Itchen Ferry Village Education Pack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southampton Tall Buildings Study 6

SENSITIVITY OF KEY HERITAGE ASSETS TO TALL BUILDINGS STMIC.1 Itchen Bridge to St Michael’s Church N Figure.20 STMIC.1 Summary of view View, viewing area Itchen Bridge is a clearly defined, busy and exposed place and assessment point from which to experience a wide panorama of the city centre. The foreground is dominated by the bridge and low rise undistinguished commercial, industrial, large service yards and K residential buildings. The tree line of Central Park provides a break in built form to the northern extent of the view. The wide background of the panorama includes a number of clusters of tall buildings and focal points. Moresby Tower at Ocean Village dominates the skyline. There is little order or prevailing character amongst the groups of large commercial and residential slabs and stepped towers around Ocean Village, Extent of View from Terminus Terrace or Charlotte Place. The view takes in the spire Assessment Point of St Michael’s Church, the spire of St Mary’s Church, the Civic Centre Campanile, the tree canopy of Central Parks and listed Heritage Asset Viewing buildings within the Canute Road Conservation Area. Cranes and Area docked cruise ships (to Western Docks) can be glimpsed on the skyline. Assessment Point The central tower and slender needle-like steeple of St Michael’s Grade I Listed Buildings and/or Church can be clearly made out on the skyline. The tall Scheduled Ancient Monument building cluster at Terminus Terrace however, which consists of Grade II and II* Listed Richmond House, Mercury Point and Duke’s Keep dominate and STMIC.1 Buildings out compete with the church in the central part of the view. -

1992 Southampton Wildlife Link Peartree Green

,~ ,,-_ /,,- 1 1 ' /.....,;l A NATURAL HISTORY \....,;' OF PEARTREE GREEN I ' I I ..._._ - .. - A REPORT BY SOUTHAMPTON WILDLIFE LINK •b... -. _' ....... ._J Broadlands Valley Conservation Group, Hampshire Badger Link, Hampshire & lOW I 1 ." Naturalist's Trust, Southampton Commons and Parks Protection Society, .. - Southampton Natural History Society, Southampton Schools Conservation Corps, Hawthorns Wildlife Association, British Butterfly Conservation Society, R.S.P.B. ..._ British Trust for 'Ornithology, English Nature . Hon. Sec. Mrs P. Loxton, 3 Canton St, Southampton J February 1992 - /~ c !-> r=f. ~- ; j L - I 1 I....,. -. I ~ l -~ 1- 1-' L,' - j - Q L c_, 1 Field Rose 5 • 2 Soapwort L s: 3 Hedge B'r o wn . Butterfly . ~4 4 White Mullein L ~ . A3 5 Small Heath Butterfly ~ 6 Field Scabious i .. 7 Musk Mallow '-- ' ~J('.~ ~ . 8 Common Mallow 9 Field Grasshopper ( ,, . 10 Restharrow .._ ~ f:\f)~~lftBfiB ;.,r~._6 11 Kidney Vetch J - ... ;;1~11 ~ 9 j , ~ II 'IlI_ ~UI II. ~.r-'L-I ~~,,~,J J' L --- -- • -.. -I ,~ .,_;'\ , -" ~ -. , . .' o - _J --.. I r-« / -.... Pear tree I G..~_Green ......., I ~ j--'" ,.-... ,. --. I /-.. - - j J ~.,7~~ /- I -I SOUTHAMPTON WILDLIFE LINK I THE" NATURAL HISTORY OF PEARTREE GREEN 1....1 .. , A REPORT I I INTRODUCTION - Peartree Green is a remnant of the Ridgeway Heath that today consists of two parts; the original "village green" (express-ly excluded from. the L enolosure of common land c 1814) and the land below it that is bounded by the railway and Sea Roatl. The Old Common has long been valued as a recreational I L amenity. It was safeguarded from encroachment in 1872 by a Court of Chancery Award, and was duly registered under the 1965 Commons Registration Act as a Town Green. -

