Barr, Richard (1917-1989) by David Crespy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horton Foote

38th Season • 373rd Production MAINSTAGE / MARCH 29 THROUGH MAY 5, 2002 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing Artistic Director Artistic Director presents the World Premiere of by HORTON FOOTE Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Composer MICHAEL DEVINE MAGGIE MORGAN TOM RUZIKA DENNIS MCCARTHY Dramaturgs Production Manager Stage Manager JENNIFER KIGER/LINDA S. BAITY TOM ABERGER *RANDALL K. LUM Directed by MARTIN BENSON Honorary Producers JEAN AND TIM WEISS, AT&T: ONSTAGE ADMINISTERED BY THEATRE COMMUNICATIONS GROUP PERFORMING ARTS NETWORK / SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P - 1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Constance ................................................................................................... *Annie LaRussa Laverne .................................................................................................... *Jennifer Parsons Mae ............................................................................................................ *Barbara Roberts Frankie ...................................................................................................... *Juliana Donald Fred ............................................................................................................... *Joel Anderson Georgia Dale ............................................................................................ *Linda Gehringer S.P. ............................................................................................................... *Hal Landon Jr. Mrs. Willis ....................................................................................................... -

Sam Shepard One Acts: War in Heaven (Angel’S Monologue), the Curse of the Raven’S Black Feather, Hail from Nowhere, Just Space Rhythm

Sam Shepard One Acts: War in Heaven (Angel’s Monologue), The Curse of the Raven’s Black Feather, Hail from Nowhere, Just Space Rhythm Resource Guide for Teachers Created by: Lauren Bloom Hanover, Director of Education 1 Table of Contents About Profile Theatre 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 The Artists 5 Lesson 1: Who is Sam Shepard? Classroom Activities: 1) Biography and Context 6 2) Shepard in His Own Words 6 3) Shepard Adjectives 7 Lesson 2: Influences on Shepard Classroom Activities 1) Exploring Similar Themes in O’Neill and Shepard 16 2) Exploring Similar Styles in Beckett and Shepard 17 3) Exploring the Influence of Music on Shepard 18 Lesson 3: Inspired by Shepard Classroom Activities 1) Reading Samples of Shepard 28 2) Creative Writing Inspired by Shepard 29 3) Directing One’s Own Work 29 Lesson 4: What Are You Seeing Classroom Activities 1) Pieces Being Performed 33 2) Statues 34 3) Staging a Monologue 36 Lesson 5: Reflection Classroom Activities 1) Written Reflection 44 2) Putting It All Together 45 2 About Profile Theatre Profile Theatre was founded in 1997 with the mission of celebrating the playwright’s contribution to live theater. To that end, Profile programs a full season of the work of a single playwright. This provides our community with the opportunity to deeply engage with the work of our featured playwright through performances, readings, lectures and talkbacks, a unique experience in Portland. Our Mission realized... Profile invites our audiences to enter a writer’s world for a full season of plays and events. -

A Delicate Balance

PEEK BEHIND THE SCENES OF A DELICATE BALANCE Compiled By Lotta Löfgren To Our Patrons Most of us who attend a theatrical performance know little about how a play is actually born to the stage. We only sit in our seats and admire the magic of theater. But the birthing process involves a long period of gestation. Certainly magic does happen on the stage, minute to minute, and night after night. But the magic that theatergoers experience when they see a play is made possible only because of many weeks of work and the remarkable dedication of many, many volunteers in order to transform the text into performance, to move from page to stage. In this study guide, we want to give you some idea of what goes into creating a show. You will see the actors work their magic in the performance tonight. But they could not do their job without the work of others. Inside you will find comments from the director, the assistant director, the producer, the stage manager, the set -

