TASMANIA's MOUNTAINS. M. Tatham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glacial Map of Nw

TASMANI A DEPARTMENT OF MIN ES GEOLOGICAL SURV EY RECORD No.6 .. GLACIAL MAP OF N.W. - CEN TRAL TASMANIA by Edward Derbyshire Issued under the authority of The Honourable ERIC ELLIOTT REECE, M.H.A. , Minister for Mines for Tasmania ......... ,. •1968 REGISTERED WITH G . p.a. FOR TRANSMISSION BY POST A5 A 800K D. E . WIL.KIN SOS. Government Printer, Tasmania 2884. Pr~ '0.60 PREFACE In the published One Mile Geological Maps of the Mackintosh. Middlesex, Du Cane and 8t Clair Quadrangles the effects of Pleistocene glaciation have of necessity been only partially depicted in order that the solid geology may be more clearly indicated. However, through the work of many the region covered by these maps and the unpublished King Wi11 iam and Murchison Quadrangles is classic both throughout AustraHa and Overseas because of its modification by glaciation. It is, therefore. fitting that this report of the most recent work done in the region by geomorphology specialist, Mr. E. Derbyshire, be presented. J. G. SYMONS, Director of Mmes. 1- CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 11 GENERAL STR UCT UIIE AND MOIIPHOLOGY 12 GLACIAL MORPHOLOGY 13 Glacial Erosion ~3 Cirques 14 Nivation of Cirques 15 Discrete Glacial Cirques 15 Glacial Valley-head Cirques 16 Over-ridden Cirques 16 Rock Basin s and Glacial Trou~hs 17 Small Scale Erosional Effects 18 Glacial Depositional Landforms 18 GLACIAL SEDIMENTS 20 Glacial Till 20 Glacifluvial Deposits 30 Glacilacustrine Deposits 32 STIIATIGIIAPHY 35 REFERENCES 40 LIST OF FIGURES PAGE Fig. 1. Histogram showing orientation of the 265 cirques shown on the Glacial Map 14 Fig. -

2013 June Newsletter

President Dick Johnstone 50220030 Vice President Russell Shallard Sunraysia Secretary Roger Cornell 50222407 Treasurer Barb Cornell 50257325 Bushwalkers Quarter Master Roger Cornell 50257325 News Letter Editor June 2013 Barb Cornell 50257325 PO Box 1827 Membership Fees MILDURA 3502 $40 Per Person Ph: 03 50257325 Affiliated with: Subs due July each year Website: www.sunbushwalk.net.au In this issue: Cradle Mountain Assent 2014 Planned Trips by the Milton Rotary Club of New Zealand Calendar of upcoming events Cradle Mountain Assent 18th – 24th April 2013 A few Facts: Cradle Mountain rises 934 metres (3,064 ft) above the glacially formed Dove Lake, Lake Wilks, and Crater Lake. The mountain itself is named after its resemblance to a gold mining cradle. It has four named summits: In order of height: Cradle Mountain 1,545 mtrs (5,069 ft) Smithies Peak 1,527 mtrs (5,010 ft) Weindorfers Tower 1,459 mtrs (4,787 ft) Little Horn 1,355 mtrs (4,446 ft) When it was proposed to tackle Cradle Mountain on the 1st day of our week’s walking, Verna was heard to ponder the wisdom of such an attempt on the first day. As on a previous trip, when our group undertook to climb Mt Strzelecki on day one on Flinders Island, it took the remaining week to recover! Fortunately not many of our current party heard her. So off we set at 8.30am to climb to Kitchen Hut via the Horse Track around Crater Lake from our base at Waldheim Cabins (950 metres). It was not long into the walk when I, for one, was thankful to have gloves. -

