University of Warwick Institutional Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

Set Checklist I Have the Complete Set 1972/73 Arbeshi Reproductions George Keeling Caricatures

Nigel's Webspace - English Football Cards 1965/66 to 1979/80 Set checklist I have the complete set 1972/73 Arbeshi Reproductions George Keeling caricatures Peter Allen Orient Brian Hall Liverpool Terry Anderson Norwich City Paul Harris Orient Robert Arber Orient Ron Harris Chelsea George Armstrong Arsenal David Harvey Leeds United Alan Ball Arsenal Steve Heighway Liverpool Gordon Banks - All Stars Stoke City Ricky Heppolette Orient Geoff Barnett Arsenal Phil Hoadley Orient Phil Beal Tottenham Hotspur Pat Holland West Ham United Colin Bell - All Stars Manchester City John Hollins Chelsea Peter Bennett Orient Peter Houseman Chelsea Clyde Best West Ham United Alan Hudson Chelsea George Best - All Stars Manchester United Emlyn Hughes - All Stars Liverpool Jeff Blockley - All Stars Arsenal Emlyn Hughes Liverpool Billy Bonds West Ham United Norman Hunter Leeds United Jim Bone Norwich City Pat Jennings Tottenham Hotspur Peter Bonetti Chelsea Mick Jones Leeds United Ian Bowyer Orient Kevin Keegan Liverpool Billy Bremner Leeds United Kevin Keegan - All Stars Liverpool Max Briggs Norwich City Kevin Keelan Norwich City Terry Brisley Orient Howard Kendall - All Stars Everton Trevor Brooking West Ham United Ray Kennedy Arsenal Geoff Butler Norwich City Joe Kinnear Tottenham Hotspur Ian Callaghan Liverpool Cyril Knowles Tottenham Hotspur Clive Charles West Ham United Frank Lampard West Ham United Jack Charlton Leeds United Chris Lawler Liverpool Martin Chivers Tottenham Hotspur Alec Lindsay Liverpool Allan Clarke Leeds United Doug Livermore Norwich -

FA Cup Quiz Answers

QUIZ TIME FA Cup Quiz - Answers 1. Charlton Athletic played in the first two finals after the war, in 1946 and 1947. On both occasions an event occurred which was unique in cup final history at that time. What was it? The ball burst in both matches 2. Which team was the first to win the FA cup at the Cardiff Millennium stadium? Liverpool 3. In 1970, the FA cup final between Chelsea and Leeds United went to a replay for the first time in 58 years! The first game was at Wembley, but which stadium hosted the replay? Old Trafford 4. In what year was the first ever FA cup final held? 1872 5. Which club lost successive finals in the 1980s? Everton 6. Who were the winners of the 1980 FA cup final and which England international scored the only goal? West Ham United, Trevor Brooking 7. Which of these famous players never played in an FA cup final in his career? Peter Shilton, Kevin Keegan, Bobby Charlton or George Best? George Best 8. The song ‘Ossie’s dream’ was recorded to commemorate Tottenham Hotspur reaching the FA cup final in which year? 1981 9. Only one non-English team has ever won the FA cup, who was it? Cardiff City 10. Which team produced one of the biggest shocks in the history of the competition to win the 1988 FA cup final? Wimbledon 11. The 1953 FA cup final also known as the ‘Matthews final’ saw which team win by a score of 4 goals to 3? Blackpool 12. -

GK1 - FINAL (4).Indd 1 22/04/2010 20:16:02

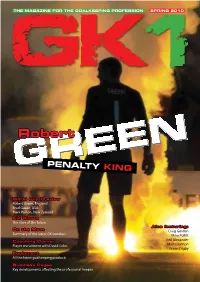

THE MAGAZINE FOR THE GOALKEEPING PROFESSION SPRING 2010 Robert PENALTY KING World Cup Preview Robert Green, England Brad Guzan, USA Mark Paston, New Zealand Kid Gloves The stars of the future Also featuring: On the Move Craig Gordon Summary of the latest GK transfers Mike Pollitt Coaching Corner Neil Alexander Player recruitment with David Coles Matt Glennon Fraser Digby Equipment All the latest goalkeeping products Business Pages Key developments affecting the professional ‘keeper GK1 - FINAL (4).indd 1 22/04/2010 20:16:02 BPI_Ad_FullPageA4_v2 6/2/10 16:26 Page 1 Welcome to The magazine exclusively for the professional goalkeeping community. goalkeeper, with coaching features, With the greatest footballing show on Editor’s note equipment updates, legal and financial earth a matter of months away we speak issues affecting the professional player, a to Brad Guzan and Robert Green about the Andy Evans / Editor-in-Chief of GK1 and Director of World In Motion ltd summary of the key transfers and features potentially decisive art of saving penalties, stand out covering the uniqueness of the goalkeeper and hear the remarkable story of how one to a football team. We focus not only on the penalty save, by former Bradford City stopper from the crowd stars of today such as Robert Green and Mark Paston, secured the All Whites of New Craig Gordon, but look to the emerging Zealand a historic place in South Africa. talent (see ‘kid gloves’), the lower leagues is a magazine for the goalkeeping and equally to life once the gloves are hung profession. We actively encourage your up (featuring Fraser Digby). -

