Genomic Resources and Transcriptome Mining in Agave Tequilana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona Game and Fish Department Heritage Data Management System

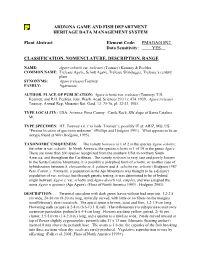

ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT HERITAGE DATA MANAGEMENT SYSTEM Plant Abstract Element Code: PMAGA010N2 Data Sensitivity: YES CLASSIFICATION, NOMENCLATURE, DESCRIPTION, RANGE NAME: Agave schottii var. treleasei (Toumey) Kearney & Peebles COMMON NAME: Trelease Agave, Schott Agave, Trelease Shindagger, Trelease’s century plant SYNONYMS: Agave treleasei Toumey FAMILY: Agavaceae AUTHOR, PLACE OF PUBLICATION: Agave schottii var. treleasei (Toumey) T.H. Kearney, and R.H. Peebles, Jour. Wash. Acad. Sciences 29(11): 474. 1939. Agave treleasei Toumey, Annual Rep. Missouri Bot. Gard. 12: 75-76, pl. 32-33. 1901. TYPE LOCALITY: USA: Arizona: Pima County: Castle Rock, SW slope of Santa Catalina Mt. TYPE SPECIMEN: HT: Toumey s.n. (“in herb. Toumey”); possibly IT at: ARIZ, MO, US. “Present location of specimen unknown” (Phillips and Hodgson 1991). What appears to be an isotype found at MO (Hodgson, 1995). TAXONOMIC UNIQUENESS: The variety treleasei is 1 of 2 in the species Agave schottii; the other is var. schottii. In North America, the species schottii is 1 of 34 in the genus Agave. There are more than 200 species recognized from the southern USA to northern South America, and throughout the Caribbean. The variety treleasei is very rare and poorly known. In the Santa Catalina Mountains, it is possibly a polyploid form of schottii, or another case of hybridization between A. chrysantha or A. palmeri and A. schottii var. schottii (Hodgson 1987 Pers. Comm.). Formerly, a population in the Ajo Mountains was thought to be a disjunct population of var. treleasi, but through genetic testing, it was determined to be of hybrid origin between Agave s. -

Pollination Biology of Two Chiropterophilous Agaves in Arizona1

American Journal of Botany 87(6): 825±836. 2000. POLLINATION BIOLOGY OF TWO CHIROPTEROPHILOUS AGAVES IN ARIZONA1 LIZ A. SLAUSON Desert Botanical Garden, 1201 N. Galvin Parkway, Phoenix, Arizona 85008 USA I studied the pollination biology of two closely related species of agave, Agave palmeri and A. chrysantha (Agavaceae), which exhibit several chiropterophilous (bat-pollinated) traits. Floral studies, ¯oral visitor observations, and pollination studies were conducted over four summers at six different sites to examine ¯oral traits and determine the relative importance of diurnal vs. nocturnal pollinators. Agave chrysantha appears to have developed minor shifts in several ¯oral characters that enhance diurnal pollination. Although ¯oral shifts towards diurnal pollination were fewer in A. palmeri, stigmas were diurnally receptive and copious ¯oral rewards were available in the morning, indicating that some adaptations exist to allow for multiple pollinators. Differences in fruit and seed set between naturally day- and night-pollinated umbels for both species were either not signi®cant or signi®cantly higher in day-pollinated plants. Bats were not important pollinators of A. chry- santha, and the mutualistic relationship between A. palmeri and the lesser long-nosed bat was found to be asymmetric. ``Bat-adapted'' ¯oral traits appear to be ¯exible enough to respond to the climatic and pollinator unpredictability experienced by agaves at the northern edge of their distribution. This variability may be a more important factor affecting evolution of ¯oral characters than a particular pollinator. Key words: Agave chrysantha; Agave palmeri; century plant; fruit set; Leptonycteris curasoae; lesser long-nosed bat; pollination; seed set. Agaves, or century plants, are perennial, rosette-shaped tarivorous, migratory bats from spring as they migrate leaf succulents native to the southwestern United States, north, through the fall when they return to southern roosts Mexico, Central America, and the Canary Islands. -

