Macmillan's Romeo & Juliet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-2020 Season Overview JULY 2020

® 2019-2020 Season Overview JULY 2020 Report Summary The following is a report on the gender distribution of choreographers whose works were presented in the 2019-2020 seasons of the fifty largest ballet companies in the United States. Dance Data Project® separates metrics into subsections based on program, length of works (full-length, mixed bill), stage (main stage, non-main stage), company type (main company, second company), and premiere (non-premiere, world premiere). The final section of the report compares gender distributions from the 2018- 2019 Season Overview to the present findings. Sources, limitations, and company are detailed at the end of the report. Introduction The report contains three sections. Section I details the total distribution of male and female choreographic works for the 2019-2020 (or equivalent) season. It also discusses gender distribution within programs, defined as productions made up of full-length or mixed bill works, and within stage and company types. Section II examines the distribution of male and female-choreographed world premieres for the 2019-2020 season, as well as main stage and non-main stage world premieres. Section III compares the present findings to findings from DDP’s 2018-2019 Season Overview. © DDP 2019 Dance DATA 2019 - 2020 Season Overview Project] Primary Findings 2018-2019 2019-2020 Male Female n/a Male Female Both Programs 70% 4% 26% 62% 8% 30% All Works 81% 17% 2% 72% 26% 2% Full-Length Works 88% 8% 4% 83% 12% 5% Mixed Bill Works 79% 19% 2% 69% 30% 1% World Premieres 65% 34% 1% 55% 44% 1% Please note: This figure appears inSection III of the report. -

A SEASON of Dance Has Always Been About Togetherness

THE SEASON TICKET HOLDER ADVANTAGE — SPECIAL PERKS, JUST FOR YOU JULIE KENT, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR 2020/21 A SEASON OF Dance has always been about togetherness. Now more than ever, we cannot“ wait to share our art with you. – Julie Kent A SEASON OF BEAUTY DELIGHT WONDER NEXTsteps A NIGHT OF RATMANSKY New works by Silas Farley, Dana Genshaft, Fresh, forward works by Alexei Ratmansky and Stanton Welch MARCH 3 – 7, 2021 SEPTEMBER 30 – OCTOBER 4, 2020 The Kennedy Center, Eisenhower Theater The Harman Center for the Arts, Shakespeare Theatre The Washington Ballet is thrilled to present an evening of works The Washington Ballet continues to champion the by Alexei Ratmansky, American Ballet Theatre’s prolific artist-in- advancement and evolution of dance in the 21st century. residence. Known for his musicality, energy, and classicism, the NEXTsteps, The Washington Ballet’s 2020/21 season opener, renowned choreographer is defining what classical ballet looks brings fresh, new ballets created on TWB dancers to the like in the 21st century. In addition to the 17 ballets he’s created nation’s capital. With works by emerging and acclaimed for ABT, Ratmansky has choreographed genre-defining ballets choreographers Silas Farley, dancer and choreographer for the Mariinsky Ballet, the Royal Danish Ballet, the Royal with the New York City Ballet; Dana Genshaft, former San Swedish Ballet, Dutch National Ballet, New York City Ballet, Francisco Ballet soloist and returning TWB choreographer; San Francisco Ballet, The Australian Ballet and more, as well as and Stanton Welch, Artistic Director of the Houston Ballet, for ballet greats Nina Ananiashvili, Diana Vishneva, and Mikhail energy and inspiration will abound from the studio, to the Baryshnikov. -

