA Tegowati Maswar Patuh Priyadi Budiyanto Siti Rokhmi Fuadati [email protected] Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Ekonomi Indonesia (STIESIA) Surabaya ABSTRACT Banyu Urip Wetan Village (BUWET) is one of the target areas of the 2019 KP-KAS (Kampung Arek Suroboyo Educational Village) competition program held by the Surabaya city government and DP5A. The KP-KAS competition program was accompanied by DINPUS, NGOs and academics on the elements of the competition categories namely Kampung Kreatif, Asuh, Belajar, Aman, Sehat, Literasi, Penggerak Pemuda Literasi through socialization, training and mentoring. In the KP-KAS Competition, the Portfolio is obliged to prepare in accordance with the provisions stipulated by the Surabaya City Government. Banyu Urip Wetan Village, Sawahan Subdistrict, Surabaya City, is one of the villages that feels the need for assistance in preparing the 2019 KP-CAS Competition Portfolio. The KP-KAS Competition portfolio is in accordance with the provisions and on time and is able to reveal the potential and advantages possessed. The assistance method is to provide technical guidance on the preparation of the KP-KAS Portfolio which is carried out coordinatively by the STIESIA lecturer team in each competition category. The implementation of the KP-KAS competition program through coordination, mutual cooperation and collaboration between RT, RW, parents, children, community leaders and community participation of RW VI greatly helped the implementation of the KP-KAS program. It is recommended to maintain the village environment after the competition and the need to increase cooperation with various parties in protecting children. -

Birds of Gunung Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia: Effects of Altitude, the 1815 Cataclysmic Volcanic Eruption and Trade

FORKTAIL 18 (2002): 49–61 Birds of Gunung Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia: effects of altitude, the 1815 cataclysmic volcanic eruption and trade COLIN R. TRAINOR In June-July 2000, a 10-day avifaunal survey on Gunung Tambora (2,850 m, site of the greatest volcanic eruption in recorded history), revealed an extraordinary mountain with a rather ordinary Sumbawan avifauna: low in total species number, with all species except two oriental montane specialists (Sunda Bush Warbler Cettia vulcania and Lesser Shortwing Brachypteryx leucophrys) occurring widely elsewhere on Sumbawa. Only 11 of 19 restricted-range bird species known for Sumbawa were recorded, with several exceptional absences speculated to result from the eruption. These included: Flores Green Pigeon Treron floris, Russet-capped Tesia Tesia everetti, Bare-throated Whistler Pachycephala nudigula, Flame-breasted Sunbird Nectarinia solaris, Yellow-browed White- eye Lophozosterops superciliaris and Scaly-crowned Honeyeater Lichmera lombokia. All 11 resticted- range species occurred at 1,200-1,600 m, and ten were found above 1,600 m, highlighting the conservation significance of hill and montane habitat. Populations of the Yellow-crested Cockatoo Cacatua sulphurea, Hill Myna Gracula religiosa, Chestnut-backed Thrush Zoothera dohertyi and Chestnut-capped Thrush Zoothera interpres have been greatly reduced by bird trade and hunting in the Tambora Important Bird Area, as has occurred through much of Nusa Tenggara. ‘in its fury, the eruption spared, of the inhabitants, not a although in other places some vegetation had re- single person, of the fauna, not a worm, of the flora, not a established (Vetter 1820 quoted in de Jong Boers 1995). blade of grass’ Francis (1831) in de Jong Boers (1995), Nine years after the eruption the former kingdoms of referring to the 1815 Tambora eruption. -

