Oligosoma Otagense)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary of Native Bat, Reptile, Amphibian and Terrestrial Invertebrate Translocations in New Zealand

Summary of native bat, reptile, amphibian and terrestrial invertebrate translocations in New Zealand SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 303 Summary of native bat, reptile, amphibian and terrestrial invertebrate translocations in New Zealand G.H. Sherley, I.A.N. Stringer and G.R. Parrish SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 303 Published by Publishing Team Department of Conservation PO Box 10420, The Terrace Wellington 6143, New Zealand Cover: Male Mercury Islands tusked weta, Motuweta isolata. Originally found on Atiu or Middle Island in the Mercury Islands, these were translocated onto six other nearby islands after being bred in captivity. Photo: Ian Stringer. Science for Conservation is a scientific monograph series presenting research funded by New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC). Manuscripts are internally and externally peer-reviewed; resulting publications are considered part of the formal international scientific literature. Individual copies are printed, and are also available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Science & technical. © Copyright April 2010, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1173–2946 (hardcopy) ISSN 1177–9241 (PDF) ISBN 978–0–478–14771–1 (hardcopy) ISBN 978–0–478–14772–8 (PDF) This report was prepared for publication by the Publishing Team; editing by Amanda Todd and layout by Hannah Soult. Publication was approved by the General Manager, Research and Development Group, Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. CONTENTS Abstract 5 1. Introduction 6 2. Methods 7 3. -

Oligosoma Ornatum; Reptilia: Scincidae) Species Complex from Northern New Zealand

Zootaxa 3736 (1): 054–068 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3736.1.2 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:B7D72CD9-BE5D-4603-8BC0-C9FA557C7BEE Taxonomic revision of the ornate skink (Oligosoma ornatum; Reptilia: Scincidae) species complex from northern New Zealand GEOFF B. PATTERSON1,5, ROD A. HITCHMOUGH2 & DAVID G. CHAPPLE3,4 1149 Mairangi Road, Wilton, Wellington, New Zealand 2Department of Conservation, Terrestrial Conservation Unit, PO Box 10-420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand 3School of Biological Sciences, Monash University, Clayton Victoria 3800, Australia 4Allan Wilson Centre for Molecular Ecology and Evolution, School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, P.O. Box 600, Wellington 6140, New Zealand 5Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Although the New Zealand skink fauna is known to be highly diverse, a substantial proportion of the recognised species remain undescribed. We completed a taxonomic revision of the ornate skink (Oligosoma ornatum (Gray, 1843)) as a pre- vious molecular study indicated that it represented a species complex. As part of this work we have resolved some nomen- clatural issues involving this species and a similar species, O. aeneum (Girard, 1857). A new skink species, Oligosoma roimata sp. nov., is described from the Poor Knights Islands, off the northeast coast of the North Island of New Zealand. This species is diagnosed by a range of morphological characters and genetic differentiation from O. ornatum. The con- servation status of the new taxon appears to be of concern as it is endemic to the Poor Knights Islands and has rarely been seen over the past two decades. -

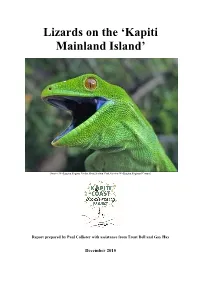

Lizards on the 'Kapiti Mainland Island'

Lizards on the ‘Kapiti Mainland Island’ Source: Wellington Region: Gecko Identification Card, Greater Wellington Regional Council Report prepared by Paul Callister with assistance from Trent Bell and Gay Hay December 2015 Our ‘Kapiti Mainland Island’ area The area covered by the ‘Mainland Island’ comprises Queen Elizabeth Park, Whareroa Farm Reserve and the Paekakariki-Pukerua Bay escarpment.1 Vision In the next decade lizards will become abundant within this Kapiti Mainland Island. Goals to gain an understanding of lizard diversity and abundance in Queen Elizabeth Park, Whareroa Farm Reserve and on the Paekakariki-Pukerua Bay escarpment through lizard surveys and monitoring programmes.. to improve animal pest control regimes so they protect existing lizard populations and allow these populations to stabilise or recover based on the surveys and expert advice from herpetologists.. to assist the recovery of lizard populations by improving their habitat. 1 The escarpment commences near Muri Station and finishes at Paekakariki. It excludes the escarpment above Pukerua Bay beach. Introduction Lizards are New Zealand’s largest terrestrial vertebrate group with more than 100 species (and counting!). They occupy almost all available ecosystems from coastal shores to mountain peaks. Lizards play an important role in ecosystem processes and function as predators, pollinators, frugivores and seed dispersers. Despite 85 percent of this fauna being threatened or at-risk, lizards are everywhere around us and can be exceptionally abundant when released from mammalian predation pressure. Lizards are emerging as iconic flagship and indicator species in conservation and ecological restoration. In 2012 the Wellington Regional Lizard Network published a lizard strategy for the Wellington region (Romijn et al. -