Exploiting the Potential of Agave for Bioenergy in Marginal Lands Dalal

Exploiting the Potential of Agave for Bioenergy in Marginal Lands Dalal Bader Al Baijan A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biology Newcastle University July 2015 Declaration I hereby certify that this thesis is the result of my own investigations and that no part of it has been submitted for any degree other than Doctor of Philosophy at the Newcastle University. All references to the work of others have been duly acknowledged. Dalal B. Al Baijan ii “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change” Charles Darwin Origin of Species, 1859 iii Abstract Drylands cover approximately 40% of the global land area, with minimum rainfall levels, high temperatures in the summer months, and they are prone to degradation and desertification. Drought is one of the prime abiotic stresses limiting crop production. Agave plants are known to be well adapted to dry, arid conditions, producing comparable amounts of biomass to the most water-use efficient C3 and C4 crops but only require 20% of water for cultivation, making them good candidates for bioenergy production from marginal lands. Agave plants have high sugar contents, along with high biomass yield. More importantly, Agave is an extremely water-use efficient (WUE) plant due to its use of Crassulacean acid metabolism. Most of the research conducted on Agave has centered on A. tequilana due to its economic importance in the tequila production industry. However, there are other species of Agave that display higher biomass yields compared to A. -

Water Relations of Bromeliaceae in Their Evolutionary Context

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2016, 181, 415–440. With 2 figures Think tank: water relations of Bromeliaceae in their evolutionary context JAMIE MALES* Department of Plant Sciences, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EA, UK Received 31 July 2015; revised 28 February 2016; accepted for publication 1 March 2016 Water relations represent a pivotal nexus in plant biology due to the multiplicity of functions affected by water status. Hydraulic properties of plant parts are therefore likely to be relevant to evolutionary trends in many taxa. Bromeliaceae encompass a wealth of morphological, physiological and ecological variations and the geographical and bioclimatic range of the family is also extensive. The diversification of bromeliad lineages is known to be correlated with the origins of a suite of key innovations, many of which relate directly or indirectly to water relations. However, little information is known regarding the role of change in morphoanatomical and hydraulic traits in the evolutionary origins of the classical ecophysiological functional types in Bromeliaceae or how this role relates to the diversification of specific lineages. In this paper, I present a synthesis of the current knowledge on bromeliad water relations and a qualitative model of the evolution of relevant traits in the context of the functional types. I use this model to introduce a manifesto for a new research programme on the integrative biology and evolution of bromeliad water-use strategies. The need for a wide-ranging survey of morphoanatomical and hydraulic traits across Bromeliaceae is stressed, as this would provide extensive insight into structure– function relationships of relevance to the evolutionary history of bromeliads and, more generally, to the evolutionary physiology of flowering plants. -

Plethora of Plants - Collections of the Botanical Garden, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb (2): Glasshouse Succulents

NAT. CROAT. VOL. 27 No 2 407-420* ZAGREB December 31, 2018 professional paper/stručni članak – museum collections/muzejske zbirke DOI 10.20302/NC.2018.27.28 PLETHORA OF PLANTS - COLLECTIONS OF THE BOTANICAL GARDEN, FACULTY OF SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF ZAGREB (2): GLASSHOUSE SUCCULENTS Dubravka Sandev, Darko Mihelj & Sanja Kovačić Botanical Garden, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, Marulićev trg 9a, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia (e-mail: [email protected]) Sandev, D., Mihelj, D. & Kovačić, S.: Plethora of plants – collections of the Botanical Garden, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb (2): Glasshouse succulents. Nat. Croat. Vol. 27, No. 2, 407- 420*, 2018, Zagreb. In this paper, the plant lists of glasshouse succulents grown in the Botanical Garden from 1895 to 2017 are studied. Synonymy, nomenclature and origin of plant material were sorted. The lists of species grown in the last 122 years are constructed in such a way as to show that throughout that period at least 1423 taxa of succulent plants from 254 genera and 17 families inhabited the Garden’s cold glass- house collection. Key words: Zagreb Botanical Garden, Faculty of Science, historic plant collections, succulent col- lection Sandev, D., Mihelj, D. & Kovačić, S.: Obilje bilja – zbirke Botaničkoga vrta Prirodoslovno- matematičkog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu (2): Stakleničke mesnatice. Nat. Croat. Vol. 27, No. 2, 407-420*, 2018, Zagreb. U ovom članku sastavljeni su popisi stakleničkih mesnatica uzgajanih u Botaničkom vrtu zagrebačkog Prirodoslovno-matematičkog fakulteta između 1895. i 2017. Uređena je sinonimka i no- menklatura te istraženo podrijetlo biljnog materijala. Rezultati pokazuju kako je tijekom 122 godine kroz zbirku mesnatica hladnog staklenika prošlo najmanje 1423 svojti iz 254 rodova i 17 porodica. -

