A Geospatial Approach for Estimating Suitable Habitat and Population Size of the Invasive Northern Snakehead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Page # GENERAL INFORMATION Charles County Symbols......................................................................................................................47 Attractions.................................................................................................................................................48 Parks.............................................................................................................................................................51 Charles County Symbols Seal The Charles County seal is designed from the escutcheon of the first Lord Baltimore’s seal. The county was established in 1658. Flower The wild carrot, also called Queen Anne’s Lace, is commonly found along roads and through fields. Queen Anne’s Lace is a biennial with 1 to 3 foot stems and lacy flowers that do not blossom until their second year. Tree The Dogwood tree produces beautiful flowers each Spring. These flowers are usually small and have four or five petals. The berries that appear in the Fall are commonly eaten by birds in the winter. Bird The Great Blue Heron is the nation’s tallest bird. The bird is abundant along rivers and creeks and is a superb fisherman. Page 47 Attractions Our Past Preserved.... La Plata Train Station This historic building recalls the railroad’s impact on Charles County during the growth boom of the late 1800's. Port Tobacco Courthouse Settled in 1634, Port Tobacco was once Maryland’s second largest seaport and was listed on early World Maps. This settlement was originally the site of the Indian Village of Potopaco. Port Tobacco was the first county seat, but after the river began silting up and after a shift of occupations from tobacco farming to other trades and industry people moved to the town of La Plata where the new railroad was being built. The county seat was eventually moved to La Plata. The first Charles County Courthouse was completed in 1729, and a second one in 1819. -

II. Background

II. Background This chapter provides background information that was used as a basis for formulating the Preliminary Subregion 5 Master Plan and Proposed Sectional Map Amendment. Section A, Planning Context and Process, describes the location of the study area, the purposes of this master plan, prior plans and initiatives, and the public process used to prepare this master plan. Section B, Existing Conditions, contains profiles of Subregion 5 including the area’s history, demographic, economic, environmental, transportation and land use information. Section C, Key Issues, summarizes the key planning issues that are addressed in this master plan. A. Planning Context and Process Master Plan Study Area Boundaries The master plan study area includes land in south and southwest Prince George’s County generally bounded by the Potomac River, Tinkers Creek, Andrews Air Force Base, Piscataway Creek, the CSX (Popes Creek) railroad line, Mattawoman Creek, and the Charles County line. The subregion is approximately 74 square miles of land, equivalent to 15 percent of the total land area of Prince George’s County (See Map II-1, page 2). Within these boundaries are established and new residential neighborhoods, medical services, schools, commercial and industrial businesses, large retail centers, a regional park, two general aviation airports, a national park, environmental education centers, sand and gravel mining operations, a golf course, agriculture, and large forested areas. (See discussion of communities in section B. 6. and in Chapter IV, Land Use—Development Pattern.) For this master plan, Subregion 5 encompasses the following three communities (See Map II-2, page 3) in Planning Areas 81A, 81B, 83, 84, and 85A1. -

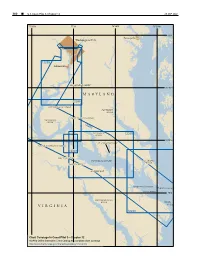

M a R Y L a N D V I R G I N

300 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 26 SEP 2021 77°20'W 77°W 76°40'W 76°20'W 39°N Annapolis Washington D.C. 12289 Alexandria PISCATAWAY CREEK 38°40'N MARYLAND 12288 MATTAWOMAN CREEK PATUXENT RIVER PORT TOBACCO RIVER NANJEMOY CREEK 12285 WICOMICO 12286 RIVER 38°20'N ST. CLEMENTS BAY UPPER MACHODOC CREEK 12287 MATTOX CREEK POTOMAC RIVER ST. MARYS RIVER POPES CREEK NOMINI BAY YEOCOMICO RIVER Point Lookout COAN RIVER 38°N RAPPAHANNOCK RIVER Smith VIRGINIA Point 12233 Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 3—Chapter 12 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 ¢ 301 Chesapeake Bay, Potomac River (1) This chapter describes the Potomac River and the above the mouth; thence the controlling depth through numerous tributaries that empty into it; included are the dredged cuts is about 18 feet to Hains Point. The Coan, St. Marys, Yeocomico, Wicomico and Anacostia channels are maintained at or near project depths. For Rivers. Also described are the ports of Washington, DC, detailed channel information and minimum depths as and Alexandria and several smaller ports and landings on reported by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), these waterways. use NOAA Electronic Navigational Charts. Surveys and (2) channel condition reports are available through a USACE COLREGS Demarcation Lines hydrographic survey website listed in Appendix A. (3) The lines established for Chesapeake Bay are (12) described in 33 CFR 80.510, chapter 2. Anchorages (13) Vessels bound up or down the river anchor anywhere (4) ENCs - US5VA22M, US5VA27M, US5MD41M, near the channel where the bottom is soft; vessels US5MD43M, US5MD44M, US4MD40M, US5MD40M sometimes anchor in Cornfield Harbor or St. -