2018/2019 Season

Saturday, April 6, 2019 1:00 & 6:30 pm 2018/2019 SEASON Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. Kevin McKenzie Kara Medoff Barnett ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Alexei Ratmansky ARTIST IN RESIDENCE STELLA ABRERA ISABELLA BOYLSTON MISTY COPELAND HERMAN CORNEJO SARAH LANE ALBAN LENDORF GILLIAN MURPHY HEE SEO CHRISTINE SHEVCHENKO DANIIL SIMKIN CORY STEARNS DEVON TEUSCHER JAMES WHITESIDE SKYLAR BRANDT ZHONG-JING FANG THOMAS FORSTER JOSEPH GORAK ALEXANDRE HAMMOUDI BLAINE HOVEN CATHERINE HURLIN LUCIANA PARIS CALVIN ROYAL III ARRON SCOTT CASSANDRA TRENARY KATHERINE WILLIAMS ROMAN ZHURBIN Alexei Agoudine Joo Won Ahn Mai Aihara Nastia Alexandrova Sierra Armstrong Alexandra Basmagy Hanna Bass Aran Bell Gemma Bond Lauren Bonfiglio Kathryn Boren Zimmi Coker Luigi Crispino Claire Davison Brittany DeGrofft* Scout Forsythe Patrick Frenette April Giangeruso Carlos Gonzalez Breanne Granlund Kiely Groenewegen Melanie Hamrick Sung Woo Han Courtlyn Hanson Emily Hayes Simon Hoke Connor Holloway Andrii Ishchuk Anabel Katsnelson Jonathan Klein Erica Lall Courtney Lavine Virginia Lensi Fangqi Li Carolyn Lippert Isadora Loyola Xuelan Lu Duncan Lyle Tyler Maloney Hannah Marshall Betsy McBride Cameron McCune João Menegussi Kaho Ogawa Garegin Pogossian Lauren Post Wanyue Qiao Luis Ribagorda Rachel Richardson Javier Rivet Jose Sebastian Gabe Stone Shayer Courtney Shealy Kento Sumitani Nathan Vendt Paulina Waski Marshall Whiteley Stephanie Williams Remy Young Jin Zhang APPRENTICES Jacob Clerico Jarod Curley Michael de la Nuez Léa Fleytoux Abbey Marrison Ingrid Thoms Clinton Luckett ASSISTANT ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Ormsby Wilkins MUSIC DIRECTOR Charles Barker David LaMarche PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR CONDUCTOR PRINCIPAL BALLET MISTRESS Susan Jones BALLET MASTERS Irina Kolpakova Carlos Lopez Nancy Raffa Keith Roberts *2019 Jennifer Alexander Dancer ABT gratefully acknowledges: Avery and Andrew F. -

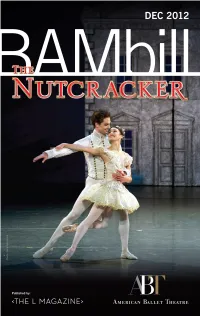

The Nutcracker

American Ballet Theatre Kevin McKenzie Rachel S. Moore Artistic Director Chief Executive Officer Alexei Ratmansky Artist in Residence HERMAN CORNEJO · MARCELO GOMES · DAVID HALLBERG PALOMA HERRERA · JULIE KENT · GILLIAN MURPHY · VERONIKA PART XIOMARA REYES · POLINA SEMIONOVA · HEE SEO · CORY STEARNS STELLA ABRERA · KRISTI BOONE · ISABELLA BOYLSTON · MISTY COPELAND ALEXANDRE HAMMOUDI · YURIKO KAJIYA · SARAH LANE · JARED MATTHEWS SIMONE MESSMER · SASCHA RADETSKY · CRAIG SALSTEIN · DANIIL SIMKIN · JAMES WHITESIDE Alexei Agoudine · Eun Young Ahn · Sterling Baca · Alexandra Basmagy · Gemma Bond · Kelley Boyd Julio Bragado-Young · Skylar Brandt · Puanani Brown · Marian Butler · Nicola Curry · Gray Davis Brittany DeGrofft · Grant DeLong · Roddy Doble · Kenneth Easter · Zhong-Jing Fang · Thomas Forster April Giangeruso · Joseph Gorak · Nicole Graniero · Melanie Hamrick · Blaine Hoven · Mikhail Ilyin Gabrielle Johnson · Jamie Kopit · Vitali Krauchenka · Courtney Lavine · Isadora Loyola · Duncan Lyle Daniel Mantei · Elina Miettinen · Patrick Ogle · Luciana Paris · Renata Pavam · Joseph Phillips · Lauren Post Kelley Potter · Luis Ribagorda · Calvin Royal III · Jessica Saund · Adrienne Schulte · Arron Scott Jose Sebastian · Gabe Stone Shayer · Christine Shevchenko · Sarah Smith* · Sean Stewart · Eric Tamm Devon Teuscher · Cassandra Trenary · Leann Underwood · Karen Uphoff · Luciana Voltolini Paulina Waski · Jennifer Whalen · Katherine Williams · Stephanie Williams · Roman Zhurbin Apprentices Claire Davison · Lindsay Karchin · Kaho Ogawa · Sem Sjouke · Bryn Watkins · Zhiyao Zhang Victor Barbee Associate Artistic Director Ormsby Wilkins Music Director Charles Barker David LaMarche Principal Conductor Conductor Ballet Masters Susan Jones · Irina Kolpakova · Clinton Luckett · Nancy Raffa * 2012 Jennifer Alexander Dancer ABT gratefully acknowledges Avery and Andrew Barth for their sponsorship of the corps de ballet in memory of Laima and Rudolph Barth and in recognition of former ABT corps dancer Carmen Barth. -

