The Popularization of Chemistry in the Netherlands During the Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

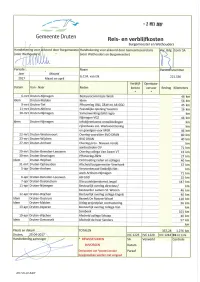

Declaratie G.C.M. Van Elk 2017-03 En 04.Pdf

./7 - 2 fhifil NV Gemeente Druten Reis- en verblijfkosten Burgemeester en Wethouders Handtekening voor kkoord door Burgemeester Handtekening voor akkoord door Gemeentesecretaris . Bdg Contr SA - (voor Weth u e s) / (voor Wethouders en Burgemeester) I Periode \., Naam J snumnier Jaar Maand G.C.M. van Elk 221.536 2017 Maart en april Verblijf- Openbaar Datum Van - Naar Reden kosten vervoer Bedrag Kilometers 6-mrt Druten-Nijmegen Bestuurscommissie Werk 46 km Idem Druten-Malden Idem 56 km 9-mrt Druten-Tiel Pfhoverleg O&J, Z&W en AB GGD 45 km 11-mrt Druten-Altforst Feestelijke opening Yasemin 16 km 20-mrt Druten-Nijmegen Samenwerkingstafel regio km Nijmegen-VGZ 46 km Idem Druten-Nijmegen Infobijeenkomst ontwikkelingen km rijksniveau soc. Werkvoorziening km en gevolgen voor MGR 46 km 22-mrt Druten-Westervoort Overleg voorzitter BVO DRAN 80 km 23-mrt Druten-Wijchen BVO DRAN 40 km 27-mrt Druten-Arnhem Overleg prov. Nieuwe ronde km aanbesteden OV 71 km 29-mrt Druten-Beneden-Leeuwen Overleg collega Van Swam VT 15 km 30-mrt Druten-Beuningen Pfhoverleg Z&W 27 km Idem Druten-Wijchen Ontmoeting raden en colleges 40 km 31-mrt Druten-Opheusden Afscheid burgemeester Veerhoek 57 km 5-apr Druten-Arnhem Vervoerberaad Stedelijk Net- km werk Arnhem-Nijmegen 71 km 6-apr Druten-Beneden-Leeuwen AB GGD 15 km 7-apr Druten-Doetinchem Discussiebijeenkomst Jeugd 147 km 11-apr Druten-Nijmegen Bestuurlijk overleg directeur/ km bestuurder Lamers St. Wonen 46 km 12-apr Druten-Wijchen Bestuurlijk overleg collega Engels 40 km Idem Druten-Oostrum Bezoek De Rooyse Wissel 118 km Idem Druten-Malden Uitleg projectplan contractering 56 km 13-apr Druten-Asperen Bestuurlijk overleg collega Van km Sambeek 101 km 19-apr Druten-Wijchen Afscheid collega Schaap 40 km Idem Druten-Overasselt Afscheid de heer Sanders 57 km km Plaats en datum TOTALEN 357,28 1.276 km Druten, (25-04-2017'. -