Congregationalism in Edwardian Hampshire 1901-1914

FAITH AND GOOD WORKS: CONGREGATIONALISM IN EDWARDIAN HAMPSHIRE 1901-1914 by ROGER MARTIN OTTEWILL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Congregationalists were a major presence in the ecclesiastical landscape of Edwardian Hampshire. With a number of churches in the major urban centres of Southampton, Portsmouth and Bournemouth, and places of worship in most market towns and many villages they were much in evidence and their activities received extensive coverage in the local press. Their leaders, both clerical and lay, were often prominent figures in the local community as they sought to give expression to their Evangelical convictions tempered with a strong social conscience. From what they had to say about Congregational leadership, identity, doctrine and relations with the wider world and indeed their relative silence on the issue of gender relations, something of the essence of Edwardian Congregationalism emerges. In their discourses various tensions were to the fore, including those between faith and good works; the spiritual and secular impulses at the heart of the institutional principle; and the conflicting priorities of churches and society at large. -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Sincs Hampshire.Pdf

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) within Hampshire © Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre No part of this documentHBIC may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recoding or otherwise without the prior permission of the Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre Central Grid SINC Ref District SINC Name Ref. SINC Criteria Area (ha) BD0001 Basingstoke & Deane Straits Copse, St. Mary Bourne SU38905040 1A 2.14 BD0002 Basingstoke & Deane Lee's Wood SU39005080 1A 1.99 BD0003 Basingstoke & Deane Great Wallop Hill Copse SU39005200 1A/1B 21.07 BD0004 Basingstoke & Deane Hackwood Copse SU39504950 1A 11.74 BD0005 Basingstoke & Deane Stokehill Farm Down SU39605130 2A 4.02 BD0006 Basingstoke & Deane Juniper Rough SU39605289 2D 1.16 BD0007 Basingstoke & Deane Leafy Grove Copse SU39685080 1A 1.83 BD0008 Basingstoke & Deane Trinley Wood SU39804900 1A 6.58 BD0009 Basingstoke & Deane East Woodhay Down SU39806040 2A 29.57 BD0010 Basingstoke & Deane Ten Acre Brow (East) SU39965580 1A 0.55 BD0011 Basingstoke & Deane Berries Copse SU40106240 1A 2.93 BD0012 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood North SU40305590 1A 3.63 BD0013 Basingstoke & Deane The Oaks Grassland SU40405920 2A 1.12 BD0014 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood South SU40505520 1B 1.87 BD0015 Basingstoke & Deane West Of Codley Copse SU40505680 2D/6A 0.68 BD0016 Basingstoke & Deane Hitchen Copse SU40505850 1A 13.91 BD0017 Basingstoke & Deane Pilot Hill: Field To The South-East SU40505900 2A/6A 4.62 -

The Waterside Destination at Centenary Quay

AT CENTENARY QUAY THE WATERSIDE DESTINATION SOUTHAMPTON | SO19 Digital illustration of The Azera Apartments CENTENARY QUAY IS FOR LIVING, WORKING AND ENJOYING LIFE, WHILE FEELING CONNECTED AND A PART OF THIS HISTORIC CITY THE ULTIMATE WATERSIDE DESTINATION Centenary Quay is a vibrant waterside community, situated in the cosmopolitan city of Southampton. Offering breathtaking, elevated views of the River Itchen and within easy reach of bars, shops and restaurants, this modern collection of new homes makes everyday life much more exciting. Spend your weekends dining al fresco with friends and in the week, enjoy a hassle-free commute with the excellent transport connections. At Centenary Quay, everything you need is within easy reach. Photography of Centenary Quay WHERE COMFORT MEETS STYLE This new collection of 1 & 2 bedroom apartments is positioned within the heart of an already thriving community. Boasting sleek, contemporary interiors, each home has been designed with modern lifestyles in mind. From first time buyers to downsizers and investors, there’s something here for everyone. Careful thought and consideration has been put into every detail, from the stunning views to the high specification fixtures and fittings. With pathways providing a new route leading to the river, there’s ample opportunity to appreciate your surroundings. Inside, the interiors benefit from a neutral decor, so you can get creative and add your own style as soon as you walk through the door. Photography of Centenary Quay Digital illustration of Centenary Quay WHERE EVERYTHING IS IN ONE PLACE The vibrant community at Centenary Quay is evolving so that you will have everything you need on your doorstep. -

