Recalling Plums from the Wild

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pru Nus Contains Many Species and Cultivars, Pru Nus Including Both Fruits and Woody Ornamentals

;J. N l\J d.000 A~ :J-6 '. AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION SERVICE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA • The genus Pru nus contains many species and cultivars, Pru nus including both fruits and woody ornamentals. The arboretum's Prunus maacki (Amur Cherry). This small tree has bright, emphasis is on the ornamental plants. brownish-yellow bark that flakes off in papery strips. It is par Prunus americana (American Plum). This small tree furnishes ticularly attractive in winter when the stems contrast with the fruits prized for making preserves and is also an ornamental. snow. The flowers and fruits are produced in drooping racemes In early May, the trees are covered with a "snowball" bloom similar to those of our native chokecherry. This plant is ex of white flowers. If these blooms escape the spring frosts, tremely hardy and well worth growing. there will be a crop of colorful fruits in the fall. The trees Prunus maritima (Beach Plum). This species is native to the sucker freely, and unless controlled, a thicket results. The A coastal plains from Maine to Virginia. It's a sprawling shrub merican Plum is excellent for conservation purposes, and the reaching a height of about 6 feet. It blooms early with small thickets are favorite refuges for birds and wildlife. white flowers. Our plants have shown varying degrees of die Prunus amygdalus (Almond). Several cultivars of almonds back and have been removed for this reason. including 'Halls' and 'Princess'-have been tested. Although Prunus 'Minnesota Purple.' This cultivar was named by the the plants survived and even flowered, each winter's dieback University of Minnesota in 1920. -

Montgomery County Landscape Plant List

9020 Airport Road Conroe, TX 77303 (936) 539-7824 MONTGOMERY COUNTY LANDSCAPE PLANT LIST Scientific Name Common Name Size Habit Light Water Native Wildlife Comments PERENNIALS Abelmoschus ‘Oriental Red’ Hibiscus, Oriental Red 3 x 3 D F L N Root hardy, reseeds Abutilon sp. Flowering Maple Var D F M N Acalypha pendula Firetail Chenille 8" x 8" E P H N Acanthus mollis Bear's Breeches 3 x 3 D S M N Root hardy Acorus gramineus Sweet Flag 1 x 1 E P M N Achillea millefolium var. rosea Yarrow, Pink 2 x 2 E F/P M N BF Butterfly nectar plant Adiantum capillus-veneris Fern, Maidenhair 1 x 1 E P/S H Y Dormant when dry Adiantum hispidulum Fern, Rosy Maidenhair 1 x 1 D S H N Agapanthus africanus Lily of the Nile 2 x 2 E P M N Agastache ‘Black Adder’ Agastache, Black Adder 2 x 2 D F M N BF, HB Butterfly/hummingbird nectar plant Ageratina havanensis Mistflower, Fragrant 3 x 3 D F/P L Y BF Can take poor drainage Ageratina wrightii Mistflower, White 2 x 2 D F/P L Y BF Butterfly nectar plant Ajuga reptans Bugle Flower 6" x 6" E P/S M N Alocasia sp. Taro Var D P M N Aggressive in wet areas Aloysia virgata Almond Verbena 8 x 5 D S L N BF Very fragrant, nectar plant Alpinia sp. Gingers, Shell 6 x 6 E F/P M N Amsonia tabernaemontana Texas Blue Star 3 x 3 D P M Y Can take poor drainage Andropogon gerardii Bluestem, Big 3 to 8 D F/P L Y Andropogon glomeratus Bluestem, Brushy 2 to 5 D F/P L Y Andropogon ternarius Bluestem, Splitbeard 1 to 4 D F/P L Y Anisacanthus wrightii Flame Acanthus 3 x 3 D F L Y HB Hummingbird nectar plant Aquilegia chrysantha Columbine, Yellow 2 x 1 E P/S M Y Dormant when dry, reseeds Aquilegia canadensis Columbine, Red 1 x 1 E P/S M Y Dormant when dry, reseeds Ardisia crenata Ardisia 1 x 1 E P/S M N Ardisia japonica Ardisia 2 x 2 E P/S M N Artemisia sp. -

