Logical Consequence and Logical Expressions*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dialetheists' Lies About the Liar

PRINCIPIA 22(1): 59–85 (2018) doi: 10.5007/1808-1711.2018v22n1p59 Published by NEL — Epistemology and Logic Research Group, Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), Brazil. DIALETHEISTS’LIES ABOUT THE LIAR JONAS R. BECKER ARENHART Departamento de Filosofia, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, BRAZIL [email protected] EDERSON SAFRA MELO Departamento de Filosofia, Universidade Federal do Maranhão, BRAZIL [email protected] Abstract. Liar-like paradoxes are typically arguments that, by using very intuitive resources of natural language, end up in contradiction. Consistent solutions to those paradoxes usually have difficulties either because they restrict the expressive power of the language, orelse because they fall prey to extended versions of the paradox. Dialetheists, like Graham Priest, propose that we should take the Liar at face value and accept the contradictory conclusion as true. A logical treatment of such contradictions is also put forward, with the Logic of Para- dox (LP), which should account for the manifestations of the Liar. In this paper we shall argue that such a formal approach, as advanced by Priest, is unsatisfactory. In order to make contradictions acceptable, Priest has to distinguish between two kinds of contradictions, in- ternal and external, corresponding, respectively, to the conclusions of the simple and of the extended Liar. Given that, we argue that while the natural interpretation of LP was intended to account for true and false sentences, dealing with internal contradictions, it lacks the re- sources to tame external contradictions. Also, the negation sign of LP is unable to represent internal contradictions adequately, precisely because of its allowance of sentences that may be true and false. -

Logical Truth, Contradictions, Inconsistency, and Logical Equivalence

Logical Truth, Contradictions, Inconsistency, and Logical Equivalence Logical Truth • The semantical concepts of logical truth, contradiction, inconsistency, and logi- cal equivalence in Predicate Logic are straightforward adaptations of the corre- sponding concepts in Sentence Logic. • A closed sentence X of Predicate Logic is logically true, X, if and only if X is true in all interpretations. • The logical truth of a sentence is proved directly using general reasoning in se- mantics. • Given soundness, one can also prove the logical truth of a sentence X by provid- ing a derivation with no premises. • The result of the derivation is that X is theorem, ` X. An Example • (∀x)Fx ⊃ (∃x)Fx. – Suppose d satisfies ‘(∀x)Fx’. – Then all x-variants of d satisfy ‘Fx’. – Since the domain D is non-empty, some x-variant of d satisfies ‘Fx’. – So d satisfies ‘(∃x)Fx’ – Therefore d satisfies ‘(∀x)Fx ⊃ (∃x)Fx’, QED. • ` (∀x)Fx ⊃ (∃x)Fx. 1 (∀x)Fx P 2 Fa 1 ∀ E 3 (∃x)Fx 1 ∃ I Contradictions • A closed sentence X of Predicate Logic is a contradiction if and only if X is false in all interpretations. • A sentence X is false in all interpretations if and only if its negation ∼X is true on all interpretations. • Therefore, one may directly demonstrate that a sentence is a contradiction by proving that its negation is a logical truth. • If the ∼X of a sentence is a logical truth, then given completeness, it is a theorem, and hence ∼X can be derived from no premises. 1 • If a sentence X is such that if it is true in any interpretation, both Y and ∼Y are true in that interpretation, then X cannot be true on any interpretation. -

Pluralisms About Truth and Logic Nathan Kellen University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 8-9-2019 Pluralisms about Truth and Logic Nathan Kellen University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Kellen, Nathan, "Pluralisms about Truth and Logic" (2019). Doctoral Dissertations. 2263. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/2263 Pluralisms about Truth and Logic Nathan Kellen, PhD University of Connecticut, 2019 Abstract: In this dissertation I analyze two theories, truth pluralism and logical pluralism, as well as the theoretical connections between them, including whether they can be combined into a single, coherent framework. I begin by arguing that truth pluralism is a combination of realist and anti-realist intuitions, and that we should recognize these motivations when categorizing and formulating truth pluralist views. I then introduce logical functionalism, which analyzes logical consequence as a functional concept. I show how one can both build theories from the ground up and analyze existing views within the functionalist framework. One upshot of logical functionalism is a unified account of logical monism, pluralism and nihilism. I conclude with two negative arguments. First, I argue that the most prominent form of logical pluralism faces a serious dilemma: it either must give up on one of the core principles of logical consequence, and thus fail to be a theory of logic at all, or it must give up on pluralism itself. I call this \The Normative Problem for Logical Pluralism", and argue that it is unsolvable for the most prominent form of logical pluralism. Second, I examine an argument given by multiple truth pluralists that purports to show that truth pluralists must also be logical pluralists. -

