The Break-Up of the Southwest Conference by Auston Fertak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Coaching Records

FOOTBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) Coaching Records 5 Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) Coaching Records 15 Division II Coaching Records 26 Division III Coaching Records 37 Coaching Honors 50 OVERALL COACHING RECORDS *Active coach. ^Records adjusted by NCAA Committee on Coach (Alma Mater) Infractions. (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. Note: Ties computed as half won and half lost. Includes bowl 25. Henry A. Kean (Fisk 1920) 23 165 33 9 .819 (Kentucky St. 1931-42, Tennessee St. and playoff games. 44-54) 26. *Joe Fincham (Ohio 1988) 21 191 43 0 .816 - (Wittenberg 1996-2016) WINNINGEST COACHES ALL TIME 27. Jock Sutherland (Pittsburgh 1918) 20 144 28 14 .812 (Lafayette 1919-23, Pittsburgh 24-38) By Percentage 28. *Mike Sirianni (Mount Union 1994) 14 128 30 0 .810 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four- (Wash. & Jeff. 2003-16) year NCAA colleges regardless of division. 29. Ron Schipper (Hope 1952) 36 287 67 3 .808 (Central [IA] 1961-96) Coach (Alma Mater) 30. Bob Devaney (Alma 1939) 16 136 30 7 .806 (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. (Wyoming 1957-61, Nebraska 62-72) 1. Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) 27 332 24 3 .929 31. Chuck Broyles (Pittsburg St. 1970) 20 198 47 2 .806 (Mount Union 1986-2012) (Pittsburg St. 1990-2009) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) 13 105 12 5 .881 32. Biggie Munn (Minnesota 1932) 10 71 16 3 .806 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Albright 1935-36, Syracuse 46, Michigan 3. -

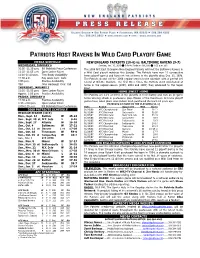

Patriots Host Ravens in Wild Card Playoff Game

PATRIOTS HOST RAVENS IN WILD CARD PLAYOFF GAME MEDIA SCHEDULE NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (10-6) vs. BALTIMORE RAVENS (9-7) WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 6 Sunday, Jan. 10, 2010 ¹ Gillette Stadium (68,756) ¹ 1:00 p.m. EDT 10:50 -11:10 a.m. Bill Belichick Press Conference The 2009 AFC East Champion New England Patriots will host the Baltimore Ravens in 11:10 -11:55 a.m. Open Locker Room a Wild Card playoff matchup this Sunday. The Patriots have won 11 consecutive 11:10-11:20 p.m. Tom Brady Availability home playoff games and have not lost at home in the playoffs since Dec. 31, 1978. 11:30 a.m. Ray Lewis Conf. Calls The Patriots closed out the 2009 regular-season home schedule with a perfect 8-0 1:05 p.m. Practice Availability record at Gillette Stadium. The first three times the Patriots went undefeated at TBA John Harbaugh Conf. Call home in the regular-season (2003, 2004 and 2007) they advanced to the Super THURSDAY, JANUARY 7 Bowl. 11:10 -11:55 p.m. Open Locker Room HOME SWEET HOME Approx. 1:00 p.m. Practice Availability The Patriots are 11-1 at home in the playoffs in their history and own an 11-game FRIDAY, JANUARY 8 home winning streak in postseason play. Eleven of the franchise’s 12 home playoff 11:30 a.m. Practice Availability games have taken place since Robert Kraft purchased the team 16 years ago. 1:15 -2:00 p.m. Open Locker Room PATRIOTS AT HOME IN THE PLAYOFFS (11-1) 2:00-2:15 p.m. -