Plum Crazy: Rediscovering Our Lost Prunus Resources W.R

Plum Crazy: Rediscovering Our Lost Prunus Resources W.R. Okie1 U.S. Department of Agriculture–Agricultural Research Service, Southeastern Fruit and Tree Nut Research Laboratory, 21 Dunbar Road, Byron, GA 31008 Recent utilization of genetic resources of peach [Prunus persica (‘Quetta’ from India, ‘John Rivers’ from England, and ‘Lippiatts’ (L.) Batsch] and Japanese plum (P. salicina Lindl. and hybrids) has from New Zealand) were critical to the development of modern been limited in the United States compared with that of many crops. nectarines in California (Taylor, 1959). However, most fresh-market Difficulties in collection, importation, and quarantine throughput have peach breeding programs in the United States have used germplasm limited the germplasm available. Prunus is more difficult to preserve developed in the United States for cultivar development (Okie, 1998). because more space is needed than for small fruit crops, and the shorter Only in New Jersey was there extensive hybridization with imported life of trees relative to other tree crops because of disease and insect clones, and most of these hybrids have not resulted in named cultivars problems. Lack of suitable rootstocks has also reduced tree life. The (Blake and Edgerton, 1946). trend toward fewer breeding programs, most of which emphasize In recent years, interest in collecting and utilizing novel germplasm “short-term” (long-term compared to most crops) commercial cultivar has increased. For example, non-melting clingstone peaches from development to meet immediate industry needs, has also contributed Mexico and Brazil have been used in the joint USDA–Univ. of to reduced use of exotic material. Georgia–Univ. of Florida breeding program for the development of Probably all modern commercial peaches grown in the United early ripening, non-melting, fresh-market peaches for low-chill areas States are related to ‘Chinese Cling’, a peach imported from China (Beckman and Sherman, 1996). -

Wild Goose Plum Prunus Hortulana ILLINOIS RANGE Tree in Flower

wild goose plum Prunus hortulana Kingdom: Plantae FEATURES Division/Phylum: Magnoliophyta Wild goose plum is a small tree that may attain a Class: Magnoliopsida height of 20 feet and a trunk diameter of eight Order: Rosales inches. Its gray or brown bark becomes scaly at maturity. Twigs are slender, red-brown and smooth. Family: Rosaceae The ovoid, red-brown buds are about one-fourth ILLINOIS STATUS inch in length. Leaves are arranged alternately along the stem. These simple, oblong to oval leaves may common, native be as much as six inches long and two inches wide. Each leaf is finely-toothed along the edges. Each tooth has a gland at its tip. The leaf is green and smooth on the upper surface and pale and sometimes hairy on the lower surface. Flowers develop in clusters, up to one inch wide. The five- petaled, white flowers appear after the leaves are partly grown. The fruit is a drupe (a seed enclosed in a hard, dry material that in turn is covered with a fleshy material). The drupe is nearly spherical and up to one inch in diameter. This red, fleshy fruit is hard, bitter and contains one seed. BEHAVIORS © Guy Sternberg Wild goose plum may be found in the southern one- half of Illinois. It grows in wood edges and thickets. tree in flower Flowers are produced from March through April. The wood is hard and brown. ILLINOIS RANGE © Guy Sternberg flowering branches © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

(Prunus Spp) Using Random Amplified Microsatellite Polymorphism Markers

Assessment of genetic diversity and relationships among wild and cultivated Tunisian plums (Prunus spp) using random amplified microsatellite polymorphism markers H. Ben Tamarzizt, S. Ben Mustapha, G. Baraket, D. Abdallah and A. Salhi-Hannachi Laboratory of Molecular Genetics, Immunology & Biotechnology, Faculty of Sciences of Tunis, University of Tunis El Manar, El Manar, Tunis, Tunisia Corresponding author: A. Salhi-Hannachi E-mail: [email protected] Genet. Mol. Res. 14 (1): 1942-1956 (2015) Received January 8, 2014 Accepted July 8, 2014 Published March 20, 2015 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4238/2015.March.20.4 ABSTRACT. The usefulness of random amplified microsatellite polymorphism markers to study the genetic diversity and relationships among cultivars belonging to Prunus salicina and P. domestica and their wild relatives (P. insititia and P. spinosa) was investigated. A total of 226 of 234 bands were polymorphic (96.58%). The 226 random amplified microsatellite polymorphism markers were screened using 15 random amplified polymorphic DNA and inter-simple sequence repeat primers combinations for 54 Tunisian plum accessions. The percentage of polymorphic bands (96.58%), the resolving power of primers values (135.70), and the polymorphic information content demonstrated the efficiency of the primers used in this study. The genetic distances between accessions ranged from 0.18 to 0.79 with a mean of 0.24, suggesting a high level of genetic diversity at the intra- and interspecific levels. The unweighted pair group with arithmetic mean dendrogram Genetics and Molecular Research 14 (1): 1942-1956 (2015) ©FUNPEC-RP www.funpecrp.com.br Genetic diversity of Tunisian plums using RAMPO markers 1943 and principal component analysis discriminated cultivars efficiently and illustrated relationships and divergence between spontaneous, locally cultivated, and introduced plum types. -