The Validities of Pep and Some Characteristic Formulas in Modal Logic

THE VALIDITIES OF PEP AND SOME CHARACTERISTIC FORMULAS IN MODAL LOGIC Hong Zhang, Huacan He School of Computer Science, Northwestern Polytechnical University,Xi'an, Shaanxi 710032, P.R. China Abstract: In this paper, we discuss the relationships between some characteristic formulas in normal modal logic with their frames. We find that the validities of the modal formulas are conditional even though some of them are intuitively valid. Finally, we prove the validities of two formulas of Position- Exchange-Principle (PEP) proposed by papers 1 to 3 by using of modal logic and Kripke's semantics of possible worlds. Key words: Characteristic Formulas, Validity, PEP, Frame 1. INTRODUCTION Reasoning about knowledge and belief is an important issue in the research of multi-agent systems, and reasoning, which is set up from the main ideas of situational calculus, about other agents' states and actions is one of the most important directions in Al^^'^\ Papers [1-3] put forward an axiom scheme in reasoning about others(RAO) in multi-agent systems, and a rule called Position-Exchange-Principle (PEP), which is shown as following, was abstracted . C{(p^y/)^{C(p->Cy/) (Ce{5f',...,5f-}) When the length of C is at least 2, it reflects the mechanism of an agent reasoning about knowledge of others. For example, if C is replaced with Bf B^/, then it should be B':'B]'{(p^y/)-^iBf'B]'(p^Bf'B]'y/) 872 Hong Zhang, Huacan He The axiom schema plays a useful role as that of modus ponens and axiom K when simplifying proof. Though examples were demonstrated as proofs in papers [1-3], from the perspectives both in semantics and in syntax, the rule is not so compellent. -

The Analytic-Synthetic Distinction and the Classical Model of Science: Kant, Bolzano and Frege

Synthese (2010) 174:237–261 DOI 10.1007/s11229-008-9420-9 The analytic-synthetic distinction and the classical model of science: Kant, Bolzano and Frege Willem R. de Jong Received: 10 April 2007 / Revised: 24 July 2007 / Accepted: 1 April 2008 / Published online: 8 November 2008 © The Author(s) 2008. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This paper concentrates on some aspects of the history of the analytic- synthetic distinction from Kant to Bolzano and Frege. This history evinces con- siderable continuity but also some important discontinuities. The analytic-synthetic distinction has to be seen in the first place in relation to a science, i.e. an ordered system of cognition. Looking especially to the place and role of logic it will be argued that Kant, Bolzano and Frege each developed the analytic-synthetic distinction within the same conception of scientific rationality, that is, within the Classical Model of Science: scientific knowledge as cognitio ex principiis. But as we will see, the way the distinction between analytic and synthetic judgments or propositions functions within this model turns out to differ considerably between them. Keywords Analytic-synthetic · Science · Logic · Kant · Bolzano · Frege 1 Introduction As is well known, the critical Kant is the first to apply the analytic-synthetic distinction to such things as judgments, sentences or propositions. For Kant this distinction is not only important in his repudiation of traditional, so-called dogmatic, metaphysics, but it is also crucial in his inquiry into (the possibility of) metaphysics as a rational science. Namely, this distinction should be “indispensable with regard to the critique of human understanding, and therefore deserves to be classical in it” (Kant 1783, p. -

The Substitutional Analysis of Logical Consequence

THE SUBSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS OF LOGICAL CONSEQUENCE Volker Halbach∗ dra version ⋅ please don’t quote ónd June óþÕä Consequentia ‘formalis’ vocatur quae in omnibus terminis valet retenta forma consimili. Vel si vis expresse loqui de vi sermonis, consequentia formalis est cui omnis propositio similis in forma quae formaretur esset bona consequentia [...] Iohannes Buridanus, Tractatus de Consequentiis (Hubien ÕÉßä, .ì, p.óóf) Zf«±§Zh± A substitutional account of logical truth and consequence is developed and defended. Roughly, a substitution instance of a sentence is dened to be the result of uniformly substituting nonlogical expressions in the sentence with expressions of the same grammatical category. In particular atomic formulae can be replaced with any formulae containing. e denition of logical truth is then as follows: A sentence is logically true i all its substitution instances are always satised. Logical consequence is dened analogously. e substitutional denition of validity is put forward as a conceptual analysis of logical validity at least for suciently rich rst-order settings. In Kreisel’s squeezing argument the formal notion of substitutional validity naturally slots in to the place of informal intuitive validity. ∗I am grateful to Beau Mount, Albert Visser, and Timothy Williamson for discussions about the themes of this paper. Õ §Z êZo±í At the origin of logic is the observation that arguments sharing certain forms never have true premisses and a false conclusion. Similarly, all sentences of certain forms are always true. Arguments and sentences of this kind are for- mally valid. From the outset logicians have been concerned with the study and systematization of these arguments, sentences and their forms. -