16192047.Pdf

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/107599 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-06 and may be subject to change. / : DE MISSIE ACTIE IN NEDERLAND (± 1600 1940) DOOR A. J. J. M. VAN DEN EERENBEEMT MISSIONARIS VAN SCHEUT 1945 UITGEVERIJ J. J. BERKHOUT. NIJMEGEN У DE MISSIE-ACTIE IN NEDERLAND Í PROMOTOR: PROF. DR ALPH. MULDERS N.V. CENTRALE DRUKKERIJ — NIJMEGEN DE MISSIE-ACTIE IN NEDERLAND (± 1600-1940) ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT TER VER- KRIJGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR IN DE H. GODGELEERDHEID AAN DE R.K. UNIVERSITEIT TE NIJMEGEN, OP GEZAG VAN DEN RECTOR MAGNIFICUS Prof. Dr. J. D. M. CORNELISSEN, HOOGLERAAR IN DE FACULTEIT DER LETTEREN EN WIJSBE GEERTE, VOLGENS BESLUIT VAN DE SE NAAT IN HET OPENBAAR TE VERDEDIGEN OP VRIJDAG 14 DECEMBER 1945, DES NA MIDDAGS TE 3.45 UUR PRECIES DOOR. ANDREAS JOANNES JOSEPHUS MARIA VAN DEN EERENBEEMT. MISSIONARIS VAN SCHEUT GEBOREN TE 'S-HERTOGENBOSCH 1945 UITGEVERIJ J. J. BERKHOUT - NIJMEGEN Aan mijn Vader en aan de nagedachtenis van mijn Moeder \ VOORWOORD Nederland bekleedt een vooraanstaande plaats in de wereldomvat tende piissieactie der Heilige Kerk. Verschillende pausen prezen de Nederlandse katholieken om hun missieliefde en missieijver. Gezag volle sprekers gewaagden herhaaldelijk van „Neerlandia docet" op het gebied van missieactie. Zijn we dan niet gerechtigd pns af te vragen : Vanwaar die missie ijver en missiebelangstelling bij de Nederlandse katholieken ? Hoe is die ijver ontstaan en hoe heeft hij zich ontwikkeld ? Langs welke wegen is men moeten gaan om de resultaten, welke we nu opmerken, te be reiken? Met welke moeilijkheden wellicht had men te kampen? Deze studie wil een antwoord geven op deze vragen. -

Indeling Van Nederland in 40 COROP-Gebieden Gemeentelijke Indeling Van Nederland Op 1 Januari 2019

Indeling van Nederland in 40 COROP-gebieden Gemeentelijke indeling van Nederland op 1 januari 2019 Legenda COROP-grens Het Hogeland Schiermonnikoog Gemeentegrens Ameland Woonkern Terschelling Het Hogeland 02 Noardeast-Fryslân Loppersum Appingedam Delfzijl Dantumadiel 03 Achtkarspelen Vlieland Waadhoeke 04 Westerkwartier GRONINGEN Midden-Groningen Oldambt Tytsjerksteradiel Harlingen LEEUWARDEN Smallingerland Veendam Westerwolde Noordenveld Tynaarlo Pekela Texel Opsterland Súdwest-Fryslân 01 06 Assen Aa en Hunze Stadskanaal Ooststellingwerf 05 07 Heerenveen Den Helder Borger-Odoorn De Fryske Marren Weststellingwerf Midden-Drenthe Hollands Westerveld Kroon Schagen 08 18 Steenwijkerland EMMEN 09 Coevorden Hoogeveen Medemblik Enkhuizen Opmeer Noordoostpolder Langedijk Stede Broec Meppel Heerhugowaard Bergen Drechterland Urk De Wolden Hoorn Koggenland 19 Staphorst Heiloo ALKMAAR Zwartewaterland Hardenberg Castricum Beemster Kampen 10 Edam- Volendam Uitgeest 40 ZWOLLE Ommen Heemskerk Dalfsen Wormerland Purmerend Dronten Beverwijk Lelystad 22 Hattem ZAANSTAD Twenterand 20 Oostzaan Waterland Oldebroek Velsen Landsmeer Tubbergen Bloemendaal Elburg Heerde Dinkelland Raalte 21 HAARLEM AMSTERDAM Zandvoort ALMERE Hellendoorn Almelo Heemstede Zeewolde Wierden 23 Diemen Harderwijk Nunspeet Olst- Wijhe 11 Losser Epe Borne HAARLEMMERMEER Gooise Oldenzaal Weesp Hillegom Meren Rijssen-Holten Ouder- Amstel Huizen Ermelo Amstelveen Blaricum Noordwijk Deventer 12 Hengelo Lisse Aalsmeer 24 Eemnes Laren Putten 25 Uithoorn Wijdemeren Bunschoten Hof van Voorst Teylingen -