Sample Download

DANNY LEWIS BOLEYNTHE ’S THE BOLEYN FAREWELL WEST HAM UNITED’S UPTON PARK SWANSONG ' S FAREWELL Contents Foreword by Tony Cottee 7 Introduction 10 1. The Backdrop 15 2. Preparation 33 3. Before The Game 39 4. First Half 89 5. Half-Time 127 6. Second Half 131 7. The Ceremony 204 8. It’s All Over 235 9. The Aftermath 261 Acknowledgements 281 Bibliography 284 1 The Backdrop INCLUDING THE club’s time as Thames Ironworks, the Hammers had already played at three stadia before moving in at the Boleyn Ground: Hermit Road, Browning Road and Memorial Grounds. The move to Upton Park came about when, in 1904, Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company owner Arnold Hills was having financial issues. Hills was unwilling to re-negotiate a deal for the club to remain at Memorial Grounds, meaning the Hammers needed to find a new place to call home. Upton Park was settled upon, where the club would play its football from the 1904/05 season right up until 2016. The stadium, which was originally named The Castle, was built next to and in the grounds of Green Street House. The pitch was laid on an area that had previously been used to grow cabbages and potatoes. The stadium originally consisted of a small West Stand, a covered terrace backing on to Priory Road and changing rooms placed in the north- west corner between the West Stand and North Bank. West Ham’s first game at Upton Park came on Thursday, 1 September 1904, when they beat long-standing rivals 15 THE BOLEYN’S Farewell Millwall 3-0 in front of 10,000 fans. -

Football Photos FPM01

April 2015 Issue 1 Football Photos FPM01 FPG028 £30 GEORGE GRAHAM 10X8" ARSENAL FPK018 £35 HOWARD KENDALL 6½x8½” EVERTON FPH034 £35 EMLYN HUGHES 6½x8½" LIVERPOOL FPH033 £25 FPA019 £25 GERARD HOULLIER 8x12" LIVERPOOL RON ATKINSON 12X8" MAN UTD FPF021 £60 FPC043 £60 ALEX FERGUSON BRIAN CLOUGH 8X12" MAN UTD SIGNED 6½ x 8½” Why not sign up to our regular Sports themed emails? www.buckinghamcovers.com/family Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF FPM01 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] Manchester United FPB002 £50 DAVID BECKHAM FPB036 NICKY BUTT 6X8” .....................................£15 8X12” MAGAZINE FPD019 ALEX DAWSON 10X8” ...............................£15 POSTER FPF009 RIO FERDINAND 5X7” MOUNTED ...............£20 FPG017A £20 HARRY GREGG 8X11” MAGAZINE PAGE FPC032 £25 JACK CROMPTON 12X8 FPF020 £25 ALEX FERGUSON & FPS003 £20 PETER SCHMEICHEL ALEX STEPNEY 8X10” 8X12” FPT012A £15 FPM003 £15 MICKY THOMAS LOU MACARI 8X10” MAN UTD 8X10” OR 8X12” FPJ001 JOEY JONES (LIVERPOOL) & JIMMY GREENHOFF (MAN UNITED) 8X12” .....£20 FPM002 GORDON MCQUEEN 10X8” MAN UTD ..£20 FPD009 £25 FPO005 JOHN O’SHEA 8X10” MAGAZINE PAGE ...£5 TOMMY DOCHERTY FPV007A RUUD VAN NISTELROOY 8X12” 8X10” MAN UNITED PSV EINDHOVEN ..............................£25 West Ham FPB038A TREVOR BROOKING 12X8 WEST HAM . £20 FPM042A ALVIN MARTIN 8X10” WEST HAM ...... £10 FPC033 ALAN CURBISHLEY 8X10 WEST HAM ... £10 FPN014A MARK NOBLE 8X12” WEST HAM ......... £15 FPD003 JULIAN DICKS 8X10” WEST HAM ........ £15 FPP006 GEOFF PIKE 8X10” WEST HAM ........... £10 FPD012 GUY DEMEL 8X12” WEST HAM UTD..... £15 FPP009 GEORGE PARRIS 8X10” WEST HAM .. £7.50 FPD015 MOHAMMED DIAME 8X12” WEST HAM £10 FPP012 PHIL PARKES 8X10” WEST HAM ........ -