The Role of Local Leadership in Village Governance

3009 Talent Development & Excellence Vol.12, No.3s, 2020, 3009 – 3020 A Study of Leadership in the Management of Village Development Program: The Role of Local Leadership in Village Governance Kushandajani1,*, Teguh Yuwono2, Fitriyah2 1 Department of Politics and Government, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Diponegoro, Tembalang, Semarang, Jawa Tengah 50271, Indonesia email: [email protected] 2 Department of Politics and Government, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Diponegoro, Tembalang, Semarang, Jawa Tengah 50271, Indonesia Abstract: Policies regarding villages in Indonesia have a strong impact on village governance. Indonesian Law No. 6/2014 recognizes that the “Village has the rights of origin and traditional rights to regulate and manage the interests of the local community.” Through this authority, the village seeks to manage development programs that demand a prominent leadership role for the village leader. For that reason, the research sought to describe the expectations of the village head and measure the reality of their leadership role in managing the development programs in his village. Using a mixed method combining in-depth interview techniques and surveys of some 201 respondents, this research resulted in several important findings. First, Lurah as a village leader was able to formulate the plan very well through the involvement of all village actors. Second, Lurah maintained a strong level of leadership at the program implementation stage, through techniques that built mutual awareness of the importance of village development programs that had been jointly initiated. Keywords: local leadership, village governance, program management I. INTRODUCTION In the hierarchical system of government in Indonesia, the desa (village) is located below the kecamatan (district). -

FORUM MASYARAKAT ADAT DATARAN TINGGI BORNEO (FORMADAT) Borneo (Indonesia & Malaysia)

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. FORUM MASYARAKAT ADAT DATARAN TINGGI BORNEO (FORMADAT) Borneo (Indonesia & Malaysia) Equator Initiative Case Studies Local sustainable development solutions for people, nature, and resilient communities UNDP EQUATOR INITIATIVE CASE STUDY SERIES Local and indigenous communities across the world are 126 countries, the winners were recognized for their advancing innovative sustainable development solutions achievements at a prize ceremony held in conjunction that work for people and for nature. Few publications with the United Nations Convention on Climate Change or case studies tell the full story of how such initiatives (COP21) in Paris. Special emphasis was placed on the evolve, the breadth of their impacts, or how they change protection, restoration, and sustainable management over time. Fewer still have undertaken to tell these stories of forests; securing and protecting rights to communal with community practitioners themselves guiding the lands, territories, and natural resources; community- narrative. The Equator Initiative aims to fill that gap. based adaptation to climate change; and activism for The Equator Initiative, supported by generous funding environmental justice. The following case study is one in from the Government of Norway, awarded the Equator a growing series that describes vetted and peer-reviewed Prize 2015 to 21 outstanding local community and best practices intended to inspire the policy dialogue indigenous peoples initiatives to reduce poverty, protect needed to take local success to scale, to improve the global nature, and strengthen resilience in the face of climate knowledge base on local environment and development change. Selected from 1,461 nominations from across solutions, and to serve as models for replication. -

SUSTAINING SYNERGY, SPREADING ENERGY Themes

Sustainability Report 2018 2018 SUSTAINING SYNERGY, SPREADING ENERGY THEMES SUSTAINING SYNERGY, SPREADING ENERGY PT Pertamina (Persero) has a vital Strengthening synergy has become responsibility to fulfill the demand of energy increasingly meaningful considering the vast in Indonesia. In fact, the demand of energy, areas Pertamina must serve, some of which both fuel oil and gas, continues to increase are difficult to reach because they are in the in line with the increasing population and 3T (frontier, outermost and least developed) vehicles in this country. In order to perform regions and remote areas. Specifically for such responsibility as outstandingly as these regions, Pertamina has been assigned possible, the Company is committed to to distribute fuel through the One-Price Fuel strengthen and maintain the synergy that Program. As a responsible corporation, the has been built, either the synergy amongst Company is strongly committed to making its units, subsidiaries, and amongst SOEs. the assignment successfull. Until the end of 2018, Pertamina has achieved the target set by the government so that the distribution of energy is more evenly distributed and reaches out to all corners of the country. Laporan Keberlanjutan 2018 2 PT Pertamina(Persero) SUSTAINING SYNERGY, SPREADING ENERGY 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Economic Performance Company Profile Environmental Performance Corporate Governance Social Performance 2 Themes 12 About this Sustainability Report 4 Table of Contents 14 Process to Define Report Topics 6 Sustainability -