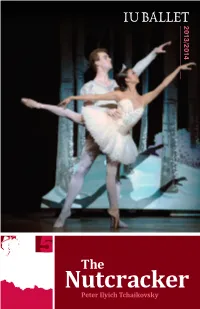

Nutcracker 5 Three Hundred Eighty-Second Program of the 2013-14 Season ______

2013/2014 5 The Nutcracker Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Three Hundred Eighty-Second Program of the 2013-14 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater as its 55th annual production of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet in Two Acts Scenario by Michael Vernon, after Marius Petipa’s adaptation of the story “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffman Michael Vernon, Choreography Philip Ellis, Conductor C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Design Patrick Mero, Lighting Design The Nutcracker was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892. ____________ Musical Arts Center Thursday vening,E December Fifth, Seven O’Clock Friday Evening, December Sixth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, December Seventh, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, December Seventh, Eight O’Clock Sunday Afternoon, December Eighth, Two O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Nutcracker Michael Vernon, Artistic Director Choreography by Michael Vernon Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Doricha Sales, Ballet Mistress & Children’s Ballet Mistress The children performing in The Nutcracker are from the Jacobs School of Music Pre-College Ballet Program. MENAHEM PRESSLER th 90BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION Friday, Dec. 13 8pm | Musical Arts Center | $10 Students $20 Regular The Jacobs School of Music will celebrate the 90th birthday of Distinguished Professor Menahem Pressler with a concert that includes performances by violinist Daniel Hope, cellist David Finckel, pianist Wu Han, the Emerson String Quartet, and the master himself! Chat online with the legendary pianist! Thursday, Dec. 12 | 8pm music.indiana.edu/celebrate-pressler For concert tickets, visit the Musical Arts Center Box Office: (812) 855-7433, or go online to music.indiana.edu/boxoffice. -

Copyright Marilyn J. La Vine © 2007 New York –

Copyright Marilyn J. La Vine © 2007 New York - Tous droits réservés - # Symbol denotes creation of role Commencing with the year 1963, only the first performance of each new work to his repertoire is listed. London March 2,1970 THE ROPES OF TIME # The Traveler The Royal Ballet; Royal Opera House With: Monica Mason, Diana Vere C: van Dantzig M: Boerman London July 24,1970 'Tribute to Sir Frederick Ashton' Farewell Gala. The Royal LES RENDEZ-VOUS Ballet,- Royal Opera House Variation and Adagio of Lovers With: Merle Park Double debut evening. C: Ashton M: Auber London July 24,1970 APPARITIONS Ballroom Scene The Royal Ballet; Royal Opera House The Poet Danced at this Ashton Farewell Gala only. With: Margot Fonteyn C: Ashton M: Liszt London October 19, 1970 DANCES AT A GATHERING Lead Man in Brown The Royal Ballet; Royal Opera House With: Anthony Dowell, Antoinette Sibley C: Robbins M: Chopin Marseille October 30, 1970 SLEEPING BEAUTY Prince Desire Ballet de L'Opera de Morseille; Opera Municipal de Marseille With: Margot Fonteyn C: Hightower after Petipa M: Tchaikovsky Berlin Berlin Ballet of the Germon Opera; Deutsche Opera House November 21, 1970 Copyright Marilyn J. La Vine © 2007 New York – www.nureyev.org Copyright Marilyn J. La Vine © 2007 New York - Tous droits réservés - # Symbol denotes creation of role SWAN LAKE Prince Siegfried With: Marcia Haydee C: MacMillan M: Tchaikovsky Brussels March 11, 1971 SONGS OF A WAYFARER (Leider Eines Fahrenden Gesellen) # Ballet of the 20#, Century; Forest National Arena The Wanderer With: Paolo Bortoluzzi C: Bejart M: Mahler Double debut evening. -