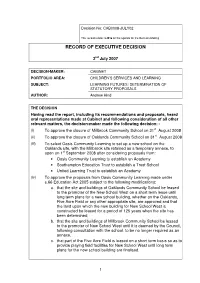

Record of Executive Decision

Decision No: CAB0008-JULY02 This record relates to B1a on the agenda for the Decision-Making RECORD OF EXECUTIVE DECISION 2nd July 2007 DECISION-MAKER: CABINET PORTFOLIO AREA: CHILDREN’S SERVICES AND LEARNING SUBJECT: LEARNING FUTURES: DETERMINATION OF STATUTORY PROPOSALS AUTHOR: Andrew Hind THE DECISION Having read the report, including its recommendations and proposals, heard oral representations made at Cabinet and following consideration of all other relevant matters, the decision-maker made the following decision: - (i) To approve the closure of Millbrook Community School on 31st August 2008 (ii) To approve the closure of Oaklands Community School on 31st August 2008 (iii) To select Oasis Community Learning to set up a new school on the Oaklands site, with the Millbrook site retained as a temporary annexe, to open on 1st September 2008 after considering proposals from: • Oasis Community Learning to establish an Academy • Southampton Education Trust to establish a Trust School • United Learning Trust to establish an Academy (iv) To approve the proposals from Oasis Community Learning made under s.66 Education Act 2005 subject to the following modifications: a. that the site and buildings of Oaklands Community School be leased to the promoter of the New School West on a short term lease until long term plans for a new school building, whether on the Oaklands, Five Acre Field or any other appropriate site, are approved and that the land upon which the new building for New School West is constructed be leased for a period of 125 years when the site has been determined; b. that the site and buildings of Millbrook Community School be leased to the promoter of New School West until it is deemed by the Council, following consultation with the school, to be no longer required as an annexe. -

Submerged Gravel and Peat in Southampton Water

PAPERS AND . PROCEEDINGS 263 SUBMERGED GRAVEL AND PEAT IN SOUTHAMPTON WATER. B y C . E . EVERARD, M.SC. Summary. OCK excavations and numerous bore-holes have shown that gravel and peat-beds, buried by alluvial mud, occur at D many points in Southampton Water and its tributary estuaries. A study of a large number of hitherto unpublished borings has shown that the gravel occurs as terraces, similar to those found above sea-level. There is evidence that the terraces mark stages, three in number, in the excavation of the estuaries during the Pleistocene Period, and that the peat and mud have been deposited mainly during the post-glacial rise in sea-level. Introduction. The Hampshire coast, between Hurst Castle and Hayling Island, illustrates admirably the characteristic estuarine features of a coast of submergence. It is probable that, following the post- glacial rise in sea-level, much of the Channel coast presented a similar appearance, but only in limited areas have the estuaries survived subsequent coastal erosion. The Isle of Wight has, for example, preserved from destruction the Solent and Southampton Water, and their tributary estuaries. The fluviatile origin of these estuaries has been accepted for many years, following the work of Reid (1, 2) and Shore (3, 4), among others, but, as much of the evidence is below low water- level, detailed knowledge of their stratigraphy and history is limited. The deposits of gravel, peat and mud which largely fill the estuaries are known chiefly from dock constructions, borings and dredging. The shores of Southampton Water have been the scene of much activity of this nature during the past century, and a large quantity of information has accumulated concerning the submerged deposits, but surprisingly little has been published. -