2018 Countywide Watershed Assessment

Prince George’s County Countywide Watershed Assessment for MS4 Permit (2014-2019) December 21, 2018 Prepared For Prince George’s County, Maryland Department of the Environment Stormwater Management Division Prepared By Tetra Tech 10306 Eaton Place, Suite 340 Fairfax, VA 22030 Cover Photo Credits 1. Prince George’s County DoE 2. Prince George’s County DoE 3. Clean Water Partnership 4. M-NCPPC_Cassi Hayden Prince George’s County Countywide Watershed Assessment for MS4 Permit (2014–2019) Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms ................................................................................................. iv 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Prince George’s County Impaired Waters .................................................................................... 4 1.1.1 Impaired Water Bodies ....................................................................................................... 4 1.1.2 Causes of Water Body Impairment ..................................................................................... 6 1.2 Prince George’s County Restoration Plans .................................................................................. 8 2 Current Water Quality Conditions .................................................................................... 10 2.1 Biological Assessment ................................................................................................................ 10 2.1.1 Assessment -

Maryland Freshwater Regulations Fishing

dnr.maryland.gov MARYLAND GUIDE TO FISHING 2021 AND CRABBING STATE Photo by George Monk Photo by Karon Hickman RECORDS Photo by James McWhinney page 47 Also inside... • License Information • Seasons, Sizes Photo by Eric Packard Photo by Trey Lewis and Limits • Fish Identification • Public Lakes and Ponds • Tidal/Nontidal Dividing Lines Thomas Detrick, age 15 Photo by Eva Register Photo by Brett Poffenberger Elizabeth Lee Photo by R. Lee • Oysters and Clams ATLANTIC OCEAN | CHESAPEAKE BAY | COASTAL BAYS | NONTIDAL We Take Nervous OutWe of Take Breakdowns Nervous Out of Breakdowns $165* for Unlimited Towing...JOIN TODAY! $165* for Unlimited Towing...JOIN TODAY! With an Unlimited Towing Membership, breakdowns, running out GET THE APP IT’S THE of fuel and soft ungroundings don’t have to be so stressful. For a FASTEST WAY TO GET A TOW With anyear Unlimited of worry-free Towing boating, Membership, make TowBoatU.S. breakdowns, your backuprunning plan. out GET THE APP IT’S THE of fuel and soft ungroundings don’t have to be so stressful. For a FASTEST WAY TO GET A TOW year of worry-free boating,BoatUS.com/Towing make TowBoatU.S. or your 800-395-2628 backup plan. *One year Saltwater MembershipBoatUS.com/Towing pricing. Details of services provided can be found online at orBoatUS.com/Agree. 800-395-2628 TowBoatU.S. is not a rescue service. In an emergency situation, you must contact the Coast Guard or a government agency immediately. *One year Saltwater Membership pricing. Details of services provided can be found online at BoatUS.com/Agree. TowBoatU.S. -

STATE of MARYLAND BOARD of NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT of GEOLOGY, MINES and WATER RESOURCES Joseph T

STATE OF MARYLAND BOARD OF NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY, MINES AND WATER RESOURCES Joseph T. Singewald, Jr., Director BULLETIN 6 SHORE EROSION IN TIDEWATER MARYLAND CaliforniaState Division of Mines RECEIVED JAN 2 41950 library San Francisco, California BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 1949 Composed and Printed at Waverly Press, Inc. Baltimore, Md., U.S.A. COMMISSION ON GEOLOGY, MINES AND WATER RESOURCES Arthue B. Stewart, Chairman Baltimore Holmes D. Baker Frederick Harry R. Hall Hyattsville Joseph C. Lore, Jr Solomons Island Mervin A. Pentz Denton CONTENTS The Shore Erosion Problem. By Joseph T. Singewald, Jr 1 The Maryland Situation 1 Federal Legislation 2 Policy in Other Slates 2 Uniqueness of the Maryland Problem 3 Shore Erosion Damage in Maryland 4 Methods of Shore Front Protection 4 Examples of Shore Erosion Problems 6 Miami Beach 6 New Bay Shore Park 8 Mountain Point, Gibson Island 10 Tall Timbers, Potomac River 12 Tydings on the Bay and Log Inn, Anne Arundel County 14 Sandy Point State Park 15 What Should be done about Shore Erosion 16 The Shore Erosion Measurements. By Turhit H. Slaughter 19 Definition of Terms 19 Anne Arundel County 21 Baltimore County 28 Calvert County 31 Caroline County 35 Cecil County 37 Charles County 40 Dorchester County. 45 Harford County 54 Kent County 61 Prince Georges County 66 Queen Annes County 69 St. Marys County 75 Somerset County 84 Talbot County 91 Wicomico County 107 Worcester County 109 Summary of Shore Erosion in Tidewater Maryland 115 Navigation Restoration Expenditures. By Turbit If. Slaughter 119 References 121 Description of Plates 29 to 35 123 LIST OF TABLES 1. -