(With) Shakespeare (/783437/Show) (Pdf) Elizabeth (/783437/Pdf) Klett

11/19/2019 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation ISSN 1554-6985 V O L U M E X · N U M B E R 2 (/current) S P R I N G 2 0 1 7 (/previous) S h a k e s p e a r e a n d D a n c e E D I T E D B Y (/about) E l i z a b e t h K l e t t (/archive) C O N T E N T S Introduction: Dancing (With) Shakespeare (/783437/show) (pdf) Elizabeth (/783437/pdf) Klett "We'll measure them a measure, and be gone": Renaissance Dance Emily Practices and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (/783478/show) (pdf) Winerock (/783478/pdf) Creation Myths: Inspiration, Collaboration, and the Genesis of Amy Romeo and Juliet (/783458/show) (pdf) (/783458/pdf) Rodgers "A hall, a hall! Give room, and foot it, girls": Realizing the Dance Linda Scene in Romeo and Juliet on Film (/783440/show) (pdf) McJannet (/783440/pdf) Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet: Some Consequences of the “Happy Nona Ending” (/783442/show) (pdf) (/783442/pdf) Monahin Scotch Jig or Rope Dance? Choreographic Dramaturgy and Much Emma Ado About Nothing (/783439/show) (pdf) (/783439/pdf) Atwood A "Merry War": Synetic's Much Ado About Nothing and American Sheila T. Post-war Iconography (/783480/show) (pdf) (/783480/pdf) Cavanagh "Light your Cigarette with my Heart's Fire, My Love": Raunchy Madhavi Dances and a Golden-hearted Prostitute in Bhardwaj's Omkara Biswas (2006) (/783482/show) (pdf) (/783482/pdf) www.borrowers.uga.edu/7165/toc 1/2 11/19/2019 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation The Concord of This Discord: Adapting the Late Romances for Elizabeth the -

The Annual 12 Night Party

President: Vice President: No. 485 - December 2013 Simon Russell Beale CBE Nickolas Grace Price 50p when sold Cutting the cake at the Vic-Wells’ 12th Night Party 2011 - Freddie Fox 2012 - Janie Dee 2013 - Clive Rowe ... but who will be there in 2014 to do this important operation? Why not come along and find out? As you can see, there is a very special cake made for the occasion and the guests certainly enjoy the ceremony. We make sure that everybody will get a slice to enjoy. Don’t be left out, book now! The Annual 12th Night Party Our annual Twelfth Night Party will be held at the Old Vic on Saturday, 4th January 2014 from 5.00pm to 6.30pm in the second circle bar area. Tickets are £6 for Members and £7.50 for Non-Members. Please write for tickets, enclosing a stamped, self-addressed envelope, to: Ruth Jeayes, 185 Honor Oak Road, London SE23 3RP (0208 699 2376) Stuttgart Ballet at Sadler’s Wells Report by Richard Reavill The Stuttgart Ballet is one of the world’s major international ballet companies, but it does not often visit the UK. It did make a short trip to Sadler’s Wells in November with two p r o g r a m m e s a n d f i v e performances over four days. The first one, Made in Germany, featured excerpts from works choreographed in Germany for t h e c o m p a n y . T h o u g h presented in three groups with two intervals, (like a triple bill), there were thirteen items, mostly pas-de-deux and solos, and only one piece, given last, for a larger group of dancers. -

93 the Cleopatra Ballerina Who Stays

SUNDAY TELEGRAPH March 21 1993 The Cleopatra ballerina who stays out in the cold Photo: Matthew Ford In a rare interview the great ballerina Lynn Seymour tells Ismene Brown why she's so wary of public attention A LOT of typewriter ribbon has frayed on the subject of Lynn Seymour. She is 'the greatest dramatic dancer of the era', according to Dame Ninette de Valois. Yet when she joined English National Ballet in 1989, one dancer told a newspaper contemptuously, 'She teaches with a beer can in one hand and a cigarette in the other. Who needs that?' Her image has see-sawed wildly between genius and Bad Girl. Both sides of the image are fed with plenty of material: consistently awestruck reviews of her dancing - and a considerable amount of backstage bitchery about her weight problems. Or drink problems. Or temper problems. Or man problems. Or money problems. These in turn were said to explain her absences from the stage. Where Fonteyn and Sibley sailed through their careers like galleons - in public, at least - Seymour's ship was always taking in water. It is unsurprising, then, that over the years she has avoided the press like the plague. I hadn't realised quite how scarred she is by publicity - or at least by her own view of what her public image is - until I met her last week. She had refused interview requests for her own recent appearances with Scottish Ballet as Lady Capulet, and with Northern Ballet Theatre in A Simple Man, but she agreed to 'do it for Derek's thing' - Derek being the film director Derek Jarman, who asked her to play the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova in his new film, Wittgenstein. -