The Hall of Honor and the Move to Tier One Athletics by Debbie Z

The Hall of Honor and the Move to Tier One Athletics By Debbie Z. Harwell rom its earliest days, the University of Houston rose to Fthe top in athletics—not in football or basketball as you might expect, but in ice hockey. The team competed for the first time in 1934 against Rice Institute in the Polar Wave Ice Rink on McGowan Street. It went undefeated for the season, scoring three goals to every one for its opponents. The next year, only one player returned, but the yearbook reported that they “represented a fighting bunch of puck- pushers.” They must have been because the team had no reserves and played entire games without a break.1 The sports picture changed dramatically in 1946 when the University joined the Lone Star Conference (LSC) and named Harry H. Fouke as athletic director. He added coaches in men’s tennis, golf, track, football, and basketball, and a new director of women’s athletics focused on physical education. Although the golf team took second in confer- The 1934 Houston Junior College ice hockey team, left to right: Nelson ence play and the tennis team ranked fourth, basketball was Hinton, Bob Swor, Lawrence Sauer, Donald Aitken (goalie), Ed the sport that electrified the Cougar fans. The team once Chernosky, Paul Franks, Bill Irwin, Gus Heiss, and Harry Gray. Not practiced with a “total inventory of two basketballs left pictured John Burns, Erwin Barrow, John Staples, and Bill Goggan. Photo from 1934 Houstonian, courtesy of Digital Library, behind by World War II campus Navy recruits, one of them Special Collections, University of Houston Libraries. -

Pilots Story

Daily NewS'Miner, Fairbanks, Alaska, Thursday, August 19,1976-A-13 Paterno, Rush lead list of top coaches BIRMINGHAM, Ala. (AP)-Joc Palerno of Pcnn Stale and Frank Kush of Arizona Slate are the winningcsl active college football coaches among those with al least five seasons as a head coach at a major college. They headed the list in Ihe annual list ol "Top Twenty Coaches" released today by Elmore "Scoop" Hudgins public relations director of the Southeastern Conference, who originated the rankings in 1958. In 10 years at Pcnn State, Paterno Dan Dcvinc of Notre Dame, I27--H-8-- Hudgins compiles the records of all has compiled a record of M-18-1 for a NCAA Division I coaches, to find out .7,'(2; Frank liroylcs of Arkansas, 1«- percentage of .836, well ahead of 57-r>-.711; Carmen Cozza of Yale, G9-29- who have won Ihe most games. Only anyone else on Ihe list. Arizona Stale's service at four-year schools counts and 1-.7(K, and Charlie McClcmlon of 12-0 record last year enabled Kush to Louisiana State, 106--H-6—.699. at least five years must be at the major move into second place past Michigan's college level. The 20 are then listed in Bo Schembechler with a record of 151- The second 10 consists of Florida order of percentage. 39-1 .793. Schembechler is third with Stale's Bobby Bowdcn, Georgia's Vince 10G-26-6-.790. Dooley, Temple's Wayne Hardin, Toqualify for Ihe 1976 honor roll, 69or Florida's Doug Dickey, Illinois' Bob more victories were necessary. -

Colorado's Conference History ALL-TIME CONFERENCE

Colorado’s conference history The Pac-12 Conference is technically the seventh conference in which A decade later, CU athletics would change forever, as the Buffaloes the University of Colorado has been a member. were accepted into the Missouri Valley Intercollegiate Athletic Association There were no organized leagues in the Rocky Mountain region when (also known as the Big Six) on Dec. 1, 1947. Colorado started competition CU started playing football in 1890. In 1893, Colorado was a charter mem- in this league in the 1948-49 school year, thus changing the group’s name ber of the Colorado Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA; also known to the Big Seven. Other schools in the league were Iowa State, Kansas, as the Colorado Football Association), joined by Denver, Colorado College, Kansas State, Missouri, Nebraska and Oklahoma. When Oklahoma State Colorado Mines and Colorado A & M. CU remained a member through rejoined the group after a three decade absence in 1958, the conference 1908 (except 1905, when it withdrew from the state conference prior to became known as the Big Eight. the season). On Feb. 25, 1994, the Big Eight announced expansion plans to include In 1909, a new alignment called the Colorado Faculty Athletic Baylor, Texas, Texas A&M and Texas Tech from the Southwest Conference, Conference came into existence, with CU, CC, A & M and Mines the char- a league plagued with NCAA violations and probations over the previous ter members. One year later in 1910, the name was changed to the Rocky decade; the merger of the four gave those schools a new start in the Mountain Faculty Athletic Conference, as the league expanded geograph- new Big 12. -