Wet Op De Veiligheidsregio 2010

Staatsblad van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden Jaargang 2010 0 145 Wet van 11 februari 2010, houdende bepalingen over de brandweerzorg, de rampenbestrijding, de crisisbeheersing en de geneeskundige hulpverlening (Wet veiligheidsregio’s) Wij Beatrix, bij de gratie Gods, Koningin der Nederlanden, Prinses van Oranje-Nassau, enz. enz. enz. Allen, die deze zullen zien of horen lezen, saluut! doen te weten: Alzo Wij in overweging genomen hebben, dat het wenselijk is om de brandweerzorg, de rampenbestrijding, de crisisbeheersing en de geneeskundige hulpverlening, met behoud van lokale verankering bestuurlijk en operationeel op regionaal niveau te integreren, teneinde een doelmatige en slagvaardige hulpverlening te verzekeren, mede op basis van een gecoördineerde voorbereiding, en daartoe veiligheidsre- gio’s in te stellen; Zo is het, dat Wij, de Raad van State gehoord, en met gemeen overleg der Staten-Generaal, hebben goedgevonden en verstaan, gelijk Wij goedvinden en verstaan bij deze: § 1 Algemene bepalingen Artikel 1 In deze wet en de daarop rustende bepalingen wordt verstaan onder: Onze Minister: Onze Minister van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksre- laties; veiligheidsregio: een openbaar lichaam als bedoeld in artikel 9; ramp: een zwaar ongeval of een andere gebeurtenis waarbij het leven en de gezondheid van veel personen, het milieu of grote materiële belangen in ernstige mate zijn geschaad of worden bedreigd en waarbij een gecoördineerde inzet van diensten of organisaties van verschillende disciplines is vereist om de dreiging weg te nemen -

2009-04-06 Toegankelijkheid Gemeentes Volledig

ID_BUSH_PL GEMEENTE KERN HALTENAAM 1.152 Barneveld Barneveld Station Centrum 11.013 Bronckhorst Vorden Horsterkamp Zuid 8.095 Bronckhorst Vorden Station 10.669 Bronckhorst Vorden Station 1.911 Bronckhorst Zelhem Markt 10.552 Bronckhorst Zelhem Markt 815 Brummen Eerbeek Loubergweg 6.063 Brummen Eerbeek Loubergweg 812 Brummen Eerbeek Ringlaan 6.056 Brummen Eerbeek Ringlaan 813 Brummen Eerbeek Vondellaan 6.057 Brummen Eerbeek Vondellaan 8.452 Doetinchem Doetinchem Slingeland Ziekenhuis 8.577 Druten buitengebied Koningstraat 9.695 Druten buitengebied Scharrenburg/N322 9.694 Druten buitengebied Scharrenburg/N322 15.238 Druten Deest Grotestraat 13.312 Druten Druten Busstation 9.702 Druten Druten Busstation 13.587 Druten Druten Busstation 9.688 Druten Druten Hermes Garage 9.685 Druten Druten Markt 9.686 Druten Druten Markt 9.683 Druten Druten Pax Christi College 9.689 Druten Druten Pax Christi College 6.185 Ede Ede Bovenbuurtweg 6.184 Ede Ede Bovenbuurtweg 13.569 Ede Ede Ede / Wageningen Zd 9.988 Ede Ede Stadspoort 6.326 Ede Ede Stadspoort 10.633 Ede Ede Zkh Gelderse Vallei 10.634 Ede Ede Zkh Gelderse Vallei 2.325 Elburg Elburg Centrum 2.328 Elburg Elburg Coragestraat 2.334 Elburg Elburg Het Nieuwe Feithenhof 8.469 Elburg Elburg Het Nieuwe Feithenhof 2.324 Elburg Elburg Molendorp 8.467 Elburg Elburg Zwolscheweg 2.329 Elburg Oostendorp Klokbekerweg 8.464 Elburg Oostendorp Klokbekerweg 2.530 Ermelo Ermelo Hamburgerweg 6.457 Ermelo Ermelo Hamburgerweg 2.486 Lochem Harfsen School 2.487 Lochem Harfsen School 3.508 Neder-Betuwe Kesteren Station 2.622 Nijkerk Nijkerk Station NS 6.442 Nijkerk Nijkerk Station NS 2.611 Nijkerk Nijkerk Tinbergenlaan 6.438 Nijkerk Nijkerk Tinbergenlaan 2.613 Nijkerk Nijkerk Van Renselaerstraat 6.439 Nijkerk Nijkerk Van Renselaerstraat 6.453 Nijkerk Nijkerk Zilverschoon 2.615 Nijkerk Nijkerk Zilverschoon 6.436 Nijkerk Nijkerkerveen Centrum 2.605 Nijkerk Nijkerkerveen Centrum 1.217 Nunspeet Elspeet Centrum 10.333 Nunspeet Nunspeet Boterdijk 2.267 Oldebroek Wezep W. -