401 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

401 bus time schedule & line map 401 Eastleigh View In Website Mode The 401 bus line (Eastleigh) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Eastleigh: 7:15 AM (2) Long Common: 4:20 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 401 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 401 bus arriving. Direction: Eastleigh 401 bus Time Schedule 42 stops Eastleigh Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 11:45 AM Boorley Park, Long Common Winchester Road, Botley Civil Parish Tuesday 7:15 AM Pear Tree, Boorley Green Wednesday 7:15 AM Oatlands Road, Boorley Green Thursday 7:15 AM Kestrel Close, Hedge End Friday 7:15 AM Uplands Farm, Botley Saturday Not Operational The Square, Botley 17 High Street, Botley Civil Parish C Of E Primary School, Botley 401 bus Info High Street, Hedge End Direction: Eastleigh Stops: 42 Brook Lane, Botley Trip Duration: 45 min Line Summary: Boorley Park, Long Common, Pear Brook Cottages, Broadoak Tree, Boorley Green, Oatlands Road, Boorley Green, Uplands Farm, Botley, The Square, Botley, C Of E Woodhouse Lane, Broadoak Primary School, Botley, Brook Lane, Botley, Brook Marvin Way, Hedge End Cottages, Broadoak, Woodhouse Lane, Broadoak, Maypole, Hedge End, Botleigh Grange Hotel, Wildern, Maypole, Hedge End Locke Road, Wildern, Birchwood Gardens, Grange Grange Road, Hedge End Park, St Lukes, Grange Park, Drummond Community Centre, Grange Park, Stirling Crescent, Grange Park, Botleigh Grange Hotel, Wildern Elliot Rise, Grange Park, Watkin Road, Grange Park, Martley Gardens, Grange -

Residents Associations

Residents Associations Ashurst Park Residents Association Bellevue Residents Association Bitterne Park Residents Association Blackbushe, Pembrey & Wittering Residents Association Blackbushe, Pembrey & Wittering Residents Association Channel Isles and District Tenants and Residents Association Chapel Community Association Clovelly Rd RA East Bassett Residents Association Flower Roads Residents and Tenants Association Freemantle Triangle Residents Association Graham Road Residents Association Greenlea Tenant and Residents Association Hampton Park Residents Association Harefield Tenants and Residents Association Highfield Residents Association Holly Hill Residents Association Hum Hole Project Itchen Estate Tenants and Residents Association Janson Road RA LACE Tenant and Residents Association Leaside Way Residents Association Lewis Silkin and Abercrombie Gardens Residents Association Lumsden Ave Residents Association Mansbridge Residents Association Maytree Link Residents Association Newlands Ave Residents Association Newtown Residents Association North East Bassett Residents Association Northam Tenants and Residents Association Old Bassett Residents Association Outer Avenue Residents Association Pirrie Close & Harland Crescent Residents Association Portswood Gardens Resident association Redbridge Residents Association Riverview Residents Association Rockstone Lane Residents Association Ropewalk RA Southampton Federation of Residents Associations Stanford Court Tenants and residents Association Thornbury Avenue & District Residents Association -