Fan's Guide to Big 12 Now on ESPN+

Fan’s Guide to Big 12 Now on ESPN+ Earlier this spring, the Big 12 Conference and ESPN agreed to significantly expand their existing rights agreement, which runs through 2024-25. Under the expanded agreement, hundreds of additional Big 12 sports events annually will be distributed on the Big 12 Now on ESPN+ digital platform. What does this mean for fans? • In football, in addition to the Big 12 games continuing to appear on ABC & ESPN networks or FOX networks, one game per season from the participating programs will be available exclusively on Big 12 Now on ESPN+. • In men’s basketball, all regular season and exhibition games from the eight participating programs that are not distributed on ESPN’s traditional television networks will be available exclusively on Big 12 Now on ESPN+. • Additionally, Big 12 Now on ESPN+ will feature hundreds of events from other sports at the participating programs, including women’s basketball, volleyball, soccer, wrestling, softball, baseball and more. • Select Big 12 Conference Championship events will also be distributed on Big 12 Now on ESPN+. Which Big 12 programs Can I Watch on Big 12 Now on ESPN+? • Eight of the conference’s 10 schools will produce and deliver live athletic events via Big 12 Now on ESPN+. • Starting in 2019, there will be games from Baylor, Kansas, Kansas State and Oklahoma State, in addition to select Big 12 Conference championship events. • In 2020-21, Iowa State, TCU, West Virginia and Texas Tech will join the lineup. • Due to existing long-term rights agreements, Texas (Longhorn Network) and Oklahoma will not produce and deliver programming via Big 12 Now on ESPN+ at this time. -

NCAA Division I Academic Performance Program

REPORT OF THE NCAA DIVISION I STUDENT-ATHLETE ADVISORY COMMITTEE February 10, 2021, VIDEOCONFERENCE KEY ITEMS. • None. INFORMATIONAL ITEMS. 1. Approval of the NCAA Division I Student-Athlete Advisory Committee January 12 and 15, 2021, meeting report. The Division I Student-Athlete Advisory Committee reviewed and approved the report from its January 12 and 15 meeting. 2. NCAA guest speaker. The Student-Athlete Advisory Committee welcomed guest speaker, Derrick Coles, assistant director of NCAA enforcement. Educational information was discussed with the committee regarding agents and agent certifications. 3. Review of Division I Committee on Infractions recommendation. The Student-Athlete Advisory Committee discussed the potential recommendation to adjust the composition of the Division I Committee on Infractions to include a student-athlete representative from Division I SAAC. The committee discussed the overall details of the recommendation and will seek feedback from the appropriate standing committees and key stakeholders. 4. Discuss temporary dead period/recruiting calendars. The Student-Athlete Advisory Committee reviewed a request from the NCAA Division I Council Coordination Committee regarding the current temporary recruiting dead period. The committee indicated its preference to extend the current temporary COVID-19 recruiting dead period beyond April 15 and was supportive of the NCAA Division I Council acting on the extension of the dead period during the February 17, 2021, meeting. The committee noted the importance of providing prospective student-athletes with immediate guidance on the future of recruiting. The committee was not supportive of transitioning to a quiet period on April 16, noting the importance of maintaining the health and safety of current student- athletes that are in season. -

Big 12 Conference

BIG 12 CONFERENCE BIG 12 CONFERENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS 400 East John Carpenter Freeway Irving, TX 75062 GENERAL INFORMATION 469/524-1000 Media Services ___________________________________________2-3 469/524-1045 - Fax Conference Information _____________________________________ 4 Big12Sports.com National Champions & Sportsmanship Statement ___________________ 5 Conference Championships __________________________________ 6 Commissioner __________________________________ Dan Beebe Notebook ______________________________________________ 7 Deputy Commissioner ___________________________ Tim Weiser Phillips 66 Big 12 Championship ______________________________8-9 Senior Associate Commissioner ______________________ Tim Allen Composite Schedule ____________________________________ 10-13 Senior Associate Commissioner ___________________ Dru Hancock NCAA Championship/College World Series _____________________ 14 Associate Commissioner - Communications ____________ Bob Burda Commissioner Dan Beebe & Conference Staff ____________________ 15 Associate Commissioner - Football & Student Services __________________ Edward Stewart TEAMS Baylor Bears __________________________________________ 16-18 Associate Commissioner - Quick Facts/Schedule/Coaching Information ____________________ 16 Men’s Basketball & Game Management ________ John Underwood Alphabetical/Numerical Rosters _____________________________ 17 Chief Financial Officer ____________________________ Steve Pace 2010 Results/Statistics ____________________________________ 18 Assistant Commissioner -