T Wentieth Centur Y North Amer Ican Drama

TWENTIETH CENTURY NORTH AMERICAN DRAMA, SECOND EDITION learn more at at learn more alexanderstreet.com Twentieth Century North American Drama, Second Edition Twentieth Century North American Drama, Second Edition contains 1,900 plays from the United States and Canada. In addition to providing a comprehensive full-text resource for students in the performing arts, the collection offers a unique window into the econom- ic, historical, social, and political psyche of two countries. Scholars and students who use the database will have a new way to study the signal events of the twentieth century – including the Depression, the role of women, the Cold War, and more – through the plays and performances of writers who lived through these decades. More than 1,250 of the works are in copyright and licensed Jules Feiffer, Neil LaBute, Moisés Kaufman, Lee Breuer, Richard from the authors or their estates, and 1,700 plays appear in Foreman, Stephen Adly Guirgis, Horton Foote, Romulus Linney, no other Alexander Street collection. At least 550 of the works David Mamet, Craig Wright, Kenneth Lonergan, David Ives, Tina have never been published before, in any format, and are Howe, Lanford Wilson, Spalding Gray, Anna Deavere Smith, Don available only in Twentieth Century North American Drama, DeLillo, David Rabe, Theresa Rebeck, David Henry Hwang, and Second Edition – including unpublished plays by major writers Maria Irene Fornes. and Pulitzer Prize winners. Besides the mainstream works, users will find a number of plays Important works prior to 1920 are included, with the concentration of particular social significance, such as the “people’s theatre” of works beginning with playwrights such as Eugene O’Neill, exemplified in performances by The Living Theatre and The Open Elmer Rice, Sophie Treadwell, and Susan Glaspell in the 1920s Theatre. -

Theatre & Performance

CONTEMPORARY Theatre & Performance MULTICULTURALISM/ DIVERSITY • African-American Theatre • Global Theatre • LGBTQ • Performance • Asian-American • Performance Art Theatre • Experimental Theatre • Latino Theatre (LATC) AFRICAN-AMERICAN THEATRE • August Wilson (1945-2005) - Fences (1987) • Joe Turner’s Come and Gone (1988) • The Piano Lesson (1990) ASIAN-AMERICAN THEATRE • East/West Players (downtown LA) • David Henry Huang - M. Butterfly, Bondage, Yellow Face LGBTQ • Charles Ludlam (19431987) died of AIDS— founded The Ridiculous Theatre Company- The Mystery of Irma Vep (1984) with Everett Quinton • Tony Kushner- Angels in America (1993) • Larry Kramer -The Normal Heart (1985) • Terence McNally - Mothers and Sons (2014) • Split Britches (WOW Cafe)- Beauty and The Beast (1982), Belle Reprieve (1990), Lesbians Who Kill (1992) • The Tectonic Theatre Company (The Laramie Project) • Rent, Hedwig and The Angry Inch, Kinky Boots, Fun Home LATINO THEATRE • LATC (Latino Theatre Company- LA Theatre Center)- founded 1985 by Artistic Director, Jose Luis Valenzuela • Zoot Suit (1979) by Luis Valdez- made into a film (1981) • based on the Sleepy Lagoon Murder Trial (1942) and the Zoot Suit Riots in Los Angeles https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M51xwySGNYc https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dwINn5DEL1c GLOBAL THEATRE • Takarazuka Revue (Drag performance in Japan) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JLy2iOnBnsA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Wccu0JjcLw • Handspring Puppet Company (South Africa) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SqAkQCbuvqg • Chinese Performance (spectacle) -

The Playwright As Filmmaker: History, Theory and Practice, Summary of a Completed Thesis by Portfolio OTHNIEL SMITH, University of Glamorgan

Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol 1, No 2 (2007) ARTICLE The Playwright as Filmmaker: History, Theory and Practice, Summary of a completed thesis by portfolio OTHNIEL SMITH, University of Glamorgan ABSTRACT This paper summarises my doctoral research into the work of dramatists who became filmmakers – specifically Preston Sturges, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, David Mamet, and Neil Labute. I began with the hypothesis that there is something distinctive about the work of filmmakers who have a background in writing for text-based theatre, an arena where the authorship is, on the whole, not a vexatious issue, as is the case in commercial cinema. Through case studies involving textual and contextual analyses of their films, I found common threads linking their work, in respect both of their working methods and their approach to text and performance. From this, I evolved a theoretical position involving the development of a tentative ‘dogme’ designed to smooth the path between writing plays and making films, and produced short no- budget videos illustrating it. KEYWORDS Theatre/film, Dogme, theoretical practice, Mamet, Fassbinder. Introduction The aim of this project – a thesis by portfolio, completed at the now-defunct Film Academy at the University of Glamorgan – was to contribute to that area within film theory where creativity is taken seriously as a field of study; an attempt to reconcile theory with artistry, without attempting to theorise artistry. The ‘theatrical’ is often characterised as the ‘other’ of the cinematic, within both popular and scholarly discourse. My intention was to examines the interface between the two forms, and isolate those aspects of the theatrical aesthetic which can be profitably employed within cinema, looking at the issue from the perspective of the working dramatist – my background being as a writer for theatre, radio and television. -

In Kindergarten with the Author of WIT

re p resenting the american theatre DRAMATISTS by publishing and licensing the works PLAY SERVICE, INC. of new and established playwrights. atpIssuel 4,aFall 1999 y In Kindergarten with the Author of WIT aggie Edson — the celebrated playwright who is so far Off- Broadway, she’s below the Mason-Dixon line — is performing a Mdaily ritual known as Wiggle Down. " Tapping my toe, just tapping my toe" she sings, to the tune of "Singin' in the Rain," before a crowd of kindergarteners at a downtown elementary school in Atlanta. "What a glorious feeling, I'm — nodding my head!" The kids gleefully tap their toes and nod themselves silly as they sing along. "Give yourselves a standing O!" Ms. Edson cries, when the song ends. Her charges scramble to their feet and clap their hands, sending their arms arcing overhead in a giant "O." This willowy 37-year-old woman with tousled brown hair and a big grin couldn't seem more different from Dr. Vivian Bearing, the brilliant, emotionally remote English professor who is the heroine of her play WIT — which has won such unanimous critical acclaim in its small Off- Broadway production. Vivian is a 50-year-old scholar who has devoted her life to the study of John Donne's "Holy Sonnets." When we meet her, she is dying of very placement of a comma crystallizing mysteries of life and death for ovarian cancer. Bald from chemotherapy, she makes her entrance clad Vivian and her audience. For this feat, one critic demanded that Ms. Edson in a hospital gown, dragging an IV pole. -

Sam Shepard's Dramaturgical Strategies Susan

Fall 1988 71 Estrangement and Engagement: Sam Shepard's Dramaturgical Strategies Susan Harris Smith Current scholarship reveals an understandable preoccupation with and confusion over Sam Shepard's most prominent characteristics, his language and imagery, both of which are seminal features of his technical innovation. In their attempts to describe or define Shepard's idiosyncratic dramaturgy, critics variously have called it absurdist, surrealistic, mythic, Brechtian, and even Artaudian. Most critics, too, are concerned primarily with his themes: physical violence, erotic dynamism, and psychological dissolution set against the cultural wasteland of modern America (Marranca, ed.). But in focusing on Shepard's imagery, language, and themes, some critics ignore theatrical performance. Beyond observing that many of Shepard's role-playing characters engage in power struggles with each other, few critics have concerned themselves with Shepard's structural strategies or with the ways in which he manipulates his audience. One who has addressed the issue, Bonnie Marranca, writes: Characters often engage in, "performance": they create roles for themselves and dialogue, structuring new realities. ... It might be called an aesthetics of actualism. In other words, the characters act themselves out, even make them• selves up, through the transforming power of their imagina• tion. An Assistant Professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh and the author of Masks in Modern Drama, Susan Harris Smith is currently working on a book on American drama. A shorter version of this article was presented at the South• eastern Modern Languages Association in 1985. 72 Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism Because the characters are so free of fixed reality, their imagination plays a key role in the narratives. -

