E90: the Roller Coaster Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden Ticket Awards • September 16 & 17, 2011 COURTESY S

GOLDEN TICKET BONUS ISSUE TM www.GoldenTicketAwards.com Vol. 15 • Issue 6.2 SEPTEMBER 2011 Holiday World hosts Golden Ticket event for third time Amusement Today sees the biggest voter response in survey history 2011 . P . I GOLDEN TICKET . V AWARDS BEST OF THE BEST! Holiday World & Splashin’ Safari Host Park • 2011 Golden Ticket Awards • September 16 & 17, 2011 COURTESY S. MADONNA HORCHER STORY: Tim Baldwin strate the big influx of additional voters. [email protected] Tabulating hundreds of ballots can seem SANTA CLAUS, Indiana — It was Holiday like a somewhat tedious and daunting task, World’s idea for Amusement Today to pres- but a few categories were such close races, ent the Golden Ticket Awards live in 2000. that a handful of winners were not determined The ceremony was on the simple side, and until the very last ballots in the last hour of now over a decade later, the park welcomes tabulation. These ‘nail biters’ always keep us AT for the third time. A lot has changed since on our toes that there is never a guarantee of that time, as the Golden Ticket Awards cere- any category. mony has grown into a popular industry event, The dedication of our voters is also admi- filled with networking opportunities and occa- rable. People have often gone to great lengths sions to see what is considered the best in the to make sure we receive their ballot in time. industry. And as mentioned before, every vote abso- What has also grown is the voter response. lutely counts as just a few ballots determined The 2011 awards saw the biggest response some winning categories. -

ACE's Scandinavian Sojourn

ACE’s Scandinavian Sojourn : A Southerner’s Perspective Story by: Richard Bostic, assisted by Ronny Cook When I went on the ACEspana trip back in 2009, it was by far one of the most amazing vacations I have ever experienced. In addition to getting to visit parks in a different culture than we see here, it is also a great opportunity to spend time with fellow enthusiasts and grow friendships while enjoying our common interests. When Scandinavia Sojourn was announced for the summer of 2011, I knew it was a trip I could not miss. Since the 2009 trip was my first trip to Europe I thought that there was no way the over- all experience could be better in Scandinavia. I was wrong. We landed in Helsinki, Finland around 1300 the day before we were required to be at the hotel to meet with the group. Helsinki is an interesting city and fairly new compared to many cities in Europe. Walking around the city you can see the Russian influence in the city’s architecture. In fact, many movies during the cold war would use Helsinki to shoot scenes that are supposed to be set in the Soviet Union. After making our way to the Crowne Plaza Hotel and getting a quick lunch at the hotel restaurant we decided to spend the remaining time that afternoon checking out some of the sites around our hotel. Some of these sites included the Temppeliaukio Church inside of a rock formation, the train station, Routatientori Square and National Theater, and a couple of the city’s art museums. -

Summertime Is Here Corner

Coaster Con XLI Around the Corner • Parks Gear Up 2018 Rebel Yell Spring Issue The Official Newsletter of ACE Mid-Atlantic Inside This Issue Someone say airtime? Media day guests were Tempeto’s train rushes back into the station after its treated to some during a spring morning. signature and rather intense loop-the-loop maneuver. • Summertime Has Arrived • Inspiration from the Regional Rep. • Volunteer Opportunities • Prepping for Coaster Con XLI • Twisted Timbers Media Day • Losing a Coaster, Gaining Another • Winter Event at Six Flags America • Loch Ness Monster Turns 40 • A Look Around the Region • Group Photo Connect w/ Us • Questions? Feedback? Want to volunteer your time to help the region grow? Let us know by emailing us at acemidatlantic@ gmail.com or find us on social media. Upcoming Events Photo: TT Media Day, Sam Marks It’s almost summertime and the biggest event of the season is just around the Summertime Is Here corner. Join us as we celebrate coasters and New Coasters and Unexpected Surprises camaraderie at Coaster Con. See you on the midway! Are you excited for Coaster Con? We’re Dominion invited ACE members out to just about ready to kick off one of the the park for their Twisted Timbers media REGIONAL most iconic events of the summertime. day event. A month later, they invited the In less than a month, members will be region out again for a photo shoot on the Wild West Fun Day at Adventure Park - New given the chance to experience a six day new beast. The reaction to the coaster Market, MD - June 16, 2018 excursion (nine if you’re adventurous) into so far? That it’s fantastic and fits right at the best the region has to offer. -