SPERRY Golf Course

Tuesday, February 28, 1956 THE BATTALION Page 3 For ^Sports Day^ Events 800 High School Aggie Five Encounters Seniors Due Here Longhorns At Austin By BARRY HART Assistant Sports Editor With Southern Methodist’s un west Conference Raymond Downs scoring artist, was one of 15 play The names of more than 800 outstanding' high school beaten quintet already occupying poured in 49 points, one shy of ers mentioned on all-SWC cage seniors have been submitted by about 40 home town clubs the Southwest Confei'ence throne the record set by SMU’s Jim teams. Brophy is tied with soph on the campus to be invited to A&M’s annual High School Day room, A&M and Texas meet at Krebs earlier this year. omore Ken Hutto for the individual program this weekend. Austin tonight in a game that could The Aggies haven’t beaten Texas scoring lead on the A&M squad “Sports Day", scheduled to begin Saturday at 1 p.m., is see the Aggies and Longhorns wind in Gregory Gym since 1951, and with 294 points over the season. expected to get most of the attention from the young guests. up the season in a fourth place tie. can boast only two conference wins Brophy and Hutto are tied for Tickets to this full day of* Tonight’s game will be broad over the Horns in their last nine ninth and 10th in SWC season all three schools. sports activities are $1 and cast over KORA starting at 8. meetings. A&M edged by Texas scoring. -

2017 Houston Football Media Guide Uhcougars.Com Houstonfootball Media Information

HOUSTONFOOTBALL HOUSTON FOOTBALL 2017 SEASON 2017 >> 2017 OPPONENTS COACHING STAFF SEPTEMBER 2 SEPTEMBER 9 SEPTEMBER 16 SEPTEMBER 23 AT UTSA AT ARIZONA RICE TEXAS TECH Date: Sept. 2, 2017 Date: Sept. 9, 2017 Date: Sept. 16, 2017 Date: Sept. 23, 2017 Location: San Antonio, Texas Location: Tucson, Ariz. Location: TDECU Stadium Location: TDECU Stadium THE COUGARS Series: Series tied 1-1 Series: Series tied 1-1 Series: Houston leads 29-11 Series: Houston leads 18-11-1 Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Last Meeting: UTSA 27, Houston 7 | 2014 Arizona 37, Houston 3 | 1986 Houston 31, Rice 26 | 2013 Texas Tech 35, Houston 20 | 2010 SEPTEMBER 30 OCTOBER 7 OCTOBER 14 OCTOBER 19 SEASON REVIEW AT TEMPLE SMU AT TULSA MEMPHIS Date: Sept. 30, 2017 Date: Oct. 7, 2017 Date: Oct. 14, 2017 Date: Oct. 19, 2017 Location: Philadelphia, Pa. Location: TDECU Stadium Location: Tulsa, Okla. Location: TDECU Stadium Series: Houston leads 5-0 Series: Houston leads 20-11-1 Series: Houston leads 23-18 Series: Houston leads 15-10 Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Houston 24, Temple 13 | 2015 SMU 38, Houston 16 | 2016 Houston 38, Tulsa 31 | 2016 Memphis 48, Houston 44 | 2016 HISTORY & RECORDS HISTORY TM OCTOBER 28 NOVEMBER 4 NOVEMBER 18 NOVEMBER 24 EAST CAROLINA AT USF AT TULANE NAVY Date: Oct. 28, 2017 Date: Nov. 4, 2017 Date: Nov. 18, 2017 Date: Nov. 24, 2017 Location: TDECU Stadium Location: Tampa, Fla. Location: New Orleans, La. Location: TDECU Stadium Series: East Carolina leads 7-5 Series: Series tied 2-2 Series: Houston leads 16-5 Series: Houston leads 2-1 Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Last Meeting: Last Meeting: East Carolina 48, Houston 28 | 2012 Houston 27, USF 3 | 2014 Houston 30, Tulane 18 | 2016 Navy 46, Houston 40 | 2016 1 @UHCOUGARFB #HTOWNTAKEOVER HOUSTONFOOTBALL MEDIA INFORMATION HOUSTON ATHLETICS COMMUNICATIONS >> 2017 SEASON 2017 DAVID BASSITY JEFF CONRAD ALLISON MCCLAIN ROMAN PETROWSKI KYLE ROGERS ALEX BROWN SENIOR ASSOCIATE AD ASSISTANT AD DIRECTOR ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR ASSISTANT DIRECTOR TED NANCE COMMUNICATIONS ASST. -

