Gwyneth Lewis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wales: the Heart of the Debate?

www.iwa.org.uk | Winter 2014/15 | No. 53 | £4.95 Wales: The heart of the debate? In the rush to appease Scottish and English public opinion will Wales’ voice be heard? + Gwyneth Lewis | Dai Smith | Helen Molyneux | Mark Drakeford | Rachel Trezise | Calvin Jones | Roger Scully | Gillian Clarke | Dylan Moore | The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges funding support from the the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation. The following organisations are corporate members: Public Sector Private Sector Voluntary Sector • Aberystwyth University • Acuity Legal • Age Cymru • BBC Cymru Wales • Arriva Trains Wales • Alcohol Concern Cymru • Cardiff County Council • Association of Chartered • Cartrefi Cymru • Cardiff School of Management Certified Accountants (ACCA) • Cartrefi Cymunedol • Cardiff University Library • Beaufort Research Ltd Community Housing Cymru • Centre for Regeneration • Blake Morgan • Citizens Advice Cymru Excellence Wales (CREW) • BT • Community - the union for life • Estyn • Cadarn Consulting Ltd • Cynon Taf Community Housing Group • Glandwr Cymru - The Canal & • Constructing Excellence in Wales • Disability Wales River Trust in Wales • Deryn • Eisteddfod Genedlaethol Cymru • Harvard College Library • Elan Valley Trust • Federation of Small Businesses Wales • Heritage Lottery Fund • Eversheds LLP • Friends of the Earth Cymru • Higher Education Wales • FBA • Gofal • Law Commission for England and Wales • Grayling • Institute Of Chartered Accountants • Literature Wales • Historix (R) Editions In England -

Bread Loaf School of English 2018 Course Catalog

BREAD LOAF SCHOOL OF ENGLISH 2018 COURSE CATALOG SUMMER 2018 1 SUMMER 2018 SESSION DATES VERMONT Arrival and registration . June 26 Classes begin . June. 27 Classes end . August. 7 Commencement . August. 11 NEW MEXICO Arrival and registration . June 16–17 Classes begin . June. 18 Classes end . July . 26 Commencement . July. 26 OXFORD Arrival . June 25 Registration . June . 26 Classes begin . June. 27 Classes end . August. 3 Commencement . August. 4 2 BLSE WELCOME TO BREAD LOAF WHERE YOU’LL FIND ■ A unique chance to recharge ■ A dynamic peer community of your imagination teachers, scholars, and working professionals ■ Six uninterrupted weeks of rigorous graduate study ■ A full range of cocurricular opportunities ■ Close interaction with a distinguished faculty ■ A game-changing teachers’ network ■ An expansive curriculum in literature, pedagogy, and creative arts SUMMER 2018 1 IMMERSIVE GEOGRAPHICALLY DISTINCTIVE The ideal place for teachers and working Three campuses providing distinctive cultural professionals to engage with faculty and peers and educational experiences. Read, write, and in high-intensity graduate study, full time. Field create in the enriching contexts of Vermont’s trips, readings, performances, workshops, and Green Mountains, Santa Fe, and the city and other events will enrich your critical and creative university of Oxford. thinking. FLEXIBLE EXPANSIVE Education suited to your goals and building on The only master’s program that puts courses your talents, interests, and levels of expertise. in English, American, and world literatures in Come for one session, or pursue a master’s degree conversation with courses in creative writing, across four to five summers. pedagogy, and theater arts. Think across disciplinary boundaries, and learn from faculty INDIVIDUALIZED who bring diverse approaches to what and how Instruction and advising individualized to they teach. -

Welsh Horizons Across 50 Years Edited by John Osmond and Peter Finch Photography: John Briggs