Poultry Meat in the Netherlands

Table of contents | 1 Product Boards for Poultry (meat) .................. 38 Livestock, Meat and Eggs ......... 2 Sales structure of the broiler sector 39 Levies and expenditure 3 Broiler slaughterhouses and farms 40 Producer prices and production 41 Livestock, meat and eggs in the Exports of chicken, broiler and turkey meat 42 Netherlands..................... 4 Exports of poultry meat 43 Production value 5 Employment 6 Eggs and egg products .......... 44 Meat and egg consumption 7 Sales structure of the laying hen sector 45 Consumption 8 Egg packing stations 46 Exports of livestock, meat and eggs 9 Laying hen population and Sales outlets of meat and meat products 10 number of farms 47 Range of meat and meat products 11 Producer prices of eggs production 47 Exports of eggs 48 Cattle ......................... 12 Exports of egg products 49 Sales structure of the cattle sector 13 Household purchases of eggs 49 Cattle slaughterhouses and cattle farms 14 Population 15 Meat-processing industry ....... 50 Slaughterhouse listing of bulls 15 Bacon producers 52 Slaughterhouse listing of cows 16 Exports of bacon, meat products 53 The cattle sector’s exports 16 Beef exports 17 Organisations .................. 54 Veal calves .................... 18 Sales structure of the veal calf sector 19 Calf slaughterhouses and calf farms 20 Calf population and housing 21 Veal listing and veal exports 22 The calf sector’s exports 23 Pigs .......................... 24 Sales structure of the pig sector 25 Pig slaughterhouses and pig farms 26 Pig population and slaughterhouses 27 Structure of the pig sector 28 Distribution of carcass meat percentages 29 Proceeds of clean pigs 30 The pig sector’s exports 31 Sheep and goats............... -