Indonesia's Transformation and the Stability of Southeast Asia

INDONESIA’S TRANSFORMATION and the Stability of Southeast Asia Angel Rabasa • Peter Chalk Prepared for the United States Air Force Approved for public release; distribution unlimited ProjectR AIR FORCE The research reported here was sponsored by the United States Air Force under Contract F49642-01-C-0003. Further information may be obtained from the Strategic Planning Division, Directorate of Plans, Hq USAF. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rabasa, Angel. Indonesia’s transformation and the stability of Southeast Asia / Angel Rabasa, Peter Chalk. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. “MR-1344.” ISBN 0-8330-3006-X 1. National security—Indonesia. 2. Indonesia—Strategic aspects. 3. Indonesia— Politics and government—1998– 4. Asia, Southeastern—Strategic aspects. 5. National security—Asia, Southeastern. I. Chalk, Peter. II. Title. UA853.I5 R33 2001 959.804—dc21 2001031904 Cover Photograph: Moslem Indonesians shout “Allahu Akbar” (God is Great) as they demonstrate in front of the National Commission of Human Rights in Jakarta, 10 January 2000. Courtesy of AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE (AFP) PHOTO/Dimas. RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. Cover design by Maritta Tapanainen © Copyright 2001 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, -

Tbi Kalimantan 6.Pdf

Forest Products and Local Forest Management in West Kalimantan, Indonesia: Implications for Conservation and Development ISBN 90-5113-056-2 ISSN 1383-6811 © 2002 Tropenbos International The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Tropenbos International No part of this publication, apart from bibliographic data and brief quotations in critical reviews, may be reproduced, re-recorded or published in any form including print photocopy, microform, electronic or electromagnetic record without written permission. Cover photo (inset) : Dayaks in East Kalimantan (Wil de Jong) Printed by : Ponsen en Looijen BV, Wageningen, the Netherlands FOREST PRODUCTS AND LOCAL FOREST MANAGEMENT IN WEST KALIMANTAN, INDONESIA: IMPLICATIONS FOR CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT Wil de Jong Tropenbos International Wageningen, the Netherlands 2002 Tropenbos Kalimantan Series The Tropenbos Kalimantan Series present the results of studies and research activities related to sustainable use and conservation of forest resources in Indonesia. The multi-disciplinary MOF-Tropenbos Kalimantan Programme operates within the framework of Tropenbos International. Executing Indonesian agency is the Forestry Research Institute Samarinda (FRIS), governed by the Forestry Research and Development Agency (FORDA) of the Ministry of Forestry (MOF) Tropenbos International Wageningen The Netherlands Ministry of Forestry Indonesia Centre for International Forest Research Bogor Indonesia ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The field research that lead to this volume was funded by Tropenbos International and by the Rainforest Alliance through their Kleinhans Fellowship. While conducting the fieldwork, between 1992 and 1995, the author was a Research Associate at the New York Botanical Garden’s Institute for Economic Botany. The research was made possible through the Tanjungpura University, Pontianak, and the Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia. -

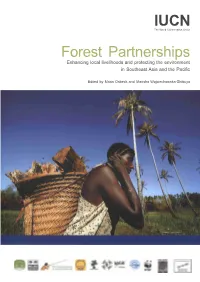

Forest Partnerships Enhancing Local Livelihoods and Protecting the Environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific

IUCN The World Conservation Union Forest Partnerships Enhancing local livelihoods and protecting the environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Edited by Maria Osbeck and Marisha Wojciechowska-Shibuya IUCN The World Conservation Union The designation of geographical entities in this report, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: The World Conservation Union (IUCN), Asia Regional Office Copyright: © 2007 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Osbeck, M., Wojciechowska-Shibuya, M. (Eds) (2007). Forest Partnerships. Enhancing local livelihoods and protecting the environment in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. IUCN, Bangkok, Thailand. 48pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1011-2 Cover design by: IUCN Asia Regional Office Cover photos: Local people, Papua New Guinea. A woman transports a basketful of baked sago from a pit oven back to Rhoku village. Sago is a common subsistence crop in Papua New Guinea. Western Province, Papua New Guinea. December 2004 CREDIT: © Brent Stirton / Getty Images / WWF-UK Layout by: Michael Dougherty Produced by: IUCN Asia Regional Office Printed by: Clung Wicha Press Co., Ltd. -

Experience from Indonesia on the Rabies Introduction Emergency

Ministry Of Agriculture Directorat General of Livestock and Animal Health Bangkok, 27 August 2019 http://ditjennak.pertanian.go.id/ Email : [email protected] Data Sampai tanggal 19 Januari 2019 • Ministry Of Agriculture (MoA) • Ministry Of Public Health (MoH) • Laboratory Denpasar (DIC Denpasar) • Departemen of Husbandary NTB Province • Departemen of Public Health A dog used as guardian of gardens ~ • Dogs use for hunting • Animal movement • The entry of a dog that accompanies traditional fishers Jalur Flores (Labuan Bajo)-Sumbawa (Dompu) Many Iegal Port without Quarantine Jalur Bali (Padang Bai)-Sumbawa (Dompu) Number of Population Rabies animal is known Information about Threat and Rabies Danger isnt known The owner of Animal isn’t responsible Vaccination Movement Dog from Endemis area , to Sumbawa Island, example from Bali and NTT Elimination which animal welfare • Training for vaccinator and Dog catcher →60 officers (Dompu, sumbawa, Bima dan Propinsi) • Training for Laboratory, → 15 officer Capacity • Training for disease investigation Building • The dog population training → 30 officer Human Resouces • Distribution vaccine and operational for vaccination • Dompu Vaccine & • Sumbawa Operasional • Bima •Est.pop: 10,334 •R.Vaccination: 6.165 Dompu •Doses of Vaccines: 9.000 •Human Resources: 40 persons •Est.pop: 36,671 Sumba •R.Vaccination: 2.210 •Doses of vaccine: 3.000 wa •Human Resources: 12 persons •Est.pop:16.100 •R.Vaccination: 1.503 Bima •Doses of Vaksin: 2000 •SDM :10 petugas Socialization for Community, figure public -

Fungsi Pembinaan Lurah Terhadap Rukun Tetangga Dan Rukun Warga Di Kelurahan Tangkerang Tengah Kecamatan Marpoyan Damai Kota Pekanbaru Tahun 2013-2014

FUNGSI PEMBINAAN LURAH TERHADAP RUKUN TETANGGA DAN RUKUN WARGA DI KELURAHAN TANGKERANG TENGAH KECAMATAN MARPOYAN DAMAI KOTA PEKANBARU TAHUN 2013-2014 Ichwann Hastona Email : [email protected] Pembimbing : Drs. H. Muhammad Ridwan Jurusan Ilmu Pemerintahan Fakultas Ilmu Sosial Dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Riau Program Studi Ilmu Pemerintahan FISIP Universitas Riau Kampus bina widya jl. H.R. Soebrantas Km. 12,5 Simp. Baru Pekanbaru 28293- Telp/Fax. 0761-63277 ABSTRACT The chief role is very important in a region, especially for the community, Based on Government Regulation Number 73 Year 2005 about Ward article 5 , one of the main tasks village that is doing construction of a society that is RW and RT. The existence of his neighbor community and Pillars of the (RW) have a strategic role, especially as a partner in the event district government affairs, development and community affairs. What about the function headman to the village of his neighbor and Pillars of residents in the village Tangkerang among sub-district Marpoyan Peace Pekanbaru in 2013-2014? Research method that is applied in this study is descriptive qualitative analysis method that is trying to present based on the phenomena that are and to all the facts related to problems that were discussed, namely to know the construction of the village of Pillars of neighbors and Pillars of residents in the village Tangkerang among sub-district Marpoyan Peace Pekanbaru in 2013- 2014. Results of the study showed fungsi construction of the village of Pillars of neighbors and Pillars of residents In the village Tangkerang among sub-district Marpoyan Peace Pekanbaru in 2013-2014 according to the writer is not optimal done with good, where construction of the village in the planning community institutional village RW and RT is in line with what was planned, however, RW on the development of organization and RT did not give administration report regularly to the chief, so that the chief did not carry out the supervision institutional village community RW and RT. -