TWWHA Walking Track Management Strategy 1994 Vol 1

Walking Track Management Strategy for the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Volume I Main Report January 1994 1 Summary The Walking Track Management Strategy is a strategy developed by the Tasmanian Parks & Wildlife Service for the management of walking tracks and walkers in and adjacent to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA), in accordance with the recommendations of the World Heritage Area Management Plan. Key management issues in the region include the extensive deterioration of existing walking tracks and the unplanned development of new walking tracks in many areas. Campsite impacts, crowding, pollution and broadscale trampling damage to vegetation and soils are also creating serious problems in some areas. The Strategy has been prepared on the basis of an extensive literature survey and an inventory of tracks and track conditions throughout the WHA. Research has also been undertaken to assess usage levels, usage trends and user attitudes and characteristics throughout the WHA. The three-volume document includes: • a summary of the findings of the literature survey (section 2 and appendix B); • a description of the method used to compile the inventory of tracks and track conditions, and a summary of the findings of the inventory (section 3); • a summary of available information on usage levels, usage trends, user characteristics and attitudes and social impacts throughout the WHA (section 4 and appendix C); • an assessment of the opportunity spectrum for bushwalking in and adjacent to the WHA (section 5 and appendix -

OVERLAND TRACK TOUR GRADE: Well Defined and Wide Tracks on Easy to WORLD HERITAGE AREA Moderate Terrain, in Slightly Modified Natural Environments

FACTSHEET DURATION: 8 days OVERLAND TRACK TOUR GRADE: Well defined and wide tracks on easy to WORLD HERITAGE AREA moderate terrain, in slightly modified natural environments. You will require a modest level of OFF PEAK SEASON – MAY TO OCTOBER fitness. Recommended for beginners. The world renowned Overland Track is usually included in any list of the world’s great walks, and justifiably so. It showcases the highlights of Tasmania’s spectacular landforms and flora in a memorable 80km trek from Lake St Clair to Cradle Mountain. Discover glacial remnants of cirques, lakes and tarns; temperate rainforests of myrtle beech and sassafras, laurel and leatherwood; jagged mountain peaks of fluted dolerite columns (including Tasmania’s highest – Mt Ossa at 1617m); stark alpine moorlands and deep gorges and waterfalls. ITINERARY & TOUR DESCRIPTION Our tour starts at Lake St Clair, a through open eucalypt forest that Day 3: glacial lake 220m deep, 14km long, changes gradually to myrtle beech. Windy Ridge Hut to Kia Ora Hut and culminates at the dramatic Our campsite at Narcissus Hut is We make an early start for the short Cradle Mountain. This approach adjacent to the Narcissus River where but steep climb to the Du Cane Gap gives a different perspective to this you have the opportunity for a swim on the Du Cane Range. We catch our experience as the walk leads to ever to freshen up before dinner. breath here in the dense forest, and more dramatic alpine scenery as we then proceed to the day’s sidetrack proceed through temperate rainforest Day 2: highlights of Hartnett, Fergusson from our start at Lake St Clair to the Narcissus Hut to Windy Ridge Hut and D’Alton Falls in the spectacularly finish at Cradle Mountain. -

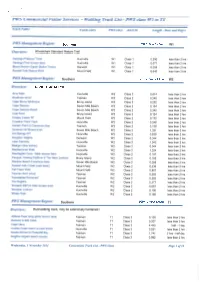

Walking Track List - PWS Class Wl to T4

PWS Commercial Visitor Services - Walking Track List - PWS class Wl to T4 Track Name FieldCentre PWS class AS2156 Length - Kms and Days PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: VV1 Overview: Wheelchair Standard Nature Trail Hastings Platypus Track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.290 less than 2 hrs Hastings Pool access track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.077 less than 2 hrs Mount Nelson Signal Station Tracks Derwent W1 Class 1 0.059 less than 2 hrs Russell Falls Nature Walk Mount Field W1 Class 1 0.649 less than 2 hrs PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: W2 Overview: Standard Nature Trail Arve Falls Huonville W2 Class 2 0.614 less than 2 hrs Blowhole circuit Tasman W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Cape Bruny lighthouse Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.252 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.154 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Beach Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.345 less than 2 hrs Coal Point Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.124 less than 2 hrs Creepy Crawly NT Mount Field W2 Class 2 0.175 less than 2 hrs Crowther Point Track Huonville W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Garden Point to Carnarvon Bay Tasman W2 Class 2 3.138 less than 2 hrs Gordons Hill fitness track Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 1.331 less than 2 hrs Hot Springs NT Huonville W2 Class 2 0.839 less than 2 hrs Kingston Heights Derwent W2 Class 2 0.344 less than 2 hrs Lake Osbome Huonville W2 Class 2 1.042 less than 2 hrs Maingon Bay lookout Tasman W2 Class 2 0.044 less than 2 hrs Needwonnee Walk Huonville W2 Class 2 1.324 less than 2 hrs Newdegate Cave - Main access -