Coastal Landscaping in Massachusetts Plant List

Coastal Landscaping in Massachusetts Plant List This PDF document provides additional information to supplement the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management (CZM) Coastal Landscaping website. The plants listed below are good choices for the rugged coastal conditions of Massachusetts. The Coastal Beach Plant List, Coastal Dune Plant List, and Coastal Bank Plant List give recommended species for each specified location (some species overlap because they thrive in various conditions). Photos and descriptions of selected species can be found on the following pages: • Grasses and Perennials • Shrubs and Groundcovers • Trees CZM recommends using native plants wherever possible. The vast majority of the plants listed below are native (which, for purposes of this fact sheet, means they occur naturally in eastern Massachusetts). Certain non-native species with specific coastal landscaping advantages that are not known to be invasive have also been listed. These plants are labeled “not native,” and their state or country of origin is provided. (See definitions for native plant species and non-native plant species at the end of this fact sheet.) Coastal Beach Plant List Plant List for Sheltered Intertidal Areas Sheltered intertidal areas (between the low-tide and high-tide line) of beach, marsh, and even rocky environments are home to particular plant species that can tolerate extreme fluctuations in water, salinity, and temperature. The following plants are appropriate for these conditions along the Massachusetts coast. Black Grass (Juncus gerardii) native Marsh Elder (Iva frutescens) native Saltmarsh Cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) native Saltmeadow Cordgrass (Spartina patens) native Sea Lavender (Limonium carolinianum or nashii) native Spike Grass (Distichlis spicata) native Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) native Plant List for a Dry Beach Dry beach areas are home to plants that can tolerate wind, wind-blown sand, salt spray, and regular interaction with waves and flood waters. -

Plums on the Prairies by Rick Sawatzky

Plums on the Prairies by Rick Sawatzky Information from Literature Much has been published about pollination, pollinators, pollinizers, fertilization and fruit set in text books and periodicals. The definitions are not difficult. Pollination is the movement of pollen among compatible flowering plants (cross-pollination) or from anthers to stigmas on the same plant or different plants of the same clone (self-pollination). Many plants will self-pollinate but set very few fruit; some authors consider them self- pollinating but they are definitely not self-fruitful. Self-fruitful plants (and clones) set a crop of fruit after self-pollination; some of these plants bear fruit with no seeds (parthenocarpy); others develop seeds with embryos that are genetically identical to the parent plant (apomixis); and others produce haploid seeds that develop from an unfertilized egg cell. (When haploid seeds germinate they are very weak seedlings with only half the chromosomes of normal seedlings.) Regarding temperate zone tree fruits, self-pollination and fruit set does not mean self-fertility and the development of normal seeds. Many temperate zone small fruit species (e.g. strawberries and raspberries) are self-fertile and develop maximum yields of fruit with normal seeds as the result of self-pollination by insects. Pollinators, usually insects, are vectors of pollen movement. Pollinizers are plants which provide the appropriate pollen for other plants. Fertilization is the process in which gametes from the pollen unite with egg cells in the ovary of the flower. Normal seeds are usually the result of this process. Also, the principles are easily understood. Poor fertilization in plums and other Prunus species results in a poor fruit set. -