Blooming & Dying

BLOOMING & DYING: AGAVE WITHIN TUCSON’S BUILT ENVIRONMENT Item Type text; poster; thesis Authors McGuire, Grace Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture, and the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 11:24:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/632206 1 | Page BLOOMING & DYING AGAVE WITHIN TUCSON’S BUILT ENVIRONMENT: PROPAGATION, PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS, AND DESIGN BY GRACE KATHLEEN MCGUIRE ____________________ A Thesis Submitted to The Honors College In Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelors degree With Honors in Sustainable Built Environments THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA M A Y 2 0 1 9 2 | Page Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Literature Review .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Urban Landscape Theory – Phoenix, AZ as a Nearby Case Study ............................................................ -

EVERYTHING ABOUT PULQUE AGAVOLOGY 'Water from the Green Plants…'

EVERYTHING ABOUT PULQUE AGAVOLOGY 'Water from the green plants…' Tequila's predecessor, pulque, or octli, was made from as many as six types of agave grown in the Mexican highlands. Pulque is one of about thirty different alcoholic beverages made from agave in Mexico - many of which are still made regionally, although seldom available commercially. The drink has remained essential to diet in the central highlands of Mexico since pre-Aztec times. Pulque is like beer - it has a low alcoTeqhol content, about 4-8%, but also contains vegetable proteins, carbohydrates and vitamins, so it also acts as a nutritional supplement in many communities. Unlike tequila or mezcal, the agave sap is not cooked prior to fermentation for pulque. Pulque, is an alcoholic spirit obtained by the fermentation of the sweetened sap of several species of 'pulqueros magueyes' (pulque agaves), also known as Maguey Agaves. It is a traditional native beverage of Mesoamerica. Though it is commonly believed to be a beer, the main carbohydrate is a complex form of fructose rather than starch. The word 'pulque' comes from the Náhuatl Indian root word poliuhqui, meaning 'disturbed'. There are about twenty species of agave and several varieties of pulque. Of these there was one that was called "metlaloctli" ie "blue pulque," for its colouration. Plant Sources of Pulque The maguey plant is not a cactus (as has sometimes been mistakenly suggested) but an Agave, believed to be the Giant Agave (Agave salmiana subspecies salmiana). The plant was one of the most sacred plants in Mexico and had a prominent place in mythology, religious rituals, and Mesoamerican industry. -

Manual for the in Vitro Culture of Agaves. Common Fund For

OCCASION This publication has been made available to the public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. DISCLAIMER This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. FAIR USE POLICY Any part of this publication may be quoted and referenced for educational and research purposes without additional permission from UNIDO. However, those who make use of quoting and referencing this publication are requested to follow the Fair Use Policy of giving due credit to UNIDO. CONTACT Please contact [email protected] for further information concerning UNIDO publications. For more information about UNIDO, please visit us at www.unido.org UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26026-0 · www.unido.org · [email protected] UNITED NATIONS COMMON FUND INDUSTRIAL FOR COMMODITIES DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION - --' Com man Fund for Com mod ities Technical Paper no. -

Journal of Natural History

This article was downloaded by:[Sánchez, Ragde] On: 30 August 2007 Access Details: [subscription number 781714108] Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Natural History Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713192031 Food habits of the threatened bat Leptonycteris nivalis (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) in a mating roost in Mexico Online Publication Date: 01 January 2007 To cite this Article: Sánchez, Ragde and Medellín, Rodrigo A. (2007) 'Food habits of the threatened bat Leptonycteris nivalis (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) in a mating roost in Mexico', Journal of Natural History, 41:25, 1753 - 1764 To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/00222930701483398 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222930701483398 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Brad.N39.2021.A23

Additional species of Agave (Agavoideae/Agavaceae, Asparagaceae sensu lat.) introduced and naturalising in Tunisia and North Africa Authors: Mokni, Ridha El, and Verloove, Filip Source: Bradleya, 2021(39) : 221-235 Published By: British Cactus and Succulent Society URL: https://doi.org/10.25223/brad.n39.2021.a23 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non - commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/Bradleya on 18 Jun 2021 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by Botanic Garden Meise Bradleya 39/2021 pages 221–235 Additional species of Agave (Agavoideae /Agavaceae, Asparagaceae sensu lat.) introduced and naturalising in Tunisia and North Africa Ridha El Mokni1,2,3 and Filip Verloove4 1. University of Monastir, Laboratory of Botany, Cryptogamy and Plant Biology, Faculty of Pharmacy of Monastir, Avenue Avicenna, 5000-Monastir, Tunisia. (email: [email protected]) 2.University of Jendouba, Laboratory of Silvo-Pastoral Resources, Silvo-Pastoral Institute of Tabarka, B P. -