Subsidieregister Maart 2021

Subsidieregister van de provincie Gelderland maart 2021 Besluiten onder € 125.000,- in mandaat afdeling en reeds genomen besluiten door PS Programma omschrijving Zaaknummer Project Subsidieontvanger Verleende subsidie Aanpak Invasieve exoten 2020-018790 Aanpak Invasieve exoten Maasdriel Gemeente Maasdriel € 10.000,00 2021-000629 Aanpak invasieve exoten Zaltbommel Gemeente Zaltbommel € 10.000,00 Aanpassingen gemeenschapsvoorziening 2020-018180 Rapiditas multifunctioneel (Nijmegen) Tennisvereniging Rapiditas € 18.488,00 2021-000876 Verduurzaming Stichting Het Tweede Huis (deel 2) (Nederasselt) Stichting het Tweede Huis € 12.926,00 2021-001566 Subsidie Ons Huus Buurtvereniging "Hoge Enk" € 31.975,00 Beheersubsidies Natuur en Landschap (SNL) 2020-014972 Subsidieverlening SNL 2016 beheerperiode 2021-2026 Bosgroepen Stichting Beheer Derdengelden Bosgroepen € 1.303.468,00 Briskr Health & High Tech Accelerator 2021-002686 Briskr Health & High Tech Accelerator (Apeldoorn) Ontwikkelingsmaatschappij Oost Nederland N.V. € 500.000,00 Buurtbus 2021-002607 Subsidie buurtbussen Barneveld-Nijkerk Buurtbus comm. Barneveld-Nijkerk € 67.500,00 CenE Functioneel gebruik erfgoed 2020-018157 Voormalige Pastorie Zieuwent (Zieuwent) Johannes Vastgoed B.V. € 425.455,00 2020-018254 Adelaerthoeve (Arnhem) B&B Adelaerthoeve € 458.608,00 2021-001464 Restauratie Pieter Maarschalkerweerd orgel Rumpts Kerkje (Rumpt) Rumpts Kerkje € 37.686,00 CenE Gemeentelijke monumenten 2020-014888 Instandhoudingssubsidie monumenten Berg en Dal 2021 Gemeente Berg en Dal € 39.000,00 2020-014984 -

Comparing Municipalities: Who Is Your Partner in Crime?

Universiteit Leiden ICT in Business Comparing Municipalities: Who is your partner in crime? Name: Thijs van der Velden Student-no: s1645676 Date: 17/08/2017 1st supervisor: Dr. Cor Veenman 2nd supervisor: Prof. Dr. Aske Plaat MASTER'S THESIS Leiden Institute of Advanced Computer Science (LIACS) Leiden University Niels Bohrweg 1 2333 CA Leiden The Netherlands Master's Thesis Comparing Municipalities: Who is your partner in crime? Supervisor: Author: Dr. Cor Veenman Thijs van der Velden 2nd Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Aske Plaat Abstract In the Netherlands, each municipality is strongly encouraged to write an Integral Safety Plan (ISP). An ISP is a document that contains problems, goals, and priorities related to safety. This research proposes a method to select an effective and relevant ISP for a municipality out of all available ISPs. It focused on the ISPs of the 390 municipalities in the Netherlands, and aimed to determine ways to assist/support a new written ISP by suggesting relevant ISPs to municipalities in order to learn effective methods from the suggested ISPs. This was done by scoring all currently existing ISP's to get the best performing plans, focusing on crime statistics. Two dimension-reduction techniques were applied to descriptive statistics of the municipalities, and the best performing technique (t-SNE) was used. The municipalities were then clustered with K-means in the t-SNE space to retrieve groups of similar municipalities. In addition, k-nearest neighbor algorithm was used to find the K most similar municipalities from a starting point. This research showed a solution to score ISPs and two solutions to find similar municipalities in order to suggest relevant ISPs. -