25 25 Vision Welsh horizons across 50 years Edited by John Osmond and Peter Finch Photography: John Briggs 25 25 Vision Welsh horizons across 50 years Edited by John Osmond and Peter Finch Photography: John Briggs The Institute of Welsh Affairs exists to promote quality research and informed debate affecting the cultural, social, political and economic well being of Wales. The IWA is an independent organisation owing no allegiance to any political or economic interest group. Our only interest is in seeing Wales flourish as a country in which to work and live. We are funded by a range of organisations and individuals, including the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, and the Waterloo Foundation. For more information about the Institute, its publications, and how to join, either as an individual or corporate supporter, contact: IWA - Institute of Welsh Affairs, 4 Cathedral Road, Cardiff CF11 9LJ T: 029 2066 0820 F: 029 2023 3741 E: [email protected] www.iwa.org.uk www.clickonwales.org Inspired by the bardd teulu (household poet) tradition of medieval and Renaissance Wales, the H’mm Foundation is seeking to bridge the gap between poets and people by bringing modern poetry more into the public domain and particularly to the workplace. The H’mm Foundation is named after H’m, a volume of poetry by R.S. Thomas, and because the musing sound ‘H’mm’ is an internationally familiar ‘expression’, crossing all linguistic frontiers. This literary venture has already secured the support of well-known poets and writers, including Gillian Clarke, National Poet for Wales, Jon Gower, Menna Elfyn, Nigel Jenkins, Peter Finch and Gwyneth Lewis. -

Gwyneth Lewis Papers (GB 0210 GWYNETHLEW)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Gwyneth Lewis Papers (GB 0210 GWYNETHLEW) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Argraffwyd: Hydref 11, 2019 Printed: October 11, 2019 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; RDA NACO; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/gwyneth-lewis-papers-newydd https://archives.library.wales/index.php/gwyneth-lewis-papers-newydd Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llyfrgell.cymru Gwyneth Lewis Papers Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 4 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 5 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

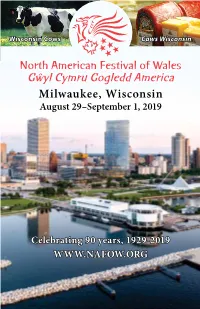

NAFOW Program Booklet

Wisconsin Cows Caws Wisconsin North American Festival of Wales Gŵyl Cymru Gogledd America Milwaukee, Wisconsin August 29–September 1, 2019 Celebrating 90 years, 1929-2019 WWW.NAFOW.ORG ’ For over 130 years, working to celebrate, preserve, The Calgary Welsh Society and promote Welsh cultural heritage in the Cymdeithas Gymreig Calgary Southwestern Pennsylvania region. PROUD TO SUPPORT NAFOW 2019 in MILWAUKEE Founded by John Morris – ‘Morris Bach’ in 1906 Proud supporters of the Welsh North American Association Website: calgarywelshsociety.com Facebook page: Calgary Welsh Society Welsh Language Classes DEWCH I YMWELD Â NI Cultural Festivals COME & VISIT US at the Wales-Pennsylvania Digitization Project GREAT PLAINS WELSH HERITAGE CENTRE Museum • Library • One-Room School Annual Daffodil Luncheon Archive For Welsh America Gymanfa Ganu Visitors & researchers welcome! St. David’s and Owain Glyndŵr Pub Crawls Learn more at our table in the marketplace. 307 S. Seventh Street Carnegie Library Welsh Collection P.O. Box 253 Wymore, NE 68466 University of Pittsburgh Welsh Nationality Room welshheritageproject.org Visit: stdavidssociety.org (402) 645-3186 [email protected] Facebook: welshsociety.pittsburgh Photo: Welsh Nationality Room in Cathedral of Learning at University of Pittsburgh 1 Croeso! Welcome to the North American Festival of Wales Milwaukee 2019 Cynnwys/Table of Contents Hotel Floor Plan ........................................................................................... 4–5 Schedule at a Glance .................................................................................... -

Download (4MB)