OVERLAND TRACK TOUR GRADE: Well Defined and Wide Tracks on Easy to WORLD HERITAGE AREA Moderate Terrain, in Slightly Modified Natural Environments

FACTSHEET DURATION: 6 days OVERLAND TRACK TOUR GRADE: Well defined and wide tracks on easy to WORLD HERITAGE AREA moderate terrain, in slightly modified natural environments. You will require a modest level of fitness. Recommended for beginners. CRADLE MOUNTAIN – LAKE ST CLAIR NATIONAL PARK The world renowned Overland Track is usually included in any list of the world’s great walks, and justifiably so. It showcases the highlights of Tasmania’s spectacular landforms and flora in a memorable 80km trek from Lake St Clair to Cradle Mountain. Discover glacial remnants of cirques, lakes and tarns; temperate rainforests of myrtle beech and sassafras, laurel and leatherwood; jagged mountain peaks of fluted dolerite columns (including Tasmania’s highest – Mt Ossa at 1617m); stark alpine moorlands and deep gorges and waterfalls. In the peak season, our tour starts at Dove Lake below the dramatic Cradle Mountain and finishes at Cynthia Bay on Lake St Clair, a glacial lake 220m deep, 14km long. At other times, we start at Lake St Clair and finish at Cradle Mountain, and spend a night in Pine Valley as an early side-trip on the way to Windy Ridge and a day base-camping at Waterfall Valley. ITINERARY & TOUR DESCRIPTION Day 1: the glacially formed lakes and tarns, This is alpine Tasmania at its best, BCT to Cradle Valley and then continue on to Kitchen Hut and you will long retain vivid and Waterfall Valley from where we have the opportunity memories of this marvellous area. We make an early start from BCT and to scramble up the dolerite of Cradle travel to Cradle Valley via the bleak Mountain (1545m). -

Report of the Sevretary of Mines for 1892-3

(No. 50.) 18 9 3. PARLIAMENT OF TASMANIA. REPORT OF THE SECRETARY OF 1\1INES FOR 189"2-3 : INCLUDING REPORTS OF THE INSPECTORS OF MINES, &c. Presented to both Houses of Parliament by His Excellency's Comnian<l. T .ASMAN I A. R 0 R T OF THE S E, C R E T A R Y ·0 F ·M I N E s: FOR INCLUDING THE REPORTS OF THE INSPECTO_RS OF MINES,,. THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEYOR, THE MOU~T CAMERON WATER-RACE BOARD, &c. I . I m:afjmanta: . WILLIAM GRAHAME, JUN., GOVERNMENT .PRINTER, HOBART~ 18 9 3. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page Annual Report of Secretary of Mines ............................................... 5 Gold: Table-Comparative Yield ..................................................... 10 ,, Quantity obtained from Quartz ................................. : .... 10 Coal: ,, Quantity and Value raised ................... : ........................ 10 Tin: ,, Comparative Statement Quantity exported ....................... 11 Min~rs employed: Number of ............ , ........................................... 11 Area of Land leased .................................................................... 11 -12 Revenue, Statement of Mining ........................................................ 12. Dividends paid : Gold Mining Companies ......................................... 12 Tin ditto .............................................................. 13 Silver ditto ........................................................... 13 Mine Managers' Examination Papers ................................. : ............. 14 - 18 Reports of Commissioners ............. , ............................................... -