Circular Motion Dynamics

Problem Solving Circular Motion Dynamics Problem 1: Double Star System Consider a double star system under the influence of gravitational force between the stars. Star 1 has mass m1 and star 2 has mass m2 . Assume that each star undergoes uniform circular motion about the center of mass of the system. If the stars are always a fixed distance s apart, what is the period of the orbit? Solution: Choose radial coordinates for each star with origin at center of mass. Let rˆ1 be a unit vector at Star 1 pointing radially away from the center of mass. Let rˆ2 be a unit vector at Star 2 pointing radially away from the center of mass. The force diagrams on the two stars are shown in the figure below. ! ! From Newton’s Second Law, F1 = m 1a 1 , for Star 1 in the radial direction is m m ˆ 1 2 2 r1 : "G 2 = "m1 r 1 ! . s We can solve this for r1 , m r = G 2 . 1 ! 2s 2 ! ! Newton’s Second Law, F2 = m 2a 2 , for Star 2 in the radial direction is m m ˆ 1 2 2 r2 : "G 2 = "m2 r 2 ! . s We can solve this for r2 , m r = G 1 . 2 ! 2s 2 Since s , the distance between the stars, is constant m2 m1 (m2 + m1 ) s = r + r = G + G = G 1 2 ! 2s 2! 2s 2 ! 2s 2 . Thus the angular velocity is 1 2 " (m2 + m1 ) # ! = $G 3 % & s ' and the period is then 1 2 2! # 4! 2s 3 $ T = = % & . -

Energy Storm Hits Jeju Shinhwa World

Issue 46 Jun 2018 Z Latest news from the world of amusement by ENERGY STORM HITS JEJU SHINHWA WORLD DISCOVERY’S SUCCESS ZAMPERLA RIDES SEVENTH PROJECT CONTINUES FOR WANDA GROUP WITH OCT GROUP THREE EXAMPLES OF CUSTOM DESIGNS CREATE MAJOR CHINESE GROUP ADDS POPULAR RIDE DEBUT IN 2018 UNIQUE ATTRACTIONS MORE FROM ZAMPERLA Latest news from the world of ISSUE 46 - JUNE 2018 2 amusement by Zamperla SpA Z Energy Storm hits Jeju Shinhwa World New addition joins existing Zamperla products A new customer for Zamperla in the Asia region (although previously a part of the Resort World Group) is Jeju Shinhwa World in South Korea, the theme for which is based on the experiences of the mascots of the French-South Korean computer animated TV series Oscar’s Oasis. The park first opened in the summer of 2017 and Zamperla was involved in both the first and second phases of the construction, supplying the venue with three highly themed attractions. One of these was a Magic Bikes, a popular, interactive family ride which sees participants use pedal power to make their vehicle soar into the sky. Also provided was a Disk’O Coaster, a ‘must have’ ride for every park and a best seller for Zamperla which combines thrills and speed to provide an adrenalin-filled experience. The third attraction was a Tea Cup, which incorporates triple action to create a fun and exciting experience, coupled to a high hourly capacity. And now Zamperla has also supplied an Energy Storm to the park, featuring five sweep arms which rotate upwards and flip riders upside down while also spinning. -

16 Hours Ert! 8 Meals!

Iron Rattler; photo by Tim Baldwin Switchback; photo by S. Madonna Horcher Great White; photo by Keith Kastelic LIVING LARGE IN THE LONE STAR STATE! Our three host parks boast a total of 16 coasters, including Iron Rattler at Six Flags Fiesta Texas, Switch- Photo by Tim Baldwin back at ZDT’s Amuse- ment Park and Steel Eel at SeaWorld. 16 HOURS ERT! 8 MEALS! •An ERT session that includes ALL rides at Six Flags Fiesta Texas •ACE’s annual banquet, with keynote speaker John Duffey, president and CEO, Six Flags •Midway Olympics and Rubber Ducky Regatta •Exclusive access to two Fright Fest haunted houses at Six Flags Fiesta Texas REGISTRATION Postmarked by May 27, 2017 NOT A MEMBER? JOIN TODAY! or completed online by June 5, 2017. You’ll enjoy member rates when you join today online or by mail. No registrations accepted after June 5, 2017. There is no on-site registration. Memberships in the world’s largest ride enthusiast organization start at $20. Visit aceonline.org/joinace to learn more. ACE MEMBERS $263 ACE MEMBERS 3-11 $237 SIX FLAGS SEASON PASS DISCOUNT NON-MEMBERS $329 Your valid 2017 Six Flags season pass will NON-MEMBERS 3-11 $296 save you $70 on your registration fee! REGISTER ONLINE ZDT’S EXTREME PASSES Video contest entries should be mailed Convenient, secure online registration is Attendees will receive ZDT’s Extreme to Chris Smilek, 619 Washington Cross- available at my.ACEonline.org. Passes, for unlimited access to all attrac- ing, East Stroudsburg, PA, 18301-9812, tions on Thursday, June 22. -