The Distribution of Submersed Aquatic Vegetation in the Fresh and Oligohaline Tidal Potomac River, 2005

The Distribution of Submersed Aquatic Vegetation in the Fresh and Oligohaline Tidal Potomac River, 2005 By Nancy B. Rybicki, Erika M. Justiniano- Vélez, Edward R. Schenk, Julie M. Baldizar and Sarah E. Hunter Potomac River Open-File Report 2008–1218 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Dirk Kempthorne, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 2008 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation: Rybicki, N.B., Justiniano- Vélez, E., Schenk, E.R., and Hunter, S.E., 2008, The Distribution of Submersed Aquatic Vegetation in the Fresh and Oligohaline Tidal Potomac River, 2005. US Geological Survey, Reston VA, Open-File Report 2008-1218, 40 pgs. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. Cover: Summer 2005 aerial photo of Dogue Creek and the Potomac River showing extensive dark areas of submersed aquatic vegetation. Photograph from Virginia Institute of Marine Science, http://www.vims.edu/bio/sav/2005_SAV_Photo_Gallery/pages/126-13_sept13-05.htm ii Contents Introduction............................................................................................................. -

2020 Charles County Nuisance Urban Flooding Plan

CHARLES COUNTY NUISANCE & URBAN FLOOD PLAN 10.2020 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Charles County Nuisance and Urban Flooding Problem Statement 1 Nuisance Flooding Plan and Considerations 1 Plan Purpose and Goals 3 Nuisance and Urban Flood Plan and 2018 Charles County Hazard Mitigation Plan 4 Nuisance and Urban Flooding Stakeholder Group 4 Nuisance and Urban Flooding Public Outreach Efforts 5 Nuisance and Urban Flooding ArcGIS StoryMap 6 Nuisance and Urban Flooding ArcGIS Podcast 7 Additional County Climate Action & Resiliency Efforts 7 Identification of Nuisance and Urban Flood Areas 10 Nuisance Flood Areas 25 Identification of Flood Thresholds, Water Levels, & Conditions 27 Flood Insurance Study (FIS) 27 Tidal Gauge Data 27 Tidal Gauge Data vs Flood Insurance Study Discussion 28 Sea Level Rise and Shoreline Erosion 28 Stormwater & Drainage Ordinances & Improvements Projects 32 Stormwater Management Ordinance 32 Storm Drainage Ordinance 32 Stormwater Management and Impervious Surface 33 Drainage Improvement Projects 33 Nuisance & Urban Flood Response, Preparedness, & Mitigation 35 Drainage Improvement Plan & Project Prioritization Criteria 56 Implementation & Monitoring 57 Continuous Communication with the Public 57 Appendix Appendix 1. NCEI Storm Event Data- Charles County Roadway Flooding Events 58 Tables Table 1. Nuisance and Urban Flood Locations 13 Table 2. Nuisance and Urban Flooding Preparedness, Response, & Mitigation 37 Maps Map 1. Charles County Nuisance and Urban Flood Locations 12 Map 2. Charles County Nuisance Flood Locations 26 Acknowledgements This planning project has been made possible by grant funding from the EPA, provided by Maryland Department of Natural Resources through the Grants Gateway. County Commissioners: Rueben B. Collins, II Bobby Rucci Gilbert O. -