World Cup Pack

The BBC team Who’s who on the BBC team Television Presentation Team – BBC Sport: Biographies Gary Lineker: Presenter is the only person to have won all of the honours available at club level at least twice and captained the Liverpool side to a historic double in 1986. He also played for Scotland in the 1982 World Cup. A keen tactical understanding of the game has made him a firm favourite with England’s second leading all-time goal-scorer Match Of The Day viewers. behind Sir Bobby Charlton, Gary was one of the most accomplished and popular players of his Mark Lawrenson: Analyst generation. He began his broadcasting career with BBC Radio 5 in Gary Lineker’s Football Night in 1992, and took over as the host of Sunday Sport on the re-launched Radio Five Live in 1995. His earliest stint as a TV pundit with the BBC was during the 1986 World Cup finals following England’s elimination by Argentina. Gary also joined BBC Sport’s TV team in 1995, appearing on Sportsnight, Football Focus and Match Of The Day, and became the regular presenter of Football Focus for the new season. Now Match Of The Day’s anchor, Gary presented highlights programmes during Euro 96, and hosted both live and highlights coverage of the 1998 World Cup finals in France. He is also a team captain on BBC One’s hugely successful sports quiz They Think It’s All Over. Former Liverpool and Republic of Ireland defender Mark Lawrenson joined BBC Alan Hansen: Analyst Television’s football team as a pundit on Match Until a knee injury ended his playing career in Of The Day in June 1997. -

PAT WELTON INTERVIEW ^EJ Fk^F Top Nostalgia" Buffs" "Arthur Godfrey and Dave Knight Take a Wander Down Memory Lane and Have a Few Pints With' Pat Welton

"N%? . Wl &• 's': PAT WELTON INTERVIEW ^EJ fK^f Top nostalgia" buffs" "Arthur Godfrey and Dave Knight take a wander down memory lane and have a few pints with' Pat Welton. Pat Welton joined the club as a goal- As Pat had a lot of family and frien- keeper in 1947. He had just come out ds up there, Alex Stock gave him spe- of the army and wasn't sure of what cial permisssion to stay behind and to do. His brother had been in the come back on the train. Pat didn t army with Arthur Banner (O's skipper think, there would be many 0's fans I at the time) and they arranged a tri- at Euston. But he couldn t have been al for Pat. He had his trial on a more wrong, and as soon as the fans I Tuesday and he played for the 0's on saw him he was carried shoulder high the Saturday. in triumph. Things may have worked out differ- ent because'1 during his army time Pat played basketball as well as football. • He had considered trying for a place in the British Olympic team, but opt- ed for football. Eventually he was signed as a pro- fessional so his wages were £7.00 during the season and £5.00 in the summer. He made his debut at Notts County in October 1949, where he cou- Idn't have had a more dramatic intro- duction to league football, the Magp- ies winning 7-1. The first thing he learnt was how to pick the ball out of the net. -

The Soldiers' Game

THE MAGAZINE SOLDIERS’ OF THE ARMY FA GAME Issue 11 - Winter Edition 2013 IN THIS ISSUE LEGENDS OUT IN FORCE TO COMMEMMORATE ARMY MILESTONE England LEGEND Coaches Army Team FOR ANNIVersary Day REME SPORTSPERSON OF THE YEAR 2013 Benefits Every Army Sports Lottery (ASL) ticket is entered into a weekly prize draw with the opportunity of winning weekly cash prizes of £25,000 (25k). Approximately £1.35 million is distributed in Prize Money each year. In addition, members can benefit through: Overseas Sports Tours Funding, Sports Official/Coaching Courses, International Competitors Grants, Olympic, World & Commonwealth Games, Competitors Grants and Winter Sports Competition Funding. How can I join? Membership is open to all members of the Regular Army and their equivalents, e.g. FTRS, MPGS, are eligible to join. Payment is deducted at source by JPA. All members of the TA and their equivalents are eligible to join. Payment is made in advance by annual cheque made payable to ‘Army Sports Lottery’. The minimum period of membership is 12 months. Military Support Force (MSF)/Retired Officer (RO)/Retired Other Rank (OR). MSF/RO/OR who are ex-Army, are employed by the MOD and have a military address are eligible to join. Payment is as for the TA. To apply, complete and return JS Form JPA EO15, available through your local Gymnasium, Unit Admin Office or our website. How do I apply for a grant? Application forms for Army Sports Lottery Grants can be found at: www.armysportslottery.com • www.armynet.mod.uk email: [email protected] • DII: ASCB-ASL-LM -

Team Checklist I Have the Complete Set 1972/73 A&BC Chewing Gum (English) Footballer, Orange/Red Backs, Series 1 (1 to 109)