J-1 Visas Hang in Balance

Sept. 29 - Oct. 12, 2017 Volume 8 // Issue #20 Big Sky youth overcomes near-fatal horse accident Big Horn volleyball triumphs J-1 visas hang in balance LPHS sophomore summits Matterhorn #explorebigsky explorebigsky explorebigsky @explorebigsky ON THE COVER: Two consecutive springs, the same cow had twins behind the photographer’s cabin along the Henry’s Fork of the Snake River in eastern Idaho, about 20 miles from West Yellowstone. This photo, taken when the calves were a day or two old, was taken on May 25. PHOTO BY PATRICIA BAUCHMAN Sept. 29 – Oct. 12, 2017 Volume 8, Issue No. 20 TABLE OF CONTENTS Owned and published in Big Sky, Montana PUBLISHER Section 1: News Eric Ladd Big Sky youth overcomes EDITORIAL Opinion.............................................................................5 near-fatal horse accident MANAGING EDITOR 12 Tyler Allen Local.................................................................................7 SENIOR EDITOR Amanda Eggert Section 2: Environment, Sports, Dining & Business ASSOCIATE EDITOR Big Horn Sarah Gianelli Environment..................................................................17 EDITORIAL ASSISTANT volleyball triumphs 19 Bay Stephens Sports.............................................................................19 CREATIVE Dining.............................................................................21 LEAD DESIGNER Carie Birkmeier Business.........................................................................28 GRAPHIC DESIGNER Health.............................................................................30 -

Assignment 2 Centripetal Force & Univ

LAST NAME______________________________ FIRST NAME_____________________DATE______ CJ - Assignment 2 Centripetal Force & Universal Gravitation, 5.4 Banked Curves Draw the vectors for a free body diagram of a car in an unbanked turn and a banked turn. For this situation assume the cars are turning to the left side of the drawing. Car in Unbanked Turn Car in Banked turn Is this car in Equilibrium? Is this car in Equilibrium? Do the same for the airplane. Airplane in Unbanked Turn Airplane in Banked turn Let’s be careful to fully understand what is going on with this one. We have made an assumption in doing this for the airplane which are not valid. THE BANKED TURN- car can make it a round a turn even if friction is not present (or friction is zero). In order for this to happen the curved road must be “banked”. In a non-banked turn the centripetal force is created by the friction of the road on the tires. What creates the centripetal force in a banked turn? Imagine looking at a banked turn as shown to the right. Draw the forces that act on the car on the diagram of the car. Is the car in Equilibrium? YES , NO The car which has a mass of m is travelling at a velocity (or speed) v around a turn of radius r. How do these variables relate to optimize the banked turn. If the mass of the car is greater is a larger or smaller angle required? LARGER, SMALLER, NO CHANGE NECESSARY If the VELOCITY of the car is greater is a larger or smaller angle required? LARGER, SMALLER, NO CHANGE NECESSARY If the RADUS OF THE TURN is greater is a larger or smaller angle required? LARGER, SMALLER, NO CHANGE NECESSARY To properly show the relationship an equation must be created. -

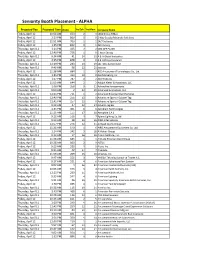

Seniority Rank with Extimated Times.Xlsx

Seniority Booth Placement ‐ ALPHA Projected Day Projected Time Order Yrs Exh Yrs Mem Company Name Friday, April 12 10:54 AM 633 2 3 1602 Group TiMax Friday, April 12 2:10 PM 860 002 Way Supply/Motorola Solutions Friday, April 12 11:51 AM 700 1 2 24/7 Software Friday, April 12 1:45 PM 832 0 1 360 Karting Thursday, April 11 3:14 PM 435 7 2 50% OFF PLUSH Friday, April 12 12:40 PM 756 105‐hour Energy Thursday, April 11 9:34 AM 41 24 10 A & A Global Industries Friday, April 12 2:25 PM 878 0 0 A.E. Jeffreys Insurance Thursday, April 11 12:29 PM 243 13 19 abc rides Switzerland Thursday, April 11 9:49 AM 58 22 25 accesso Friday, April 12 11:38 AM 684 1 3 ACE Amusement Technologies Co., Ltd. Thursday, April 11 1:46 PM 333 10 8 Ace Marketing Inc. Friday, April 12 1:07 PM 787 0 2 ADJ Products Friday, April 12 11:03 AM 644 2 2 Adolph Kiefer & Associates, LLC Thursday, April 11 2:08 PM 358 9 11 Adrenaline Amusements Thursday, April 11 9:00 AM 2 33 29 Advanced Animations, LLC Friday, April 12 12:01 PM 711 1 2 Advanced Entertainment Services Thursday, April 11 12:40 PM 256 13 0 Adventure Sports HQ Laser Tag Thursday, April 11 12:41 PM 257 13 0 Adventure Sports HQ Laser Tag Thursday, April 11 9:39 AM 47 23 24 Adventureglass Thursday, April 11 2:45 PM 401 8 8 Aerodium Technologies Thursday, April 11 11:13 AM 155 17 18 Aerophile S.A.S Friday, April 12 9:12 AM 516 4 7 Aglare Lighting Co.,ltd Thursday, April 11 9:23 AM 28 25 26 AIMS International Thursday, April 11 12:57 PM 276 12 11 Airhead Sports Group Friday, April 12 11:26 AM 670 1 6 AIRO Amusement Equipment Co. -