Checklist of Illinois Native Trees

Technical Forestry Bulletin · NRES-102 Checklist of Illinois Native Trees Jay C. Hayek, Extension Forestry Specialist Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Sciences Updated May 2019 This Technical Forestry Bulletin serves as a checklist of Tree species prevalence (Table 2), or commonness, and Illinois native trees, both angiosperms (hardwoods) and gym- county distribution generally follows Iverson et al. (1989) and nosperms (conifers). Nearly every species listed in the fol- Mohlenbrock (2002). Additional sources of data with respect lowing tables† attains tree-sized stature, which is generally to species prevalence and county distribution include Mohlen- defined as having a(i) single stem with a trunk diameter brock and Ladd (1978), INHS (2011), and USDA’s The Plant Da- greater than or equal to 3 inches, measured at 4.5 feet above tabase (2012). ground level, (ii) well-defined crown of foliage, and(iii) total vertical height greater than or equal to 13 feet (Little 1979). Table 2. Species prevalence (Source: Iverson et al. 1989). Based on currently accepted nomenclature and excluding most minor varieties and all nothospecies, or hybrids, there Common — widely distributed with high abundance. are approximately 184± known native trees and tree-sized Occasional — common in localized patches. shrubs found in Illinois (Table 1). Uncommon — localized distribution or sparse. Rare — rarely found and sparse. Nomenclature used throughout this bulletin follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System —the ITIS data- Basic highlights of this tree checklist include the listing of 29 base utilizes real-time access to the most current and accept- native hawthorns (Crataegus), 21 native oaks (Quercus), 11 ed taxonomy based on scientific consensus. -

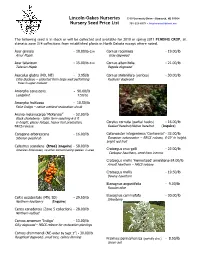

Nursery Price List

Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries 3310 University Drive • Bismarck, ND 58504 Nursery Seed Price List 701-223-8575 • [email protected] The following seed is in stock or will be collected and available for 2010 or spring 2011 PENDING CROP, all climatic zone 3/4 collections from established plants in North Dakota except where noted. Acer ginnala - 18.00/lb d.w Cornus racemosa - 19.00/lb Amur Maple Gray dogwood Acer tataricum - 15.00/lb d.w Cornus alternifolia - 21.00/lb Tatarian Maple Pagoda dogwood Aesculus glabra (ND, NE) - 3.95/lb Cornus stolonifera (sericea) - 30.00/lb Ohio Buckeye – collected from large well performing Redosier dogwood Trees in upper midwest Amorpha canescens - 90.00/lb Leadplant 7.50/oz Amorpha fruiticosa - 10.50/lb False Indigo – native wetland restoration shrub Aronia melanocarpa ‘McKenzie” - 52.00/lb Black chokeberry - taller form reaching 6-8 ft in height, glossy foliage, heavy fruit production, Corylus cornuta (partial husks) - 16.00/lb NRCS release Beaked hazelnut/Native hazelnut (Inquire) Caragana arborescens - 16.00/lb Cotoneaster integerrimus ‘Centennial’ - 32.00/lb Siberian peashrub European cotoneaster – NRCS release, 6-10’ in height, bright red fruit Celastrus scandens (true) (Inquire) - 58.00/lb American bittersweet, no other contaminating species in area Crataegus crus-galli - 22.00/lb Cockspur hawthorn, seed from inermis Crataegus mollis ‘Homestead’ arnoldiana-24.00/lb Arnold hawthorn – NRCS release Crataegus mollis - 19.50/lb Downy hawthorn Elaeagnus angustifolia - 9.00/lb Russian olive Elaeagnus commutata -