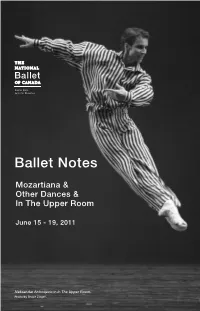

Ballet Notes

Ballet Notes Mozartiana & Other Dances & In The Upper Room June 15 - 19, 2011 Aleksandar Antonijevic in In The Upper Room. Photo by Bruce Zinger. Orchestra Violins Bassoons Benjamin BoWman Stephen Mosher, Principal Concertmaster JerrY Robinson LYnn KUo, EliZabeth GoWen, Assistant Concertmaster Contra Bassoon DominiqUe Laplante, Horns Principal Second Violin Celia Franca, C.C., Founder GarY Pattison, Principal James AYlesWorth Vincent Barbee Jennie Baccante George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Derek Conrod Csaba KocZó Scott WeVers Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Sheldon Grabke Artistic Director Executive Director Xiao Grabke Trumpets David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. NancY KershaW Richard Sandals, Principal Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk Mark Dharmaratnam Principal Conductor YakoV Lerner Rob WeYmoUth Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer JaYne Maddison Trombones Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Ron Mah DaVid Archer, Principal YOU dance / Ballet Master AYa MiYagaWa Robert FergUson WendY Rogers Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne DaVid Pell, Bass Trombone Filip TomoV Senior Ballet Master Richardson Tuba Senior Ballet Mistress Joanna ZabroWarna PaUl ZeVenhUiZen Sasha Johnson Aleksandar AntonijeVic, GUillaUme Côté*, Violas Harp Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, LUcie Parent, Principal Zdenek KonValina, Heather Ogden, Angela RUdden, Principal Sonia RodrigUeZ, Piotr StancZYk, Xiao Nan YU, Theresa RUdolph KocZó, Timpany Bridgett Zehr Assistant Principal Michael PerrY, Principal Valerie KUinka Kevin D. Bowles, Lorna Geddes, -

Live from Covent Garden Announcement 19.06.20

19 June 2020 #OurHouseToYourHouse The Royal Opera House announces Live from Covent Garden, Saturday 27 June The Royal Opera House is delighted to continue its #OurHouseToYourHouse programme of online broadcasts, musical masterclasses and cultural highlights, created for audiences across the globe. As we look forward to the second in the series of three Live from Covent Garden concerts this Saturday, the Royal Opera House is proud to announce the programming for the third concert on Saturday 27 June at 7.30pm BST, broadcast live via the ROH website from its world-famous Covent Garden home. A celebration of especially curated ballet and opera, the Live from Covent Garden concerts are the first live performances from the Royal Opera House since the building closed its doors to the public on 17 March. Join us behind the scenes as we open our theatre to a select group of musicians, artists and performers, direct from our house to your house. The third concert will be hosted by Katie Derham and The Royal Opera’s Music Director, Antonio Pappano, joined by soloists of the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. Singers from the ROH Jette Parker Young Artists programme, will present work from George Frideric Handel, Gaetano Donizetti, Gioachino Rossini, Giuseppe Verdi, George Gershwin and more. The Jette Parker Young Artists will include Andrés Presno, Filipe Manu, Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha, Stephanie Wake-Edwards, Patrick Milne and Edmund Whitehead, and Link Artist Blaise Malaba. First Soloists of The Royal Ballet Fumi Kaneko and Reece Clarke will perform the lyrical central pas de deux from Kenneth MacMillan’s Concerto. -

Compton Stage

Compton Stage 10:30 AM Bear Hill Bluegrass Bear Hill Bluegrass takes pride in performing traditional bluegrass and gospel, while adding just the right mix of classic country and comedy to please the audience and have fun. They play the familiar bluegrass, gospel and a few country songs that everyone will recognize, done in a friendly down-home manner on stage. The audience is involved with the band and the songs throughout the show. 11:10 AM T-Mart Rounders The T-Mart Rounders is an old-time trio that consists of Kevin Chesser on claw-hammer banjo, vocalist Jesse Milnes on fiddle and Becky Hill on foot percussion. They re-envision percussive dance as another instrument and arrange traditional old-time tunes using foot percussion as if it were a drum set. All three musicians have spent significant time in West Virginia learning from master elder musicians and dancers. Their goal with this project is to respect the old-time music tradition while pushing its boundaries. In addition to performing, they teach flatfooting/ clogging, fiddle, claw-hammer banjo, guitar and songwriting workshops, and call/play at square dance. 11:50 AM Hickory Bottom Band Tight three-part harmonies, solid pickin’ and lots of fun are the hallmarks of this fine Western Pennsylvania-based band. Every member has a rich musical history in a variety of genres, so the material ranges from well-known and obscure bluegrass classics to grassy versions of select radio hits from the past 40 years. No matter the music’s source, it’s “all bluegrass” from this talented bunch! 12:30 PM Davis & Elkins College Appalachian Ensemble The Davis & Elkins College Appalachian Ensemble, a student performance group led by string band director Emily Miller and dance director William Roboski, is dedicated to bringing live traditional music and dance to audiences in West Virginia and beyond.