Santa Cruz, California, U.S.A

SANTA CRUZ, CALIFORNIA, U.S.A. Santa Cruz, California, the birthplace of mainland surfing welcomes visitors to the quintessential beach town. From old growth coastal redwood forests, to a legendary 100-year old seaside amusement park Surf’soverlooking up! the sparkling blue Monterey Bay, Santa Cruz County offers the classic California beach vacation. LOCATION wooden roller coaster that has thrilled visitors for local surfing history and overlooks Steamer Lane, Santa Cruz is approximately 70 miles/113 km south over 85 years. Seventy-three hand-carved horses one of the best places in the country to surf. of San Francisco and 349 miles/562 km north of prance proudly to the music from two beauti- Los Angeles. Many visitors choose to take scenic ful antiques: the park’s original 342- pipe Ruth STATE PARKS Highway 1 along the California coastline to Santa band organ and Wurlitzer 165 band organ at the • Santa Cruz County is home to the largest number Cruz or Highway 17 from Silicon Valley and San Jose famous Looff Carousel, built in 1911. Both the of state parks and beaches than any other county through the Santa Cruz Mountains. Visitors can Giant Dipper and the Looff Carousel are National in California - 14 in all – including California’s also choose to fly in to San Francisco International Historic Landmarks. oldest, Big Basin Redwoods State Park. Airport or Mineta-San Jose International Airport. • In the Santa Cruz Mountains, Roaring Camp • State Parks in Santa Cruz County offer visitors Railroads hosts visitors on nostalgic rides through a vast amount of diverse landscapes, from the CLIMATE the redwoods aboard vintage steam locomotives. -

Dark Rides and the Evolution of Immersive Media

Journal of Themed Experience and Attractions Studies Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 6 January 2018 Dark rides and the evolution of immersive media Joel Zika Deakin University, [email protected] Part of the Environmental Design Commons, Interactive Arts Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/jteas University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Themed Experience and Attractions Studies by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Zika, Joel (2018) "Dark rides and the evolution of immersive media," Journal of Themed Experience and Attractions Studies: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/jteas/vol1/iss1/6 Journal of Themed Experience and Attractions Studies 1.1 (2018) 54–60 Themed Experience and Attractions Academic Symposium 2018 Dark rides and the evolution of immersive media Joel Zika* Deakin University, 221 Burwood Hwy, Burwood VIC, Melbourne, 3125, Australia Abstract The dark ride is a format of immersive media that originated in the amusement parks of the USA in the early 20th century. Whilst their numbers have decreased, classic rides from the 1930s to the 70s, such as the Ghost Train and Haunted House experiences have been referenced is films, games and novels of the digital era. Although the format is well known, it is not well defined. There are no dedicated publications on the topic and its links to other media discourses are sparsely documented. -

AT Golden Ticket 1999.Pdf

Park and ride winners Page 3B AMUSEMENT 1999 Top 25 wooden TODAY roller coasters GOLDEN TICKET Page 6B AWARDS V.I.P. Top 25 steel BEST OF THE BEST! BONUS roller coasters Page 7B SECTION BONUS SECTION AUGUST 1999 1B Winners named in 2nd annual survey Amusement Today’s 1999 Golden Ticket Awards As you may recall, Amusement Today introduced a survey in 1998 to poll the well-traveled park experts and experienced enthusiasts to recog- BEST PARK BEST WOODEN COASTER nize the Best of the Best within the amusement industry. With an even CEDAR POINT larger response this year — and not to SANDUSKY, OHIO mention new parks and a mother lode of new coasters for the 1999 season — the results, as always, prove very interesting. Survey overview The poll group selected to complete the survey certainly could boast some TEXAS GIANT well-traveled experience. A greater SIX FLAGS familiarity with the North American OVER TEXAS coasters is apparent among those cho- sen, but the wood and steel coaster lists each show overseas entries. Anyone who believes a single vote doesn’t count only has to glance at the point BEST WATERPARK BEST STEEL COASTER totals to see the value of each opinion. Using various sources, selected MAGNUM XL-200 afficionados were evenly balanced by CEDAR POINT dividing the United States into four geographical regions, with an equal number of surveys sent to each region. Incidentally, all 50 states had a repre- sentative to receive a survey. An addi- tional amount of surveys were sent outside the United States to represent SCHLITTERBAHN foreign expertise.