Chapter 4 Village Level Socio-Political Context

Chapter 4 Village Level Socio-Political Context 4.1 Introduction The following general overview of the socio-political context in rural, coastal villages of central Maluku is based on the results of six case studies carried out on Saparua, Haruku and Ambon Islands. All study sites are Christian villages. Therefore some of the findings, especially the role of the church in society, do not pertain to the social structure in Muslim villages. Although a dominant force, the formal village government is only one of three key elements generally recognized in Maluku villages. These three key institutions are called the Tiga Tungku, or three hearthstones: the government, the church (or in Muslim villages, the mosque) and adat or traditional authorities. In some villages, teachers are also important and may displace adat leaders in the Tiga Tungku. 4.2 Traditional Village Government Structure Prior to the enactment of the local government law (Law No. 5, 1979), villages in Maluku were led by a hereditary chief or raja. Although now considered part of the “traditional” structure, the position of raja was in fact not part of the indigenous adat social structure, but a construction of the Dutch colonial leaders. When the Dutch consolidated their power in Maluku and forced the hill-dwelling people to settle in coastal villages, they appointed the village leader, i.e., the raja. Previous to this, the clan groups living in the hills were led by warrior chiefs (kapitan). The raja governed together with administrative and legislative councils (saniri) whose members were the clan leaders. The raja’s powers under this system were not absolute. -

Legalization Instructions | the Netherlands

Legalization instructions | the Netherlands As part of your immigration procedure for the Netherlands, your legal certificates need to be acknowledged by the Dutch authorities. Therefore, your legal certificates may need to be: • Re-issued; and/or • Translated to another language; and/or • Legalized Depending on the issuing country, the process to legalize certificates differs. On the next page, you can click on the country where the legal certificate originates from to find the legalization instructions. In case your certificate(s) originate from various countries, you will have to follow the relevant legalization instructions. At the bottom of each legalization instruction, you can click on ’back to top’ to return to the frontpage and thereafter scroll down to the index page to select another legalization instruction. We strongly advise you to start the legalization process as soon as possible, as it can be lengthy. Once the legalized certificates are available to you, share a scanned copy hereof with Deloitte so we can verify if the documents meet the conditions for use in the Netherlands. Certificate issuing countries Argentina Ireland Slovenia Australia Israel South Africa Austria Italy South Korea Belarus Japan Spain Belgium Jordan Sri Lanka Brazil Latvia Sweden Bulgaria Lebanon Switzerland Cambodia Lithuania Syria Canada Luxembourg Taiwan Chile Malaysia Thailand China Malta The Philippines Colombia Mexico Turkey Costa Rica Moldova Uganda Croatia Morocco Ukraine Cyprus Nepal United Kingdom Czech Republic New Zealand Uruguay Denmark Nigeria United States of America Dominican Republic Norway Uzbekistan Ecuador Pakistan Venezuela Egypt Panama Vietnam Estonia Paraguay Finland Peru France Poland Germany Portugal Greece Romania Hungary Russian Federation India Saudi Arabia Indonesia Serbia Iran Singapore Iraq Slovakia Reach out to your Deloitte immigration advisor if the issuing country of the certificate is not listed above.