Propositional Logic (PDF)

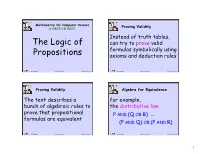

Mathematics for Computer Science Proving Validity 6.042J/18.062J Instead of truth tables, The Logic of can try to prove valid formulas symbolically using Propositions axioms and deduction rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.1 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.2 Proving Validity Algebra for Equivalence The text describes a for example, bunch of algebraic rules to the distributive law prove that propositional P AND (Q OR R) ≡ formulas are equivalent (P AND Q) OR (P AND R) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.3 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.4 1 Algebra for Equivalence Algebra for Equivalence for example, The set of rules for ≡ in DeMorgan’s law the text are complete: ≡ NOT(P AND Q) ≡ if two formulas are , these rules can prove it. NOT(P) OR NOT(Q) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.5 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.6 A Proof System A Proof System Another approach is to Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a start with some valid particularly elegant example of this idea. formulas (axioms) and deduce more valid formulas using proof rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.7 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.8 2 A Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a Axioms: particularly elegant example of 1) (¬P → P) → P this idea. It covers formulas 2) P → (¬P → Q) whose only logical operators are 3) (P → Q) → ((Q → R) → (P → R)) IMPLIES (→) and NOT. The only rule: modus ponens Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.9 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.10 Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Prove formulas by starting with Prove formulas by starting with axioms and repeatedly applying axioms and repeatedly applying the inference rule. -

Yuji NISHIYAMA in This Article We Shall Focus Our Attention Upon

The Notion of Presupposition* Yuji NISHIYAMA Keio University In this article we shall focus our attention upon the clarificationof the notion of presupposition;First, we shall be concerned with what kind of notion is best understood as the proper notion of presupposition that grammars of natural languageshould deal with. In this connection,we shall defend "logicalpresupposi tion". Second, we shall consider how to specify the range of X and Y in the presuppositionformula "X presupposes Y". Third, we shall discuss several difficultieswith the standard definition of logical presupposition. In connection with this, we shall propose a clear distinction between "the definition of presupposi tion" and "the rule of presupposition". 1. The logical notion of presupposition What is a presupposition? Or, more particularly, what is the alleged result of a presupposition failure? In spite of the attention given to it, this question can hardly be said to have been settled. Various answers have been suggested by the various authors: inappropriate use of a sentence, failure to perform an illocutionary act, anomaly, ungrammaticality, unintelligibility, infelicity, lack of truth value-each has its advocates. Some of the apparent disagreementmay be only a notational and terminological, but other disagreement raises real, empirically significant, theoretical questions regarding the relationship between logic and language. However, it is not the aim of this article to straighten out the various proposals about the concept of presupposition. Rather, we will be concerned with one notion of presupposition,which stems from Frege (1892)and Strawson (1952),that is: (1) presupposition is a condition under which a sentence expressing an assertive proposition can be used to make a statement (or can bear a truth value)1 We shall call this notion of presupposition "the statementhood condition" or "the conditionfor bivalence". -

Plurals and Mereology

Journal of Philosophical Logic (2021) 50:415–445 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10992-020-09570-9 Plurals and Mereology Salvatore Florio1 · David Nicolas2 Received: 2 August 2019 / Accepted: 5 August 2020 / Published online: 26 October 2020 © The Author(s) 2020 Abstract In linguistics, the dominant approach to the semantics of plurals appeals to mere- ology. However, this approach has received strong criticisms from philosophical logicians who subscribe to an alternative framework based on plural logic. In the first part of the article, we offer a precise characterization of the mereological approach and the semantic background in which the debate can be meaningfully reconstructed. In the second part, we deal with the criticisms and assess their logical, linguistic, and philosophical significance. We identify four main objections and show how each can be addressed. Finally, we compare the strengths and shortcomings of the mereologi- cal approach and plural logic. Our conclusion is that the former remains a viable and well-motivated framework for the analysis of plurals. Keywords Mass nouns · Mereology · Model theory · Natural language semantics · Ontological commitment · Plural logic · Plurals · Russell’s paradox · Truth theory 1 Introduction A prominent tradition in linguistic semantics analyzes plurals by appealing to mere- ology (e.g. Link [40, 41], Landman [32, 34], Gillon [20], Moltmann [50], Krifka [30], Bale and Barner [2], Chierchia [12], Sutton and Filip [76], and Champollion [9]).1 1The historical roots of this tradition include Leonard and Goodman [38], Goodman and Quine [22], Massey [46], and Sharvy [74]. Salvatore Florio [email protected] David Nicolas [email protected] 1 Department of Philosophy, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom 2 Institut Jean Nicod, Departement´ d’etudes´ cognitives, ENS, EHESS, CNRS, PSL University, Paris, France 416 S. -