Factsheet Zon-PV Arnhem-Nijmegen PDF Document

Factsheet zon-PV per RES-regio Regio Arnhem-Nijmegen Totaaloverzicht Opgesteld vermogen in de regio (in MWp) Per gemeente eind 2019* (in MWp) (In MWp per 1000 huishoudens) 20 Arnhem 33 Arnhem 0,4 8 Berg en Dal Berg en Dal 0,8 220 12 6 Beuningen 9 Beuningen 0,8 2 Doesburg 3 Doesburg 0,5 4 Druten 7 Druten 0,8 6 Duiven 14 Duiven 1,3 148 5 141 Heumen 7 Heumen 1,0 12 Lingewaard 18 Lingewaard 0,9 27 Nijmegen 39 Nijmegen 0,5 93 97 11 Overbetuwe 19 Overbetuwe 0,9 7 Renkum 8 Renkum 0,6 68 64 7 Rheden 12 Rheden 0,6 48 48 0 34 37 Rozendaal 1 Rozendaal 1,1 27 3 21 0,5 16 Westervoort 4 Westervoort 6 7 11 Wijchen 17 Wijchen 0,9 10 Zevenaar 18 Zevenaar 0,9 * *(per einde van het kalenderjaar) , , , , Woningen Totaal Woningen Totaal Gemiddeld in Nederland: 0,9 Bron: CBS – Zonnestroom: opgesteld vermogen *voorlopige cijfers SDE+ projecten Verdeling naar opstelling van gerealiseerde sde+ projecten (in MWp) Vermogen van SDE+ projecten die nog in de Gemiddeld in Nederland: 63% SDE+ gerealiseerd op daken pijplijn zitten (in MWp) 29 Arnhem 85% Arnhem 43 8 Berg en Dal 100% Berg en Dal 8 8 Beuningen 44% Beuningen 8 1 Doesburg 100% Doesburg 1 49 Druten 100% Druten 49 11 Duiven 75% Duiven 11 3 Heumen 100% Heumen 3 14 Lingewaard 34% Lingewaard 14 35 Nijmegen 91% Nijmegen 89 43 Overbetuwe 100% Overbetuwe 148 3 Renkum 100% Renkum 3 7 Rheden 100% Rheden 10 ? Rozendaal 100% Rozendaal ? 1 Westervoort 100% Westervoort 1 16 Wijchen 100% Wijchen 30 45 Zevenaar 100% Zevenaar 54 % % % % % % Op daken Op de grond Op daken Totaal Bron: RVO.nl – SDE+ projecten in beheer (peildatum: 22 september 2020) blad 1/2 Factsheet zon-PV per RES-regio Regio Arnhem-Nijmegen Potentieel Congestiegebieden teruglevering in de regio Zie kaart Liander hieronder (29 oktober 2020)1 geen transportcapaciteit beschikbaar zeer beperkt transportcapaciteit beschikbaar beperkt transportcapaciteit beschikbaar transportcapaciteit beschikbaar Let op: controleer de website van Liander voor eventuele nieuwe versies van de kaart. -

Bijlage: Inventarisatie

BIJLAGE: INVENTARISATIE “Op weg naar een bereikbaarheidsaanpak regio Arnhem Nijmegen” Dit is de bijlage die behoort bij de brochure: “Op weg naar een Bereikbaarheidsaanpak Regio Arnhem Nijmegen” COLOFON 2 Deze bijlage is het inventarisatierapport. Hierin staan alle maatregelen die tijdens gesprekken met de gemeenten in de regio Arnhem Nijmegen zijn benoemd. Deze bijlage kent de volgende inhoud: • De toelichting van het onderzoek; • De uitkomsten van de gespreksronden gehouden in de periode maart 2017 en topprioriteiten uitgesproken tijdens de bijeenkomst contactambtenaren mobiliteit (18 april 2017); • De samenhang met de eerdere regiodag mobiliteit (november 2016). INHOUD 3 Bereikbaarheid is een absolute voorwaarde voor de economische positie van de regio Arnhem Nijmegen en het functioneren van de economische kerngebieden. Dit is onderschreven in het bestuursakkoord Investeringsagenda Stedelijk Netwerk Arnhem Nijmegen/ Gelderland. Hierbij ligt de focus op het samenwerken op drie icoonprogramma’s waarin bereikbaarheid een randvoorwaarde is. Parallel hieraan werken de 19 samenwerkende gemeenten in de regio aan het investeren in bereikbaarheid. Er wordt samengewerkt aan een regionale agenda Mobiliteit met als doel het versterken van de ruimtelijk-economische structuur van de stedelijke regio Arnhem Nijmegen. Als eerste stap richting de regionale agenda Mobiliteit is een inventarisatie verricht naar de onderwerpen die regionaal van belang zijn op het gebied van mobiliteit om samen met de partners uit te werken. TOELICHTING 4 . Gesprekken: 1) Gemeenten in de Liemers 19 gemeenten 2) Doesburg, Rheden, Rozendaal 3) Arnhem en Renkum 4) Overbetuwe en Lingewaard 5) Nijmegen 9 gesprekken 6) Berg en Dal 7) Mook en Middelaar en Heumen 8) Druten, Beuningen en Wijchen TOELICHTING 9) Organisatie BBV/ Gelderland 5 . -