‘Pursuing God’ Poetic Pilgrimage and the Welsh Christian Aesthetic A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the regulations of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature at Cardiff University, School of English, Communication and Philosophy, by Nathan Llywelyn Munday August 2018 Supervised by Professor Katie Gramich (Cardiff University) Dr Neal Alexander (Aberystwyth University) 2 CONTENTS List of Illustrations 5 List of Tables 6 Abstract 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introduction - ‘Charting the Theologically-charged Space of Wales’ 9 ‘For Pilgrymes are we alle’ – The Ancient Metaphor 10 ‘Church Going’ and the ‘Unignorable Silence’ 13 The ‘Secularization Theory’ or ‘New Forms of the Sacred’? 20 The Spiritual Turn 29 Survey of the Field – Welsh Poetry and Religion 32 Wider Literary Criticism 45 Methodology 50 Chapter 1 - ‘Ann heard him speak’: Ann Griffiths (1776- 1805) and Calvinistic Mysticism 61 Calvinistic Methodism 63 Methodist Language 76 Rhyfedd | Strange / Wondrous 86 Syllu ar y Gwrthrych | To Gaze on the Object 99 Pren |The Tree 109 Fountains and Furnaces 115 Modern Responses 121 Mererid Hopwood (b. 1964) 124 Sally Roberts Jones (b.1935) 129 Rowan Williams (b.1950) 132 R. S. Thomas (1913-2000) 137 Conclusion 146 Chapter 2 - ‘Gravitating […] to this ground’ – Traversing the Nonconformist Nation[s] (c. 1800-1914) 147 3 The Hymn – an evolving form in a changing context 151 The Form 151 The Changing Context 153 The Formation of the Denominations and their effect on the hymn 159 Hymn Singing 162 The Nonconformist Nation[s] 164 ‘Beulah’ -

Ruth Macdonald Finalised Thesis

RETHINKING THE HOMERIC HERO IN CONTEMPORARY BRITISH WOMEN’S WRITING: CLASSICAL RECEPTION, FEMINIST THEORY AND CREATIVE PRACTICE Ruth MacDonald Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Royal Holloway, University of London. Declaration of Authorship I Ruth MacDonald hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed:_____________________________________ Date:_______________________________________ - 2 - Abstract Sustained engagements with ciphers of traditional Homeric stereotypes can be found in a number of texts written by women. This thesis will examine how three texts in particular, Elizabeth Cook’s Achilles (2001), Gwyneth Lewis’s A Hospital Odyssey (2010) and Kate Tempest’s Brand New Ancients (2012), allow an argument to develop for the centrality of various strategies and perspectives, such as embodiment and intersubjectivity. I suggest that the figuration of the nomad, as articulated in the philosophies of Gilles Deleuze and Rosi Braidotti in particular, is key to understanding both twenty-first century experiences and expressions of corporeality, as well as receptions of the Homeric hero in women’s writing today. Heroic bodies in Cook, Lewis, and Tempest are vulnerable and liminal, oscillating between borderlines or lurking at the margins, disrupting heteronormative systems and structures by transgressing boundaries, codes and limits in the relationship between value, the body and the mind as traditionally understood. Though in some obvious ways distant, the Homeric heroic body nevertheless retains a resonance and influence in twenty-first century British cultural understandings. This thesis thus explores the role of an ‘intimate other’ (the Homeric hero) in engaging classical reception, feminist politics and contemporary women’s writing in dialogue. -