Nigel's Webspace - English Football Cards 1965/66 to 1979/80 Team checklist I have the complete set 1972/73 A&BC chewing gum (English) Footballer, Orange/Red backs, Series 1 (1 to 109) 108 Bryan Hamilton 084 Robert (Sammy) Chapman 042 Derek Jefferson 040 Peter Cormack 045 Checklist 1 064 Mick Mills 018 Peter Hindley Arsenal 086 Jimmy Robertson 062 Barry Lyons 101 George Armstrong Leeds United Sheffield United 079 Charlie George 039 Billy Bremner 044 Len Badger 035 George Graham 023 Jack Charlton 022 Tony Currie 013 Peter Marinello 083 Terry Cooper 099 Edward (Ted) Hemsley 057 Bob Wilson 105 John Giles 088 Geoff Salmons Chelsea 061 Mick Jones 066 Stewart Scullion 015 Tommy Baldwin 017 Gareth (Gary) Sprake Southampton 103 Charlie Cooke Leicester City 091 Ron Davies 059 Ron Harris 014 Graham Cross 047 Jimmy Gabriel 081 Pat (Paddy) Mulligan 058 David Nish 003 Eric Martin 037 Peter Osgood 102 Jon Sammels 069 Terry Paine Coventry City 080 Peter Shilton 025 Bobby Stokes 056 Jeff Blockley 036 Steve Whitworth Stoke City 078 Chris Cattlin Liverpool 055 Gordon Banks 100 Mick Coop 052 Ian Callaghan 090 Alan Bloor 034 Ernie Machin 030 Ray Clemence 011 John Mahoney 012 Quinton Young 001 Brian Hall 077 Mike Pejic Crystal Palace 008 Alec Lindsay 033 Denis Smith 085 Mel Blyth 074 Larry Lloyd Tottenham Hotspur 041 John Jackson 096 John Toshack 050 Phil Beal 063 David Payne Manchester City 094 Martin Chivers 107 Bobby Tambling 075 Tony Book 028 Ralph Coates 019 Peter Wall 097 Joe Corrigan 072 Peter Collins Derby County 031 Wyn Davies 006 Steve Perryman -

Can I Kick It? Unit 4 How Money Took Over1 Football…

Unit 4 Can I Kick It? How Money Took over1 Football… in 1879 No turnstiles2, no tickets, no huge wage demands. Late 19th-century football was a serene place… until money came along and turned it into the monster we love and loathe3 today. The first recorded outbreak of ‘professionalism’ occurred in Lancashire when Darwen employed two Scots, Fergie Suter and James Love, in 1879. Though it caused a minor scandal, players had been secretly paid – in cash, fish, beer, whatever – for years. In 1885, professionalism was legalised and in 1901 a £4-a-week wage limit introduced. The Football Association (FA) tried to cling4 to amateur ideals, but in 1905 Middlesbrough broke the bank5, buying Sunderland’s Alf Common for a record £1,000. Boro had been languishing6 near the relegation places in Division One, but with Common on board, they leapt7 up to mid-table anonymity and languished there for a bit. By 1922 the maximum wage had grown to £8 a week (£6 in the summer), and clubs also gave a loyalty bonus of £650 after five years. The money no longer came from the club owners either – since Small Heath (Birmingham City) set the trend in 1888, clubs had been turning themselves into limited companies and directors saw football as a money-spinning8 pension plan. The first £10,000 transfer came in 1928 when Arsenal bought David Jack from Bolton (none of the money going to the player or his agent), but by the time Jimmy Guthrie took over as chairman of the Players’ Union in 1947, the maximum wage was still only £12 a week (£10 in the summer). -

Brief for the Position of Executive Assistant, National Football Museum June 2018

Brief for the position of Executive Assistant, National Football Museum June 2018 BACKGROUND The National Football Museum explains how and why football has become ‘the people’s game’, a key part of England’s heritage and way of life. It also aims to explain why England is the home of football, the birthplace of the world’s most popular sport. The Museum originally opened in Preston in 2001. Home to a collection of over 140,000 boots, balls, programmes, paintings, postcards and ceramics (including the prestigious FIFA collection), it was situated at Preston North End’s Deepdale ground. While the museum was a critical success and popular with visitors, external funding was withdrawn and the doors closed to the public in 2010. Manchester City Council agreed to fund a new National Football Museum to be situated in the Urbis building, designed by Manchester architect Ian Simpson. After investment from the European Regional Development Fund, the National Football Museum opened in Manchester in July 2012. Over the first six weeks of opening the museum welcomed in excess of 100,000 visitors and in just over two years over 1 million had walked through the turnstiles. Visitors from across the globe continue to enjoy world class objects (over 2,500 are on display at any one time), ground-breaking interactives and a changing programme of temporary exhibitions, linking football to topics as diverse as fashion, history, art and World War 1. The museum’s president is Sir Bobby Charlton. Vice Presidents include Sir Alex Ferguson, Sir Trevor Brooking and Sir Geoff Hurst.