Biodiversity Conservation and Phylogenetic Systematics Preserving Our Evolutionary Heritage in an Extinction Crisis Topics in Biodiversity and Conservation

Topics in Biodiversity and Conservation Roseli Pellens Philippe Grandcolas Editors Biodiversity Conservation and Phylogenetic Systematics Preserving our evolutionary heritage in an extinction crisis Topics in Biodiversity and Conservation Volume 14 More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/7488 Roseli Pellens • Philippe Grandcolas Editors Biodiversity Conservation and Phylogenetic Systematics Preserving our evolutionary heritage in an extinction crisis With the support of Labex BCDIV and ANR BIONEOCAL Editors Roseli Pellens Philippe Grandcolas Institut de Systématique, Evolution, Institut de Systématique, Evolution, Biodiversité, ISYEB – UMR 7205 Biodiversité, ISYEB – UMR 7205 CNRS MNHN UPMC EPHE, CNRS MNHN UPMC EPHE, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle Sorbonne Universités Sorbonne Universités Paris , France Paris , France ISSN 1875-1288 ISSN 1875-1296 (electronic) Topics in Biodiversity and Conservation ISBN 978-3-319-22460-2 ISBN 978-3-319-22461-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-22461-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015960738 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 . The book is published with open access at SpringerLink.com. Chapter 15 was created within the capacity of an US governmental employment. US copyright protection does not apply. Open Access This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License, which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. All commercial rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Incorporated

THE AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY OF HERPETOLOGISTS INCORPORATED NEWSLETTER 49 Published 29 September 2014 2 Letter from the editor I trust you found yourselves securely amused in the ever capable hands of that respectably amiable Professor Keogh and saucy Dr Mitzy during the 2014 ASH conference. The 2014 AGM was the first meeting I have missed since I attended my first ASH at 21 years old in Healesville Victoria. A time of a young and impressionable heart left seduced by Rick Shines, well… shine I suppose, a top a bald and knowledgeable head, awed by the insurmountable yet witty detail of Glenn Shea's trivia (not to mention that beard) and left speechless by the ever inappropriate, wildly handsome and ridiculously witty Mr Clemann. I welcome the newbys to a society that holds a unique place in Australian science. Where the brains and ideas of some of Australia's top scientists are corrupted by their inner herpetological brawn, where copious quantities of beer often leave even the most innocent of professors busting out the most quality of limbo attempts, break dance moves... or just plain naked. Where Conrad Hoskin becomes a lake Ayer dragon to avoid courtship rituals, where the obscure snores of Matthew Greenlees leave phylogenetists confused with analogous evolutionary traits, and where Mark Hutchinson’s intimate relationship with every single lizard in the entire country including coastal fringes and off shore islands, puts everyone to shame and anyone left to sleep. It is with deep regret and sheer delight that I could not join you this year, for my inner black mumma has met with my chameleon calling to leave my big island home and travel west to Madagascar where I am set up, working part time for University of Newcastle and part time for a local organisation called Madagasikara Voakajy for an indeterminate period. -

New Zealand Threat Classification System (NZTCS)

NEW ZEALAND THREAT CLASSIFICATION SERIES 17 Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015 Rod Hitchmough, Ben Barr, Marieke Lettink, Jo Monks, James Reardon, Mandy Tocher, Dylan van Winkel and Jeremy Rolfe Each NZTCS report forms part of a 5-yearly cycle of assessments, with most groups assessed once per cycle. This report is the first of the 2015–2020 cycle. Cover: Cobble skink, Oligosoma aff.infrapunctatum “cobble”. Photo: Tony Jewell. New Zealand Threat Classification Series is a scientific monograph series presenting publications related to the New Zealand Threat Classification System (NZTCS). Most will be lists providing NZTCS status of members of a plant or animal group (e.g. algae, birds, spiders). There are currently 23 groups, each assessed once every 3 years. After each three-year cycle there will be a report analysing and summarising trends across all groups for that listing cycle. From time to time the manual that defines the categories, criteria and process for the NZTCS will be reviewed. Publications in this series are considered part of the formal international scientific literature. This report is available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Series. © Copyright December 2016, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 2324–1713 (web PDF) ISBN 978–1–98–851400–0 (web PDF) This report was prepared for publication by the Publishing Team; editing and layout by Lynette Clelland. Publication was approved by the Director, Terrestrial Ecosystems Unit, Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. Published by Publishing Team, Department of Conservation, PO Box 10420, The Terrace, Wellington 6143, New Zealand. -