Selected Correspondence from the Horton Foote

SELECTED CORRESPONDENCE FROM THE HORTON FOOTE COLLECTION, 1912-1991 by SUSAN CHRISTENSEN Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Horton Foote for his generosity in granting me permission to include transcriptions of his family members’ correspondence in my dissertation. I would also like to thank his daughter Hallie for her kind assistance. I have been fortunate to have the opportunity to work with Dr. Laurin Porter, my supervising professor, an extraordinary teacher, a remarkable scholar, and a generous and thoughtful person. During my graduate studies, her wisdom has inspired me and her encouragement has sustained me. I would like to extend my heartfelt appreciation to the members of my graduate committee, Dr. Desirée Henderson and Dr. Neill Matheson, and also to Dr. Wendy Faris and Dr. Thomas Porter, for their kindness and their work on my behalf. I am grateful to Dr. Russell Martin III, the director of the DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University, and his staff, who assisted me during the many months I spent conducting archival research. Finally, and most importantly, I would like to thank my husband Robert for his unwavering support and love. July 16, 2008 ii ABSTRACT SELECTED CORRESPONDENCE FROM THE HORTON FOOTE COLLECTION, 1912-1991 Susan Christensen, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2008 Supervising Professor: Laurin Porter This dissertation includes a discussion of archival research and editorial procedures employed in the study, introductory essays on the private correspondence of the family of Horton Foote, and transcriptions of one hundred letters selected from the personal correspondence in the Horton Foote Collection reposited in the DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, with extensive annotations and ancillary materials. -

Buried Child by Sam Shepard

MEDIA CONTACT: Bernie Fabig, Marketing & Publicity Manager 310-756-2428 • [email protected] The third production of A Noise Within’s 2019-2020 Season: THEY PLAYED WITH FIRE Buried Child By Sam Shepard Directed by Julia Rodriguez-Elliott Oct. 19 – Nov. 23, 2019 Pasadena, Calif. (Oct. 19, 2019) – A Noise Within (ANW), California’s acclaimed classic repertory theatre company, is proud to present Sam Shepard’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Buried Child, directed by ANW Producing Artistic Director Julia Rodriguez-Elliott. Shepard’s remarkable masterpiece Buried Child will run Oct. 13 through Nov. 23, 2019 with press performances on Saturday, Oct. 19 at 8 p.m. and Sunday, Oct. 20 at 2 p.m. Set in America’s heartland, Sam Shepard’s powerful Pulitzer Prize-winning play details, with wry humor, the disintegration of the American Dream. When 22-year-old Vince unexpectedly shows up at the family farm with his girlfriend Shelly, no one recognizes him. So begins the unraveling of dark secrets. A surprisingly funny look at disillusionment and morality, Shepard’s masterpiece is the family reunion no one anticipated. “Buried Child is wickedly funny,” said Producing Artistic Director Julia Rodriguez-Elliott. “Sam Shepard has an uncanny way of bringing out the humor in dysfunction. There’s something familiar, yet not familiar about this family. It’s at once disconcertingly recognizable and inexplicably strange.” - more - MEDIA CONTACT: Bernie Fabig, Marketing & Publicity Manager 310-756-2428 • [email protected] In Buried Child, comedy meets the absurd in a bizarre twist on the family drama that scorches with a powerful commentary on the “American Dream” and what happens when a community simmers in neglect, resentment, and disowned memory. -

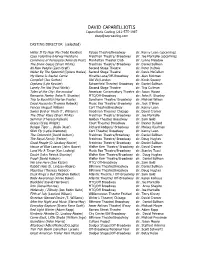

DAVID CAPARELLIOTIS Caparelliotis Casting /212-575-1987 [email protected]