Overland Track - Tasmania Lens 1/125S @ F/14, ISO 200, Tripod, Cable Release

Feature: Preparing For A Photo Trek LEFT Mt Geryon sunset, Tasmania. I’d been photographing fungi with my macro lens, when I came across this scene. My instinct was to pick up my camera, choose my settings, compose my shot and fire off a few shots. This scene lasted | only for a few minutes. Sometimes you have to move quickly. Nikon D700, 150mm f/2.8 Sigma macro lens, 1/8000s @ f/5.6, ISO 1000, hand-held. BELOW Spectacular Barn Bluff. I saw it in the distance and instantly knew that there was a photo opportunity to be had. Photo Trekking Once I was close to the two foreground boulders, I set my tripod low to the ground. Nikon D700, using a 16-35mm f/4 Overland Track - Tasmania lens 1/125s @ f/14, ISO 200, tripod, cable release. Wilderness and nature shooter Michael Snedic outlines how you can plan and undertake a bushwalk and also come back with some great images. ne of the great things about photography is that your camera is Oportable and you can take photos almost anywhere. Here I want to explain the best way to prepare for and execute a photo trek into the bush. Australia is a lucky country in many ways, not least of all because it has so much great bush terrain. It’s fantastic to be able to get photographs of it, but hiking deep into the wilderness can be a real challenge. It is achievable though, if you plan and prepare for your trip properly. I describe a ‘photo trek’ as an expedition where you hike for a period of days or sometimes even a week, camp overnight at various spots, and take with you all the provisions you’ll need. -

Geology of the Cradle Mountain Reserve by I

ECONOMIC AND GENERAL GEOLOGY. 7 3 TR".73.78 Geology of the Cradle Mountain Reserve by I. B. Jennings ' Three main solid rock stratigraphic units comprise the big majority of the Cradle Mountain reserve area. These 81'e: (1) The Precambrian basement. (2) Permo-Triassic sediments. (3) Jurassic dolerite. However, the solid geology of the area is frequently ob3cllred beneath extensive deposits of superficial materiaL The most im portant of these deposits being (in order)- (1) Pleistocene glacial and peri-glacial deposits. (2) Quaternary talus and serees. (3) Recent soils and peaty soils. Solid Geology Basically the geology of the area is simple. It consists of a complexly folded Precambrian basement oveTlalp with violent uncon formity by gently dipping sediments of Permian and Triassic age. Later, immense sheets of dolerite were intruded into the Permo Triassic rocks and along the Permian-Precambrian unconformity. The dolerite intrusions are overwhelmingly sill-like in character and are in excess of 1,000 feet in thickness. Originally they possibly reached a thickness of 1,500 feet. The ,post-Permian structure consists of block faulting, first dur ing the dolerite intrusions and then again during the Lower Tertiary. That is, the Permian and younger rocks have been tilted as blocks and not, except in s'Jecia1 cases near the boundary faults, folded into anticlines and synchnes. To understand the geology of the area then, it is necessary only to think of a giant sandwich consisting of at the bottom a Precambrian basement, in the middle Permo-Triassic sediments and on top thick dolerite sills. The pre-Permian surface on the Precambrian rocks is ,mly gently undulating. -

Mineral Deposits of Tasmania

147°E 144°E 250000mE 300000mE 145°E 350000mE 400000mE 146°E 450000mE 500000mE 550000mE 148°E 600000mE CAPE WICKHAM MINERAL DEPOSITS AND METALLOGENY OF TASMANIA 475 ! -6 INDEX OF OCCURRENCES -2 No. REF. No. NAME COMMODITY EASTING NORTHING No. REF. No. NAME COMMODITY EASTING NORTHING No. REF. No. NAME COMMODITY EASTING NORTHING No. REF. No. NAME COMMODITY EASTING NORTHING No. REF. No. NAME COMMODITY EASTING NORTHING 1 2392 Aberfoyle; Main/Spicers Shaft Tin 562615 5388185 101 2085 Coxs Face; Long Plains Gold Mine Gold 349780 5402245 201 1503 Kara No. 2 Magnetite 402735 5425585 301 3277 Mount Pelion Wolfram; Oakleigh Creek Tungsten 419410 5374645 401 240 Scotia Tin 584065 5466485 INNER PHOQUES # 2 3760 Adamsfield Osmiridium Field Osmium-Iridium 445115 5269185 102 11 Cullenswood Coal 596115 5391835 202 1506 Kara No. 2 South Magnetite 403130 5423745 302 2112 Mount Ramsay Tin 372710 5395325 402 3128 Section 3140M; Hawsons Gold 414680 5375085 SISTER " 3 2612 Adelaide Mine; Adelaide Pty Crocoite 369730 5361965 103 2593 Cuni (Five Mile) Mineral Field Nickel 366410 5367185 203 444 Kays Old Diggings; Lawries Gold 375510 5436485 303 1590 Mount Roland Silver 437315 5409585 403 3281 Section 7355M East Coal 418265 5365710 The Elbow 344 Lavinia Pt ISLAND BAY 4 4045 Adventure Bay A Coal 526165 5201735 104 461 Cuprona Copper King Copper 412605 5446155 204 430 Keith River Magnesite Magnesite 369110 5439185 304 2201 Mount Stewart Mine; Long Tunnel Lead 359230 5402035 404 3223 Selina Eastern Pyrite Zone Pyrite 386310 5364585 5 806 Alacrity Gold 524825 5445745 -