The Southeastern Conference, This Is the New Home of Texas A&M

For Texas A&M fans, an introduction to the schools, teams and places of the Southeastern Conference, This is the new home of Texas A&M. Country The Southeastern Conference Members Alabama Crimson Tide Arkansas Razorbacks 752 981 Auburn Tigers Florida Gators 770 936 Georgia Bulldogs 503 Kentucky Wildcats 615 1,035 Louisiana State Tigers 896 Ole Miss Rebels 629 571 756 Mississippi State Bulldogs Missouri Tigers 925 South Carolina Gamecocks 340 Tennessee Volunteers Texas A&M Aggies Vanderbilt Commodores Number below logo indicates mileage from College Station. ATM_0712_SECInsert.indd 1 7/3/12 2:03 PM As Texas A&M prepared for its fi rst year in the SEC, Th e Association of Former Students reached out to Aggies who live and work in SEC cities to learn about each university’s key traditions, landmarks and other local hotspots. University of Alabama www.ua.edu On the banks of the Black by UA fans as a nod to long-time famous homemade biscuits at Warrior River in Alabama sits football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant, Th e Waysider, Tuscaloosa’s oldest a school that once bordered the who was known for wearing a restaurant that was featured on town, but now sits in the center houndstooth hat during games. ESPN’s “Taste of the Town” segment of Tuscaloosa. At Texas A&M, the “Ninety percent of tailgating for in 2008. Th e closest A&M Club mascot is a dog and the Aggies say UA fans takes place on the Quad to Tuscaloosa is the Birmingham “Gig ‘em,” which fi ts right in with (Simpson Drill Field times two); A&M Club, tx.ag/BAMC. -

Football League, Rejected a Ited Future As Reasons

State golf tournaments Page 2 Lining up for Buckner Page3 Wisconsin State Journal Tuesday, July 27,1987, Section 2 • Letters to sports editor Page 4 With Wright out, Jaworski might be in By Tom Oates make some adjustment in their offer cooled when they acquired David becomes quite evident that the posi- to us," Schaeffer said Monday. Woodley from Pittsburgh on June 30 tion we've taken is most reasonable. Sports reporter Schaeffer termed the contract for a lOth-round draft pick. They re- But they're fixed at a point that is not Packer notes, NFL notes on Page 2 proposals "quite far apart," and said newed their interest last Tuesday, acceptable to us." It looks more and more like start- no date has been set for additional however, saying they did so because Schaeffer doesn't think the re- ing quarterback Randy Wright will talks. He said it would take at least it was apparent that Wright would not building Packers will sign Jaworski not be signed by the time the Green one full day of negotiations to reach be in camp on time. for more than they would sign Wright. Bay Packers officially open training an agreement. Jaworski, who has unsuccessfully He cited Jaworski's age — he's 10 camp Wednesday. Wright started every game last shopped his services around the Na- years older than Wright — and lim- It also looks more and more like season and made $185,000 in base sal- tional Football League, rejected a ited future as reasons. long-time Philadelphia Eagle quar- ary.