MARYLAND BIOLOGICAL STREAM SURVEY 2000-2004 Volume I

MARYLAND BIOLOGICAL STREAM SURVEY 2000-2004 VOLUME I ECOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF WATERSHEDS SAMPLED IN 2000 CHESAPEAKEBAY AND WATERSHED PROGRAMS MONITORINGAND NON-TIDAL ASSESSMENT CBWP-MANTA-EA-01-5 Parris N. Glendening Kathleen Kennedy Townsend Governor Lt. Governor A message to Maryland’s citizens The Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) seeks to preserve, protect and enhance the living resources of the state. Working in partnership with the citizens of Maryland, this worthwhile goal will become a reality. This publication provides information that will increase your understanding of how DNR strives to reach that goal through its many diverse programs. J. Charles Fox Karen M. White Secretary Deputy Secretary Maryland Department of Natural Resources Tawes State Office Building 580 Taylor Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21401 Toll free in Maryland: 1-(877) 620 8DNR x8611 Out of state call: 410-260-8611 www.dnr.state.md.us The facilities and services of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin, physical or mental disability. This document is available in alternative format upon request from a qualified individual with a disability. Publication date: September 2001 PRINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER MARYLAND BIOLOGICAL STREAM SURVEY 2000-2004 Volume I: Ecological Assessment of Watersheds Sampled in 2000 Prepared for Maryland Department of Natural Resources Tawes State Office Building 580 Taylor Avenue Annapolis, MD 21401 Prepared by Nancy E. Roth Mark T. Southerland Ginny Mercurio JonH.Vølstad Versar, Inc. 9200 Rumsey Road Columbia, MD 21045 August 2001 FOREWORD This report, Maryland Biological Stream Survey 2000-2004, Volume I: Ecological Assessment of Watersheds Sampled in 2000, supports the Maryland Department of Natural Resources' Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) under the direction of Dr. -

CH-526 Morris T. Wampler Hunting Lodge, (Wampler Cottage)

CH-526 Morris T. Wampler Hunting Lodge, (Wampler Cottage) Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 11-21-2003 CH-526 1927 Wampler Hunting Lodge Fenwick vie. Private The Wampler Hunting Lodge, built in 1927, consists of a small Craftsman-inspired cottage with a massive exterior stone chimney at its gable end. The building has been significantly altered since its construction, but retains its original cladding and basic form. The Wampler Lodge is a remnant of a bustling early 20th century community that started here around 1909 as a summer cottage resort. The building, which retains its original form and some of its original materials, is one of only a handful of early structures in the town that remain relatively intact. -

Gazetteer of Maryland

Bulletin No. 231 Series F, Geography, 39 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOK GAZETTEER OF MARYLAND BY HENRY. QA.NISTETT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1904 0 tf y LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, Washington, D. C., March 9, 1904. SIR: I have the honor to transmit herewith, for publication as a bulletin, a gazetteer of Maryland. Very respectfully, HENRY GANNETT,. Geographer. Hon. CHARLES D. WALCOTT, Director United States Geological Survey. 3 A GAZETTEER OF MARYLAND. By HENRY GANNETT. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE STATE. Maryland is one of the Eastern States, bordering on the Atlantic Ocean, about midway between the northern and southern boundaries of the country. It lies between latitudes 37° 53' and 39° 44', and between longitudes 75° 04 and 79° 33'. Its neighbors are Pennsyl vania on the north, West Virginia and Virginia on the west and south, and Delaware on the east. Its north boundary is Mason and Dixon's line, and its east boundary is, in part, a nearly north-south line separating it from Delaware and Pennsylvania, and, in part, the Atlantic Ocean. On the south the boundary is an irregular line across the peninsula separating Chesapeake Bay from the Atlantic Ocean; then across Chesapeake Bay to the southern point of the entrance to Potomac River; thence following the low-water line on the south bank of the Potoniac to the head of the north branch of that river, at a point known as Fairfax Stone, excepting the area of the District of Columbia. -

Law Enforcement Officers of the State of Maryland Authorized to Issue Citat

JOHN P. MORRISSEY DISTRICT COURT OF MARYLAND 580 Taylor Avenue Chief Judge Suite A-3 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 Tel: (410) 260-1525 Fax: (410) 974-5026 December 29, 2017 TO: All Law Enforcement Officers of the State of Maryland Authorized to Issue Citations for Violations of the Natural Resources Laws The attached list is a fine or penalty deposit schedule for certain violations of the Natural Resources laws. The amounts set out on this schedule are to be inserted by you in the appropriate space on the citation. The defendant in such cases, who does not care to contest guilt, may prepay the fine in that amount. The fine schedule is applicable whether the charge is made by citation, a statement of charges, or by way of criminal information. For some violations, a defendant must stand trial and is not permitted to prepay a fine or penalty deposit. Additionally, there may be some offenses for which there is no fine listed. In both cases you should check the box which indicates that the defendant must appear in court on the offense. I understand that this fine schedule has been approved for legal sufficiency by the Office of the Attorney General, Department of Natural Resources. This schedule has, therefore, been adopted pursuant to the authority vested in the Chief Judge of the District Court by the Constitution and laws of the State of Maryland. It is effective January 1, 2018, replacing all schedules issued prior hereto, and is to remain in force and effect until amended or repealed. No law enforcement officer in the State is authorized to deviate from this schedule in any case in which he or she is involved.