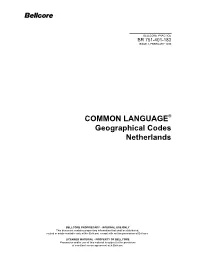

Geographical Codes Netherlands

BELLCORE PRACTICE BR 751-401-183 ISSUE 8, FEBRUARY 1999 COMMON LANGUAGE® Geographical Codes Netherlands BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY This document contains proprietary information that shall be distributed, routed or made available only within Bellcore, except with written permission of Bellcore. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE Possession and/or use of this material is subject to the provisions of a written license agreement with Bellcore. Geographical Codes Netherlands BR 751-401-183 Copyright Page Issue 8, February 1999 Prepared for Bellcore by: R. Keller For further information, please contact: R. Keller (732) 699-5330 To obtain copies of this document, Regional Company/BCC personnel should contact their company’s document coordinator; Bellcore personnel should call (732) 699-5802. Copyright 1999 Bellcore. All rights reserved. Project funding year: 1999. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. ii LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE BR 751-401-183 Geographical Codes Netherlands Issue 8, February 1999 Trademark Acknowledgements Trademark Acknowledgements COMMON LANGUAGE is a registered trademark and CLLI is a trademark of Bellcore. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE iii Geographical Codes Netherlands BR 751-401-183 Trademark Acknowledgements Issue 8, February 1999 BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. iv LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY -

CEF Telecom Call 2014 – Electronic Identification and Authentication CEF-TC-2014-3

ANNEX I LIST OF SELECTED PROPOSALS Connecting Europe Facility Call for proposals: CEF Telecom Call 2014 – Electronic Identification and Authentication CEF-TC-2014-3 Proposal Title of proposal Applicant(s) Maximum Code grant amount (€) 2014-ES- Setting up of an eIDAS Ministerio de Hacienda y Administraciones Publicas 50,000 IM-0009 compliant PEPS in Spain 2014-ES- Operation of the Spanish Ministerio de Hacienda y Administraciones Publicas 150,000 IM-0010 Pan-European Proxy Services for the first years 2014-NL- "eIDAS 2018 for Gemeente Brielle/ Gemeente Nissewaard/ Gemeente 1,440,000 IM-0020 Municipalities"; Action type Westvoorne/ Gemeenschappelijke Regeling Werk & iii: Integration in an existing Inkomen Lekstroom/ Gemeente Almelo/ Gemeente Ede/ online platform of this eID Gemeente Haarlemmerliede en Spaarnwoude/ DSI in order to enable citizens Gemeente Heemskerk/ Gemeente Heerhugowaard/ from any Member State to Gemeente Hillegom / Gemeente Houten / Gemeente use its national eID to access Aalburg / Gemeente Achtkarspelen / Gemeente Deurne / a public service. Gemeente Druten / Werkorganisatie Duivenvoorde / Gemeente Eersel / Gemeente Hardinxveld-Giessendam / Gemeente Haren / Gemeente ISHW / Gemeente Leudal / Gemeente Lingewaal / Gemeente Nunspeet / Gemeente Nuth / Gemeente Oirschot / Gemeente Ooststellingwerf / Gemeente Opmeer / Gemeente Renswoude / Gemeente Reusel de Mierden / Gemeente Staphorst / Gemeente Twenterand / Gemeente Tytsjerksteradiel / The Kingdom of the Netherlands, Ministry of Economic Affairs (NL-MEA) / Gemeente Utrechtse