DAVID CAPARELLIOTIS Caparelliotis Casting /212-575-1987 [email protected] CASTING DIRECTOR (selected) Holler If Ya Hear Me (Todd Kreidler) Palace Theatre/Broadway dir. Kenny Leon (upcoming) Casa Valentina (Harvey Fierstein) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Joe Mantello (upcoming) Commons of Pensacola (Amanda Peet) Manhattan Theater Club dir. Lynne Meadow The Snow Geese (Sharr White) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan All New People (Zach Braff) Second Stage Theatre dir. Peter DuBois Water By The Spoonful (Quiara Hudes) Second Stage Theatre dir. Davis McCallum My Name Is Rachel Corrie Minetta Lane/Off-Broadway dir. Alan Rickman Complicit (Joe Sutton) Old Vic/London dir. Kevin Spacey Orphans (Lyle Kessler) Schoenfeld Theatre/ Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan Lonely I’m Not (Paul Weitz) Second Stage Theatre dir. Trip Cullman Tales of the City: the musical American Conservatory Theatre dir: Jason Moore Romantic Poetry (John P. Shanley) MTC/Off-Broadway dir: John P. Shanley Trip to Bountiful (Horton Foote) Sondheim Theatre/ Broadway dir. Michael Wilson Dead Accounts (Theresa Rebeck) Music Box Theatre/ Broadway dir. Jack O’Brien Fences (August Wilson) Cort Theatre/Broadway dir. Kenny Leon Sweet Bird of Youth (T. Williams) Goodman Theatre/ Chicago dir. David Cromer The Other Place (Sharr White) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Joe Mantello Seminar (Theresa Rebeck) Golden Theatre/ Broadway dir. Sam Gold Grace (Craig Wright) Court Theatre/ Broadway dir. Dexter Bullard Bengal Tiger … (Rajiv Josef) Richard Rodgers/ Broadway dir. Moises Kaufman Stick Fly (Lydia Diamond) Cort Theatre/ Broadway dir. Kenny Leon The Columnist (David Auburn) Freidman Theatre/Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan The Royal Family (Ferber) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. -

Newton Grisham Library Play Script List -By Author

Newton Grisham Library Play Script List -by Author BIN # PLAY # TITLE AUTHOR # MEN # WOMEN # CHILDREN OTHER 73 1570 Manhattan Class Company Class 1 Acts 1991-1992 161 2869 The Boys from Siam Connolly, John Austin 2 161 2876 Fugue Thuna, Lee 3 5 74 1591 Acrobatics Aaron, Joyce; Tarlo, Luna 96 1957 June Groom Abbot, Rick 3 6 99 2016 Play On! Abbot, Rick 3 7 103 2080 Turn For The Nurse, A Abbot, Rick 5 5 30 699 Three Men On A Horse Abbott, G. And J.C. Holm 11 4 34 802 Green Julia Ableman, Paul 2 133 2457 Tabletop Ackerman, Rob 5 1 86 1793 Batting Cage, The Ackermann, Joan 1 3 86 1798 Marcus Is Walking Ackermann, Joan 3 2 88 1825 Off The Map Ackermann, Joan 3 2 101 2051 Stanton's Garage Ackermann, Joan 4 4 10 227 Farewell, Farewell Eugene Ackland, Rodney; Vari, John 3 6 84 1776 Lighting Up The Two-Year Old Aerenson, Benjie 3 167 2970 Dark Matters Aguirre-Sacasa, Roberto 3 1 168 2982 King of Shadows Aguirre-Sacasa, Roberto 2 2 169 2998 The Muckle Man Aguirre-Sacasa, Roberto 5 2 169 3007 Rough Magic Aguirre-Sacasa, Roberto 7 5 doubling 101 2054 Edgar Lee Masters' Spoon River Anthology Aidman, Charles 3 2 101 2054 Spoon River Anthology Aidman, Charles [Adapt. By] 3 2 149 2686 Green Card Akalaitis, JoAnne 6 5 10 221 Fragments Albee, Edward 4 4 19 436 Marriage Play Albee, Edward 1 1 26 604 Seascape Albee, Edward 2 2 30 705 Tiny Alice Albee, Edward 4 1 34 800 The Zoo Story and The Sandbox: Two Short Plays Albee, Edward 34 800 Sandbox, The Albee, Edward 3 2 44 1066 Counting the Ways and Listening: Two Plays Albee, Edward 44 1066 Counting The Ways