Lyonia Preserve Plant Checklist

Lyonia Preserve Plant Checklist Volusia County, Florida Aceraceae (Maple) Asteraceae (Aster) Red Maple Acer rubrum Bitterweed Helenium amarum Blackroot Pterocaulon virgatum Agavaceae (Yucca) Blazing Star Liatris sp. Adam's Needle Yucca filamentosa Blazing Star Liatris tenuifolia Nolina Nolina brittoniana Camphorweed Heterotheca subaxillaris Spanish Bayonet Yucca aloifolia Cudweed Gnaphalium falcatum Dog Fennel Eupatorium capillifolium Amaranthaceae (Amaranth) Dwarf Horseweed Conyza candensis Cottonweed Froelichia floridana False Dandelion Pyrrhopappus carolinianus Fireweed Erechtites hieracifolia Anacardiaceae (Cashew) Garberia Garberia heterophylla Winged Sumac Rhus copallina Goldenaster Pityopsis graminifolia Goldenrod Solidago chapmanii Annonaceae (Custard Apple) Goldenrod Solidago fistulosa Flag Paw paw Asimina obovata Goldenrod Solidago spp. Mohr's Throughwort Eupatorium mohrii Apiaceae (Celery) Ragweed Ambrosia artemisiifolia Dollarweed Hydrocotyle sp. Saltbush Baccharis halimifolia Spanish Needles Bidens alba Apocynaceae (Dogbane) Wild Lettuce Lactuca graminifolia Periwinkle Catharathus roseus Brassicaceae (Mustard) Aquifoliaceae (Holly) Poorman's Pepper Lepidium virginicum Gallberry Ilex glabra Sand Holly Ilex ambigua Bromeliaceae (Airplant) Scrub Holly Ilex opaca var. arenicola Ball Moss Tillandsia recurvata Spanish Moss Tillandsia usneoides Arecaceae (Palm) Saw Palmetto Serenoa repens Cactaceae (Cactus) Scrub Palmetto Sabal etonia Prickly Pear Opuntia humifusa Asclepiadaceae (Milkweed) Caesalpinceae Butterfly Weed Asclepias -

Genetic Relationships Among Cultivated Diploid Plums and Their Progenitors As Determined by RAPD Markers

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267951687 Genetic Relationships among Cultivated Diploid Plums and Their Progenitors as Determined by RAPD Markers Article in Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. American Society for Horticultural Science · July 2001 DOI: 10.21273/JASHS.126.4.451 CITATIONS READS 20 135 6 authors, including: Unaroj Boonprakob David H. Byrne Kasetsart University Texas A&M University 20 PUBLICATIONS 2,124 CITATIONS 272 PUBLICATIONS 5,750 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Rose breeding&genetics View project Rose Breeding and Genetics View project All content following this page was uploaded by David H. Byrne on 21 February 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. J. AMER. SOC. HORT. SCI. 126(4):451–461. 2001. Genetic Relationships among Cultivated Diploid Plums and Their Progenitors as Determined by RAPD Markers Unaroj Boonprakob1 and David H. Byrne2 Department of Horticultural Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-2133 Charles J. Graham Louisiana Agricultural Experiment Station, P.O. Box 539, Calhoun, LA 71225 W.R. Okie and Thomas Beckman U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Southeast Fruit and Tree Nut Research Laboratory, 111 Dunbar Rd., Byron, GA 31008 Brian R. Smith Department of Plant and Earth Science, University of Wisconsin-River Falls, River Falls, WI 54022 ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. germplasm, diversity, Prunus salicina, molecular markers, breeding, bootstrap analysis ABSTRACT. Diploid plums (Prunus L. sp.) and their progenitor species were characterized for randomly amplified polymorphic DNA polymorphisms. -

Prunus Umbellata: Flatwoods Plum1 Edward F

ENH-679 Prunus umbellata: Flatwoods Plum1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 Introduction General Information A native of the woods of the southeastern United States, Scientific name: Prunus umbellata Flatwoods Plum is a round-topped, deciduous tree, reach- Pronunciation: PROO-nus um-bell-AY-tuh ing 20 feet in height with a 15-foot spread, that is most Common name(s): Flatwoods Plum often planted for its spectacular display of blooms. It may Family: Rosaceae look a little ragged in winter. In late February, before the USDA hardiness zones: 8A through 9B (Fig. 2) two-inch-long, finely serrate leaves appear, these small trees Origin: native to North America take on a white, billowy, almost cloud-like appearance when Invasive potential: little invasive potential they are clothed in the profuse, small, white flower clusters. Uses: deck or patio; specimen; street without sidewalk; These half-inch blooms are followed by one-inch-long, parking lot island < 100 sq ft; parking lot island 100-200 sq edible, purple fruits which vary in flavor from very tart to ft; parking lot island > 200 sq ft; tree lawn 3-4 feet wide; tree sweet. These plums are very attractive to various forms of lawn 4-6 feet wide; tree lawn > 6 ft wide; highway median; wildlife. Bonsai; container or planter Availability: somewhat available, may have to go out of the region to find the tree Figure 1. Mature Prunus umbellata: Flatwoods Plum Figure 2. Range 1. This document is ENH-679, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture, UF/IFAS Extension. Original publication date November 1993.