Ronny Creek to Waterfall Valley

Ronny Creek to Waterfall Valley 4 h to 6 h 5 10.8 km ↑ 535 m Very challenging One way segment ↓ 384 m The Overland Track starts by guiding you through some amazingly diverse and spectacular landscapes. You start from the bus stop and car park at Ronny Creek, then wander for a few hundred meters through the buttongrass plains beside Ronny Creek. After this the uphill starts, it is very steep in places, take your time and enjoy the views. You will pass Crater Falls in a lovely rainforest before emerging at the mouth of the glacier-carved Crater Lake. The climbing continues up from here, with chains to assist one short rocky scramble up to Marion's Lookout and the amazing views over Dove Lake. Continue along the Overland Track to Kitchen Hut (a great lunch spot) where there is the potential side trip to Cradle Mountain. The Overland Track then continues 'behind' Cradle Mountain before wandering down the lovely Waterfall Valley. Before heading down to Waterfall valley is the option challenging side trip to Barn Bluff. One of the more challenging days on track with a stunning environment, start early and take your time to soak it all up. Let us begin by acknowledging the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we travel today, and pay our respects to their Elders past and present. This is part of longer journey and can not be completed on it is own. Full journey: The Overland Track 1,330 1,238 1,146 1,054 962 870 0 m 6 km 7 km 540 m 5.9x 1.1 km 1.6 km 2.2 km 2.7 km 3.3 km 3.8 km 4.3 km 4.9 km 5.4 km 6.5 km 7.6 km 8.1 km 8.7 km 9.2 km 9.8 km 10.3 km 10.8 km Class 5 of 6 Rough unclear track Quality of track Formed track, with some branches and other obstacles (3/6) Gradient Very steep (4/6) Signage Clearly signposted (2/6) Infrastructure Limited facilities, not all cliffs are fenced (3/6) Experience Required Some bushwalking experience recommended (3/6) Weather Forecasted & unexpected severe weather likely to have an impact on your navigation and safety (5/6) Getting to the start: From Cradle Mountain Road, C132, Cradle Mountain. -

Overland Track Itinerary

Overland Track Itinerary Welcome to Tasmanian Hikes Thank you for enquiring into our tours and activities. At Tasmanian Hikes we specialize in small group trekking. This tour is limited to groups of 9 clients, to reduce our environmental impact and to maximize your adventure experience. On all our tours our guides will share their skills and experiences with you, so that we can best develop your own bushwalking skills and ensure that your objectives are met. Our itineraries have been designed and researched by experienced guides. Each day is broken down into manageable legs to give you the best possible experience plus time out to relax and explore the beauty of your surroundings. Our campfire cuisine, where able is prepared using fresh ingredients and our meals will satisfy the heartiest of appetites. Tasmanian Hikes utilize the services of local businesses whenever we can thus generating economic benefits for the host communities that we visit. We invite you to join us on our treks and look forward to guiding you through your wilderness adventure. Joining Instruction At the booking stage of the tour we will provide you with the how, when and where of the tour. This will include booking information, personal bushwalking equipment list, our environmental policy for the National Park, travel and accommodation information. Itinerary Please enjoy reading the trek itinerary below. If you require any further information please do not hesitate to call us. Day 1: Ronny Creek to Waterfall Valley – 10km, 3-5 hours After driving from Launceston your walk starts at Ronny Creek in Cradle Valley, and crosses a small button grass plain before rising up to the expansive views from Marion’s Lookout.