Species Richness in Time and Space: a Phylogenetic and Geographic Perspective

Species Richness in Time and Space: a Phylogenetic and Geographic Perspective by Pascal Olivier Title A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ecology and Evolutionary Biology) in The University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Assistant Professor and Assistant Curator Daniel Rabosky, Chair Associate Professor Johannes Foufopoulos Professor L. Lacey Knowles Assistant Professor Stephen A. Smith Pascal O Title [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-6316-0736 c Pascal O Title 2018 DEDICATION To Judge Julius Title, for always encouraging me to be inquisitive. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research presented in this dissertation has been supported by a number of research grants from the University of Michigan and from academic societies. I thank the Society of Systematic Biologists, the Society for the Study of Evolution, and the Herpetologists League for supporting my work. I am also extremely grateful to the Rackham Graduate School, the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology C.F. Walker and Hinsdale scholarships, as well as to the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Block grants, for generously providing support throughout my PhD. Much of this research was also made possible by a Rackham Predoctoral Fellowship, and by a fellowship from the Michigan Institute for Computational Discovery and Engineering. First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Dan Rabosky, for taking me on as one of his first graduate students. I have learned a tremendous amount under his guidance, and conducting research with him has been both exhilarating and inspiring. I am also grateful for his friendship and company, both in Ann Arbor and especially in the field, which have produced experiences that I will never forget. -

Significant Indigenous Biodiversity

Schedule 6 – Significant indigenous biodiversity This schedule identifies indigenous species, ecosystems and habitats identified as being regionally significant for their coastal indigenous biodiversity values. Schedule 6A includes a table identifying coastal indigenous flora and fauna species identified as threatened or at risk of extinction and another table identifying naturally rare and uncommon ecosystem types found on the Taranaki coast. Schedule 6B identifies sensitive marine benthic habitats. Schedule 6A Threatened and At Risk Species Found Coastal NZTCS1 category IUCN2 Regionally Estuary Group Scientific Name Intertidal bioclimatic Marine and (conservation status) Classification Distinctive (CMA or (CMA) zone (above (CMA) Land) CMA) Antarctic prion Pachyptila desolata At Risk ((Naturally Uncommon)) Least concern Antipodean wandering albatross Diomedea antipodensis antipodensis Threatened (Nationally Critical) Vulnerable Black petrel Procellaria parkinsoni Threatened (Nationally Vulnerable) Vulnerable Broad-billed prion Pachyptila vittata At Risk (Relict) Least concern Buller's shearwater Puffinus bulleri At Risk (Naturally Uncommon) Vulnerable Caspian tern Hydroprogne caspia Threatened (Nationally Vulnerable) Least concern CMA, Land Fairy prion Pachyptila turtur At Risk (Relict) Least concern Bird Flesh-footed shearwater Puffinus carneipes Threatened (Nationally Vulnerable) Least concern Grey-faced petrel Pterodroma macroptera gouldi Not Threatened Grey-headed mollymawk Thalassarche chrysostoma Threatened (Nationally -

Legal Protection of New Zealand's Indigenous Terrestrial Fauna

Tuhinga 25: 25–101 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2014) Legal protection of New Zealand’s indigenous terrestrial fauna – an historical review Colin M. Miskelly Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: New Zealand has had a complex history of wildlife protection, with at least 609 different pieces of legislation affecting the protection of native wildlife between 1861 and 2013. The first species to be fully protected was the tüï (Prosthemadera novaeseelandiae), which was listed as a native game species in 1873 and excluded from hunting in all game season notices continuously from 1878, until being absolutely protected in 1906. The white heron (Ardea modesta) and crested grebe (Podiceps cristatus) were similarly protected nationwide from 1888, and the huia (Heteralocha acutirostris) from 1892. Other species listed as native game before 1903 were not consistently excluded from hunting in game season notices, meaning that such iconic species as kiwi (Apteryx spp.), käkäpö (Strigops habroptilus), kökako (Callaeas spp.), saddlebacks (Philesturnus spp.), stitchbird (Notiomystis cincta) and bellbird (Anthornis melanura) could still be taken or killed during the game season until they were absolutely protected in 1906. The tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) was added to the native game list in 1895, but due to inadequate legislation was not absolutely protected until 1907. The Governor of the Colony of New Zealand had the power to absolutely protect native birds from 1886, but this was not used until 1903, when first the blue duck (Hymenolaimus malacorhynchus) and then the huia were given the status of absolutely protected, followed by more than 130 bird species by the end of 1906. -