Public Transport

Travel Destinations and Operators Operator contacts Route Operator Destinations Monday – Saturday Sunday Bus operators Daytime Evening Daytime Bluestar Quay Connect Bluestar Central Station, WestQuay, Town Quay 30 mins 30 mins 30 mins 01202 338421 Six dials 1 Bluestar City Centre, Bassett, Chandlers Ford, Otterbourne, Winchester 15 mins 60 mins 30 mins www.bluestarbus.co.uk B1 Xelabus Bitterne, Sholing, Bitterne 3 per day off peak (Mon, Weds, Fri) City Red and First Solent Premier National Oceanography Centre, Town Quay, City Centre, Central 0333 014 3480 Inn U1 Uni-link 7/10 mins 20 mins 15 mins Station, Inner Avenue, Portswood, University, Swaythling, Airport www.cityredbus.co.uk Night service. Leisure World, West Quay, Civic Centre, London Road, 60 mins U1N Uni-link Royal South Hants Hospital, Portswood, Highfield Interchange, (Friday and Saturday nights) Salisbury Reds Airport, Eastleigh 01202 338420 City Centre, Inner Avenue, Portswood, Highfield, Bassett, W1 Wheelers 30/60 mins www.salisburyreds.co.uk W North Baddesley, Romsey I N T O N ST City Centre, Inner Avenue, Portswood, Swaythling, North Stoneham, 2 Bluestar 15 mins 60 mins 30 mins Eastleigh, Bishopstoke, Fair Oak Uni-link 2 First City Red City Centre, Central Station, Shirley, Millbrook 8/10 mins 20 mins 15 mins 023 8059 5974 www.unilinkbus.co.uk B2 Xelabus Bitterne, Midanbury, Bitterne 3 per day off peak (Mon, Weds, Fri) U2 Uni-link City Centre, Avenue Campus, University, Bassett Green, Crematorium 10 mins 20 mins 20 mins Wheelers Travel 023 8047 1800 3 Bluestar City Centre, -

Line Guide Elegant Facade Has Grade II Listed Building Status

Stations along the route Now a Grade II listed The original Southern Railway built a wonderful Art Deco Now Grade II listed, the main Eastleigh Station the south coast port night and day, every day, for weeks on b u i l d i n g , R o m s e y style south-side entrance. Parts of the original building still building is set well back from the opened in 1841 named end. Station* opened in platforms because it was intended remain, as does a redundant 1930’s signal box at the west ‘Bishopstoke Junction’. Shawford is now a busy commuter station but is also an T h e o r i g i n a l G r e a t 1847, and is a twin of to place two additional tracks end of the station. In 1889 it became access point for walkers visiting Shawford Down. W e s t e r n R a i l w a y ’ s Micheldever station. through the station. However the ‘ B i s h o p s t o k e a n d terminus station called The booking hall once had a huge notice board showing The station had a small goods yard that closed to railway The famous children’s extra lines never appeared! Eastleigh’ and in 1923 ‘Salisbury (Fisherton)’ passengers the position of all the ships in the docks, and had use in 1960, but the site remained the location of a civil author, the Reverend The construction of a large, ramped i t b e c a m e s i m p l y was built by Isambard the wording ‘The Gateway of the World’ proudly mounted engineering contractor’s yard for many years. -

SITE: 1 & 2 Gaters Mill, Mansbridge Road, Southampton, SO18 3HW

HEDGE END, WEST END & BOTLEY Monday 16 April 2007 Case Officer Rachel Illsley SITE: 1 & 2 Gaters Mill, Mansbridge Road, Southampton, SO18 3HW Ref. C/07/59322 Received: 19/02/2007 (17/04/2007) APPLICANT: Simon & Derek Bartlett PROPOSAL: Alterations & extensions to roof with addition of front & rear facing dormers to create 2 bed flat with 3 storey rear extension to provide staircase access & associated parking provision (amended scheme) AMENDMENTS: None RECOMMENDATION: Subject to: i) the satisfactory provision of developers' contributions towards social and recreational facilities, off-site public open space and transportation infrastructure in the local area. If these contributions are not secured within one month of the date of committee, the 16th May 2007, it is recommended that planning permission be refused on these grounds. PERMIT CONDITIONS AND REASONS: (1) The development hereby permitted must be begun within a period of three years beginning with the date on which this permission is granted. Reason: To comply with Section 91 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. (2) Details and samples of all external facing and roofing materials must be submitted to and approved in writing by the Local Planning Authority before development commences. The development must then accord with these approved details. Reason: To ensure that the external appearance of any building is satisfactory. (3) Details of Contractor's site hut location and any areas designated for the storage of building materials must be submitted to and approved in writing by the Local Planning Authority before development commences. The development must then accord with these approved details.