A Validity Framework for the Use and Development of Exported Assessments

A Validity Framework for the Use and Development of Exported Assessments By María Elena Oliveri, René Lawless, and John W. Young A Validity Framework for the Use and Development of Exported Assessments María Elena Oliveri, René Lawless, and John W. Young1 1 The authors would like to acknowledge Bob Mislevy, Michael Kane, Kadriye Ercikan, and Maurice Hauck for their valuable input and expertise in reviewing various iterations of the framework as well as Priya Kannan, Don Powers, and James Carlson for their input throughout the technical review process. Copyright © 2015 Educational Testing Service. All Rights Reserved. ETS, the ETS logo, GRADUATE RECORD EXAMINATIONS, GRE, LISTENTING. LEARNING. LEADING, TOEIC, and TOEFL are registered trademarks of Educational Testing Service (ETS). EXADEP and EXAMEN DE ADMISIÓN A ESTUDIOS DE POSGRADO are trademarks of ETS. 1 Abstract In this document, we present a framework that outlines the key considerations relevant to the fair development and use of exported assessments. Exported assessments are developed in one country and are used in countries with a population that differs from the one for which the assessment was developed. Examples of these assessments include the Graduate Record Examinations® (GRE®) and el Examen de Admisión a Estudios de Posgrado™ (EXADEP™), among others. Exported assessments can be used to make inferences about performance in the exporting country or in the receiving country. To illustrate, the GRE can be administered in India and be used to predict success at a graduate school in the United States, or similarly it can be administered in India to predict success in graduate school at a graduate school in India. -

The Development of Mathematical Logic from Russell to Tarski: 1900–1935

The Development of Mathematical Logic from Russell to Tarski: 1900–1935 Paolo Mancosu Richard Zach Calixto Badesa The Development of Mathematical Logic from Russell to Tarski: 1900–1935 Paolo Mancosu (University of California, Berkeley) Richard Zach (University of Calgary) Calixto Badesa (Universitat de Barcelona) Final Draft—May 2004 To appear in: Leila Haaparanta, ed., The Development of Modern Logic. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004 Contents Contents i Introduction 1 1 Itinerary I: Metatheoretical Properties of Axiomatic Systems 3 1.1 Introduction . 3 1.2 Peano’s school on the logical structure of theories . 4 1.3 Hilbert on axiomatization . 8 1.4 Completeness and categoricity in the work of Veblen and Huntington . 10 1.5 Truth in a structure . 12 2 Itinerary II: Bertrand Russell’s Mathematical Logic 15 2.1 From the Paris congress to the Principles of Mathematics 1900–1903 . 15 2.2 Russell and Poincar´e on predicativity . 19 2.3 On Denoting . 21 2.4 Russell’s ramified type theory . 22 2.5 The logic of Principia ......................... 25 2.6 Further developments . 26 3 Itinerary III: Zermelo’s Axiomatization of Set Theory and Re- lated Foundational Issues 29 3.1 The debate on the axiom of choice . 29 3.2 Zermelo’s axiomatization of set theory . 32 3.3 The discussion on the notion of “definit” . 35 3.4 Metatheoretical studies of Zermelo’s axiomatization . 38 4 Itinerary IV: The Theory of Relatives and Lowenheim’s¨ Theorem 41 4.1 Theory of relatives and model theory . 41 4.2 The logic of relatives . -

Logic, Proofs

CHAPTER 1 Logic, Proofs 1.1. Propositions A proposition is a declarative sentence that is either true or false (but not both). For instance, the following are propositions: “Paris is in France” (true), “London is in Denmark” (false), “2 < 4” (true), “4 = 7 (false)”. However the following are not propositions: “what is your name?” (this is a question), “do your homework” (this is a command), “this sentence is false” (neither true nor false), “x is an even number” (it depends on what x represents), “Socrates” (it is not even a sentence). The truth or falsehood of a proposition is called its truth value. 1.1.1. Connectives, Truth Tables. Connectives are used for making compound propositions. The main ones are the following (p and q represent given propositions): Name Represented Meaning Negation p “not p” Conjunction p¬ q “p and q” Disjunction p ∧ q “p or q (or both)” Exclusive Or p ∨ q “either p or q, but not both” Implication p ⊕ q “if p then q” Biconditional p → q “p if and only if q” ↔ The truth value of a compound proposition depends only on the value of its components. Writing F for “false” and T for “true”, we can summarize the meaning of the connectives in the following way: 6 1.1. PROPOSITIONS 7 p q p p q p q p q p q p q T T ¬F T∧ T∨ ⊕F →T ↔T T F F F T T F F F T T F T T T F F F T F F F T T Note that represents a non-exclusive or, i.e., p q is true when any of p, q is true∨ and also when both are true.