Our Creative Capital 2 Cardiff - Our Creative Capital

CARDIFF OUR CREATIVE CAPITAL 2 CARDIFF - OUR CREATIVE CAPITAL CARDIFF CREATIVE MINDS Wales is a hotbed of both creativity and industry - a unique melting pot of literature, music and drama - and sheer hard graft. If there’s one thing I have learned over the years, it is that Wales is not afraid of hard work or a challenge. Jane Tranter, CEO Bad Wolf CARDIFF - OUR CREATIVE CAPITAL 3 WHO IS HERE 4PI PRODUCTIONS | ALERT LOGIC | AMPLYFI | ARUP | ATTICUS DIGITAL | AUSTIN SMITH | AVANTI MEDIA | BACKBASE | BAD WOLF | BAFTA CYMRU | BAIT STUDIO | BANG POST PRODUCTION | BAREFOOT RASCALS | BBC CYMRU WALES | BENGO MEDIA | BOOM CYMRU | BOOMERANG | BOX UK | BLUE STAG | CARDIFF THEATRICAL SERVICES | CELF CREATIVE | CHAPTER | CLOTH CAT ANIMATION | CLWB IFOR BACH | COPA | CURVE MEDIA | DEADSTAR PUBLISHING | DEERHEART | DELIO | DEVOPSGROUP | DRAGONFLY | DREEM | FFILM CYMRU WALES | FFOTOGALLERY | FICTION FACTORY | FIREWORKS | FOLK FILMS | GEOLANG | GOLLEY SLATER | GORILLA | HASSELL | HEADLINE ACCENT | HOLDER MATHIAS | IEIE PRODUCTIONS | ILLUSTRATE DIGITAL | INSPIRETEC | ITV CYMRU WALES | JAMMY CUSTARD ANIMATION | KAGOOL | LIBERTY MARKETING | LIMEGREEN TANGERINE | MAKERS GUILD OF WALES | MARTHA STONE | MILK VFX | MUSICBOX STUDIOS | MYNT MEDIA | NIMBLE DRAGON | ONE TRIBE TV | ORCHARD MEDIA | PARASOL MEDIA | PLIMSOLL PRODUCTIONS | POWELL DOBSON | RANT MEDIA | RIO ARCHITECTS | RONDO MEDIA | S3 ADVERTISING | S4C | SANDERS DESIGN | SCOTT BROWNRIGG | SCREEN ALLIANCE WALES | SLAM MEDIA | SOUNDWORKS | STILLS | STRIDE TREGLOWN | SUGAR CREATIVE | SUGAR FILMS | THREAD DESIGN & DEVELOPMENT | THUD MEDIA | TIDY PRODUCTIONS | TINY REBEL GAMES | TRAFFIC JAM MEDIA | UPRISE VSI | VOX PICTURES | WEALTHIFY | WE BUILD BOTS | WILDFLAME PRODUCTIONS | YOKE CREATIVE 4 CARDIFF - OUR CREATIVE CAPITAL DID YOU KNOW? A few years before Walt Disney debuted Mickey Mouse, Cardiff had its own animated mascot: an adventurous and untamed dog named Jerry the Troublesome Tyke, created in 1925 by Sid Griffi ths. -

UIJT!XFFL! Thursday at 7Pm

Uif!Obnjoh!pg!Kftvt Weekly Newsletter No.218 1 Sunday, 1st January, 2017 11.00 am Sung Eucharist & Sermon. Hymns: Joy to the World, 68, Abba Father, Anthem: The Lord bless you and keep you (Rutter), 594. Settings: Thomas Mass (David Thorne). 7.00 pm Choral Evensong. Introit: All this time (Walton). Psalm 115. Hymns: 539, Anthem: New Year Carol (Britten), 271. Magnificat & Nunc Dimittis: Norman Doe. Readings: Deuteronomy 30, 1-20. Acts 3, 1-16. In the world-wide Church we pray today for the Diocese of Kolhapur in the Church of North India (United), and Bishop Bathuel Tiwade and in the Ecumenical Prayer Cycle we pray for Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Palestine. We pray for peace in the world, remembering the people of Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Ukraine, Israel and Gaza, and we pray for all migrants and refugees fleeing places of war and persecution. We pray for the United Nations, especially those involved in the key role of conciliation, for retiring Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon, and for António Guterres who succeeds to the post today. We pray for the victims of the floods in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where many have died and thousands have been left homeless. In this diocese we pray for the Parish of Cwmafan, Rev Elaine Jenkyns, Rev Stephen Jenkyns and Reader Susan Powell. We pray for the sick and those who care for them, especially Glyn Osman, Julie Romanelli, Bill Berry, John Matthias, Nigel Rees, Charles Murray, Alec Colley and Mary Traynor. We pray for the repose of the souls of the departed, especially Margaret Shepherd, whose anniversary occurs at this time.