A Synopsis of Feral Agave and Furcraea (Agavaceae, Asparagaceae S. Lat.) in the Canary Islands (Spain)

Plant Ecology and Evolution 152 (3): 470–498, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5091/plecevo.2019.1634 REGULAR PAPER A synopsis of feral Agave and Furcraea (Agavaceae, Asparagaceae s. lat.) in the Canary Islands (Spain) Filip Verloove1,*, Joachim Thiede2, Águedo Marrero Rodríguez3, Marcos Salas-Pascual4, Jorge Alfredo Reyes-Betancort5, Elizabeth Ojeda-Land6 & Gideon F. Smith7 1Meise Botanic Garden, Nieuwelaan 38, B-1860 Meise, Belgium 2Schenefelder Holt 3, 22589 Hamburg, Germany 3Jardín Botánico Canario Viera y Clavijo, Unidad Asociada al CSIC, C/ El Palmeral nº 15, Tafira Baja, E-35017 Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain 4Instituto de Estudios Ambientales y Recursos Naturales (i-UNAT), Campus Universitario de Tafira, Universidad de las Palmas de Gran Canaria, E-35017 Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain 5Jardín de Aclimatación de La Orotava (ICIA). C/ Retama 2, 38400 Puerto de la Cruz, Canary Islands, Spain 6Viceconsejería de Medio Ambiente. Gobierno de Canarias. C/ Avda. de Anaga, 35. Planta 11. 38071 Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain 7Department of Botany, P.O. Box 77000, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, 6031 South Africa / Centre for Functional Ecology, Departamento de Ciências da Vida, Calçada Martim de Freitas, Universidade de Coimbra, 3001-455 Coimbra, Portugal *Corresponding author: [email protected] Background – Species of Agave and Furcraea (Agavaceae, Asparagaceae s. lat.) are widely cultivated as ornamentals in Mediterranean climates. An increasing number is escaping and naturalising, also in natural habitats in the Canary Islands (Spain). However, a detailed treatment of variously naturalised and invasive species found in the wild in the Canary Islands is not available and, as a result, species identification is often problematic. -

The Genus Agave in Agroforestry Systems of Mexico El Género Agave En Los Sistemas Agroforestales De México

Botanical Sciences 97 (3): 263-290. 2019 Received: February 1, 2019, accepted: May 29, 2019 DOI: 10.17129/botsci.2202 On line first: 25/08/2019 Review/Revisión The genus Agave in agroforestry systems of Mexico El género Agave en los sistemas agroforestales de México Ignacio Torres-García1, Francisco Javier Rendón-Sandoval2, José Blancas3, Alejandro Casas2, and Ana Isabel Moreno-Calles1,* 1 Laboratorio de Estudios Transdisciplinarios Ambientales. Escuela Nacional de Estudios Superiores Unidad Morelia (ENES Morelia). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Michoacán, México. 2 Laboratorio de Manejo y Evolución de Recursos Genéticos, Instituto de Investigaciones en ecosistemas y Sustentabilidad (IIES). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Michoacán, México. 3 Centro de Investigaciones en Biodiversidad y Conservación. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, México. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Background: The genus Agave L. is recognized for its wide distribution in Mexican ecosystems. Species have been described as multipurpose as part of agroforestry systems (AFS). There has not been a systematized, detailed analysis about its richness in AFS nor their ecological, economic and cultural relevance. Questions: What is the Agave richness in Mexican AFS? What is their ecological, agronomical, economic and cultural relevance? What are the risks and perspectives for strengthening their role in AFS? Species studied: 31 Agave species in Mexican AFS. Study site and dates: AFS throughout Mexican territory. January to august 2018. Methods: Systematization of published information, scientific reports, repositories, and our fieldwork, was performed. The data base “The genus Agave in AFS of Mexico” was created, containing information about Agave richness in AFS, ecological, economic and cultural relevance, as well as the current and future perspectives of the AFS they are included in.