The High-Level Classification of Skinks (Reptilia, Squamata, Scincomorpha)

Zootaxa 3765 (4): 317–338 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3765.4.2 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:357DF033-D48E-4118-AAC9-859C3EA108A8 The high-level classification of skinks (Reptilia, Squamata, Scincomorpha) S. BLAIR HEDGES Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University, 208 Mueller Lab, University Park, PA 16802, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Skinks are usually grouped in a single family, Scincidae (1,579 species) representing one-quarter of all lizard species. Oth- er large lizard families, such as Gekkonidae (s.l.) and Iguanidae (s.l.), have been partitioned into multiple families in recent years, based mainly on evidence from molecular phylogenies. Subfamilies and informal suprageneric groups have been used for skinks, defined by morphological traits and supported increasingly by molecular phylogenies. Recently, a seven- family classification for skinks was proposed to replace that largely informal classification, create more manageable taxa, and faciliate systematic research on skinks. Those families are Acontidae (26 sp.), Egerniidae (58 sp.), Eugongylidae (418 sp.), Lygosomidae (52 sp.), Mabuyidae (190 sp.), Sphenomorphidae (546 sp.), and Scincidae (273 sp.). Representatives of 125 (84%) of the 154 genera of skinks are available in the public sequence databases and have been placed in molecular phylogenies that support the recognition of these families. However, two other molecular clades with species that have long been considered distinctive morphologically belong to two new families described here, Ristellidae fam. nov. (14 sp.) and Ateuchosauridae fam. nov. -

Indigenous Terrestrial and Wetland Ecosystems of Auckland

Indigenous terrestrial and wetland ecosystems of Auckland Recommended citation: Singers, N.; Osborne, B.; Lovegrove, T.; Jamieson, A.; Boow, J.; Sawyer, J.; Hill, K.; Andrews, J.; Hill, S.; Webb, C. 2017. Indigenous terrestrial and wetland ecosystems of Auckland. Auckland Council. Cover image: Forest understorey on the Kohukohunui Track, Hunua Ranges. Jason Hosking. ISBN 978-0-9941351-6-2 (Print) ISBN 978-0-9941351-7-9 (PDF) © Auckland Council, 2017. All photographs are copyright of the respective photographer. Indigenous terrestrial and wetland ecosystems of Auckland Singers, N.; Osborne, B.; Lovegrove, T.; Jamieson, A.; Boow, J.; Sawyer, J.; Hill, K.; Andrews, J.; Hill, S.; Webb, C. Edited by Jane Connor. 2017. 3 This guide is dedicated to John Sawyer whose vision initiated the project and who made a substantial contribution to the publication prior to leaving New Zealand. Sadly, John passed away in 2015. John was passionate about biodiversity conservation and brought huge energy and determination to the projects he was involved with. He was generous with his time, knowledge and support for his many friends and colleagues. INDIGENOUS TERRESTRIAL AND WETLAND ECOSYSTEMS OF AUCKLAND Contents Indigenous terrestrial and wetland ecosystems of Auckland Introduction 7 Origins of a national ecosystem classification system 10 Mapping Auckland’s ecosystems 10 Threatened ecosystems 11 Threatened ecosystem assessments in Auckland 11 Introduction to the ecosystem descriptions 13 Forest ecosystems 15 WF4: Pōhutukawa, pūriri, broadleaved forest [Coastal -

Quantifying the Benefits of Rat Eradication to Lizard Populations on Kapiti Island

Quantifying the Benefits of Rat Eradication to Lizard Populations on Kapiti Island A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Conservation Biology Massey University, Palmerston North New Zealand Jennifer Fleur Gollin 2016 i Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ii Abstract In New Zealand the introduction of mammalian predators and human modification of habitat has led to the reduction and extinction of many native species. Therefore an essential part conservation management is the assessment and reduction of exotic predator effects. Many lizard species in New Zealand are threatened, and the eradications of exotic predators from islands has aided in the recovery of many species. Where comparisons can be made on islands before and after rat eradication this can provide a unique opportunity to quantify the benefit of these actions. In 1994–1996 research was carried out on Kapiti Island by Gorman (1996) prior to the eradication of kiore (Rattus exulans) and Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus). This involved sampling six defined habitats using five methods in order to establish density data for lizard species present, as well as recording data on vegetation and weather. In the summer of 2014–2015 I repeated this research using pitfall traps, spotlighting and daytime searching to sample five habitats along pitfall trap lines and transects established by Gorman (1996).